-

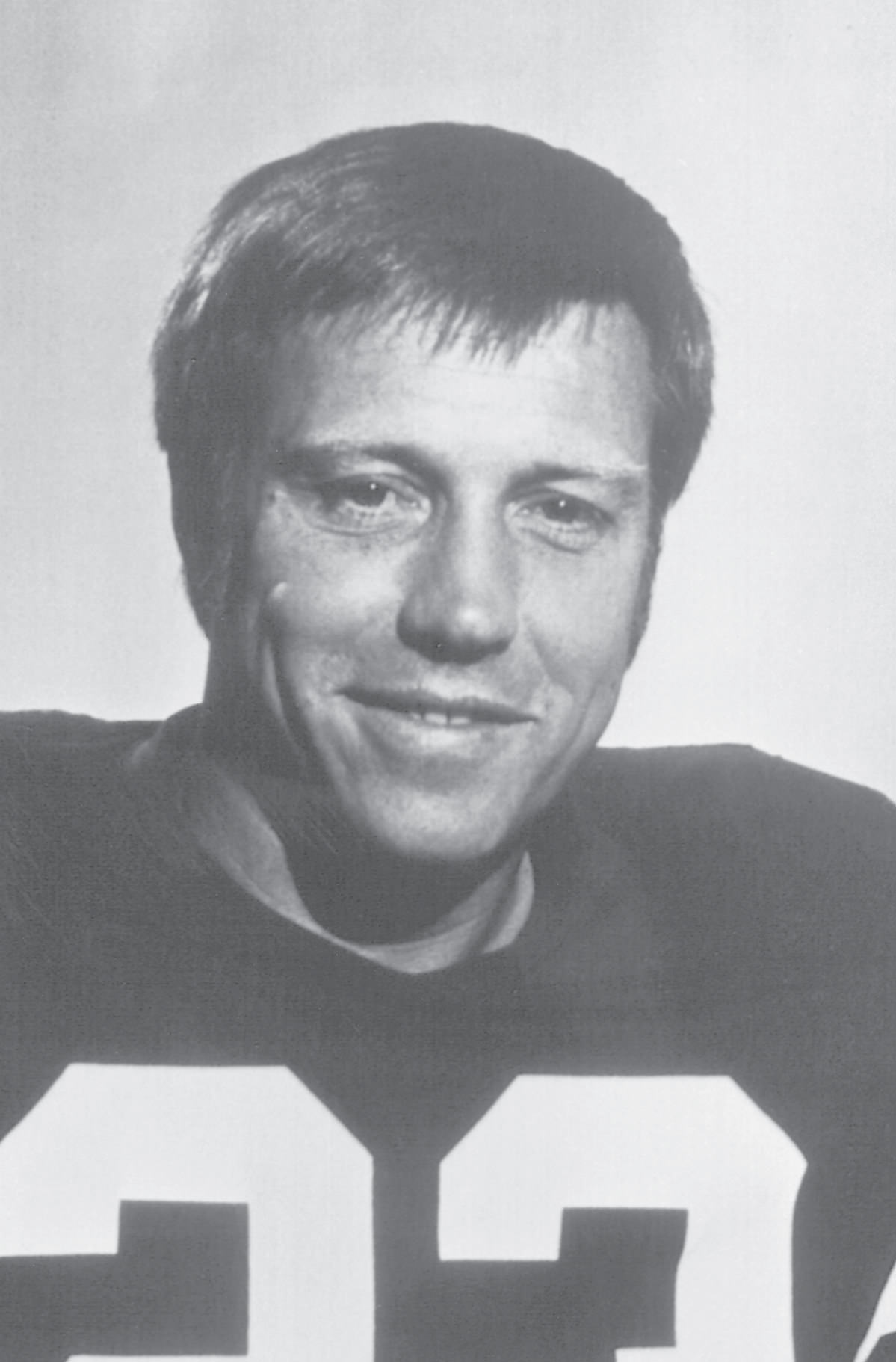

Lancaster handing off to power runner George Reed at Taylor Field. Photo: Regina Leader-Post.

