The term “flying winemaker” generally refers to winemakers who flit back and forth between the northern and southern hemispheres so as to make wine twice a year.

Rod Phillips

Wine and Thanksgiving

So as you prepare a meal from this year’s harvest – whether of meat, fish, vegetables, grains, or fruit – complement it with an earlier year’s grape harvests.

Pinotage, South Africa’s Signature Red Wine

The name pinotage is a combination of the two grape varieties that are its parents: pinot noir and cinsault, then known in South Africa as hermitage.

All in the Wine Family: Henry of Pelham Winery

“Family” is not only evocative. It’s ubiquitous.

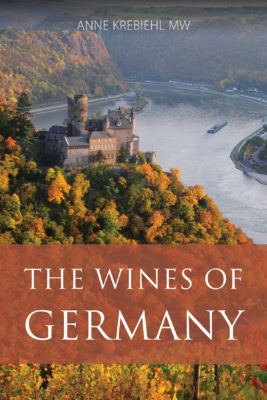

Dispelling the Myths About German Wine

Like some other wine-producing countries, Germany has had to deal with the unintended consequences of success.

The Diversity of Ontario Chardonnays

The debate about which grapes should be Ontario’s signature varieties has been going on for years.

Lambrusco: Italy’s Effervescent Red Wine

Lambrusco, the sparkling wine from northeastern Italy, is in the midst of a major makeover, and it’s high time to taste it again.

Canada’s Iconic Icewines

Icewine is ultrasweet by nature, by definition, and by law.

Pét Nat Is Coming on Strong

One of the big shifts in wine during the past two decades has been the rise in quality and popularity of sparkling wines. No doubt there’s a connection.

Corks, Screw Caps, or Other Solutions?

Corks, screw caps, and other ways of sealing bottles are referred to as closures in the wine business. But there’s no closure to the debate over the best way to seal a bottle of wine.

Pinot Gris or Pinot Grigio?

Although wines labelled pinot grigio and pinot gris are made from the same grape variety, the names generally refer to two different styles of wine.

The Weirdest Wine Policy Ever

Drink more wine, the French government urged its citizens.

What’s the Deal With Rosé Wine’s Rise in Popularity?

There’s no doubt that rosé wines have come of age. But why now?

The Lasting Inspiration of Iconic French Wines

French wines are now judged in the context of the scores of fine wines from around the world, but there is a residual belief that French wines are the benchmark against which wines should be judged.

The Complicated and Delightful Origins of Tuscan Wines

In the 1970s, for example, some leading Tuscan producers rebelled against restrictive wine laws and began to make such wines as Ornellaia, Tignanello, and Sassicaia, whose quality quickly made them more expensive than any other Italian wines.

A Q&A With Legendary Canadian Wine-grower Ann Sperling

Not only does she leave a trail of memorable and award-winning fine wines, but she also played a pioneering role in the adoption of organic and biodynamic methods.

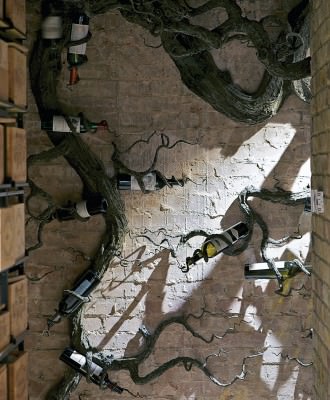

What Makes for a Destination Winery?

While many wineries tout themselves as such, true destination wineries are those that wine tourists, and sometimes wine nerds, put at the top of their must-visit lists.

The Fine Wines of Vie di Romans

One of the noteworthy wineries in Italy’s northeastern Friuli region, by the border with Slovenia, is Vie di Romans. It’s best known for its fine white wines made both from international varieties and the local friulano grape.

COVID-19 and the World of Wine

The long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wine we drink are yet to unfold, as are its effects on the economy and on everyday life.

The Many Expressions of Chenin Blanc

There are plenty of underappreciated grape varieties among the hundreds used for making the bulk of the world’s wine. One is chenin blanc, and, like many grapes, it often goes unrecognized because the wines are better known by their region of provenance than for the grape variety itself.

The Crémant Sparkling Wines of France

The current international market for sparkling wines is dominated by two styles: champagne and prosecco. But there’s one variety that deserves a lot more attention.

Négociants: The Hidden Talent Behind Many Wines

Not only does this way of making wine have a long history, but some of today’s well-known wines are made by négociants.

Monks Who Grow Wine in California: The New Clairvaux Vineyard

For many people, thinking about the distant history of wine evokes images of monks labouring in the vineyards and cellars of their monasteries.

