Milos Raonic

Game, Set, Milos.

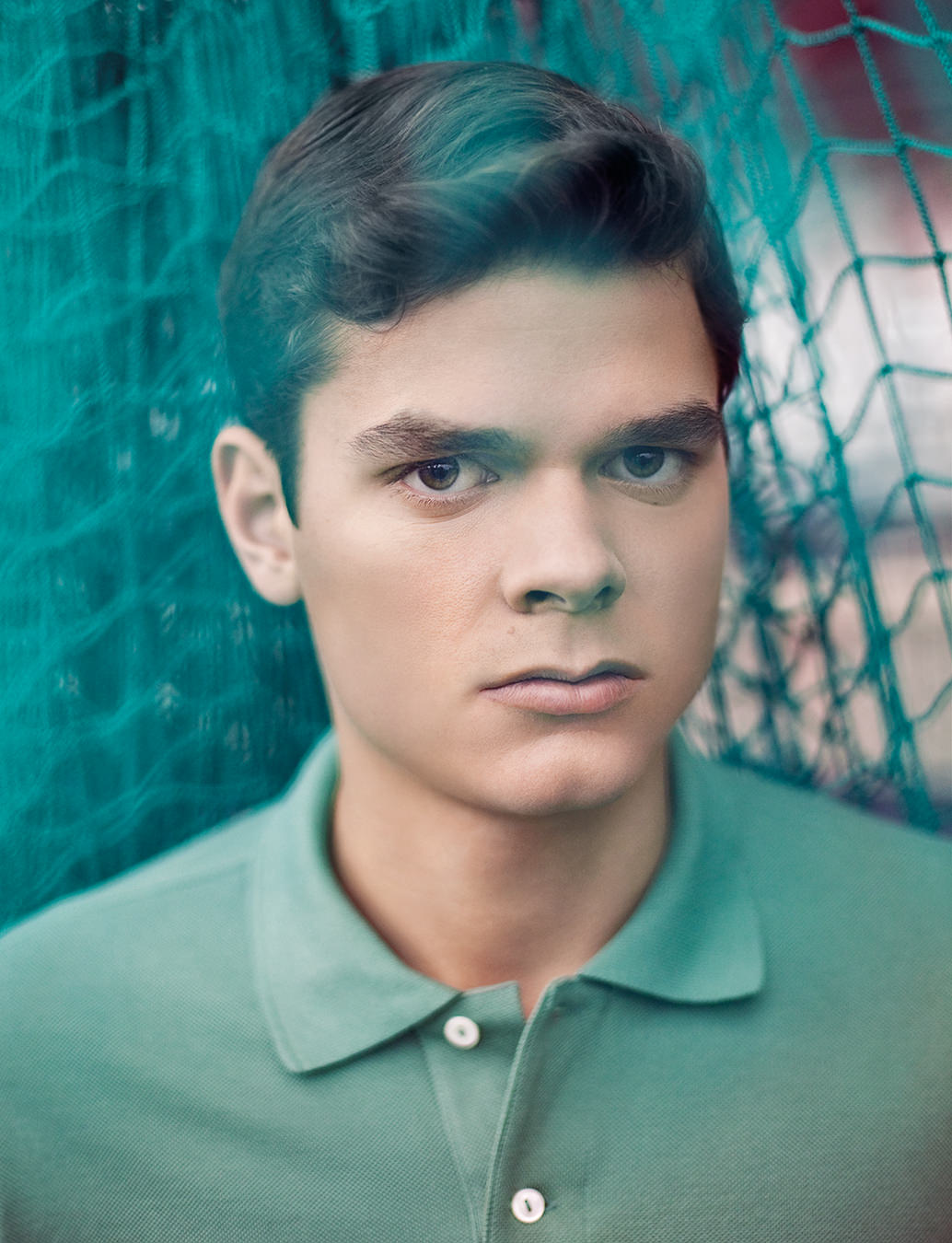

There is a lot that happens in the five milliseconds before Milos Raonic smashes his tennis racket against the ball he just tossed above his head. The head itself (with once wild, now professionally coiffed, hair) is locked back in rapt attention. Six thousand sets of eyes in the arena are focused on that little yellow ball, so it might be hovering by collective mind power. They are mainly the eyes of Canadian fans, as this branch of the Davis Cup is being played in Vancouver; and there is hope in their eyes, since the Canadian team, of which Raonic is undoubtedly the star, is far outmatched by their French adversaries. The Canadians have lost their first match, but Raonic is one point away from evening the score. Fully stretched to make the serve, his six-foot-five frame becomes a kind of bow—bent in a single, tense concave, and arcing from the top of his Wilson to the toes of his size-14 shoes. Even the drunken yahoos who have been calling to him like he’s their younger brother—“We love you, Milos!” “Milos, use the Force!”—have for this moment, at last, shut up. The world holds its breath.

