Chef Colombe St-Pierre

Queen of the regions.

The district of Le Bic is about a 20-minute drive from the downtown core of Rimouski, the entry point for the Bas-Saint-Laurent region of Quebec. Renowned as one of the most beautiful villages in the province, Le Bic draws tourists year-round, outdoorsy types who paddle sea kayaks in summer and cross-country ski or snowshoe around the Parc national du Bic in winter.

However, Le Bic has also become a gastronomic destination, thanks primarily to a young woman by the name of Colombe St-Pierre. Montreal chef Charles-Antoine Crête refers to St-Pierre as “La reine des régions” (Queen of the Regions), and for good reason. Her restaurant Chez St-Pierre and her championing of local products have placed her hometown on the food lover’s map. And it’s a responsibility she’s taken on proudly.

Chez St-Pierre is a regional restaurant with big city sophistication.

St-Pierre’s story is worthy of a Hollywood small-town-girl-makes-it-big picture. The daughter of nearby Île Bicquette’s lighthouse keeper, St-Pierre, 39, lived on the island as a young girl until her father’s job was eliminated in 1992. “All of my summers were spent on that island,” she says. “And part of me comes from that time. I hold on to that image of the horizon. It’s important for me. I have no yesterday. It’s all about tomorrow.”

Her cooking influences are many, but don’t expect this self-taught chef to name any big culinary stars as mentors. Instead, she turns to family. “My dad was very cool, very cultured, and independent. He started gardening just to show us how we eat. We had chickens and pigs. When I brought eggs to school to colour them for Easter, they were brown, which you can’t dye,” she explains. “People teased me over it because it showed I came from the country.”

