-

Francesca Amfitheatrof.

-

Francesca Amfitheatrof.

-

Tiffany T Square ring in 18-karat rose gold and bracelet in sterling silver. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

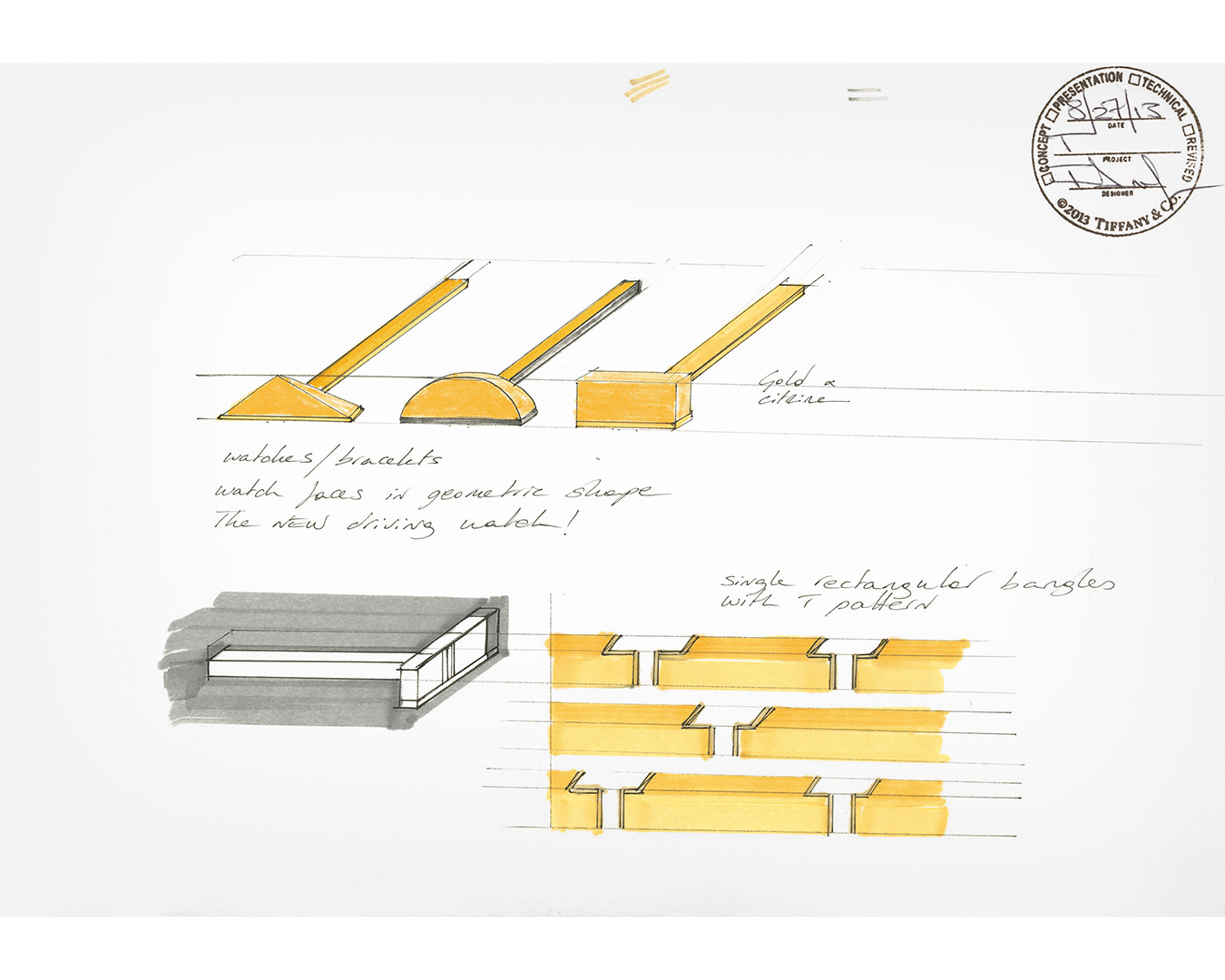

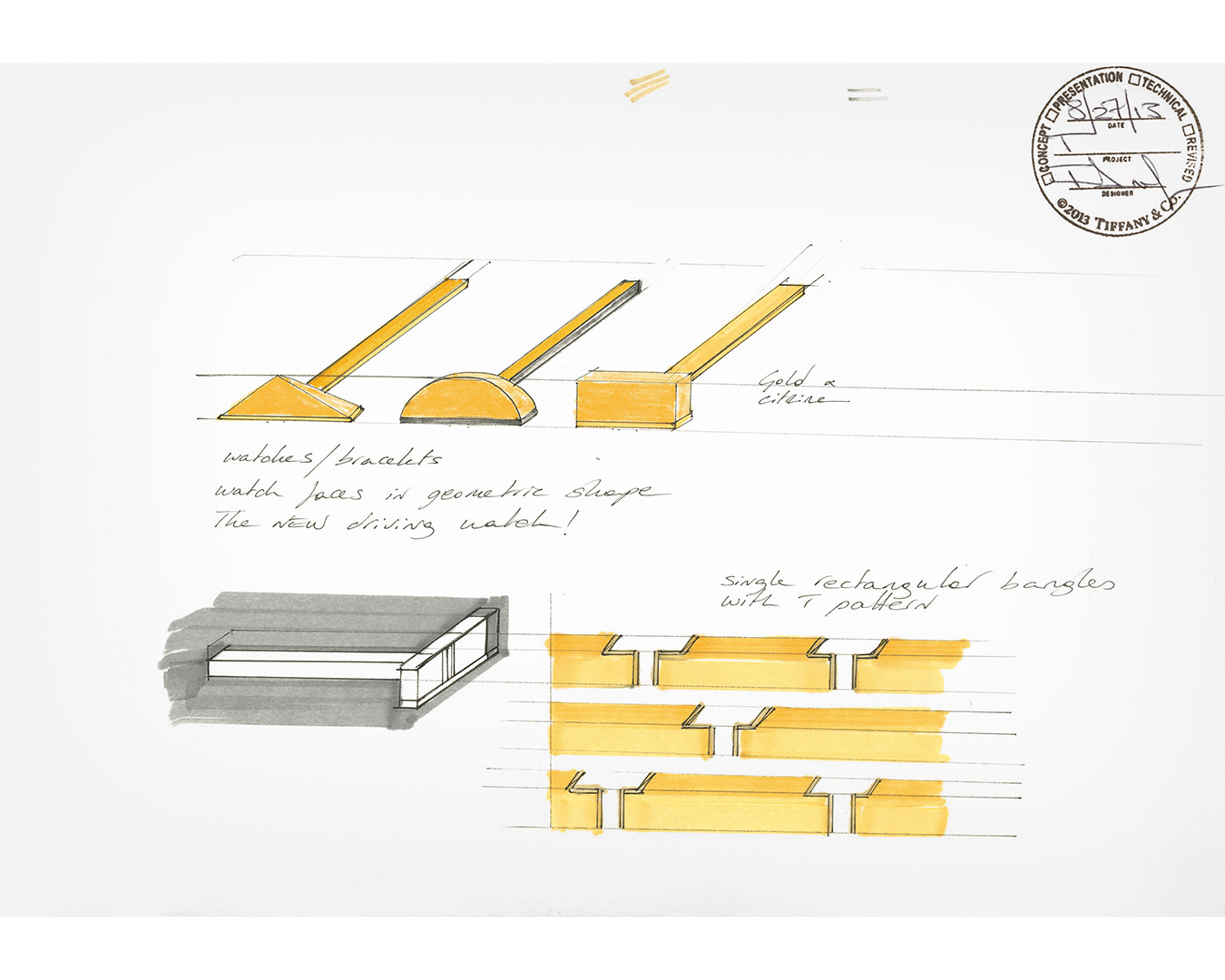