-

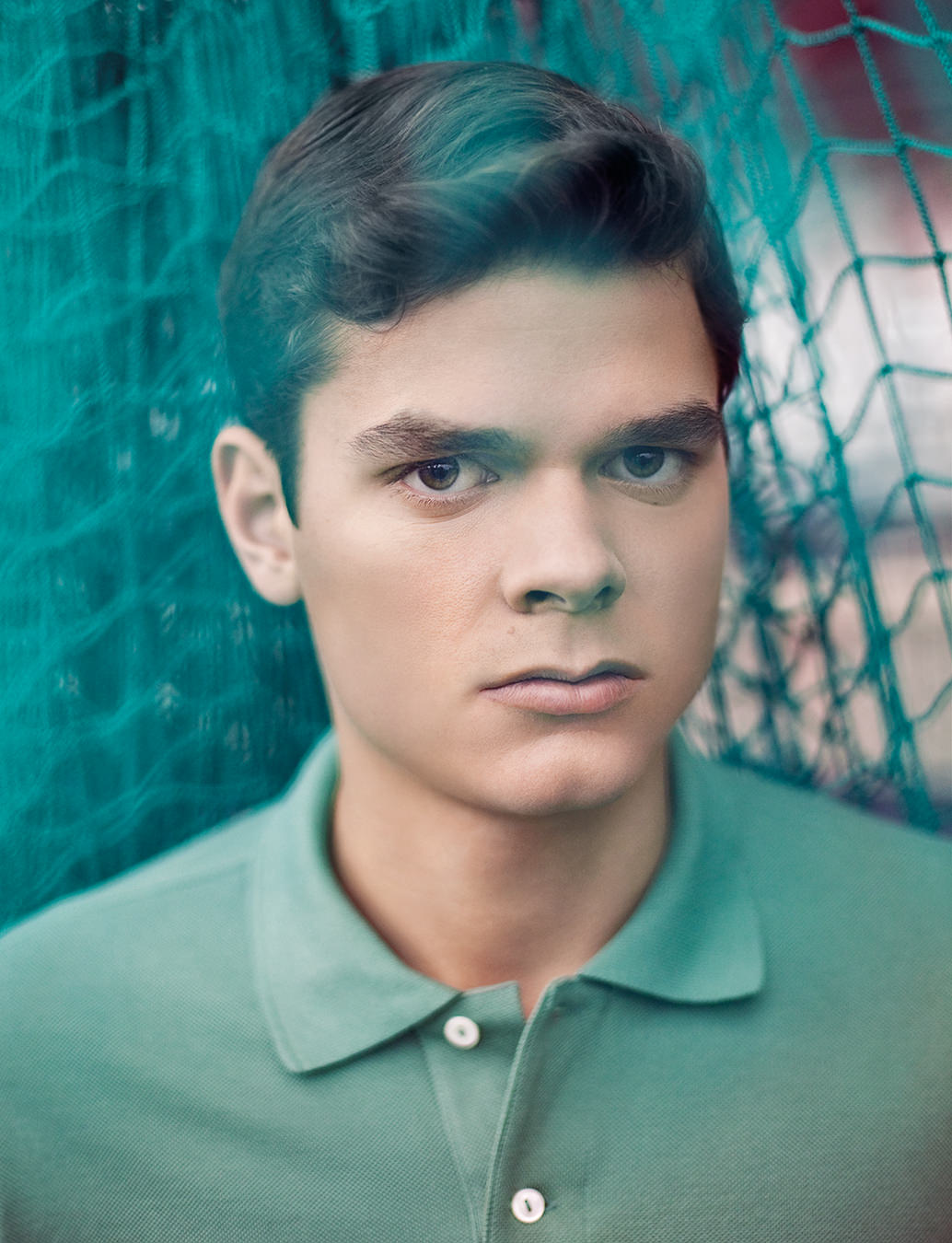

Lancaster in an Ottawa Rough Riders uniform. The only problem: Ottawa already had a quarterback, a guy named Russ Jackson.

-

Wrapping up his Schenley Award in 1970. Photo: Canadian Football Hall of Fame.

