-

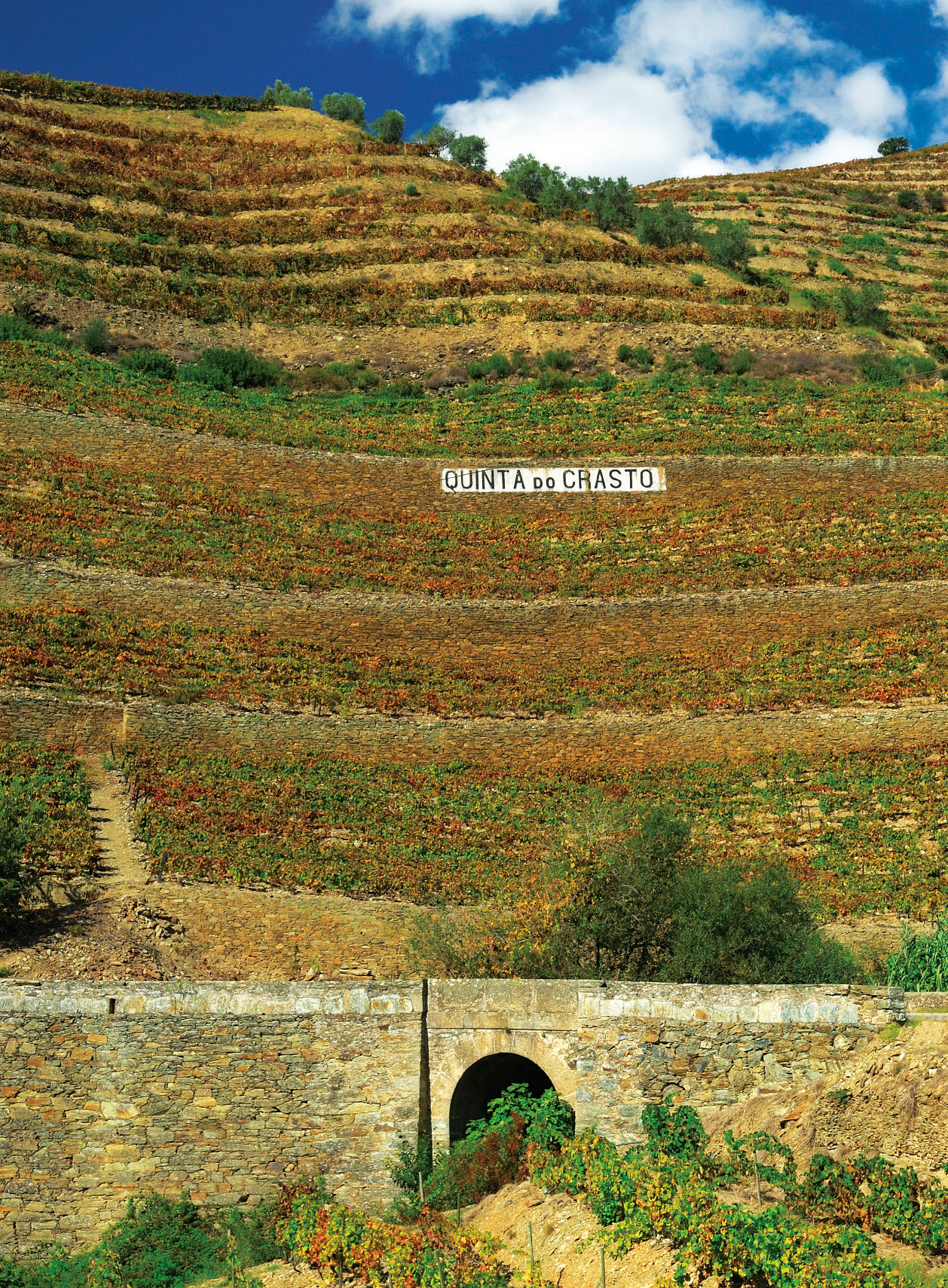

Quinta do Crasto winery and hacienda overlooking the Douro River.

-

The Quinta do Crasto Reserva wine.

-

A hand-built schist wall, common to the Douro region.

-

-

Quinta Do Crastro

Gold in those hills.

The flight into Porto, Portugal, from Frankfurt feels like riding in an air show, so many steep banks and turns are there. Still, it is not a bad feeling, especially after touchdown and entry into one of the airiest, cleanest, and brightest arrivals lounges in Europe. This feeling is a harbinger of things to come, and as Miguel Roquette pulls up to the front doors, a wine trip like no other can safely be said to have begun.