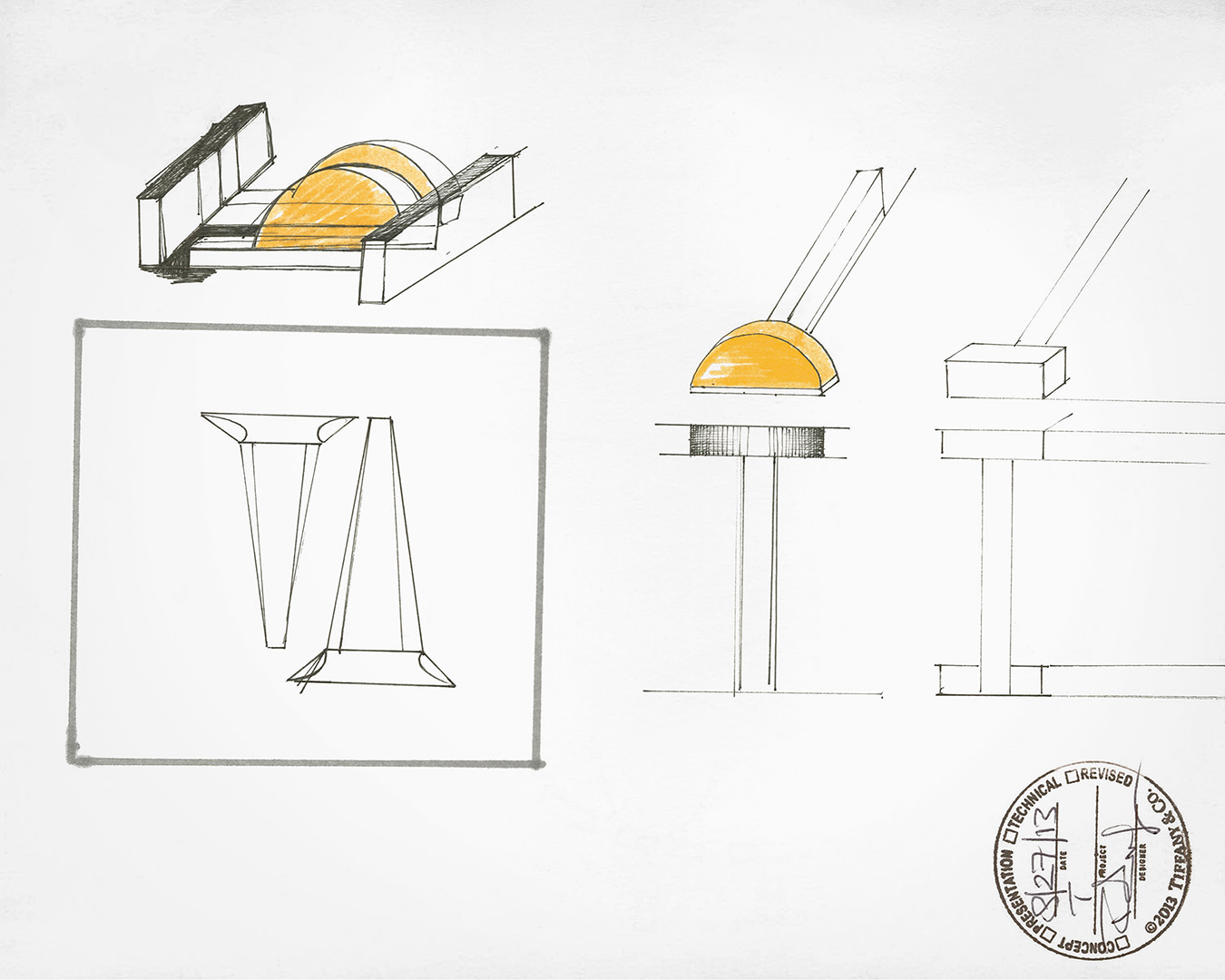

Sketches for the Tiffany T collection by Francesca Amfitheatrof. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

