-

Inside the office of Richard Meier & Partners Architects in New York.

-

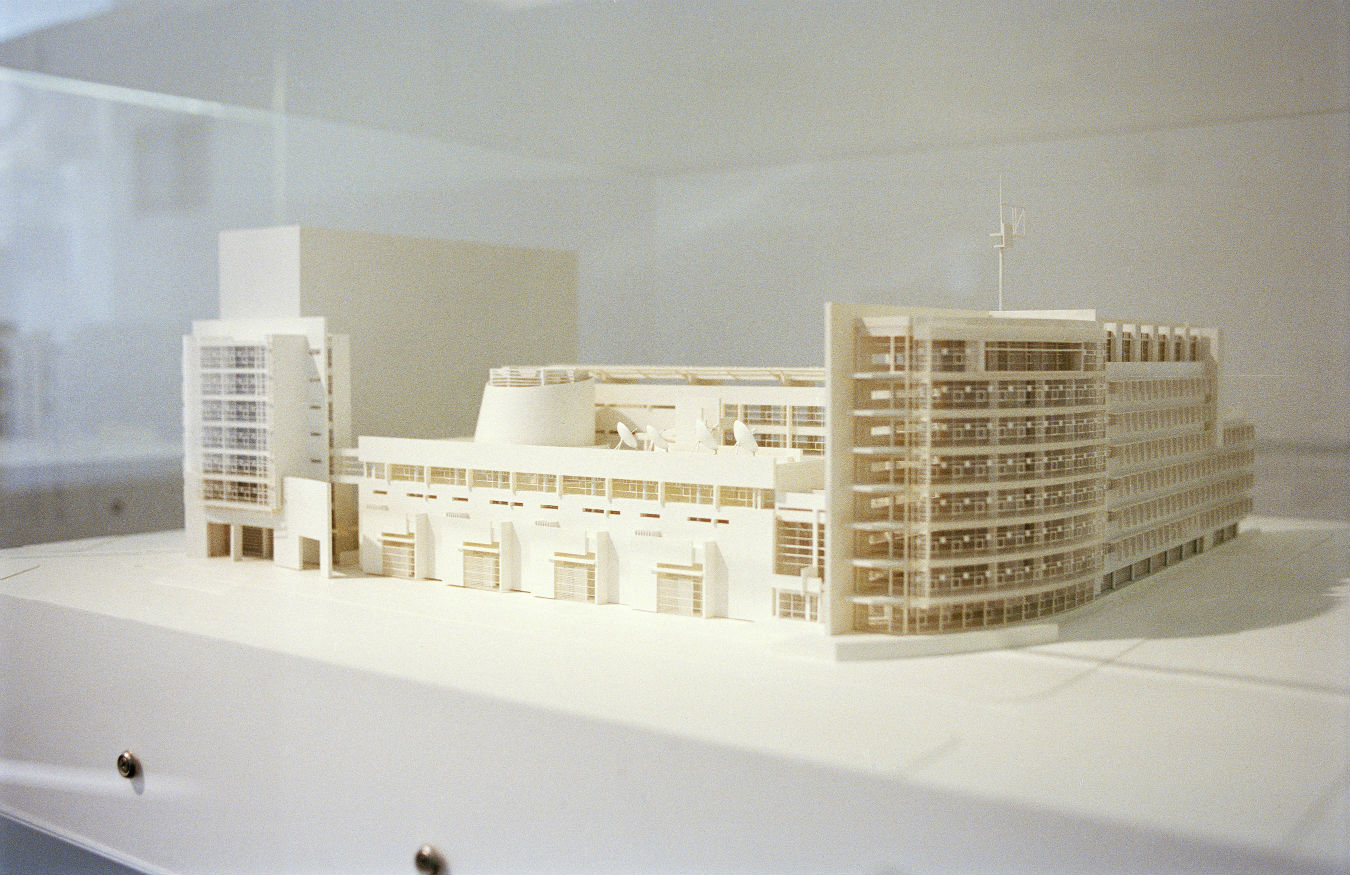