The Renaissance of Le Clos Jordanne

The disappearance of Le Clos Jordanne wines was greeted with dismay at the time, as they were considered some of Canada’s best.

The Squeaky-clean Wines of Ca’ del Bosco’s “Berry-Spa”

At Ca’ del Bosco, owner Maurizio Zanella has given “clean wine” a new meaning: workers at the winery actually wash the grapes before pressing them.

A Wine Advent Calendar for 2019

Whether you drink them in the lead up to the holidays or during, here are our 12 wines of Christmas.

The Fabulous Future of Fizz

How do you choose when faced with champagne, cava from Spain, Prosecco or Franciacorta from Italy, sekt from Germany, Cap Classique from South Africa, and sparkling wines from England, Croatia, Chile, and hundreds of other regions?

The Last Great Gift for Wine Lovers (Besides Wine)

If the beneficiary of your giving doesn’t need glasses or an opener, there’s always a good bottle of wine… or a book.

Mouton Cadet: How One French Winemaker Survived the Great Depression

It was 1934, and the Great Depression continued to eat at jobs and prosperity. As Bordeaux’s producers flailed around looking for a solution, Baron Philippe de Rothschild found one.

These White Wines from Italy Are Seriously Underrated

Until two or three decades ago, Italian whites tended to be simple and unimpressive, but they have grown in stature and quality, the best now ranking with top contenders from around the world.

Don’t Overlook Cabernet Franc

Which type of red wine will next capture the imagination, hearts, and wallets of wine consumers?

The Case for Crown Caps: Why Some Sparkling Wine Makers Are Re-Thinking Dangerous Corks

We now know that the cork should be removed so carefully from a bottle of sparkling wine that the most you hear is a gentle hiss and that it should not become a dangerous projectile. So why seal sparkling wine with a cork at all?

What Climate Change Means for the Wine Industry

Climate change is more than just a matter of warming. Frequent episodes of heavy rain in some regions have caused erosion in vineyards.

A Statement on Wine: Martin’s Lane Winery

The Okanagan Valley has seen a recent wave of acquisitions and new investments in wineries; Martin’s Lane Winery is an impressive new build.

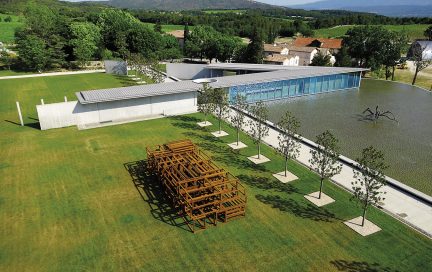

Château La Coste, France

The combination of art, architecture, and wine—white, red, and the rosé for which Provence is famous— is what makes Château La Coste different.

The Great Terroir Debate

Does the physical environment that grapevines grow in, especially the climate and soil, imprint itself the wines they make?

Super Tuscans

Once relegated to the lowly category of table wine, these blends are now internationally beloved.

Auction Napa Valley

Don’t think of a sober, sombre auction, with bidders discretely raising their paddles—this is an unabashed festive occasion.

Charity Wine Auctions

There are wine auctions, and then there are wine auctions.

A Case for Orange Wine

With no definitive way to categorize orange wine, it stands out as a distinct style.

Understanding Wine Blends and Varietals

Varieties in blended wines are like actors in movies. Some are stars, some play supporting roles, while others have cameos.

King Cabernet

Cabernet sauvignon has long been called King Cabernet and is still deserving of the title.

What Do Wine Awards Really Mean?

Many wineries love winning medals because, like high scores from wine critics, they provide external validation of their wines. But what do these accolades really mean?

A Toast to Canada

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Canada isn’t as densely planted in vines as Italy, France, and Spain, but vineyards can be found from coast to coast. To the west are wineries on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, and on the eastern seaboard are a few in Newfoundland and New Brunswick, with many more in Nova Scotia

The Rosé Renaissance

The popularity of rosé has given rise to wineries creating rosé production programs rather than treating it as a poor cousin to red and white wine.

Idiosyncrasies of Wine Labels

Whether we’re attracted to a quirky brand name or a picture of an animal, it’s the label that guides us to the bottle.

All About Chardonnay

Although some, perhaps many, wine consumers have either turned away from chardonnay completely or reduced their purchases, many more have rallied to it.

6 Unmissable Chardonnays to Try Now

From Canada to New Zealand.

Discovering Madeira Wine

Madeira, the fortified wine from the Atlantic island of the same name, is far less popular than it was a couple hundred years ago, but in the last two or three decades it’s undergone a renaissance.