Tiffany T Square bracelet in 18-karat yellow gold. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

Tiffany T Square rings (from top): 18 karat-rose gold; sterling silver; 18 karat-yellow gold. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

Francesca Amfitheatrof’s designs for the Tiffany T collection. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

Tiffany T (from left): Square bracelet in 18-karat yellow gold; cut-out cuff in 18-karat yellow gold with white ceramic; large chain bracelet in 18-karat yellow gold. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

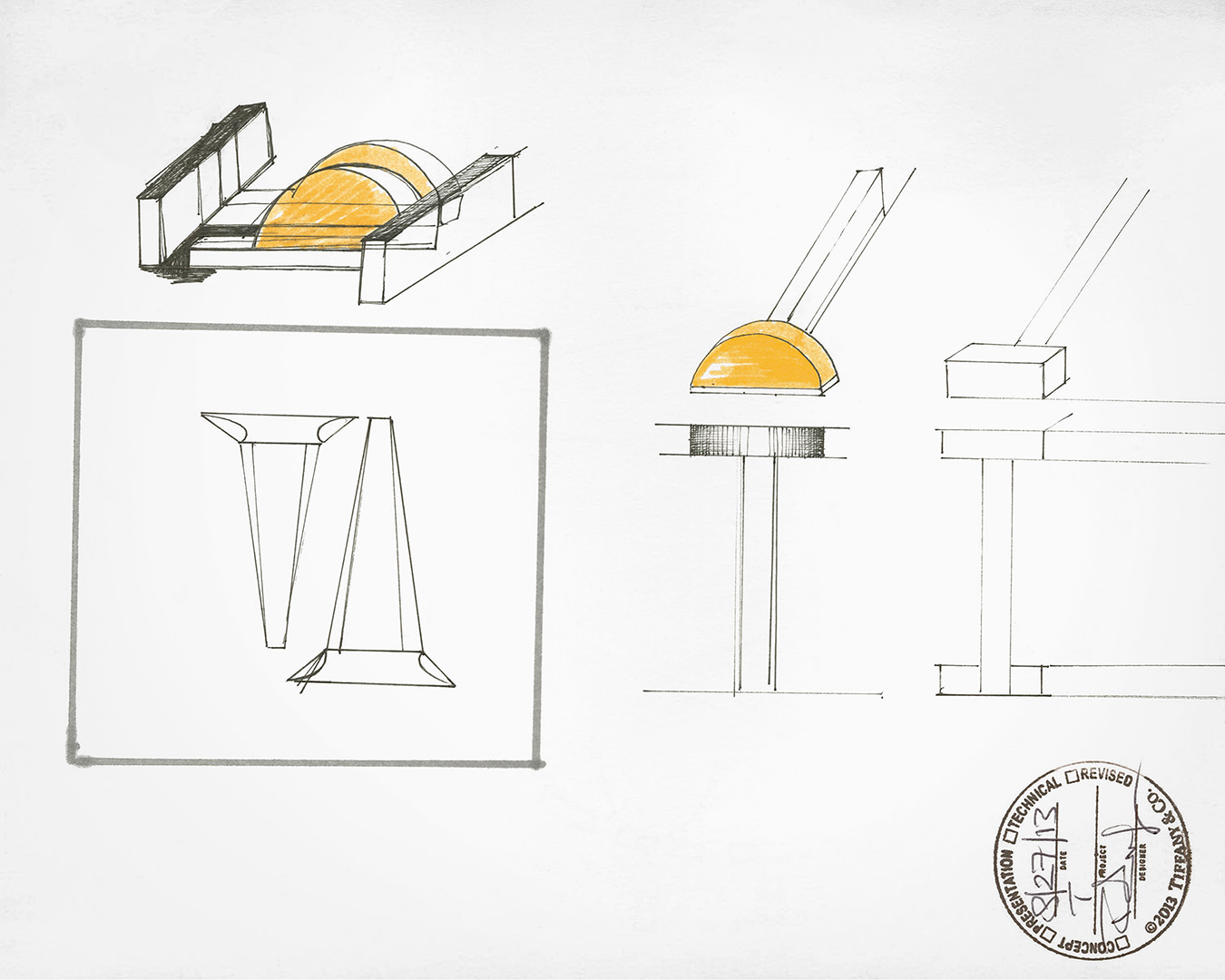

Sketches by Francesca Amfitheatrof for the Tiffany T collection. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