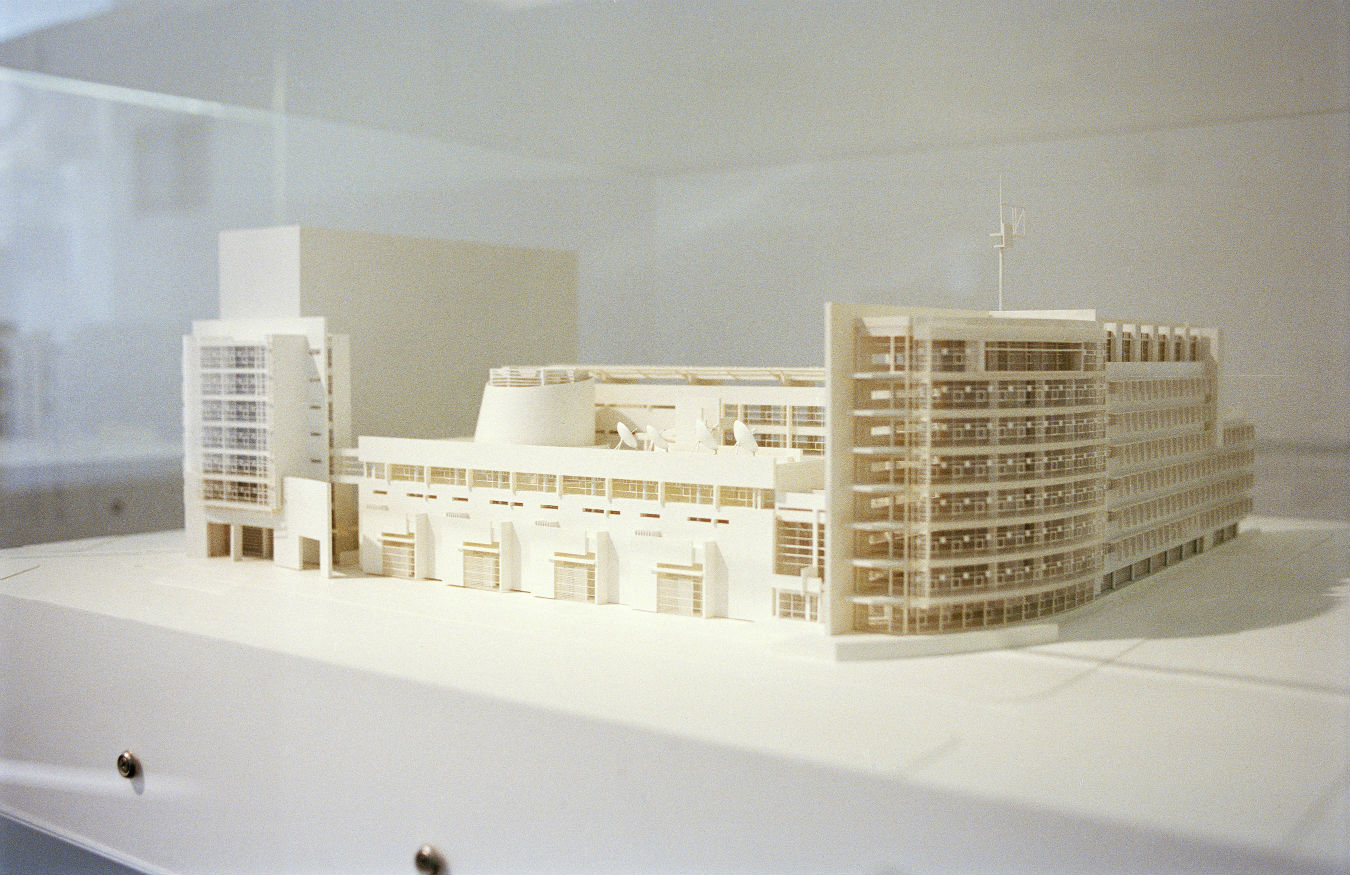

A model for the Canal+ Headquarters in Paris, France, 1988–1992.