Raonic has a serve that’s been clocked at 249 kilometres an hour—the second-fastest serve ever recorded in professional tennis. It’s easy to imagine it breaking bullet-style through his opponent’s racket altogether. Two hundred forty-nine kilometres an hour. For the record, that’s 80 kilometres an hour faster than the hardest slapshot ever taken in the NHL. This is only one element, though, in Raonic’s skill set, and he’ll tell you as much. “I have the weapons to win,” he says while we drive through a sun-dazzled downtown Vancouver. “It’s just a matter of learning how to use those weapons.” With his cracking voice and barely a beard to shave, it’s bizarre to imagine that this 21-year-old is now the greatest tennis star in Canada’s history. He is the 23rd-best player in the world. As we talk, his eyes graze up at the glass towers that slip by his window, and he leans perpetually forward in his seat, legs apart like a man on a jumping horse. Yet there’s no showmanship in his words at all; he speaks softly, if pointedly. What must it feel like to be barely able to order a beer in some parts of the world, but also know that you’re better at this one thing than nearly seven billion others?

Watching Raonic play, one is aware of a coolness, an almost Zenlike quality, which belies his youth. On the court he doesn’t grunt or bare his teeth the way his opponents do. He puts one in mind of a Jedi master, batting missiles away with his eyes closed. “I’m at my best,” he says, “when I have a serenity. So I work to not get fired up. Every time I get emotional, I make mistakes.” In fact, there’s a calmness about Raonic off the court, too. Like most men accustomed to being the tallest person in the room, he has a blameless mixture of confidence and shrugs. He doesn’t make much eye contact—when Raonic was interviewed after the Australian Open, the interviewer had to stop the camera at one point and ask the young champion to look him in the eyes, instead of staring straight into the lens. But that’s more a sign of Raonic’s careful speech than anything else. He has dropped the guffawing, anxious talk that most men his age employ. Does he meditate to achieve his rare calm? “No, but I bring a chair into the shower and sit under the water for an hour.”

Watching Raonic play, one is aware of a coolness, an almost Zenlike quality, which belies his youth.

The coolness is backed up, of course, by real—and relentless—work. It started at the age of eight, when a tennis club full of 12-year-olds wouldn’t let him in. Raonic worked against a ball machine from 7:00 to 8:30 a.m. every day before school, and then from 9:00 to 10:30 p.m. afterward until, six months later, the club let him in. Today he’s still usually the youngest, the upstart; the average player on the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) world’s top 100 list is five years older than Raonic. And though he’s already breached the top 30, he’s a year younger than anyone else in that bracket.

Statistically speaking, Raonic shouldn’t be anywhere on the ATP world rankings list at all. And not just because of his age, either. What makes Raonic a real anomaly is the country he calls home. Tennis players are from France, or Switzerland, or the USA, or Serbia, or Spain; they can be from Sweden or Germany or Ukraine. But Milos Raonic hails from Thornhill, Ontario, just north of Toronto, a place that has the same reputation for producing great tennis players as Iceland or Melanesia—which is to say, none. In fact, there is only one other Canadian on the ATP chart of the world’s top 100 players.

As though to mock hopeful nationalists, Raonic wasn’t actually born here—he was born in Montenegro. His parents (a pair of engineers) sought to disentangle themselves from the Yugoslav wars and brought their family to Canada when Raonic was three. In the comment feeds beneath YouTube videos of Raonic playing, it’s common to see fans arguing in heated tones about whether he “counts” as a real Canadian. “I know they say these things,” says Raonic (his voice has the slightest accent, thanks to Serbian-only conversation at home). “But that debate is just a buzz. I’ve never thought of playing for anyone but Canada.” In our entire afternoon together, this is the one time Raonic loses an ounce of calm. “It’s always the Canadian flag next to my name.” That flag will be especially prominent this summer, when Raonic joins the Canadian Olympic team in London, playing matches at the All England Lawn Tennis Club at Wimbledon from July 28 to August 5.