-

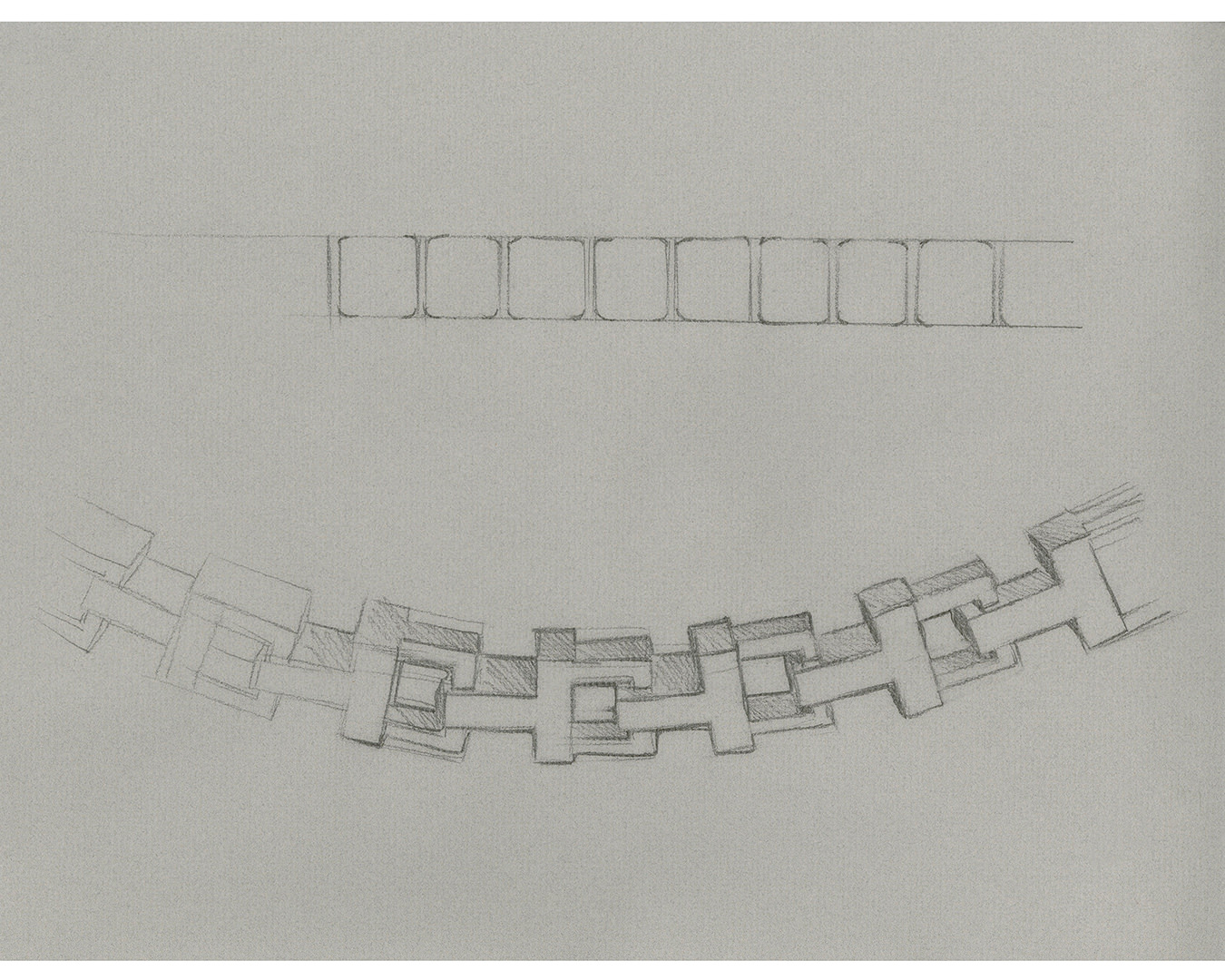

A sketch for the Tiffany T collection. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

Francesca Amfitheatrof

Lady of the house.

