A Statement on Wine: Martin’s Lane Winery

An expression of design in the Okanagan Valley.

If you’re looking for a success story in the Canadian wine industry, look no further than British Columbia. The driver of B.C.’s success is the Okanagan Valley, where more than 80 per cent of the province’s wine is made. There are wineries elsewhere—in wine regions to the north and in other parts of the Mainland, as well as on Vancouver Island and some of the Gulf Islands—but the Okanagan has been the animating force from the beginning with Anthony von Mandl one of the early pioneers, never straying from his 1981 vision: “When I look out over the valley, I see world-class vinifera vineyards winding their way down the valley, numerous estate wineries, each distinctively different, charming inns, and bed-and-breakfast cottages seducing tourists from around the world.”

One sign of a maturing industry is the emergence of sub-appellations—small districts within the broader Okanagan Valley region that have gained official status for their unique combinations of climate, geology, and landscape, and the distinctive wines they produce. The first sub-appellation was Golden Mile Bench, officially recognized in 2015, and the second was Okanagan Falls, recognized in 2018. Producers in a region must make the case for a sub-appellation; others, including Naramata Bench, are expected to be approved soon. Sub-appellations speak to a maturing industry because they acknowledge a region’s growing conditions, their suitability for producing specific grape varieties, and their effects on wine style. The analogies are districts such as Pomerol and Saint-Julien in Bordeaux, or villages such as Volnay and Meursault in Burgundy, although Canadian wine laws do not impose such tight restrictions as French laws do on such matters as permitted grape varieties.

Along with sub-appellations, the Okanagan Valley has seen a recent wave of acquisitions and new investments in wineries. The prime movers in acquiring wineries have been Andrew Peller, Arterra (formerly Constellation Wines), and Anthony von Mandl, who owns iconic Mission Hill Family Estate, the go-to wine destination in the Okanagan (along with CedarCreek Estate Winery, Martin’s Lane Winery, CheckMate Artisanal Winery, and Road 13 Vineyards). New builds include the Bai family’s Phantom Creek Estates, a destination winery on the Black Sage Bench in the southern Okanagan, and Harry McWatters’ Time Winery, an urban winery in downtown Penticton.