-

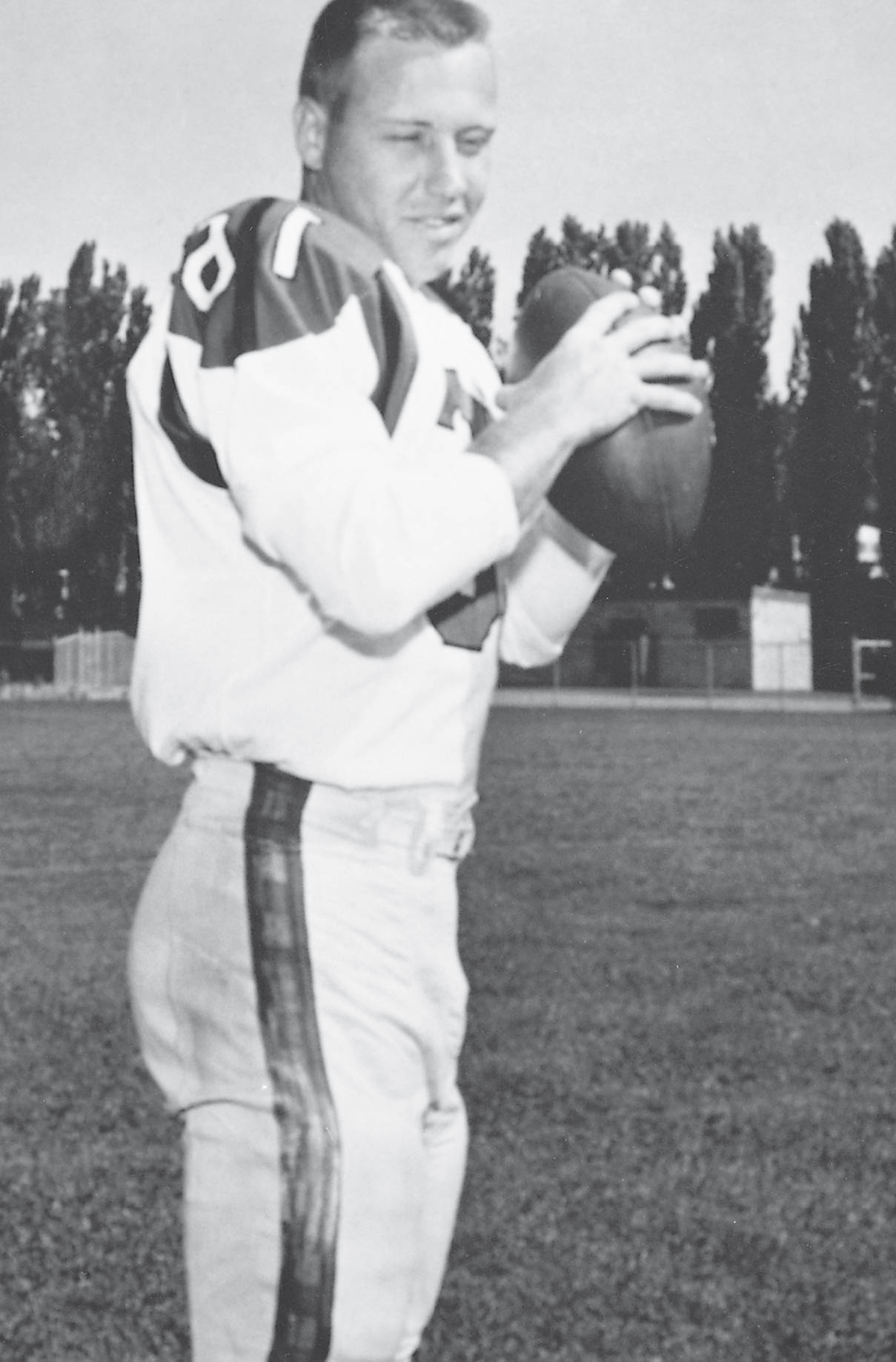

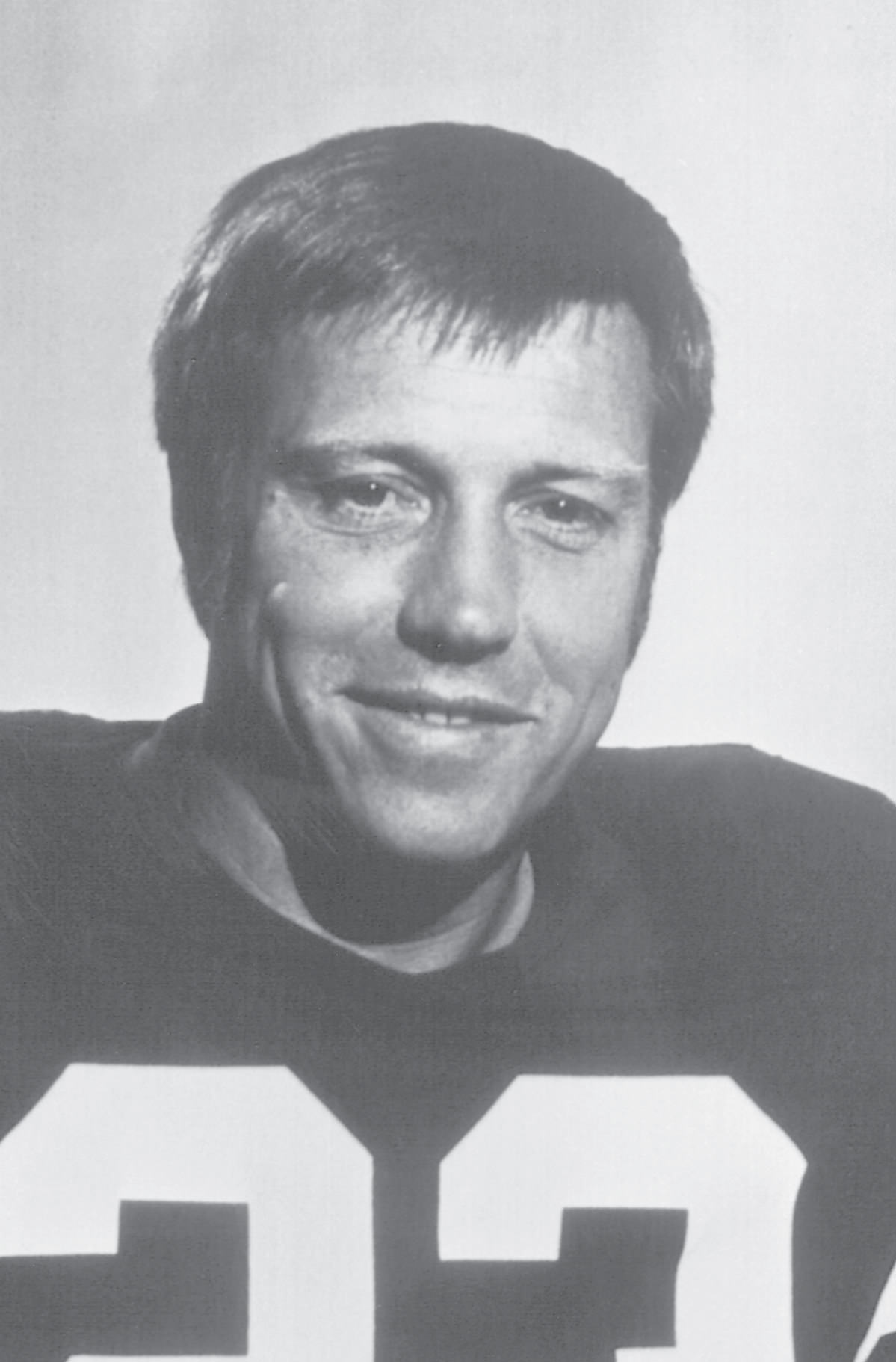

Lancaster in Rider green—his Hall of Fame portrait. When he retired as a player, his number, 23, was retired with him.

-

Brian Williams, Steve Armitage, Don Wittman, Scott Oake and—still controlling the ball—Ron Lancaster.

