Château La Coste, France

Winery as installation.

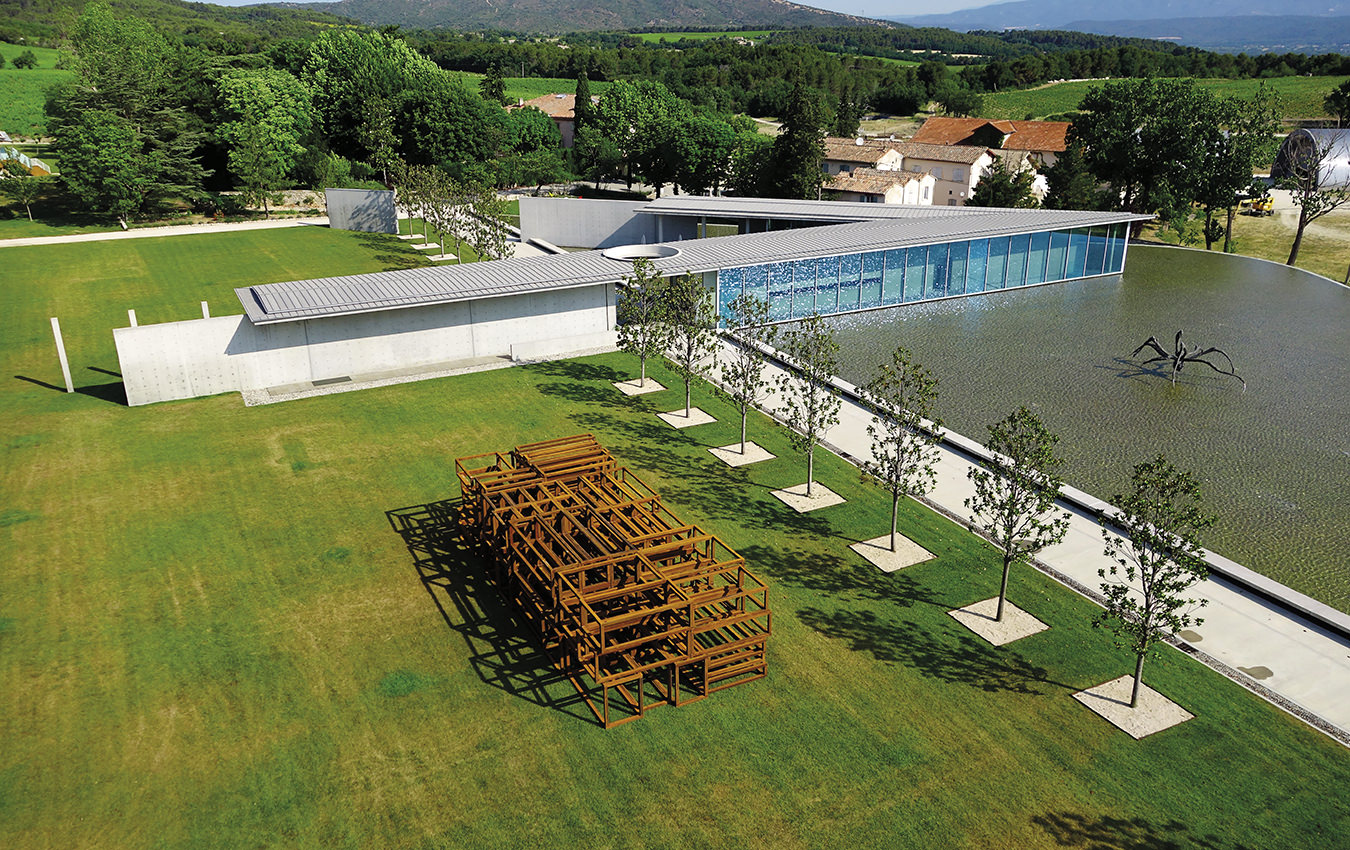

Driving between the stark concrete panels that mark the entrance to Château La Coste, a half-hour drive from Aix-en-Provence in southeast France, you’re struck by an apparent contradiction in the architecture. Ahead lies the expanse of an infinity pool and a sleek, low-lying building of concrete and glass that houses the winery’s welcome centre, restaurant, and bookstore. Yet to the right, across a vineyard, lie what appear at first glance to be two outsized Nissen huts, the prefabricated, semicylindrical, corrugated-metal structures widely used by the military as warehouses during the Second World War.

But these are stainless steel and aluminum structures designed by noted French architect Jean Nouvel. Their smooth, shiny surfaces reflect the Provençal sun; these shells house one of the most modern winemaking facilities in France. As for the hospitality building, designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando, it is as far from most people’s image of a French château as Japan is from Provence.

A close up of Louise Bourgeois’s Crouching Spider, 2003. ©Louise Bourgeois Foundation. Photo via ADAGP Paris, ©Andrew Pattman, 2016.

Ando, who says he was inspired by Paul Cézanne (who worked in the region around Aix-en-Provence), designed the building with geometrical flair. The angles and edges fit seamlessly into the softer contours of the land. The light for which this part of France is famous is allowed generous access to the building through a series of spaces and skylights. The shallow pool, which doubles as the roof of a parking garage, is partly occupied by Crouching Spider, a massive and slightly menacing bronze piece by French-American artist Louise Bourgeois that seems to guard the building.

The combination of architecture, art, and wine is what makes Château La Coste different. It’s the brainchild of Patrick McKillen, a developer from Northern Ireland who besides owning office buildings, shopping centres, and five-star hotels in a number of countries is also a serious art collector. McKillen bought Château La Coste in 2002 and began to rebuild the winery from the ground up—and from the surface down, if you think of the new cellars. He also imagined it being enriched by the work of architects and artists, established and new, from around the world.