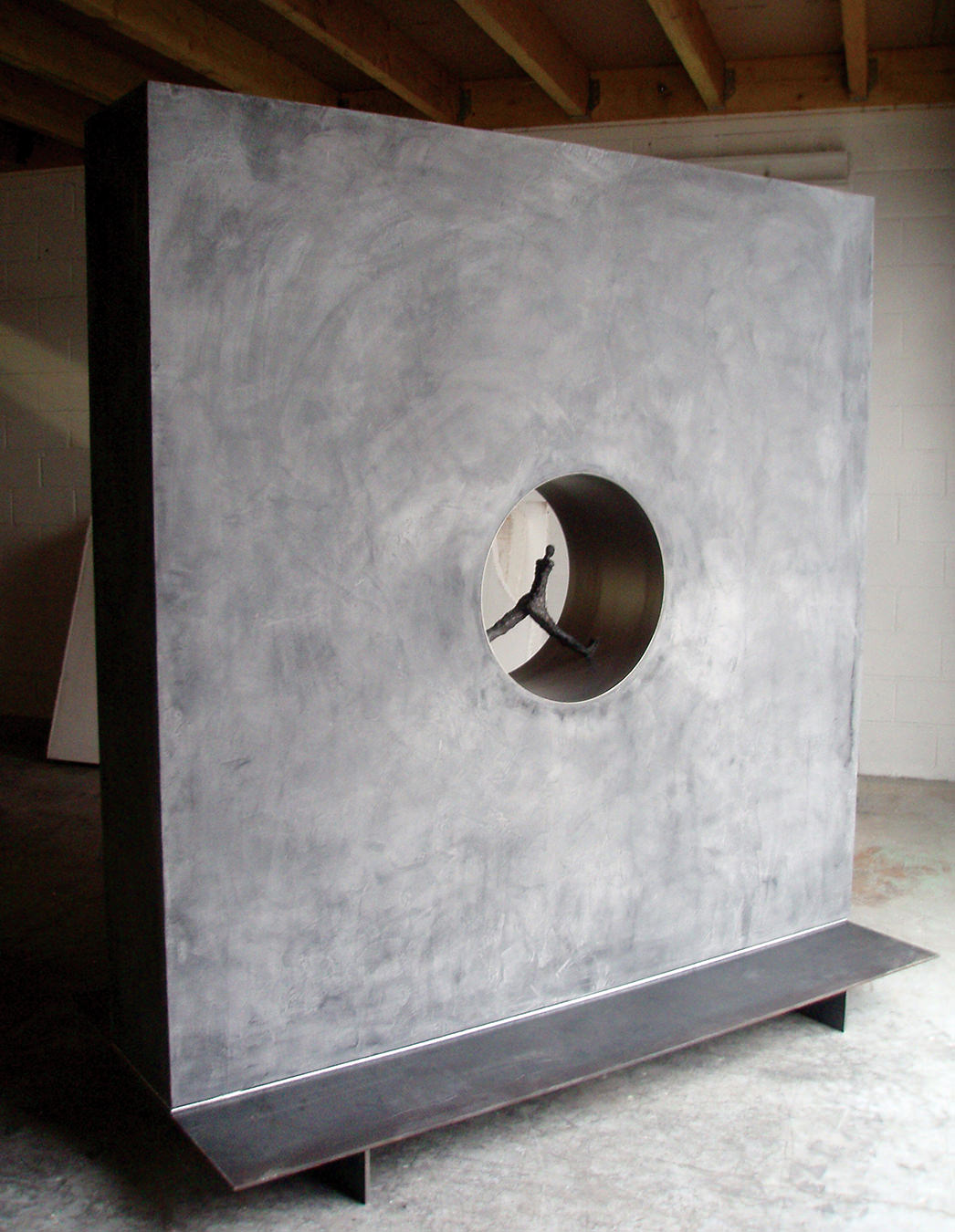

At Martin’s Lane Winery steel, concrete, wood, and glass are the order of the day, with a striking spiral staircase that rises from the main entrance.

Wine magnate Anthony von Mandl continues to transform the wine business in Canada. He has often been compared to the late Robert Mondavi. Both founded their own wineries, but actively supported their regions (the Okanagan Valley and Napa Valley, respectively), even when it meant drawing attention to their competitors. One of von Mandl’s latest creations is Martin’s Lane Winery, named for his late father. Like Mission Hill, with its arch, bell tower, and loggia echoing the Italian Renaissance, Martin’s Lane is impressive, both inside and out. But it reflects the architectural time that has elapsed in the nearly 20 years since Mission Hill was built. The same architect, Seattle-based Tom Kundig, designed Martin’s Lane and this time he produced a relentlessly modern structure that catches and holds the eye because of the tension between its two conjoined components: the winemaking structure, whose roofline follows the steep slope of the hillside, and the building that holds offices and public areas, which sits on a horizontal plane. From the tasting room in the latter, the land falls away dramatically until it ends at Okanagan Lake, giving one the impression of being in a cantilevered structure. Steel, concrete, wood, and glass are the order of the day, with a striking spiral staircase that rises from the main entrance, and some of the sombre hues and gritty textures were chosen as an homage to the massive wildfires that ripped through this area in 2003.

In the dining room, racks hold some of the most prestigious wines from around the world—a statement of the context in which von Mandl wants Martin’s Lane wines to be appreciated. The winemaker at Martin’s Lane is Shane Munn, a New Zealander who previously made wine in France, Italy, and elsewhere. He’s a proponent of intervening in winemaking as little as possible, and at Martin’s Lane he oversees a winemaking process that is gravity driven: the grapes are sorted and pressed at the building’s highest elevation point, and end up in barrels and tanks at the lowest, without the need for pumps. This is the function underlying the sloping winemaking structure.

For all its capacity, Martin’s Lane produces limited volumes of wines made from only two grape varieties: riesling and pinot noir. The grapes are drawn from three of the company’s vineyards in various locations in the Okanagan Valley and vinified separately. Each wine then is influenced by the growing conditions of the vineyard its grapes were sourced from. The four rieslings (Simes Vineyard 2015 Riesling, Naramata Ranch Vineyard 2014 Riesling, Fritzi’s Vineyard 2015 Riesling, and Fritzi’s Vineyard 2014 Riesling) range from dry to off-dry, show poised balance, round texture, and juicy acidity across the board, while the pinot noirs (Simes Vineyard 2014 Pinot Noir, Naramata Ranch Vineyard 2014 Pinot Noir, and Fritzi’s Vineyard 2014 Pino Noir) are variations on the themes of persistent fruit, well-calibrated acidity, and fine tannins. All amply show their provenance and their vintage.

Wineries such as Martin’s Lane, Phantom Creek, and Time are currently the bright, shiny objects of the modern Okanagan Valley, where the modern British Columbia wine industry began, and continues to lead the way.

For all its capacity, Martin’s Lane produces limited volumes of wines made from only two grape varieties: riesling and pinot noir.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.