-

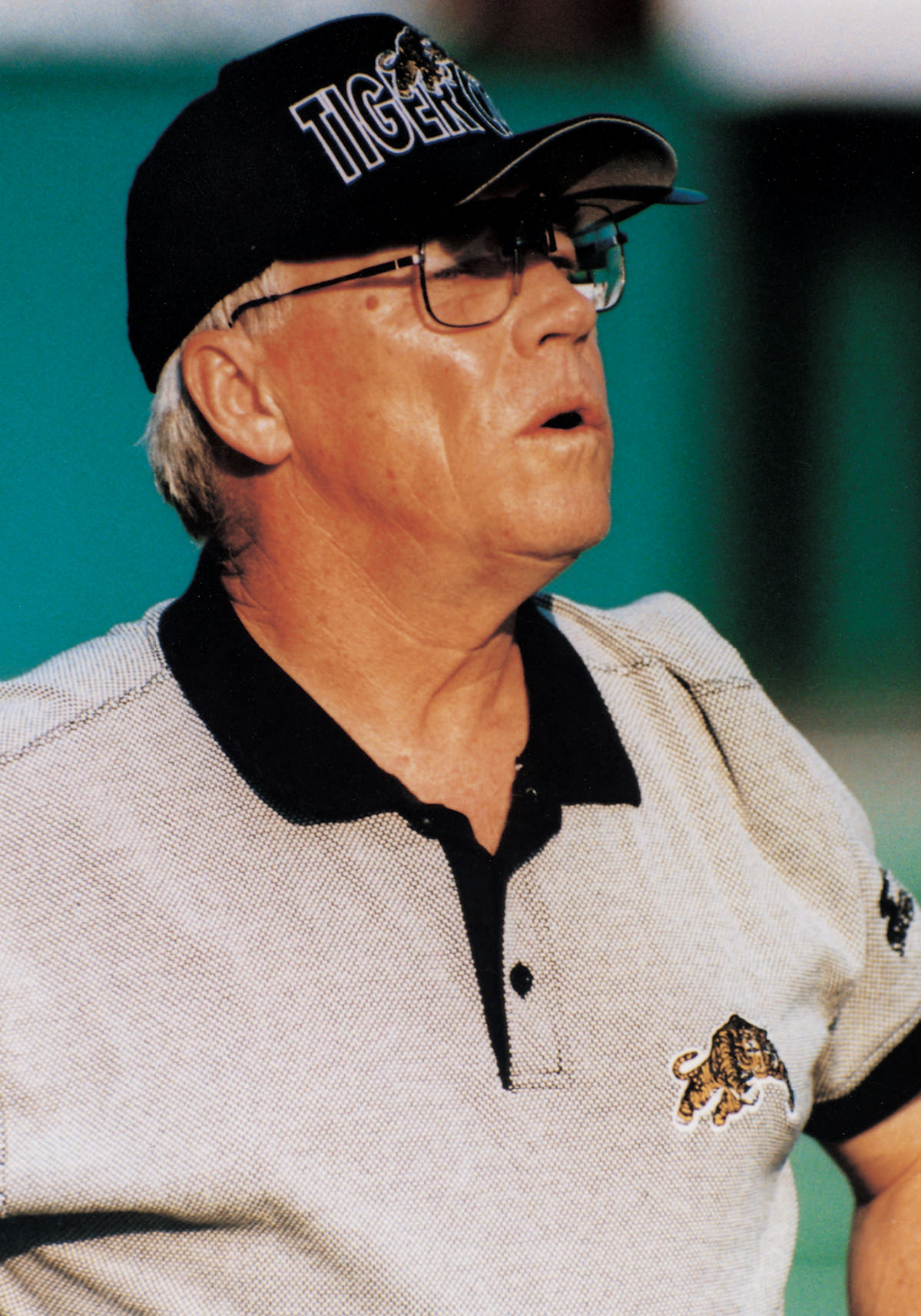

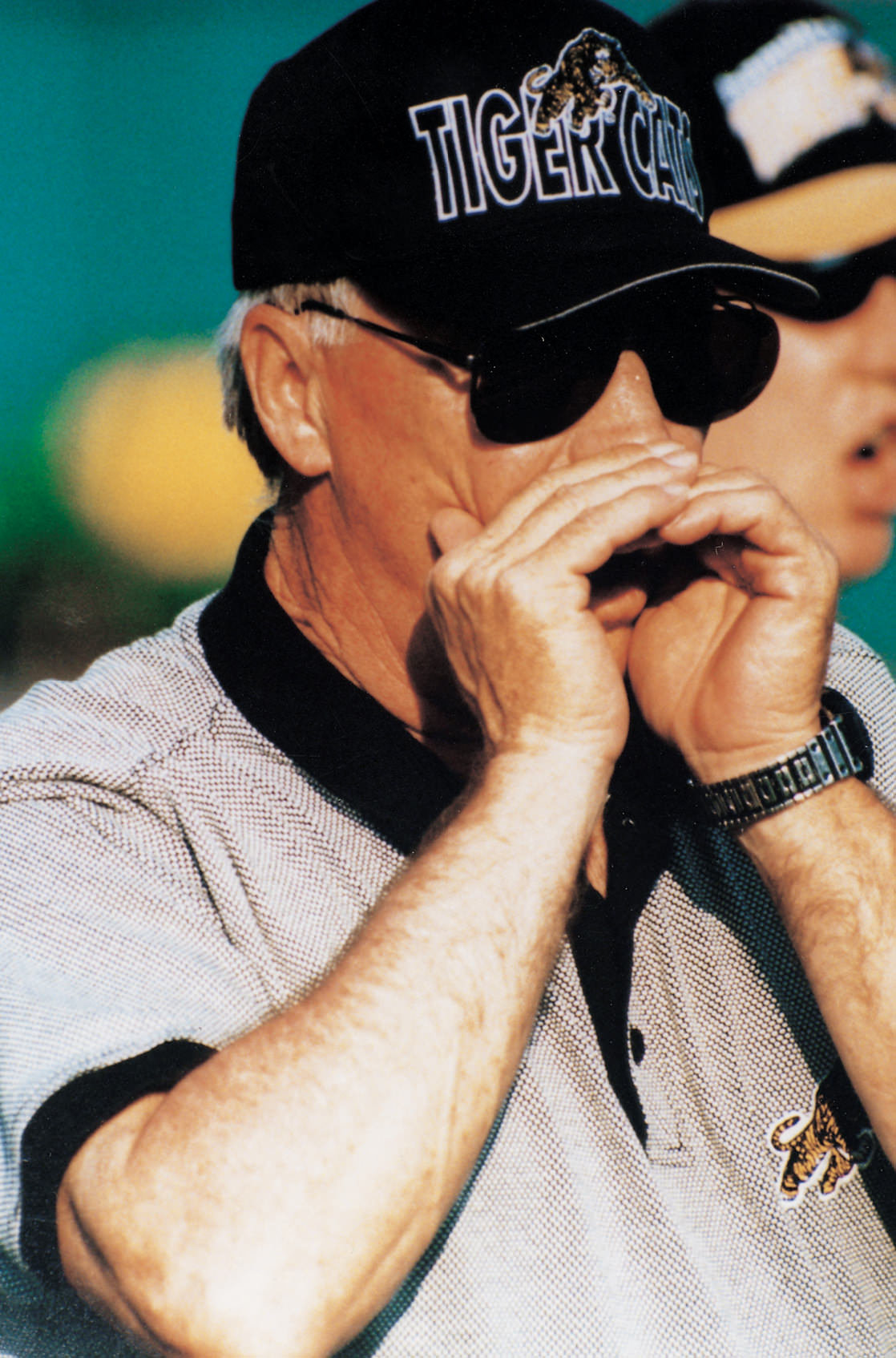

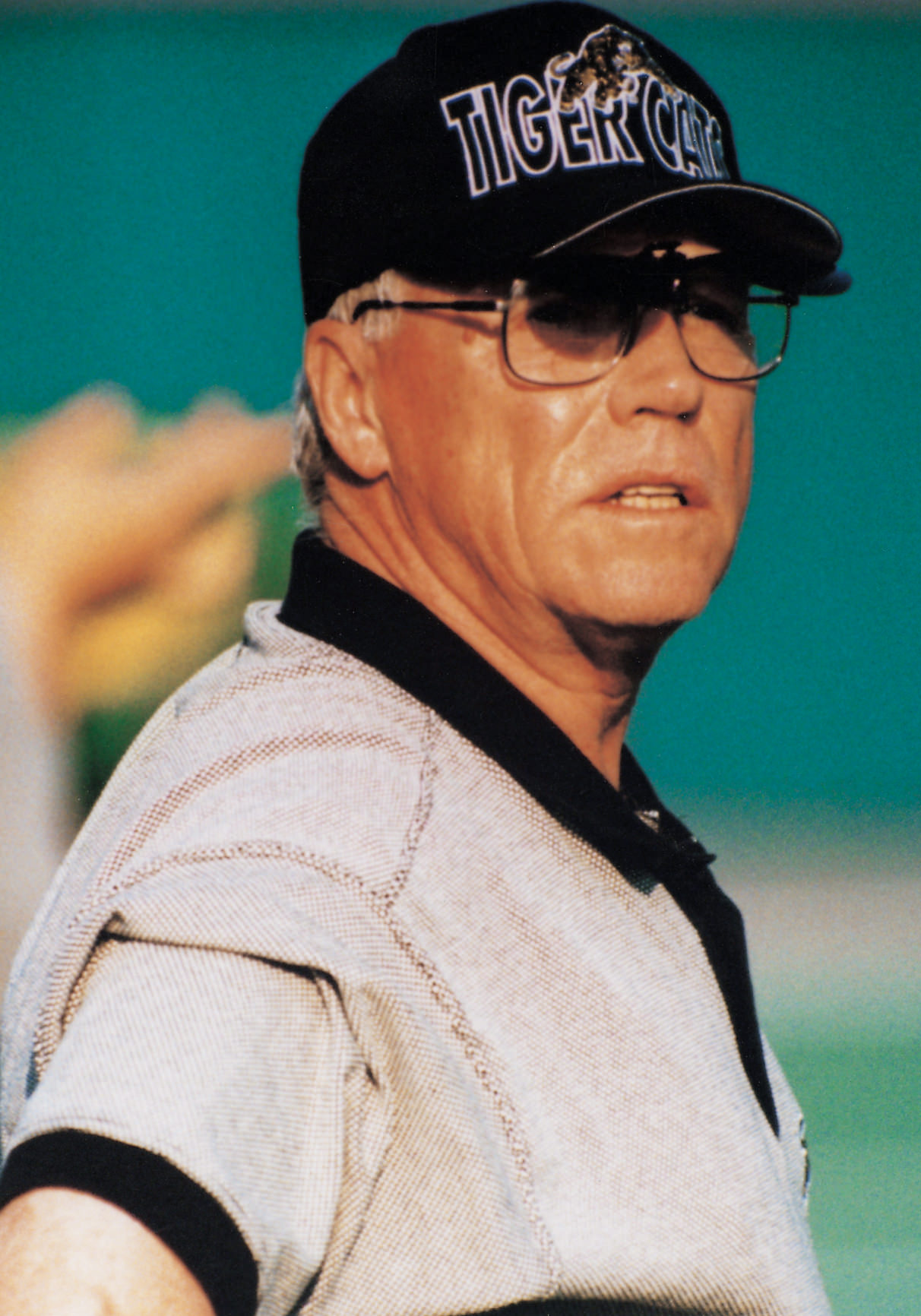

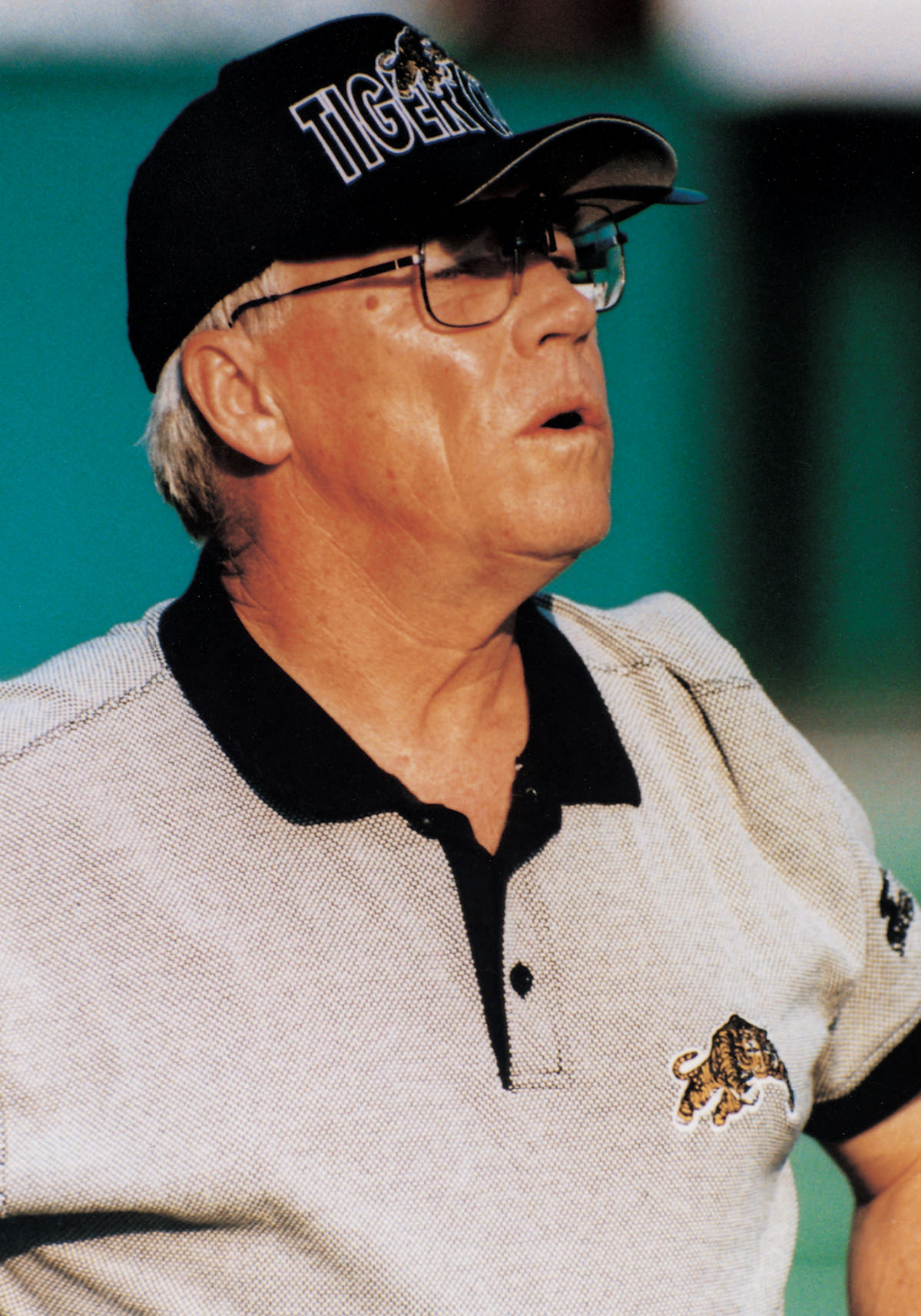

The coach considers a call at Ivor Wynne Stadium. Doesn’t care for it. Photo courtesy of Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

-

Photo courtesy of Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

-

Photo courtesy of Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

Ron Lancaster

Back in the pocket.

Wrapping up his Schenley Award in 1970. Photo: Canadian Football Hall of Fame.

Ron Lancaster doesn’t talk about the past. Even though there’s a lot worth talking about: four times a Canadian All-Star, seven times All-Western All-Star, twice Schenley Award winner, twice CFL Coach of the Year and four Grey Cup rings. Twenty-two years after his playing career ended, he is still the league’s career passing leader and one of an elite group of quarterbacks in any North American league to rack up more than 50,000 yards in the air (his total of 50,535 yards is topped only by Doug Flutie, Warren Moon, Dan Marino and John Elway).

But dealing with the realities of here and now, an absolute focus on the present tense, is the way Lancaster gets things done. It’s proven a successful strategy for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats’ seventeenth head coach and director of football operations. When he arrived in Steeltown, the Cats were hurting. They had finished the 1997 season with a dismal 2-16 record, a long way from the performances that made them perennial Eastern champions in the 1950s and ‘60s and brought them four Grey Cup wins between 1957 and 1967. They took the Cup again in 1972 and once more in the ‘80s, but years of steady decline followed and ticket sales slumped. New owners David M. Macdonald and George H. Grant were eager to sign a coach with a winning formula. Call Lancaster.