A History on Malbec

Malbec has become widely known only since Argentina put it on the world wine map less than two decades ago.

Into the Loire Valley

Think of French wine regions, and the Loire Valley is not one that is top of mind.

The Wonders of Pink Wine

In the world of wine, pink might not be the new black, but quality rosé wines are on a roll. Even though pink wines will never challenge whites and reds in popularity, they are shedding their image as sweet and suitable only for people who don’t really like wine.

The Mediterranean Varieties of Paso Robles

Sometimes it’s the vegetation, not the grape vines, that tells you which wine region you’re in.

Hennessy 250

The French cognac maison celebrates its 250th anniversary with the release of Hennessy 250 Collector Blend.

Counterfeiting Quality

In March 2012, FBI agents raided the suburban Los Angeles home of wealthy wine aficionado Rudy Kurniawan and discovered a factory for counterfeiting wine.

Wine and Dynasty: Primum Familae Vini

If your Latin is rusty, Primum Familiae Vini—the alliance of Europe’s most prestigious and quality-driven family-owned wine producers—might look like First Families of Wine. In fact it means something like: First and Foremost Families of Wine.

The Wines of Long Island, New York

FROM THE ARCHIVE: New York’s best-kept secret might be a sleeper play off Broadway, a new bistro in the Meatpacking District, or a hot club in Chelsea. Or it just might be the vibrant wine region on Long Island, a two-hour drive from the city.

Rivers of Wine

It’s a cliché that the wines and food from a particular region go well together. So the high-acid reds of northern Italy complement the many tomato-based dishes common there, while pinot noir from Bourgogne pairs nicely with coq au vin. Yet the principle doesn’t always work. Marlborough sauvignon blanc with New Zealand lamb? English sparkling wine with roast beef? But if you need a poster region for this wine and food matching principle, it might well be Rías Baixas.

Belvedere Vodka

Belvedere not only rides the wave of popularity of luxury vodkas, but also makes a good claim to having established the category.

A Toast to the Ages

Wine has long been the subject of hyperbole, whether it’s Pliny the Elder’s statement that “In wine, there is truth” (in vino veritas), Jack Kerouac’s rework that “There’s wisdom in wine,” Ernest Hemingway’s assertion that “Wine is one of the most civilized things in the world,” or Michel Bettane’s more recent comment that “Fine wine is part of civilized life.”

Moët & Chandon

In the courtyard outside Moët & Chandon’s imposing premises in Épernay stands a statue of Dom Pérignon, the Benedictine monk often credited with having created champagne in the 1670s. The statue is popular with the tourists who throng Moët’s tasting room and retail store, and they stand on Dom Pérignon’s plinth to have their photographs snapped with him, as if he were a Disney character.

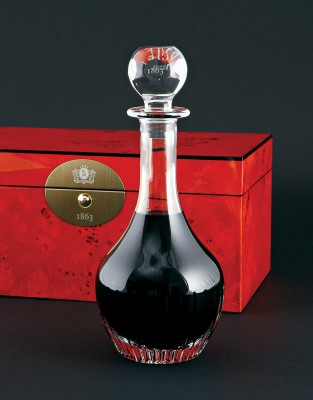

Taylor Fladgate’s 1863 Port

The grapes for Taylor Fladgate’s 1863 port were picked the year Henry Ford and William Randolph Hearst were born and the Battle of Gettysburg took place. It was a stellar year in the Douro Valley.

Vintage Revolution

A quiet revolution is taking place in Germany these days, and it might well deal with some of the major obstacles German wine has met among international consumers. The revolution is taking place in many vineyards and wineries, and in the ways that the highest-quality German wines are labelled.

Balvenie Whisky Distillery

The craft of whisky making has not changed much in the Balvenie’s production during the past century, and the distillery is one of the last in Scotland to boast in-house floor maltings that use locally hand-cut peat.

Reimagining California Wine

The common stereotypes of the wine world include the idea that all California wines are fruitbombs, high in alcohol, and full of oak. According to this image, California chardonnays are sweet, oaky, and lacking complexity or structure, and California cabernet sauvignons are intensely fruity and high-octane numbers, often with mouth-bruising tannins.

Wines of Puglia

The easiest way of locating Puglia (it’s the way it’s done there) is to say it’s the heel of the boot-shaped Italian peninsula. Wine has been made there for thousands of years.

The Wines of Tuscany

FROM THE ARCHIVE: If any landscape looks timeless—or (a more modest claim) as if it hasn’t changed for many centuries—it is Tuscany’s. But behind the landscape, Tuscany’s wine industry is anything but timeless.

