Lost in Transplantation

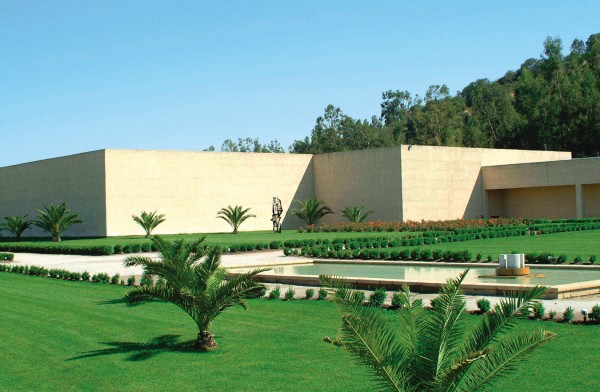

Carmenère at the Viña Carmen Winery in Chile.

There are wine competitions devoted to chardonnay and there are celebrations of zinfandel, but carmenère might be the first grape variety to have an anniversary party. And it was a party, with a red carpet, scores of distinguished guests, international media, speeches, music, an array of food—and, of course, wine.

The event, at Chile’s Viña Carmen winery, just south of Santiago, was to mark the 15th anniversary—to the day—of the discovery of carmenère in the winery’s vineyard on November 24, 1994. One of the guests was Jean-Michel Boursiquot, the French ampelographer (specialist in grape vines) who made the discovery that has transformed Chile’s wine industry.

The story of carmenère has been told before, but it’s more complicated than most of the tellings, and there are still some unanswered questions.

Carmenère was one of the red grape varieties grown in Bordeaux, and the appellation rules still include it (along with cabernet sauvignon, merlot, cabernet franc, malbec, and petit verdot) as one of the six varieties permitted in red Bordeaux wine. Thought to be related to cabernet sauvignon, it’s also known as grande vidure, while one of cabernet’s aliases is vidure. Carmenère was probably first planted in Bordeaux in the 1700s, during what’s thought of as the region’s golden age. By the mid-1800s, carmenère was frequently praised as one of the best grapes in the red blends from the Médoc region, on Bordeaux’s Left Bank, where cabernet sauvignon is now king.

Despite its popular reputation, carmenère wasn’t replanted after the infestation of phylloxera (an aphid-like pest) that wiped out vineyards throughout Bordeaux and almost all other French wine regions in the 1870s and 1880s. It’s not clear whether no carmenère vines could be found or whether a decision was made not to replant. Although carmenère was a valued addition—giving colour and flavour—to blends, it is a variety that ripens very late. In good years, it made a positive contribution, but in poor years it failed to ripen fully and must have added unwelcome green notes to some Bordeaux reds.

Whatever the reason, when the Bordeaux wine industry stood up and shook itself off after the phylloxera epidemic, there was no carmenère to be seen in the region. Yet—and this is one of the puzzles—when the rules of the Bordeaux appellation were drawn up in 1935, they included carmenère among the permitted red grape varieties.

Why would a variety that had, for all intents and purposes, disappeared more than 50 years earlier remain on the books? Perhaps someone had an inkling that carmenère would turn up somewhere; cuttings of Bordeaux vines had been sent to various parts of Europe and the wider world for experimental planting before phylloxera struck.

And, in fact, if carmenère had disappeared from Bordeaux, it hadn’t disappeared from the face of the earth. Vines had been imported by growers in Chile between 1850 and 1870, notably by Viña Carmen, established in 1850 and now Chile’s oldest continuously operating winery. (The similarity in names is coincidental;

carmenère may be named for the crimson colour—carmine, or carmin in French—of the leaves in autumn, while the winery was named for the wife of the winery’s founder.)

Carmenère is now associated with Chile as clearly as shiraz is with Australia, zinfandel is with California, and malbec is with Argentina.

In any event, carmenère survived unscathed in Chile, which is one of the few wine regions in the world that has never been affected by phylloxera. But for some reason, Viña Carmen’s carmenère vines were planted in the merlot vineyards and, over time, they became regarded as clones or variations of merlot. This is another puzzle, because there are significant differences between carmenère and merlot. The underside of carmenère leaves is reddish, while merlot’s are white. The shape of the leaves (a feature often used to distinguish one variety from another) is somewhat different. And the two varieties ripen at different times: it takes carmenère about three weeks longer than merlot to ripen.