-

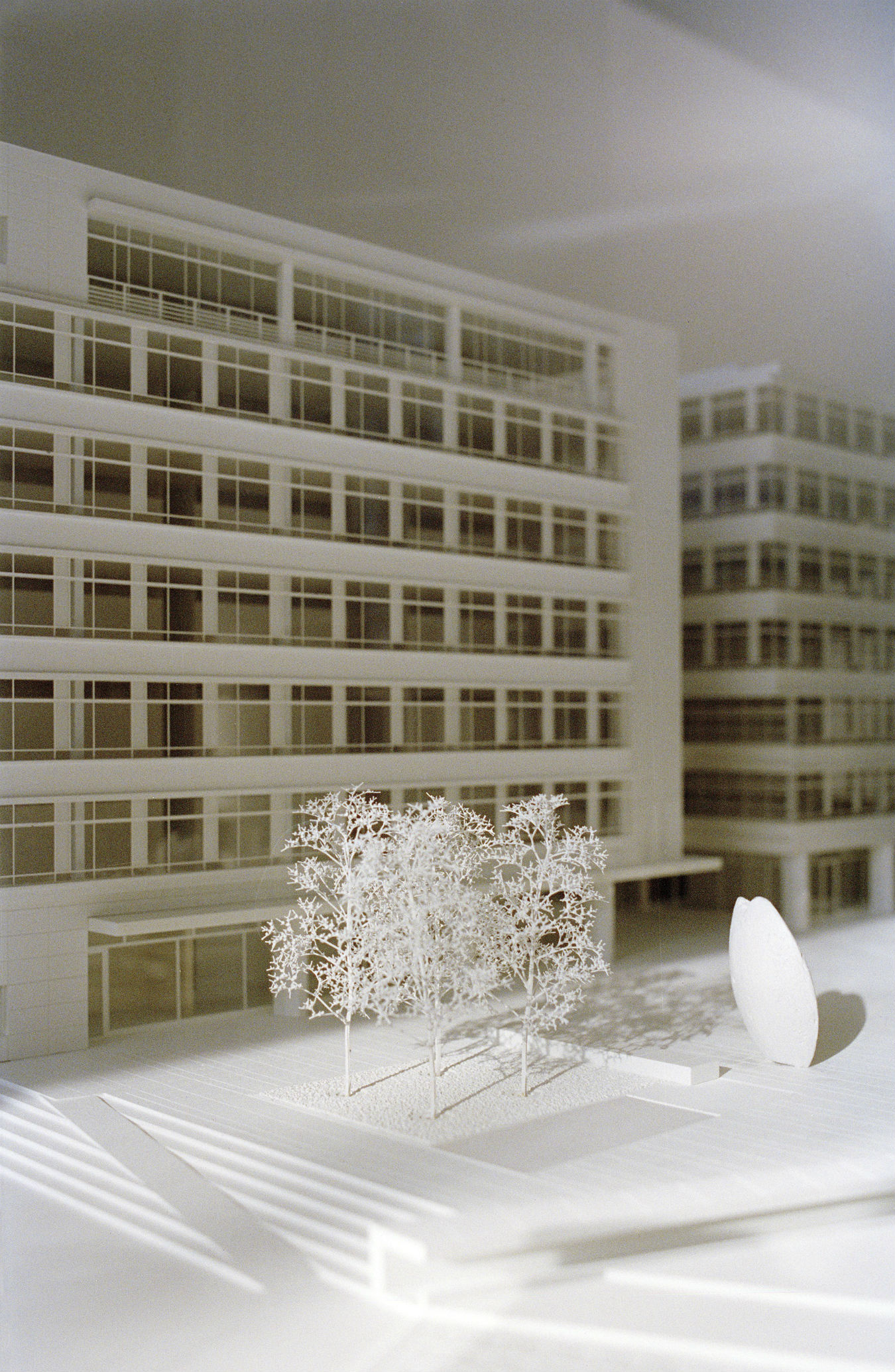

A model for the Coffee Plaza in Hamburg, Germany, 2004–2010.