Francesca Amfitheatrof was studying for her master’s degree at London’s Royal College of Art when she participated in one of those classic art school exercises: “You’d be in a studio,” she recalls. “They would blindfold you and there would be a very large piece of paper at the end of the wall and they’d say, you’re going to walk to the wall and you’re going to leave your mark and whatever that mark is, is you.”

To anyone who knows Tiffany & Co.’s dynamic new design director—the first woman to hold the title in the venerable retailer’s 177-year history—it should come as no surprise that Amfitheatrof’s instinct was to make a bold, graphic statement.

Tiffany T Square ring in 18-karat rose gold and bracelet in sterling silver. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

“My mark was very energetic,” says the forty-something designer in a crisp British accent. “It was a sort of Twombly mark.” More than two decades on, Amfitheatrof says the art school episode still resonates with her. “Exercises that try to get rid of any weight on your shoulders of what is expected of you—I think they’re great,” she says. “They let you be very creative by allowing myriad possibilities.”

Amfitheatrof may as well be talking about her new role at Tiffany & Co. When she moved her family—her venture capitalist husband, Ben Curwin, and their two children—from London to New York last year to join the ranks of North America’s premier luxury jeweller, the company had been operating without a design director for four years. Her predecessor, John Loring, retired in 2009, leaving behind what most people familiar with his legacy would describe as enormous shoes to fill. An accomplished author and art professor, Loring spent 30 years at Tiffany, helping build the company from a small business of six stores, all located domestically, into a global luxury brand with $4-billion (U.S.) in net sales for its last fiscal year.

“John was a magician,” says Judith Price, president of the National Jewelry Institute and a long time acquaintance of Loring’s. “But not everyone can create magic. It’s like a dream. That’s why John’s job is not a job. It’s lightning.”

Sketches for the Tiffany T collection by Francesca Amfitheatrof. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

Two points should quell the skeptics. The first is Amfitheatrof’s freshman undertaking for Tiffany & Co., this season’s Tiffany T, a bold, architectural collection that marries a fresh, modernist aesthetic with retro 1940s futurism. The second is her impressive curriculum vitae, a densely packed and improbably diverse account of a career that’s strayed far from the beaten path. In some respects, you might say Amfitheatrof has been preparing for the Tiffany & Co. role all her life. Born in Tokyo to an Italian fashion publicist mother, who worked for the likes of Valentino and Armani, and an American journalist father, Amfitheatrof spent her childhood in Snedens Landing, N.Y., across the Hudson River from Manhattan. “My father was a bureau chief at Time, so every four years we moved somewhere else,” she says. “But my first memories are of New York. It feels really familiar to me.”

Well-spoken and poised, Amfitheatrof exudes a worldly sense of sophistication whose roots, it’s easy to imagine, lie in an extraordinarily peripatetic childhood. From kindergarten in New York to grade school in Italy to boarding school in England—where she waited out her father’s term as Time’s Moscow bureau chief at the height of the Brezhnev era—she spent her formative years shuttling around the world, getting her first taste of the international art and design scene that would feed her imagination later in life.

At boarding school in the U.K., an art teacher who dared her students to reach beyond the limits of a basic O-level education inspired Amfitheatrof to explore her artistic side. An early school project in which the budding designer hand-carved a silver hair ornament and an ebony stick to hold it in place when worn marked a turning point in her life. “I made the piece in silver and I set stones, which is quite ambitious as your first piece of jewellery—and I loved it from that moment on,” she says.