Virtually all that remains of the original estate is the 17th century bastide, a Provençal country house (this one designed in an Italianate style), and a hillside chapel that dates from around the same period. The bastide sits on its own grounds, set off from the modernity of the structures around it. But the chapel has been transformed into an installation by being encased in a glass-and-steel protective cage designed by Ando.

Beginning in 2004, McKillen invited artists to visit the property, walk the grounds, and imagine a work of art in a location that spoke to them. To date, the result is 32 installations augmenting several hectares. The highly eclectic collection represents a wide range of genres, materials, and statements; it is a corpus only in the sense that the works are gathered together in one delimited space. As disciplined or undisciplined as the style of each piece might be, the collection itself is disordered and untamed, and it is in this sense that it is integrated so well into its environment. As orderly as Château La Coste’s vineyards are, the rest of the estate is essentially wild, an uneven and hilly terrain of grasses, bushes, and trees.

The combination of architecture, art, and wine is what makes Château La Coste different.

That environment changes seasonally, giving the installations an ever-evolving backdrop. Some stand out vividly in all seasons. One is Multiplied Resistance Screened by Liam Gillick. This is a set of movable metal panels in bright orange, blue, red, green, and purple. Among the pieces that are less easily visible is Foxes by Michael Stipe, the former lead singer of R.E.M., who reinvented himself as a visual artist. The seven bronze foxes blend effectively into their habitat in the earth tones that dominate during the autumn and winter, but come more into relief during the summer.

The winemaking facilities designed by Jean Nouvel. Photo via ©Andrew Pattman, 2016.

Although most of the works are meant to be viewed passively, some are intended to be manipulated and used. Frank Gehry’s Music Pavilion is a wood-and-glass structure anchored on four massive steel columns that can be used for intimate performances or other events. The American artist Larry Neufeld contributed two stone bridges (titled Donegal) that ford a small stream. Their perfect semicircular arches echo the semicylindrical shape of Nouvel’s winery structures.

Several works follow a wine theme. The Irish artist Guggi created a massive bronze cup, called Calix Meus Inebrians—it’s a reference to the Biblical text “My cup runneth over,” which can also be rendered “My cup makes me drunk.” It’s situated, very appropriately, at the edge of one of Château La Coste’s vineyards.

A subtler reference to wine is Oak Room by the British artist Andy Goldsworthy, built into a hillside and lined with interlaced oak branches, stripped of their bark and bent to form the shape of an inverted bird’s nest. Steps lead into the room as they would into a winery cellar where oak barrels hold wine as it ages. A barrel is the centrepiece of yet another installation: British one-time shock artist Tracey Emin’s Self Portrait: Cat in a Barrel. Visitors tread a narrow walkway (catwalk?) to a platform and peer through the bunghole of a barrel to see the ceramic cat inside.

These are reminders that we are at a winery, not simply in an art park. The vineyards, replanted in the 1960s, have been organic since 2009 and are aiming for biodynamic designation. Château La Coste makes wines in white, red, and the rosé for which Provence is famous—although only 60 per cent of its wines are rosé, compared to 80 per cent in the general region. Not surprisingly, half of Château La Coste’s wines are sold in France, where there’s a great thirst for rosés.

The interior of Frank O. Gehry’s Pavillon de Musique, 2008. ©Gehry Partners et Château La Coste, 2016. Photo via © Andrew Pattman, 2016.

One of La Coste’s rosés is a sparkling wine, made using the Champagne method from grenache and cinsault. It’s very pale pink (the colour known as oeil de perdrix, partridge eye) and delivers bright flavours, vibrant acidity, and plenty of fine bubble activity. Among the still rosés, two are noteworthy: Rosé d’une Nuit, which is mostly grenache with syrah and cinsault playing supporting roles. Understated in colour, it’s also fairly understated in flavour but nicely complex and very clean. As for Grand Vin Rosé, it’s the palest of pinks without being white, but the fruit is well defined and the acidity fresh and vibrant.

Visitors to Château La Coste are invited to stroll gravel paths and discover the art.

This focus on rosé should not obscure the whites and reds. Les Pentes Douces Blanc, a reference to the gentle slopes of the property, is a vermentino and sauvignon blanc blend. It has beautiful balance, with the sauvignon throwing acid in support of the vermentino fruit. The Grand Vin Blanc also uses mostly vermentino, but with chardonnay this time, the grapes drawn from 45-year-old vines. The Grand Vin Rouge 2012, a cabernet sauvignon–dominant blend with grenache and syrah, is harmonious and delicious, with plenty of rich, complex fruit and excellent balance. But the heavy-hitter is the Grande Cuvée 2012, half cabernet sauvignon and half syrah. It’s robust and full of well-structured fruit, but with astringency and tannic grip that demand a few years’ cellaring.

Visitors to Château La Coste are invited to stroll gravel paths and discover the art. If walking through the hectares of art works up an appetite, Le restaurant de Tadao Ando is named for its designer, a notable exception to naming an establishment for its chef, but a fitting recognition of his extensive contributions to Château La Coste. The winery also makes a vin cuit, or “cooked wine,” the result of boiling grape juice to reduce its volume before allowing it to ferment. It’s a style of wine that has deep roots in Provence, and it delivers some sweetness along with delicate oxidative notes reminiscent of some sherries.

Château La Coste’s art colony is a work-in-progress. Each year, pieces are added to those that already populate the estate. Artists who are now invited have to think of a work that fits the contours of the land, the particular exposure to the sun, and the existing flora. But as the density of the collection increases, each new artist will also have to consider how their work will relate to other works that have preceded it.

Tom Shannon’s Drop, 2009. ©Tom Shannon, 2016. Photo via ©Andrew Pattman, 2016.