Ron Lancaster was born October 14, 1938 in a Pennsylvania steel mill town nine miles from Pittsburgh. He spent his college years as quarterback at tiny Wittenberg University, a Lutheran school of about 1,500 students in Springfield, Ohio, and led his team to Ohio Conference championships in 1957 and ‘58.

Lancaster handing off to power runner George Reed at Taylor Field. Photo: Regina Leader-Post.

Lancaster was listed as 5’10”, but, like Doug Flutie after him, was probably shorter, and American scouts would consider him too small for the US pro game. So in 1960, the year after graduation, he joined the Ottawa Roughriders. The only problem: Ottawa already had a quarterback, guy named Russ Jackson. So Lancaster started as defensive halfback.

But halfway through the season, Jackson was injured. Lancaster was in as QB and he led the Rough Riders to a Grey Cup win. “Then we had the two quarterback system,” Jackson recalls. “We won the Grey Cup and everybody was happy.” But once Jackson was on the mend, the situation became difficult. “It wasn’t good for the team,” says Jackson. “The team has to know who’s going to play quarterback, and [often] they didn’t until the last minute. It affected the quarterbacking of both of us. You were always looking over your shoulder.”

After two more seasons, Lancaster’s contract was up and he was traded to the Saskatchewan Roughriders. He won out over two other players for the starting position and, says Jackson, “We both benefited and matured from being able to quarterback on our own fields.” Lancaster was never traded again, and when he retired after sixteen stellar seasons, the Riders retired his number 23 as well.