Once the proverbial spark was lit, Amfitheatrof fanned the flames with a foundational art course at the Chelsea College of Arts, where she studied a broad mix of subjects: painting, sculpture, textiles, printmaking, fashion, 3-D design, industrial design, and graphic design. When it came time to narrow things down, her unequivocal choice was jewellery.

“It’s quite strange to know what you want to do that young,” she says. “You’re sort of goofy, you don’t quite know what you want to do in life—but I knew.”

The seven years of art training that followed—beginning with a BA in jewellery design at London’s Central Saint Martins and concluding at the Royal College of Art—left Amfitheatrof with the conviction that her riches would not lie in the niches. (Upon graduating college, Amfitheatrof was designing functional objects for Alessi. “I started with a fruit bowl, then did a toothbrush holder, soap dish, key ring … That was ongoing, continuously happening.”)

“I always wanted to do everything,” she recalls. “I already wanted to work at Tiffany. I wanted to work at fashion houses. I wanted to do my own line. I wanted to collaborate. The way my character is—I take on things in a very big way. Even when I design, I don’t design one piece of jewellery, I design massive collections. I tend to think quite big about things.”

Amfitheatrof’s considerable appetite for life experiences was borne out in a decision she made upon graduation in 1993. “Most people that emerge from the Royal College of Art are pretty much given a grant by the Crafts Council and a workshop and they will give you enough money to buy tools and rent and keep you going for about a year—and I couldn’t think of anything worse,” Amfitheatrof says. “The idea of ending up in a workshop on my own, making one piece of jewellery here and one piece of jewellery there for clients and friends. I thought—that’s just not me.”

“I’m very interested in volume and shape and texture and patinas. I’m less of a decorative jeweller. I’m very much into proportions and the feeling of a piece on your skin.”

Instead, she escaped to Veneto, the heart of Italian gold country, where she apprenticed with a master craftsman who taught her how to alloy her own gold and handcraft objects in silver.

“You start with a silver disc, like a CD, and you hammer ’round over a tool, and every time the metal hardens, you anneal it again by reheating it,” Amfitheatrof says. “It’s one of the most antiquated and anachronistic ways to lift a pot; most people would spin it on a machine, on a lathe, but I liked to learn the old way.”

Amfitheatrof’s Italian mentor taught her the value of expediency and the dangers of wasting metal—two lessons about working with jewellery that art school conspicuously failed to impress upon its students. “He would say to me, ‘You have two days to make a ring,’” says Amfitheatrof. “At art school, you don’t learn about speed. You’re a bit useless. You waste too much metal. Jewellers are very paranoid about weights of gold and silver and he taught me all of that.”

Equipped with the knowledge she needed to excel in the real world, Amfitheatrof returned to London and scored a show—her first—at the legendary White Cube gallery, owned by her friend, Jay Jopling. Her raised vases and gold and silver jewels were a hit with the fashion crowd, including Karl Lagerfeld, who bought a slew of pots for his home. The exposure propelled her into a thriving wholesale career that found her selling her jewellery to stores as far away as Japan and Australia; Colette in Paris was a faithful customer. The show was more than just a successful marketing vehicle, however: it affirmed the pure, modernist style Amfitheatrof had been cultivating since art school.

“I knew then, exactly, who I was going to be,” she says. “I’m very interested in volume and shape and texture and patinas. I’m less of a decorative jeweller. I’m very much into proportions and the feeling of a piece on your skin. I’d say there’s a lightness to my jewellery, and there’s something that maybe is a little bit Oriental, like when you look at beautiful Korean pots, or when you look at [artifacts by] the Japanese: the purity of a form. That’s what I really love.” Amfitheatrof nurtured her fascination with the East during this time, when she began travelling, to Jaipur in the Indian state of Rajasthan to buy gemstones and then skipping to Bangkok to oversee the production of her jewels. “I worked out this great way to make my life as adventurous as when I was a kid,” she says.