Wines of Chile

Geographically, Chile counts as part of the New World, but in terms of its wine, it has a good claim to be part of the Old. Spanish missionaries and settlers planted grapevines there as early as the 1550s—and not just for sacramental purposes, by any means.

Rémy Martin’s Louis XIII Cognac

FROM THE ARCHIVE:The experience of tasting Rémy Martin’s Louis XIII Cognac—a blend of 1,200 eaux-de-vie that have been aged between 40 and 100 years—is a trip into history. A visit to Poitou-Charentes, France, reveals the soul of this precious liquid.

Preserving Wine

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Diamonds are forever, but corks are for 25 years. Well, sort of. In reality, of course, there’s no certainty about the longevity of a cork when it’s used for sealing a wine bottle; there are no actuarial tables for corks, and how long they last depends on variables like the quality of the cork and the conditions in which the bottle of wine is kept.

Armagnac

There’s just no denying that cognac is better known than Armagnac. Both are brandies, created by distilling wine, and they’re made in regions only 100 kilometres apart at their closest points. But cognac is dominated by four big brands, while Armagnac is more often artisanal.

Wines Of South Africa

The South African wine industry did not have the most impressive of beginnings. In the past two decades, South Africa’s wineries have played catch-up, and done so very successfully. Vineyards have been renovated (and expanded by more than 50 per cent), best international practices adopted, and winemaking modernized.

Le Royal Monceau, Paris

If you feel like serenading your partner in the middle of the night, or you just feel like expressing yourself musically, you’re in luck if you’re staying at Le Royal Monceau—Raffles Paris hotel.

The Penfolds Ampoule Project

The world’s most expensive bottle of wine isn’t in a bottle. It’s aging in an elongated ampoule, within a hand-blown glass vessel called a vestibule. The shape of the vestibule is a stylized form of an amphora, the pottery jar—wide at the top and tapering to a point—that was used for centuries to store and ship wine in the ancient world.

Hedonism Wines

The main course for the dinner party you’re preparing would suitably pair with a bottle of Château Cheval Blanc from 1947—widely regarded as the vintage of the century—but you don’t have one to hand. If you live in London, England, you can phone Hedonism Wines.

Layers of Luxury

Being offered a premium wine for $12 a bottle might sound a bit like being offered some prime swampland at a knock-down price. Premium has the ring of quality about it, and many people might well think of premium wines as including first-growth Bordeaux and Super Tuscans.

Argentinian Wines

If Argentines had not dramatically reduced their consumption of wine in the last few decades, the rest of the world might not be enjoying all those Argentinian wines now available in markets as diverse as Europe, Canada, the United States, and China. Fifty years ago, Argentina had one of the highest per capita rates of wine consumption anywhere.

Austrian Wines

It’s generally easy to spot an Austrian wine. The tops of most screw caps or foils show the design and colours of the country’s flag (two red bars separated by a white one), a smart move that makes Austria’s quality wines readily identifiable.

Albi, France

An hour’s drive from Toulouse in southwest France is Albi. It’s called “the Red Town” for a reason, and it has nothing to do with politics.

La Maison Hennessy

For hundreds of years, cognac was anything but a hip drink. It was always drunk straight, sometimes warmed. It was the digestif of choice for older men, who nursed snifters of the amber liquid and slumbered in massive leather armchairs after a heavy meal. So today, drinking a cognac cocktail in a tall glass with a twist of lemon seems almost heretical.

Spätburgunder

Riesling is still the single most planted grape in Germany and covers a fifth of the land planted in vines. Yet there’s been a seismic shift in the importance of other varieties, and what Germans call the “Pinot Trio” (pinot noir, pinot blanc, and pinot grigio) has made significant gains. Of these, the one to watch is pinot noir.

The A to Z of Sicilian Wine

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Sicily is one of the few wine regions where you can explore grape varieties from A to Z. You can start with ansonica and end with zibibbo—the local name for muscat of Alexandria—and, along the way, taste indigenous varieties like catarratto and nero d’Avola, and international grapes as different as syrah and sauvignon blanc.

Lost in Transplantation

There are wine competitions devoted to chardonnay and there are celebrations of zinfandel, but carmenère might be the first grape variety to have an anniversary party.

Vincent Chaperon at Dom Pérignon

At 33, Vincent Chaperon looks his age—no older, no younger. He’s smartly dressed in a suit and tie, and looks like a whiz kid in the world of law or commerce. Instead, he’s a fizz kid, the oenologist at renowned champagne house Dom Pérignon.