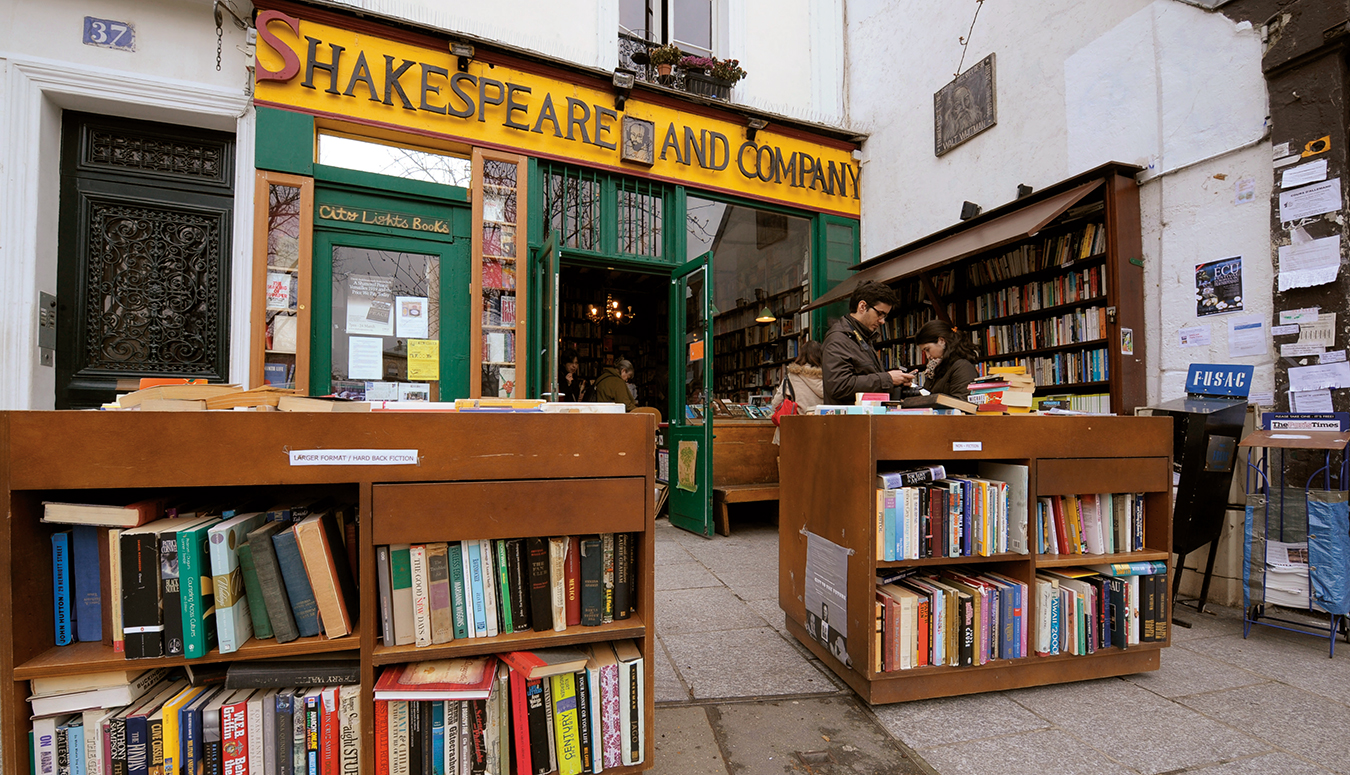

Shakespeare and Company Bookstore

A literary haven.

Books crammed in from wall to wall and from floor to ceiling, hand-lettered signs, a feeling of bohemian creativity, empty wine glasses that will be filled at the conclusion of this fictional book-reading. The opening sequence of the 2004 movie Before Sunset deftly conveys the intimacy at Shakespeare and Company, the mostly English language bookstore beside the Seine that is synonymous with the “lost generation” of expatriate writers and poets who, for a brief, intense period, made Paris their spiritual home. But the cinematic version takes one serious liberty: its sparse audience of actors. “Not a very successful author,” jokes Sylvia Beach Whitman, who has run the store for the past five years.

Made up of all ages and many nationalities, tonight’s audience is real, packed tightly together on stools the size of dinner plates. The questioning is lively at the conclusion of Welsh writer Carole Seymour-Jones’s reading from A Dangerous Liaison, her exposé of the relationship between Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Sartre compromising with the Nazis? De Beauvoir as pimp? This slant is daringly subversive, suitably enough because audacity and going against the current have always been the hallmark of Shakespeare and Company. The first to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses, it also brandished its independence by selling D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover when it was banned elsewhere.

Founded by American expatriate Sylvia Beach in 1919, and originally located at rue Dupuytren and then at rue de l’Odéon, the bookstore and lending library became a haven for just about anyone from the golden era of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Henry Miller, and other writers who preserved the time in verbal amber. When the Second World War ended, Hemingway, who had written about the shop in A Moveable Feast, took his tank and “liberated” Shakespeare and Company—but Beach, tired out, never reopened the store.

In 1951, another expat, George Whitman (no relation to Walt, that’s just apocryphal) also opened a bookshop, which, in 1962, with Sylvia Beach’s full approval, he renamed Shakespeare and Company. George Whitman, 95 this past December, still lives upstairs. His daughter Sylvia Beach Whitman (named in honour of the original store’s founder) is petite, fair-haired, and in her late twenties. She remembers a fairytale childhood growing up surrounded by books and authors. “Lawrence Durrell spent a lot of time here,” she says.

Shakespeare and Company has never been in lockstep with conventional opinion or business practices. In an age when books are increasingly viewed as commodities, the store only acquired a computer a year and a half ago. Today, Sylvia is working on it with a colleague, building the foundation for the store’s next biennial festival in June 2010 (the focus will be Politics and Storytelling). Right now, she’s contacting A-list authors to take part in readings and panel discussions under a marquee in the square. “We’re excited about the theme because there’s so many voices you can put to that,” she says. The most recent festival, which delved into Memoir and Biography, drew authors like Jeanette Winterson and Alain de Botton.

Steps from the stone lacework of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Shakespeare and Company is set back from the roaring traffic of the quais. Outside, shoehorned into cartons, ranged on tables and shelved alphabetically, are secondhand books, paperbacks mostly. Close your eyes, pick, and you’re just as likely to pull out a George Sand as a current murder mystery.

The shop houses mostly modern first editions, many from the lost and beat generations. Upstairs from the main store is a warren of small rooms and a reference library where anyone is welcome to read or study. Also upstairs are the “tumbleweeds”, George Whitman’s term for the aspiring writers who have stayed here over the years. The majority who come through are unpublished. “They just have to talk to me about what project they’re working on,” says Sylvia. She can’t keep track of how many, from around the world, have had a roof over their head courtesy of Shakespeare and Company. “It’s not a very pretentious atmosphere,” she says. “It’s for people who love books.”

In return for a bed, food, and like-minded company, all that’s asked of the tumbleweeds is that they work a few hours in the shop and read every day. “People imagine that you sit behind a till and read Jane Austen,” says Sylvia—but that’s unlikely. Along with selling books and stocking shelves, work involves fielding questions and stamping purchases with an insignia made up of the Bard’s head, the store’s name, and “kilometer zero Paris”, which marks the official centre of Paris, just outside Notre-Dame Cathedral, where the measurement of main highways begins, just across the river from the city’s literary heart.

Photos by Pascal Gely.