Miguel and his brother Tomås run the show at Quinta do Crasto; Miguel travels the world, representing the wines, while Tomås runs the winery operations, though their efforts are more symbiotic than the roles themselves might indicate. The expansive property is on the Douro River, just a 90-minute drive from the city of Porto up and over the Serra do Marão, past various vinho verde vineyards and numerous pousadas (luxury hotels) offering food and shelter for the night. There is no stopping Miguel, though. He gets into the Alto Douro wine region in good time, and then slows down, partially from necessity, partially from inclination, to wind along the narrow roads which are often bordered on one side by a steep bank of mountainous soil and rock, on the other by a precipitous drop.

The Douro Valley, with a river running through it (d’oro, of gold, refers to the colour of the water at sunset), is home to Portugal’s port wine industry, and covers more than 250,000 hectares, just over 45,000 of them planted with vines. Of those planted hectares, 30,000 individually owned plots are smaller than one hectare, giving you an indication of how business is run. The big port houses, most of them internationally owned—the Symington family of Britain owns the largest by far—buy grapes mostly from contracted farmers. Each farm or estate is called a quinta, and many of those have large signs erected on the steep hillsides, announcing their domain. Quinta do Crasto, in fact, makes a tiny amount of its own port; but the big story is that this family-owned winery, encompassing 130 hectares, 70 of them planted, is now making world-class red (and a small number of white) table wines, from select portions of the vineyards that grow the same grape varieties that go into making port. The Roquette family also now owns Quinta do Cabreira, which is a 90-minute boat ride up the Douro toward the Spanish border; it is 120 hectares, 80 of them planted, a stunning sight on the steep hills of the Upper Douro.

There are well over 100 indigenous grape varieties grown in the Douro, none of them known to be grown commercially anywhere else in the world. The most prominent of these, perhaps, are touriga nacional, tinta roriz (known in Spain as tempranillo), and touriga franca. What these varieties all have in common is a thick skin and good maturation, which means they can withstand the temperatures of the sunny hills banking the Douro, which often reach the mid-40ºC range for weeks at a time in summer. Familiar varieties like cabernet sauvignon and merlot would simply bake in their juices in those conditions. The native varieties are also able to thrive in reasonably harsh soil conditions.

“Every time I get to the Douro, there is a different light, and a different smell,” says Miguel. “Familiar, but always different, and not like anywhere else in the world.” He stops the car, puts his hand out the window, and gently tugs at a piece of rock. “This is the key to the Douro. It is schist, the main component of all the hills around here.” Schist is a metamorphic, highly foliated rock, meaning that it breaks easily into small slabs or even flakes. It is everywhere in the Douro. Crasto has actually used black schist as fencing in many locations, remarkable emblems of the terrain, and the hard human labour it takes to get anything grown here.

Schist rock, steep hills. These result in the wonder that is a trip up the Douro River, which at every turn, at every new vista, reveals vast retaining walls, built centuries ago, from the schist. These mini-walls were used to shore up little plots of arable land, in which corn, beans, olive trees, and, of course, vines could be planted. The law in Portugal is that anything steeper than a 35-degree grade must be planted on these terraces, and not as vertically planted vineyards. In fact the first vertical plantings are quite recent, and not numerous, so clearly the effort to plant anything in these hills involves enormous human labour.

The port wines are a story for another day. Quinta do Crasto and the Roquettes are part of what they call “the Douro Boys”, which also includes Quinta do Vale D. Maria, Quinta do Vale Meão, Quinta do Vallado, and Niepoort. Together these wineries are establishing that table wine from the Douro ranks with the finest in the world. A daunting task, but well underway. Says Miguel, “I travel probably five months of the year. But I never get tired of talking about our wines, and this wonderful place.” He waves his hand for emphasis.

Around the next bend is Crasto itself. “Still a work in progress, in terms of hospitality, accommodations.” But they have their priorities straight, here, and the first of those is to make the best wine possible, which means growing the best fruit possible.

“We are just winemakers. What comes into the winery, the fruit, is the most important thing. It is what makes these wines so interesting, so great.”

At Crasto there is a small hacienda-style house, built on a ledge just above the winery itself. The home was built by the Roquette brothers’ great-grandfather at the beginning of the 20th century, and remains remarkably intact, with a few concessions to modernity like electricity, running water, and air-conditioning. The house is surrounded by vineyards, but also features a marvellous garden, from which the occupants of the house can be fed virtually all year long. There are herbs, tomatoes, potatoes, corn, artichokes, beans, lettuces, onions, raspberries, and root vegetables. There are orange and grapefruit groves, honey figs, pomegranates, rows of almond trees, and olive trees everywhere.