Tiffany T Square rings (from top): 18 karat-rose gold; sterling silver; 18 karat-yellow gold. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

It wasn’t long, however, before Alice Temperley, Chanel, and Fendi all commissioned catwalk pieces. When the British royal jeweller Asprey & Garrard asked Amfitheatrof to join the heritage brand as head designer in 2001, she decided it was the right time to give up her independence. She was there a year later when the house split, and stayed on for an additional year as head designer for Garrard. From there, Amfitheatrof did something unexpected (unless you know her, in which case it was entirely expected): she designed an eyewear collection for Marni.

“I’d never done eyewear before, but it really doesn’t matter—I always want to do everything,” she says. “I don’t think it’s naive. You just throw yourself in there. If you can design a piece of jewellery, you can design eyewear—why not?”

Amfitheatrof parlayed her eyewear experiment into designing jewellery and accessories for Marni. But she didn’t confine herself to the world of fashion. In 2001, Amfitheatrof and two partners established RS&A, a London-based agency that financed the production of conceptual art shows, such as when they asked five artists—Damien Hirst, Paul McCarthy, Yayoi Kusama, Jake and Dinos Chapman, and Maurizio Cattelan—to make chess sets. They displayed the sizable art works at London’s Somerset House alongside historic chess sets, including ones made by Fabergé and Alexander Calder.

The work found Amfitheatrof completely in her element. “I’ve always been around artists, always been very connected to artists,” she says. “I was very lucky because in the nineties I was around all the White Cube [personalities]. I saw the evolution of that. It was part of my life.”

Living, today, in Brooklyn, Amfitheatrof commutes to Tiffany & Co.’s global headquarters in Manhattan’s fashionable Flatiron District, where the swirl of art and industry surround her. From her eleventh-floor design studio—an airy, light-filled space stocked with jewellery sketches, design tools, and shelves upon shelves of books (sample tomes: Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature, Nicholas Foulkes’s Swans: Legends of the Jet Society, and just about every conceivable Tiffany publication)—she commands a team of 23 designers who are helping her write the next chapter in the retailer’s storied tale of American craftsmanship.

Sketches by Francesca Amfitheatrof for the Tiffany T collection. Photo ©Tiffany & Co.

The role has been a long time in coming. Amfitheatrof dates her interest in the house to her childhood discovery of Loring’s 1981 coffee-table book, The New Tiffany Table Settings (co-authored with Henry B. Platt), whose pages showed a whimsical assortment of table set-ups imagined by contemporary artists and celebrities: Andy Warhol’s jailhouse dinner, for example. As she grew more familiar with the brand, however, she fell in love with the iconic work of one of its most famous collaborators.

“Elsa Peretti is a god,” she says. “For any young jeweller, she is the ultimate designer. She changed the way we wear silver, and anything she designs is still completely relevant and fresh. The attraction towards Tiffany was linked very much with her and her designs.”

But make no mistake: Amfitheatrof’s stamp on Tiffany T, like that “Twombly mark” she made back in grad school, is very much her own. A singular reflection of her life’s preoccupations—art, fashion, travel—the sculptural collection comprises stylish and technically complex gold chains, wide gold cuffs (including a set of handcuffs inspired by Harry Houdini, a Tiffany & Co. client), stacking rings, and geometric necklaces set with opaque stones like carnelian and chalcedony. Unlike so many of Tiffany & Co.’s diamond-studded Deco lines, T riffs heavily on the machine-age aesthetic associated with New York City in the 1940s.

“The collection feels fresh and I think it will surprise people,” says Jill Newman, a seasoned jewellery writer in New York. “It’s not the classical mould.” And that’s precisely the point. Of Tiffany T, Amfitheatrof says, “It’s really talking to contemporary women who are urban citizens,” and she cites the archetypal New York woman as a prime design inspiration. “There’s something about New York women that has a symbolic meaning. They’re not passively waiting for things to happen to them. They are making things happen.”

Tiffany’s maverick new design director chief among them.