-

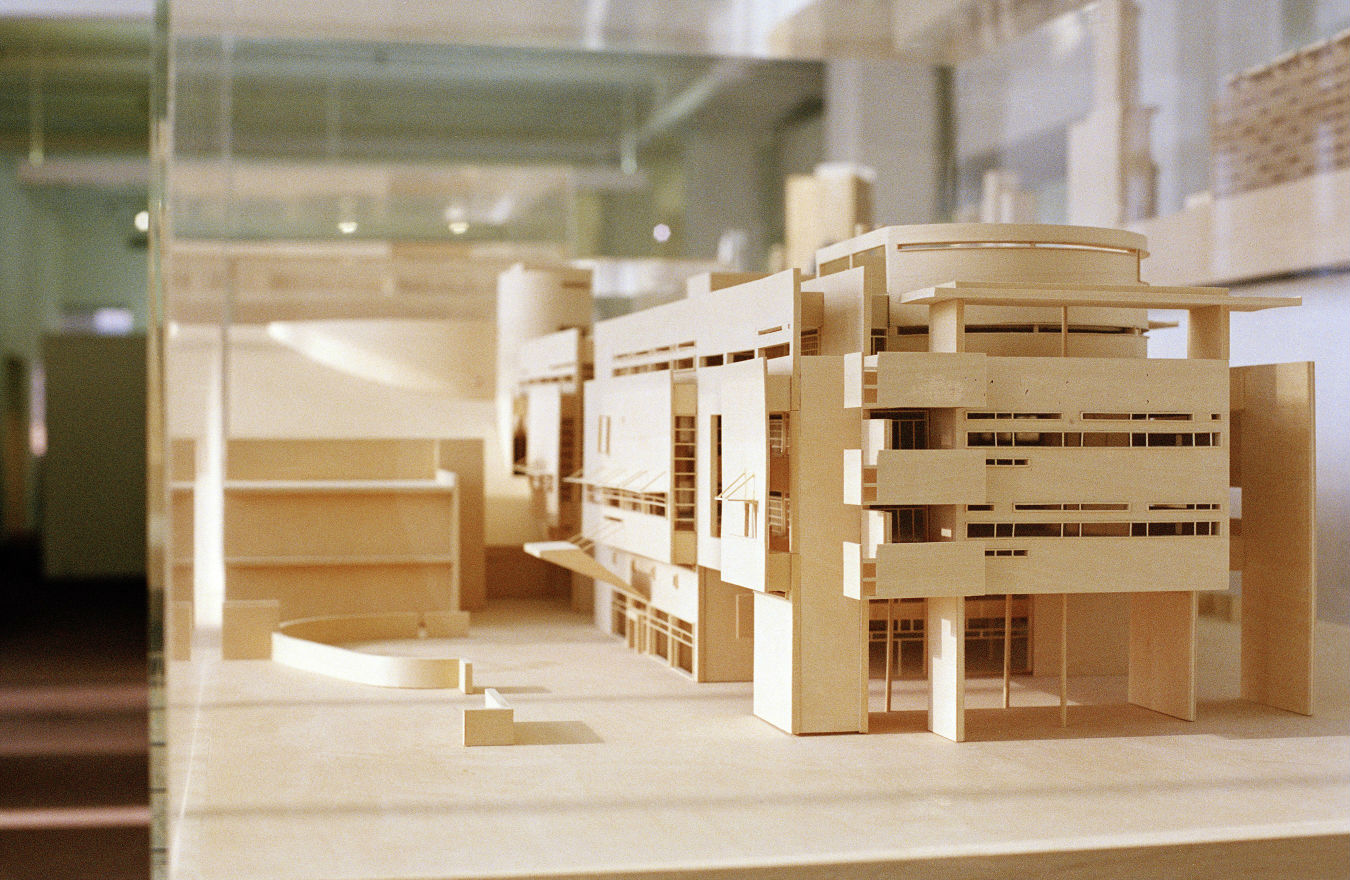

A model for the Euregio Office Building in Basel, Switzerland, 1990–1998.