Like any Canadian kid, Raonic grew up playing street hockey, and he recently got giddy upon gaining admittance to the Toronto Maple Leafs’ locker room. Two Canadian teens have even composed “Milos Raonic” songs that idolize him and claim him as the saviour of Canadian tennis. And he does see his role as being partly an ambassador for a sport that’s often shuffled aside in this country. Hours before a press conference at the University of British Columbia, where the Davis Cup matches took place, Raonic turns to me and says, “You know they sold this event out—6,000 tickets—in 25 minutes? I think something’s happening here.”

Raonic may be determined to break into the top 20 bracket, and then the top 10, but he never actually looks at the rankings. “I might see something by accident on Twitter,” he explains, “so I’m vaguely aware.” If that sounds disingenuous, it’s only because most people don’t care about anything with the purity that Milos Raonic cares about tennis. Raonic was so anxious to get on with his real life, that he took extra classes online in order to graduate from high school two years early. When I ask him why he cancelled plans to attend the University of Virginia weeks before he was supposed to start there (on scholarship), he gives me one of his rare moments of eye contact: “Because. Tennis can’t be just part of your life. It’s your whole life.” (His parents were worried about the move at the time, but now that he’s brought in over $1.2-million in prize money, it’s hard to call it a misstep.)

During the off-season, Raonic puts in 10-hour days, filled with tennis, fitness, physiotherapy, and injury prevention (he had to bow out of 2011’s Wimbledon because of a hip injury in the first round). That drops to three-hour workouts during tournaments. Then there are the rituals, the superstitions, which are followed as faithfully as his workout regimen. The night before every game, a steak will be eaten; in the tennis bag, a stuffed pink pig must hide; his shorts are always black unless mandated otherwise; beneath those shorts, the same style of underwear is worn every game. Before a match, there will be no music, for fear that a song could get in his head and distract him on the court. He’ll move up and down the locker room for 30 minutes to get his heart rate up. There is no praying.

It’s a proven formula, and you don’t fiddle with rapid success. For Raonic in particular, things are rising fast and furious. He tweets daily to over 36,000 followers, with attached photos from soccer games in Madrid, gyms in Chennai, the sidewalks of Manhattan; he’s lunching in Monte Carlo, or he’s dining by the Yarra River. Aside from all that prize money, he’s garnered a Lacoste sponsorship and, most recently, a gig as the North American ambassador for Biotherm Homme (replacing “Mr. Big” from Sex and the City, Chris Noth). He’s been meeting his idols in hockey, basketball, and football—he’s much more star-struck by them than by movie stars. As he jets from city to city and is chauffeured from photo shoot to photo shoot, there’s only one party he hasn’t managed to get access to. “My mission this year is to get into a Victoria’s Secret runway show,” he says. “The women are just totally extraordinary. I keep pushing my manager to make this happen and it hasn’t yet.” When I commiserate, he asks me, “Could you put that in the article? It might help get me in.”

The eagerness about Victoria’s Secret is a reminder this is all rather new to Raonic. The speed of his climb has been as swift as his serve. On January 5, 2009, his ranking was 914th in the world. By January 2010, he’d jumped up to 370th. Then, just last year, he made the fateful leap to double digits. So interviews, five-star hotel rooms, and black-tie events have an impressive freshness to them. (As we wandered out of one Fairmont hotel, he asked me about the other Fairmont down the street: “Is it better than this one?”)

And it’s all a bit much. “I’m still a kid,” he says. “I still need to grow into everything.” He’s speaking about his life and his work at once. “I only have 60 matches under my belt and I’m playing people who have 300.”

Although he doesn’t have an exact timeline worked out, Raonic clearly sees all this as the prelude to his real, even grander career. You don’t get to number 23 without expecting to be number one. There’s a directness, a sense of destiny about it, when he moves, when he engages with people. Everything is where it should be and everything is moving toward its rightful place. And it is going to move right now. “Being stationary, even in an airplane, is very hard for me,” he says. “I spend all this time training myself to move, so being still now feels wrong.” Like his serve, his persona gives off a sense of being all-in, as though he’s constantly playing a tournament in his head from which it would be painful to take a break.

Watch him play and that attitude becomes animated. Every moment is the single moment of strength and beauty, where a hundred muscles—honed by a short lifetime of training—can work in concert to produce a single impact.

Back at the Davis Cup, Raonic has dominated the match. The Frenchman, Julien Benneteau, is about to lose his third consecutive set this afternoon. Raonic, for his part, looks calm, even graceful on the court. Is he even sweating? Look at that 21-year-old and you see a face galvanized by a particular, focused energy. His eyes—no, his body—locks onto the movement of that tossed ball.