The Green Riders of Regina’s windy Taylor Field were mediocre at best in the mid-Sixties, but in 1963, the starting lineup included not only Lancaster but glue-fingered receiver Hugh Campbell and powerhouse running back George Reed, both from the University of Washington. All had played well in college, but had never had a shot at a pennant. “It was an accumulation of underdog players,” says Campbell, with a store of built-up competitiveness that was ready for a chance. And that chance came with Eagle Keys, a coach who recognized the team’s chemistry.

Lancaster in Rider green—his Hall of Fame portrait. When he retired as a player, his number, 23, was retired with him.

The Riders shot from third to first in the Western Division in 1966 with a 9-6-1 record. With the Divisional Finals, then a two-out-of-three contest, Saskatchewan dominated the Winnipeg Blue Bombers 14-7 and 21-19. And then went on to win the Grey Cup 29-14 over the Eastern champions—Lancaster’s onetime Ottawa team—in the battle of the Riders.

“Ron was very headstrong,” Reed remembers. “He said, ‘There’s just no way we won’t win.’ He said he’s gonna win if he just has time. If we had time, we could win a football game.”

“It was fantastic,” recalls sportscaster John Lynch. “Really incredible. They could make the big plays at the right time. Lancaster had the ability to pick apart a defence during the second quarter, then go back in and kill them in the third and fourth.”

“Ron was very headstrong, he said, ‘There’s just no way we won’t win.'”

Lancaster’s stats grew increasingly impressive over the years—more than 2,500 yards every season from 1965 to 1978, with a completion rate of better than sixty percent in 1966 and ‘76. He was dubbed “The Little General” in Regina. He doesn’t think much of the nickname. “I get called a lot of things,” he says. “That’s probably one of the nicer ones. I never look at all that stuff.“

Veteran CBC sportscaster Steve Armitage traces the nickname’s origin: “He was a great leader.” And “he has the ability to inspire leadership.” Campbell agrees: “Wonderful leadership. Smart as a whip and very competitive.”