-

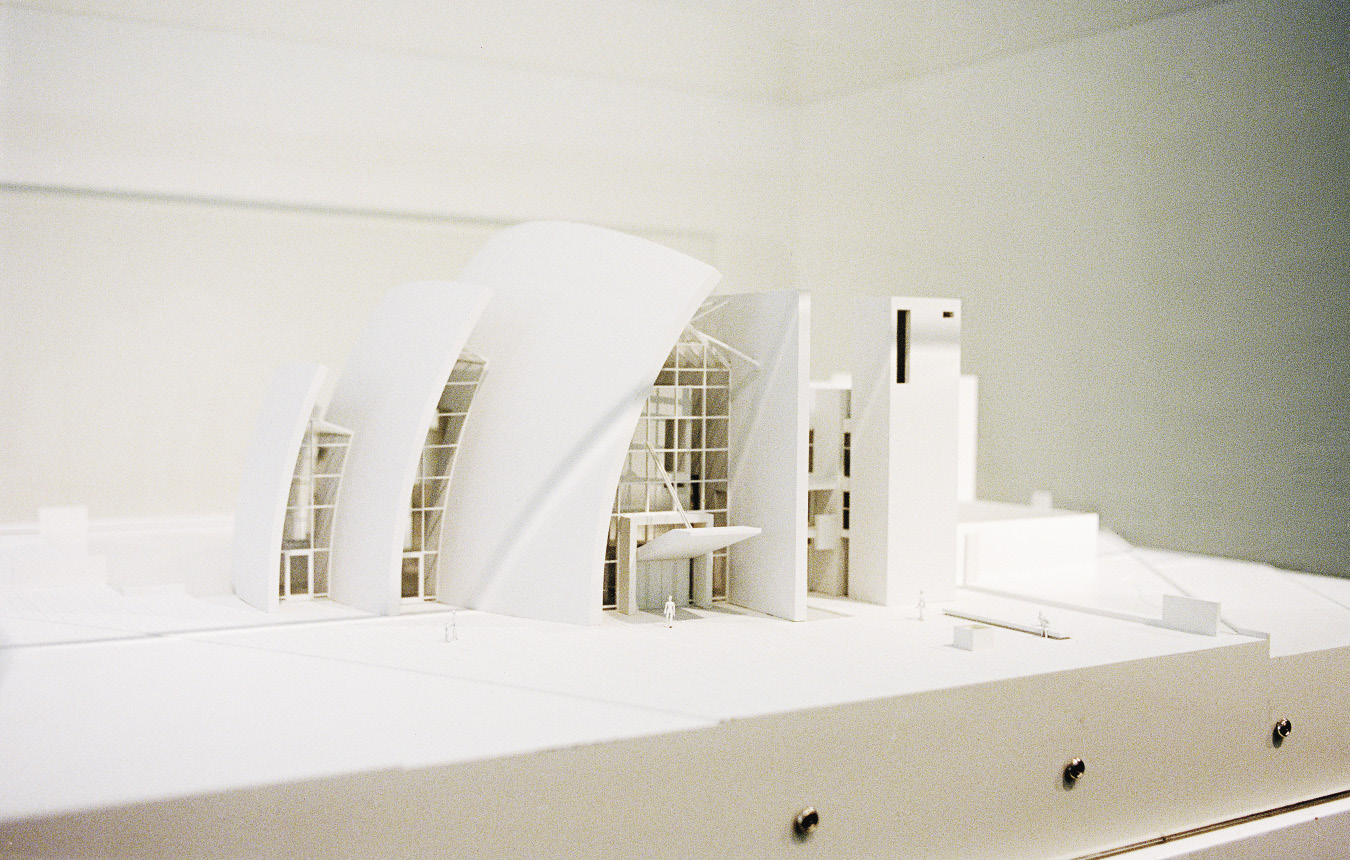

A model (unbuilt) for the Eye Center for Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland, Oregon, 1987.

-

Models inside the Richard Meier & Partners Architects office in New York.

-

The Surf Club Drawings, Surfside, Florida, 2012.

Richard Meier

Building truths.

It’s another sunny December day in Miami, and all over town thousands of visitors are flocking the city’s convention centres and galleries for the week-long marathon that is Art Basel and Design Miami. The twin fairs are in full swing, and the traffic along Collins Avenue is backed up all the way down to South Beach—though you’d hardly know it sitting in the tranquil central plaza of the Surf Club, up at the northern end of the beach near Bal Harbour.

There, ensconced in a large metal chair beside the swimming pool, a man in a decidedly un-Miami-ish dark suit with white, wispy hair is holding court. His interlocutors, a few of them standing and sitting in an arc around him, seem to be doing most of the talking. Every now and again he gestures vaguely with the cane in his left hand and then settles back into a smiling stillness, staring off at something in the middle distance from behind his rounded, black sunglasses.

At 79, Richard Meier has earned the right to do and say—or not do and not say—pretty much whatever he pleases. He’s won nearly every major accolade the design world has to offer, including the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 1997, the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1988, and the crowning glory, the Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 1984. His New York–based office, Richard Meier & Partners Architects, has completed projects on five continents, some of them (Los Angeles’s Getty Center, the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, and the breakthrough Smith House of 1967, to name but a few) being generally reckoned among the canonical works of late 20th- and early 21st-century architecture. After all that, and so much else, surely he deserves a few quiet moments in the Florida sun.