Despite these differences, a grape variety that thrived on Bordeaux’s Left Bank was mistaken for one that thrives on the Right Bank. It seems to have been a case of scientists seeing what they expect to see: because carmenère was planted in merlot vineyards, it was thought to be merlot, regardless of the physical discrepancy between the two varieties.

The consequences of interplanting carmenère and merlot vines were not so good. Wine made from these vineyards were not really single varietals, but field blends—varietal blends that originate in the vineyards, rather than being assembled in the winery when different varieties are fermented together or (the most common method) when finished wines are blended.

In this case, the field blend of merlot and so-called red merlot didn’t work well. If the grapes were harvested when the merlot was ripe, the carmenère was unripe. But if the harvest was delayed until the carmenère was ripe, the merlot was overripe. So Chilean wines labelled merlot tended toward green or jammy.

Then came the discovery that red merlot was, in fact, carmenère. In November 1994, Jean-Michel Boursiquot, a scientist at the University of Montpellier, was attending a symposium in Santiago, and was taken to visit Viña Carmen’s vineyards. Walking among the merlot vines, he saw the red merlot with its distinctive leaves, and promptly declared that it was carmenère.

How could he identify it with such certainty? “I had seen some examples in collections in France, and also drawings,” he says, as if it’s not surprising that he should have paid such attention to a variety presumed extinct. He says it was “a chance discovery”, although he acknowledges that some Chilean viticulturists had already expressed some doubts as to whether their red merlot really was merlot.

Boursiquot’s identification of Viña Carmen’s vines as carmenère was confirmed by DNA tests and, in 1998, Chile’s Department of Agriculture officially recognized carmenère as a distinct variety in the country’s wine law. For a time, until the two varieties were replanted separately in Chile’s vineyards—a process now complete—wine labelled as merlot could include carmenère. Now, however, the two are treated as the distinct varieties they are.

More to the point, carmenère has become Chile’s signature grape variety. Although small parcels are planted in other countries, carmenère is now associated with Chile as clearly as shiraz with Australia, zinfandel with California, and malbec with Argentina. Jean-Michel Boursiquot says he’s happy to have helped transform “a simple confusion in the vineyards to a national success story.”

Cellars at Viña Carmen.

But there’s still work to be done with carmenère. Because it needs a long growing season, it has to be planted in appropriate areas of Chile’s wine regions, like the warm Colchagua Valley. And because it is, in a sense, a new variety, winemakers need to learn to work with it.

Viña Carmen’s chief winemaker, Stefano Gandolini, views it as a variety that does well on its own and can age well. Clearly, the carmenère learning curve is still on an upward trajectory. Under Gandolini, Viña Carmen is going to focus on carmenère and in some areas is extending plantings by grafting it onto existing cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc vines.

We taste a barrel sample of the 2009 Reserva Carmenère, from Colchagua Valley, and find it full of rich flavours and complexity, with a lovely mouth feel. Gandolini says this tendency toward viscosity in texture is one of the qualities of carmenère he likes. But he tries to avoid that overripeness that gives too many New World wines jammy flavours. “Overripe, and you lose the character and distinctiveness of each variety,” he says. “For me, it’s always about balance.”

Next in the glass is Viña Carmen’s 2008 Gran Reserva Carmenère, this one from the Apalta region of Colchagua, with a dash (two per cent) of cabernet sauvignon. The viscosity and the balance are evident again, and the rich, layered fruit flavours seems to embrace the acidity, giving a refreshing texture softened by sleek and supple tannins.

Then there is a barrel sample of Viña Carmen’s 2008 Winemaker’s Series Reserva Carmenère-Carignan: 80 per cent carmenère and 20 per cent carignan from 80-year-old bush vines, a blend that Gandolini calls “very exciting”. There’s a huge depth of flavour here, but it’s no simple-minded fruit bomb; the fruit is finely nuanced and well structured, and the result is an irresistible combination of power and elegance.

Carmenère, it’s clear, is a grape variety that’s experiencing a second life. From being lauded for its contribution to Bordeaux (where it is once again being planted) in the glory days, it’s now carrying the flag for Chile’s wine industry. It is starting from scratch as viticulturists figure out where to grow it and how to manage it, and as winemakers work out how to maximize its potential.

Long called “the lost grape”, carmenère is now more accurately the found grape. On its own or blended with other grapes, this varietal migrant seems ready to build on its past in Bordeaux and carve out an exciting future in its new Chilean home.