A snack of roasted almonds, cheese, and cold, raw percebes (gooseneck barnacles) precedes a dinner of bacalhau, followed by new potatoes, beans, carrots, some prawns, and Douro beef. Dominic Morris, winemaker at Crasto since 1995—who runs his own boutique winery in his native Australia as well, called Pondalowie (“Hard to say, easy to drink,” he says wryly)—is in attendance. The wines are chosen for their representative qualities, and approachability: the 1997 and ’01 Quinta do Crasto Reserva; the ’98 Vinha Maria Teresa single vineyard; the ’00 Vinha da Ponte single vineyard; the ’01 Touriga Nacional; the ’03 Tinta Roriz; and the ’07 Maria Teresa cask sample. Tomås, Miguel, and Dominic are a study in contrasts as they approach these spectacular wines. Each finds charm in every glass, but each also has distinct preferences. What is striking about this tasting is how well the wines perform, and how they evolve in the glass over 30 to 40 minutes. The two single vineyard wines are located only a few paces from each other, on the hill below the winery. Yet there are profound differences; the expression in Ponte is quite dark, deep, and brooding, while Maria Teresa has similar weight and structure, but is redolent of raspberry, chocolate, and blackcurrant, while the Ponte is all herbs, liquorice, and ripe plum. Only a few thousand bottles of each are produced, and even then only in what Miguel and Tomås deem “exceptional” vintages, so this is rare air in the wine world—which has taken notice. Dominic sits back and says, “These wines just prove it, without a doubt. We are just winemakers. What comes into the winery, the fruit, is the most important thing. It is what makes these wines so interesting, so great.”

Still, given their magnitude, the single-variety wines are at least as much of an accomplishment, taking grapes that are known to be monolithic and making them into graceful, even elegant expressions of the Douro’s soil and its indigenous grapes. All the more wonder that the Reserva seems to hold its own at this table. It is a wine available around the world, and a bargain at the $43 or so it fetches in Canada. All told, this evening’s table is laden with some of the finest wines produced on the planet, and the Roquettes’ strategy—to showcase the region, and Crasto itself, by demonstrating the high levels it can regularly achieve—is manifestly sound.

Jorge Roquette, retired banker, is the patriarch of the family, and his vision, formed back in the early 1980s, was to bring Douro table wines to the international stage. Over a dinner of fresh spear-caught sea bass and new potatoes, he is a charming, charismatic figure. “Tomås and Miguel are doing very good work, I think,” he nods, and adds, “It is a difficult thing, to establish market for the wine. But our priority from the very first day was to bring the vineyards to the highest standards.” The brothers agree, and Tomås says, “That is the key. We have to make special wines, unique wines, and the only way we can do that is ensuring the vineyards are top-notch.”

Jorge inquires about a boat trip to Cabreira. It involves going through two large locks on the river, and features vistas that encompass all the major names in the port world. Cabreira, though, with its newly planted terraced vineyards, is a breathtaking sight, and a truck ride through the vineyards, with all those precipitous drops just out the vehicle door, is a white-knuckle experience all its own. “Don’t worry,” says Miguel. “We have never had an accident. We are like mountain goats here—we are used to the heights and the narrow roads.”

While plans for accommodation and a residence are still a year or two away, the vineyard project should begin to yield usable fruit soon, and then decisions will have to be made about how to incorporate the fruit into the Crasto line of wines, and whether to bottle some wine under the Quinta do Cabreira name as well. These, though, are pleasurable challenges.

The boat ride back to Crasto late in the afternoon has Miguel feeling a bit philosophical. He is flying Portuguese flags from the stern of the boat, port and aft, and as he glides past some of the glorious estates that bank the river, he murmurs, almost to himself, “We Portuguese need to be more proud of who we are. That is part of what we are doing at Crasto. But in order to do that, we must, must, must make fantastic wine. Wine so good no one can argue with us about quality.”

Back at the hacienda, over a dinner of hake, langoustines, more percebes, and a little pasta, the infinity pool glistening in the fading light, it is impossible not to be optimistic for Miguel and Tomås. Two massive Portuguese sheepdogs, one around 60 kilograms and the other, still a puppy of only a few months, closer to 40 kilos, ceaselessly roam the yard, often stopping to bark at some unseen would-be intruder. Pipo and Tinto are their names, and they act as familiars, keepers of the spirit of this place. Late into the night, the darkness complete so far away from any city, the dogs keep their vigil, and it all feels exactly right. Then again, it could have been that last glass of Maria Teresa working its magic, stars vivid in the summer sky.