But Meier didn’t come here for his health. “Miami is a city that’s always been open to modernism,” he says—and as he is perhaps the foremost living exponent of modernist architecture, that means Miami is open to Richard Meier. After a false start six years ago, when his putative Beach House project fell through in the midst of the global financial downturn, the architect is back in town to launch what will be his first project in the city: a reinvention of the faded mid-century Surf Club as an all-new mixed-use condominium of curving towers with gleaming glass façades, luxury living as only Meier could imagine it.

Inside the office of Richard Meier & Partners Architects in New York.

And that’s not the only way he’s keeping busy. In a spate of new projects, Meier is blazing an unusual path for an architect who’s been active as long as he has. Like artists, architects are known to develop a “late style”; Le Corbusier (Meier’s hero) is a classic example, moving from his well-known white geometric buildings of the 1920s to a more expressive, sculptural mode by the 1950s. But at the far end of 50 years in practice, Meier still seems determined to develop in a less-linear fashion. “I really look at each project as a thing unto itself,” he says. If most architects’ careers can be said to trace an arc, Meier’s seems to be more like a tree, a central trunk of ideas and principles with each project representing a separate excursion in one direction or the other.

He’s keeping this focus on each individual project even as his latest endeavour has obliged him to come to grips with his career as a whole—and with his legacy to architectural history. Open to the public since January, the Richard Meier Model Museum occupies a single floor in a vast former industrial loft that now houses Mana Contemporary, an arts and culture space in Jersey City, New Jersey. Just a 20-minute drive from Meier’s offices on Manhattan’s West Side, the museum affords an opportunity to consider his work in the aggregate, to see just how massive his contribution has been and to understand something of his working method. Even Meier himself has been surprised at the volume of models his office has turned out over the years, shoved away as they were in a storage space in Long Island. “I didn’t know how we had it all out there,” he says. “I certainly didn’t realize what a monumental effort it was going to be getting it all to Mana.”

The move to Jersey is, in a sense, a homecoming for Meier, who grew up in the town of Maplewood, scarcely 24 kilometres down the road. Strange as it is to think of someone as determinedly urbane as Richard Meier growing up in the suburbs, he didn’t actually make the move to the big city until his mid-20s, after studying architecture at Cornell University and extensive travel abroad. As Meier recalls it, New York in the sixties was the perfect time and place for a young designer looking to get ahead, and he found early success with both private clients and public commissions. The city’s mayor at the time, John Lindsay, “was very favourable to things happening—very co-operative in getting zoning changes that we needed,” says Meier. With the help of City Hall, the architect was able to execute two of his largest early projects: the Westbeth Artists’ Housing project in Greenwich Village and the Twin Parks Northeast housing development in the Bronx.

A model for the Canal+ Headquarters in Paris, France, 1988–1992.

What brought Meier to a broader audience, however—and what’s made his name synonymous with the city he’s lived in for five decades—was his membership in the New York Five, an informal band of like-minded contemporaries who emerged in the late sixties and early seventies. Meier’s work of the period, along with that of friends John Hejduk, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, and Peter Eisenman (his second cousin and a fellow New Jerseyan), stood out for its modernist orthodoxy at a time when sci-fi architectural fantasies and backward-looking historical pastiche were increasingly in vogue. In the years that followed, each of the five developed his own markedly different style, and of them only Meier is still mining more or less the same echt modernist vein that he was 40 years ago. But what’s interesting in talking to the architect is hearing how little style as such enters into his own understanding of his practice and its defining principles. “The basic elements that I’d like to think that are in all my projects are things like a concern with public space—how do we create something which is not just satisfying to the client but to the people who live around it,” he says.

At the heart of Richard Meier’s work from the very beginning—in that core set of ideas from which each project springs—there’s been a commitment to an architecture of calm, reflective humanity, of simplicity and modesty.