Reed was pushing the record books at the same time. He logged more than a thousand yards rushing for eleven years between 1964 and 1975 (missing only 1970) and peaked at 1,768 yards in 1965. Campbell’s records are also on the books in Regina, along with those set by place kicker (and starting left guard) Jack Abendshan. Campbell is quick to remember all the others—“defensive backs, linebackers, all those players who never made it to the record books. They all contributed.”

“We had a very strong team belief,” says Reed. “The team was first, individuals second. No egos allowed in. It was off the football field, too. If a guy was having problems, if somebody was in trouble, we’d band together and deal with it before it got out of hand. We were pretty successful at that.”

The coach considers a call at Ivor Wynne Stadium. Doesn’t care for it. Photo courtesy of Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

That’s what Lancaster understands, as well as anyone else in professional sport; what it takes to be a team.

“If everybody starts pulling in opposite directions, the opposite direction meaning individual goals, you’re going to have problems. To me, football is the ultimate team sport. In hockey, you’re going to touch the puck and you’re going to get to shoot; in basketball, eventually you’re going to get the ball. In football, the offensive, defensive linemen, they could go their whole career and never touch the football.”

In Regina, Lancaster also taught high school, while his three children (two sons and a daughter) grew up on the Canadian prairie. He coached high school basketball and made innumerable public appearances. A great communicator, he became a much sought speaker on the corporate circuit, known for his easygoing personality and sense of humor, as well as his insight into the team-building process. Friends and colleagues (he and Campbell have remained friends for 37 years) speak of him as a devoted family man. “I think the world of him,” Campbell says. “He always takes the high road.”

Between 1966 and 1976, the Roughriders made it to the playoffs eleven times and were contenders in five Grey Cup games. Public response to the team’s success was huge. Saskatchewan, with one professional sports team, wrapped the Green Machine in a province-wide group hug. But in 1976, Saskatchewan lost to Ottawa 23-20, and the spark seemed to go out of the team. Lancaster took on double duty as offensive coordinator with the 1977 season, but the Riders slipped from first to fourth in their division, and down to the cellar in 1978, managing only eight points. Lancaster decided his playing days were done. But in his final game at Edmonton’s new Commonwealth Stadium, Lynch recalls, “He got the winning touchdown in the fourth quarter and the crowd cheered for a long time.”

The day he retired, Roughrider management announced his signing as head coach. Given Lancaster’s acute understanding of Canadian football and his people skills, it looked like a natural fit. But the Riders dropped from first to worst, squeezing a skinny 2-14 record for 1979 and ‘80. “Don’t forget,” says Lynch, “he had to replace himself.” John Hufnagel took over from Danny Sanders at QB to no avail. Lancaster’s contract was up and most of the media were not kind to their former hero. But Armitage is sympathetic. “You have to remember,” he says, “he left a legend and came back [to coach] a legend—but not as a coaching legend.”

Under pressure, dogged by talk that he held his job only by his reputation as a player, Lancaster didn’t have his contract renewed. And he knew if he couldn’t excel, it was time to leave. Friends believe the experience marked him deeply, but he didn’t have time to brood. Canny CBC-TV producers recognized an opportunity, and Lancaster was back in the game—or close to it. As color commentator for CFL telecasts, he followed the league across the country. Don Wittman was the regular play-by-play.

“What you saw on and off the camera was the same guy. He was folksy, entertaining, funny.”

“I was in the booth with him for ten years,” Wittman says. “He was an excellent commentator, one of the best in the country—maybe the best. He could read the play, figure out what they were going to do and why they were going to do it.” Armitage, who also worked the games, agrees, calling Lancaster “without question, one of the best color commentators.”

“He adapted to television,” says Wittman. “He understood it as a medium.” Armitage recognized “a natural ability to communicate. He was easy to work with. What you saw on and off the camera was the same guy. He was folksy, entertaining, funny. A color commentator only has 15 or 20 seconds to make an impression, and he did.” In 1988, Lancaster and Armitage were members of the CBC team that covered the Olympics in Seoul. Lancaster’s role: basketball commentator. “He was a good guy to travel with,” says Armitage. “He liked to play cards, drink a few beers.”

But despite Lancaster’s enjoyment of life as a sportscaster, being around the game isn’t the same as being in the game. Dissecting play after play from the broadcast booth inevitably added to his already formidable understanding of what it takes to win. And, Wittman recalls, “He often indicated that someday he might get back into coaching.”

Brian Williams, Steve Armitage, Don Wittman, Scott Oake and—still controlling the ball—Ron Lancaster.

Enter old teammate Hugh Campbell. After years as Lancaster’s favorite receiver, he had become head coach of the Edmonton Eskimos, leading the Green-and-Gold to an unprecedented string of Grey Cup wins from 1978 to 1982. But in 1990, he moved from the bench to the boardroom, joining the team’s executive group. With the head coach position vacant, he knew what to do: call Ronnie.

“It wasn’t Ronnie’s idea,” Campbell says. “I said come, be head coach. It took him about a week to decide. I really twisted his arm.”

Lancaster plunged back into the game, all the difficulties of the past seemingly erased. The Eskimos were coming off a 50-11 trouncing by the Winnipeg Blue Bombers at the 1990 Grey Cup. They finished best in the west in ‘91, but lost the Western Division final 38-36 to arch-rival Calgary. It was much the same story the following season, this time losing to the Stampeders by a single point. But the program was starting to kick in, and although the Esks trailed the Stamps by six points in divisional standings in ‘93, they muscled their way to the Grey Cup with a decisive 29-15 win. Lancaster got his first Grey Cup ring as coach when Edmonton kept the momentum going and finished 33-23 over the Blue Bombers.

After two years felled at the Western Finals, first by the BC Lions (against the up-and-coming Danny McManus) and then by the Stampeders, the Eskies made it back to the Grey Cup in 1996—this time with McManus on board. In a wild shootout in the snow at Hamilton’s Ivor Wynne Stadium, Lancaster’s Eskimos fell to Don Matthews’s Toronto Argonauts—and star QB Doug Flutie—43-37.