Meier’s ongoing preoccupation with public space is evident in the finely wrought models, large and small, that pack the new exhibition venue in Jersey City. In a series of enormous wooden mock-ups of the Getty Center—some of them as large as two metres square—visitors can see how Meier considered and reconsidered the generous plazas, gardens, stairways, and receiving areas, shifting them slightly from model to model until he felt he’d achieved the gracious communal atmosphere that’s made the hilltop museum and research centre such a success. Elsewhere in the Model Museum, as in a smaller maquette of the 165 Charles Street apartment building in New York, it isn’t so much Meier’s familiar architectural language that makes an impression—the clean lines, the regular rhythm of the panels, and of course the ubiquitous white surfaces—but rather what’s behind that language, the sensation of light and clarity and tranquility. Meier’s models seem to bring to light the sensibility behind the style, and the architect is evidently pleased to give the public this sneak peek inside his practice. “We’ve had a very good response,” he says. “It’s just a great space.”

The Richard Meier Model Museum, a 15,000-square-foot showplace, took one year to plan and execute, while the archives and collection within took the work of several years, all of it going on alongside the heavy volume of new projects under way around the globe (Surf Club among them). Meier rattles off the rest of his current workload: “We have two buildings going up in Mexico City, two residential towers going up in Tokyo, a small building in Rio, we just finished a house in Luxembourg—we’ve got things all over.” Private homes and other more modest projects have never quite dropped out of Meier’s portfolio, and some of his current work is even smaller in scale than that; approval is pending from the City of Rome to retool a single travertine wall at his Ara Pacis Museum, after vociferous criticism by locals who complained that it marred the historic site. But if anything can be said to have definitively changed in the office’s output today as compared to 20 years ago, it’s that things have gotten much, much bigger. It’s a long way from Meier’s one-level, 1,425-square-foot Lambert House of 1961.

That creates problems as well as opportunities. “Suddenly there’s this challenge to deal with different sizes and locations,” says Bernhard Karpf, who has been working at the firm for nearly 30 years (and was made a partner 13 years ago). “High-rises require a different kind of thinking.” At the heart of Meier’s work from the very beginning—in that core set of ideas from which each project springs—there’s been a commitment to an architecture of calm, reflective humanity, of simplicity and modesty. These were the guiding principles for Meier’s early 20th-century touchstones, not just Le Corbusier but also Luis Barragán and Frank Lloyd Wright, and it’s worth noting that each of them often found it difficult to translate their small-scale thinking into more outsized projects. (Wright only executed one skyscraper; Corb’s later, larger work doesn’t have quite the verve of his smaller houses and churches.) The challenge for the practice, says Karpf, is “to move the iconic thinking on to the next level, the next size, without losing the core values.”

Early preliminary scheme of the Arp Museum in Rolandseck, Germany, 2002–2007.

For Surf Club, part of how Meier and his team have responded to that challenge is by making their 12-storey towers only part of a more varied ensemble that includes the historic central building and cabanas of the original resort that will be restored in the same design as the original. The latter, occupied in their heyday by notables like Winston Churchill and Elizabeth Taylor, will be preserved more or less as they are; the Spanish mission–style reception hall will be fully restored, with some regrettable later additions (including the roofing-over of an additional courtyard) pulled out and made to look much as they did 80 years ago. This isn’t the first time Meier has worked within a historic context—his Museum Frieder Burda in Baden-Baden, Germany, abuts a decorative 19th-century building—but here the new, glassy additions are carefully composed to give the older structures pride of place. Meier had originally thought that building on the site would be challenge—he had never undertaken a restoration project—until developer Nadim Ashi brought him to the location. “It just took half an hour when Richard saw it,” says Ashi. Meier needed little convincing to come on board, and to make the old Surf Club an integral part of the new.

So taken was he with the project, in fact, that Meier himself will become one its first residents; he’s agreed to take an apartment in the complex. This will be the first time Meier has ever lived in a building he’s designed himself, and given Miami’s reputation as perhaps the United States’ largest retirement community, this may sound alarmingly like a step away from the architecture trade. Yet even as he basks in the sunshine and the attentions of well wishers in the Surf Club courtyard, Meier is clear that he’s not looking to make an exit any time soon. A special studio was carved out of the back of his New Jersey model storehouse to give Meier a sort of artistic refuge, but he confesses he’s not certain he’ll make use of it. “I’ve got it all set up, but I don’t know what I’ll do,” he says.

In any case, rumination and late-life quietude do not seem to be in this architect’s repertoire. “Once you do a project, you don’t go back and rethink it,” he says. Pensive as his work can be, meditative as the spaces he’s created often are, Richard Meier is still too busy looking ahead to spend too much time reflecting on the past.