Lancaster addressed the media in full support of his team. “We had a great season and a great game,” he told Terry Jones of the Edmonton Sun. “There’s a lot of fight in these guys. We said we’d play sixty minutes and we played sixty minutes.”

“In his post-game speeches,” according to McManus, “he says ‘There’s nothing you can do about yesterday.’ He’s very positive—let the past go.”

In an ironic twist, in Lancaster’s last year with the Eskimos, Edmonton was held back at the Western Final by the Saskatchewan Roughriders. Someone in the booth must have said, “You gotta love it.” By this time, though, Lancaster may have tired of perennial Western Division victories, even bettering Campbell’s record for wins. At the end of the 1997 season, his coaching record was 83-43. He was named the CFL’s Coach of the Year and he was ready for a new challenge. He signed with the hapless Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

“The biggest thing he brings is mutual respect—’If you work hard and do the things I want, you will get the respect you deserve.'”

Though unfocused, the Cats had a pool of talented veterans on offence and defence, guys like centre Carl Coulter and wide receiver Andrew Grigg. The frustration of seeing their efforts wasted over several seasons had made them keenly motivated, ready to get with the Lancaster program.

Kicker Paul Osbaldiston, with the Ti-Cats since 1987: “The biggest thing he brings is mutual respect—‘If you work hard and do the things I want, you will get the respect you deserve.’ He’s got a no-nonsense, honest personality. As a player,” Ozzie says, “There’s no grey area.”

With Coach Lancaster, respect for the players has a practical purpose. “It all sounds good. Whether it works or not, you never know. Pure talent is number one, make no mistake about that, but after that comes chemistry. The people inside the locker room understand that as long as they’re playing well, we’re not going to bring other people in here. So they can relax. If they have a bad game, we’re not going to get rid of them. I tell them the first day of camp [that] hopefully, we’re going to find 39 guys we can start and end the season with.” This also creates an atmosphere that can accept new players quickly, should injuries to a player require a replacement. “When a new player comes in, he’s accepted right away. They want him to play well. They encourage him. It’s their football team,” says Lancaster.

“As far as [leaving] egos outside, it’s the one problem you have to corral,” the coach declares. There was a televised scene this summer that showed the superb running back and receiver Ronald Williams smoldering on the sidelines in the final quarter. Neither Ron talked to the media about the incident—too much class on both sides—but Williams was back in the next game, racking up two touchdowns.

Lancaster didn’t travel to Hamilton solo. He brought the core of the Eskimo game: son and offensive coordinator Ron D. Lancaster (dubbed ‘RDL’ by some of the players); QB Danny McManus; McManus’s favorite target, slotback Darren Flutie; and backup QB Cody Ledbetter. McManus says, “To be in three Grey Cups with him in four years—yeah, I can deal with that.”

The effect on the team was immediate. The Cats went from worst to first in the Eastern Division in 1998. Then, after beating Montreal by two points in the Eastern Final, Hamilton lost the Grey Cup to the Stampeders on a stunning last-minute field goal.

The 1999 season started with mixed results. Plagued by injuries to their defence, the Cats easily trounced weaker teams—Saskatchewan, Winnipeg—but didn’t seem to have what it took to get by the league’s best. A particularly dismal outing in Montreal left them with four injuries and a 52-19 loss.

Turning point: replacement players quickly fit in and the team came into stride at exactly the right time. After a hard-fought single point win over Montreal in the Eastern Final—characterized by Lancaster’s gutsy gamble of a third down pass—the Grey Cup re-match with Calgary proved far less competitive than observers had anticipated. The Cats brought home the Cup with a 32-21 victory.

For the Tiger-Cats, 1999 was a year for individual honors and milestones. McManus racked up a career high of over 5,300 passing yards, and over a thousand of those connected with Flutie. They made it look easy. McManus was named the league’s outstanding player.

Lancaster, poker-faced and gum-chewing in victory or defeat, is clear about his responsibilities: “My job is the product that goes out on the field. If I think I can do that by myself, I’m in la-la land. The coaching is done by the coaches—hire people that you trust and allow them to do their job. My job, the way I look at it, is to make sure that our coaches and myself get these players into a situation where they have an opportunity to be successful. That’s it.”

“I’m not the easiest person to get along with. People use the word stubborn. I prefer determined.”

As for the coaching staff, “Once the season ends, I don’t want them in here eight hours a day. Enough is enough. You need an outside life. I don’t care what time they come in in the morning, but I would really like them, after practice, to go home. Eat supper with their families and have an evening at home. You can get so engulfed in your job that you forget there are other things in life.

“This comes with my age,” he admits. “When I was younger, I wasn’t any different than anybody else.” He’s keenly appreciative of the supportive role his family has taken in his sometimes difficult professional life. His wife, Bev, “basically raised the kids, because I wasn’t around much. Looking back, with my kids raised and gone, I wish I had been.” Friends now note Lancaster’s close relationship with grandson Mark, often seen beside him at games.

Bev, he insists, “did all the work. Hopefully she had fun. We’re still together,” he smiles.

“I’m not the easiest person to read and get along with. People use the word stubborn. I try to use the word determined. But stubborn fits me. I have a belief and that’s the only way I know how to operate.”

Lancaster, McManus, Flutie, Osbaldiston and most of the Steeltown Grey Cup team are back for the 2000 season, and time will tell whether the system will continue to succeed. Chemistry in the locker room, focus on the game, throw in a struggle to add that spark, and you’ve got a winning team. Sounds Utopian, but Lancaster’s career—as player, coach and commentator— speaks for itself. For now, there’s no time to contemplate the past.

“The one thing I hope, when [the guys] walk away from it is that they remember the times in the locker room, on the buses, the fun, ‘cause that’s what it’s all about. When they get all done with this game, I hope they never remember a practice. If they remember a practice, they’ve had a lousy career.”

Here’s betting the coach doesn’t remember any practices—not a practice, or a player who didn’t re-sign, or the last pass that went incomplete. There’s no point. It won’t help win the next game.