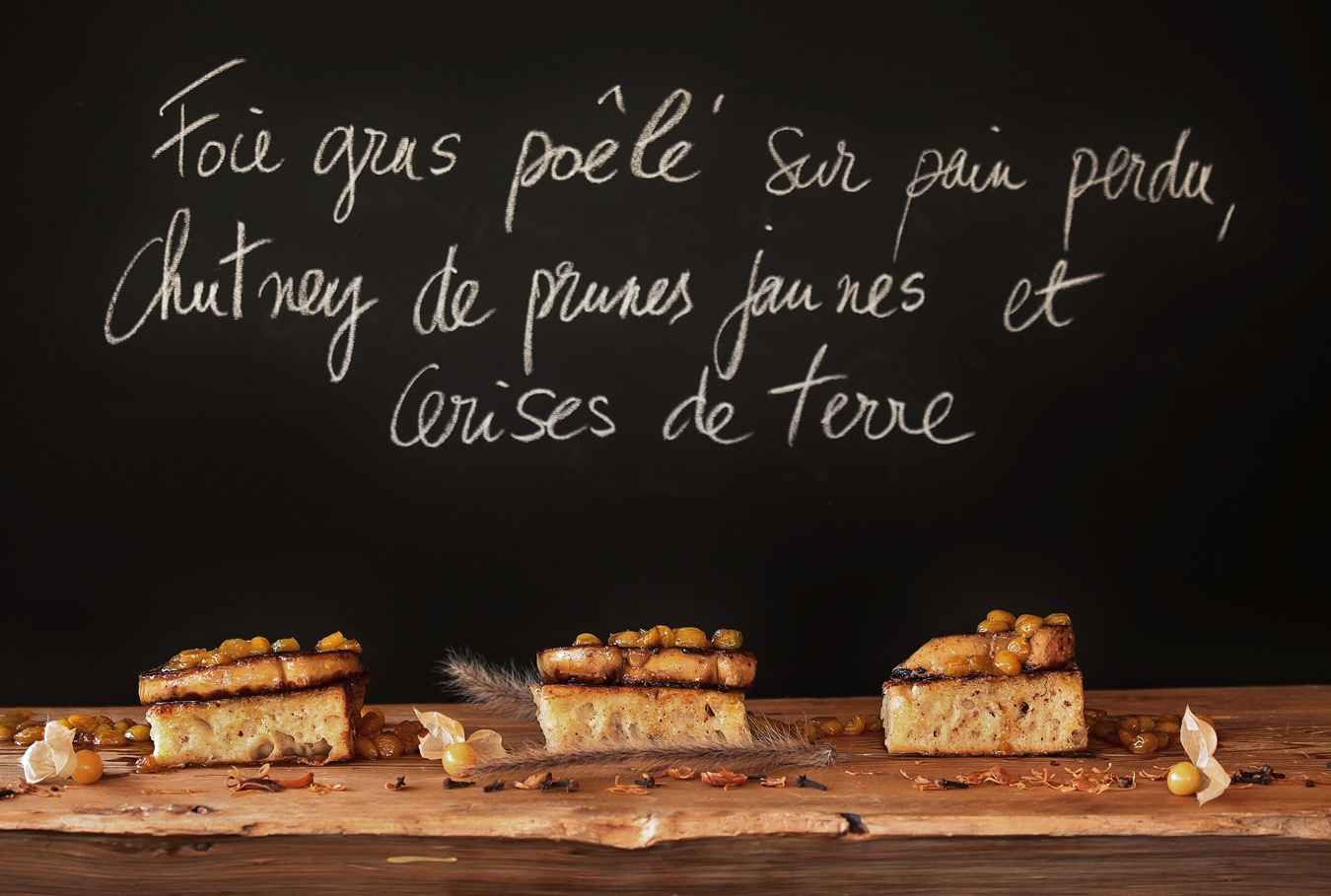

Pan-fried foie gras on French toast with plum and groundcherry chutney.

Despite the teasing, St-Pierre remembers her childhood as a happy one, filled with the many characters within her family. “My paternal grandmother opened the first French gastronomic restaurant in Rimouski,” she says. “Both my grandmothers were strong-willed women at a time that didn’t allow them to be.”

You can sense that family determination in St-Pierre’s personality. Her restaurant, located in the shadow of the grand Sainte-Cécile-du-Bic church in the town centre, occupies an unpretentious clapboard house. Her customer base reaches far beyond the local population of 3,000. Fans drive five hours from Montreal, or three from Quebec City, to savour St-Pierre’s cuisine. Her passion for featuring local ingredients, brought to her by her own personal forager, makes her menu hyperseasonal. Her plates include foraged ingredients like sea spinach, Scotch lovage, meadow salsify, and a wide array of seaweeds. There are dog rose and juniper berries, both green and navy blue when ripe, and plenty of wild mushrooms like ceps and chanterelles. She champions the local organic pork and beef, but snow crab is her favourite (“I fight to get it!” she says) as well as the little mackerels from the Gaspésie, of which she insists, “You must eat quickly because the flesh is so fragile.”

Her cooking influences are many, but don’t expect this self-taught chef to name any big culinary stars as mentors. Instead, she turns to family.

During dinner service at Chez St-Pierre, you can watch the chef in action, having a laugh with her sous-chef while plating the food. St-Pierre is a dynamic, self-confident woman with a great sense of humour, qualities all too rare on the professional cooking scene. “I received so much in my life that I felt like cooking was my way of giving back that love to as many people as I could at one time,” says St-Pierre. “Cooking is the gift of giving. It’s stronger than I am. It’s like a drug.”

Like countless chefs, financial need initially drew St-Pierre to the restaurant life. At 17, she was attending CEGEP in Montreal when she took a dishwashing job at a little bistro called La Marivaude. Besides washing up, she was given tasks like cleaning vegetables or plating desserts. Meanwhile at school, St-Pierre had changed her major three times, from science to communications to languages, still searching for her raison d’être.

Post La Marivaude, St-Pierre met a young man by the name of Patrick Piuze who opened Le Pinot Noir, a wine bar in Montreal. When the wine bar’s head chef left, St-Pierre was asked to take over. She was 19 years old. With little kitchen experience, St-Pierre says she felt like an imposter—until a restaurant reviewer sang her praises. “The critic said he saw something in me. More people had confidence in me than I had in myself. That motivated me. I started to devour cooking. I felt guilty, and I don’t know why, but it pushed me to read about the history of cooking. And I made my peace with that.”

“It’s not me who decides what to put on the menu, it’s the products that do the dictating,” she says.

St-Pierre also began to travel the world in a “quest for truth in cooking,” which lasted some eight years. “I went to Germany, Australia, South Africa, and Malaysia. I wanted to understand how it worked in each place.”

Then, St-Pierre contemplated her next move. “There’s an expression in French: ‘La poule naît au village, on la mange en ville’ (the chicken born in the village gets eaten in the city). I agree. So I came back home. I knew what was important to me was to revitalize my region. There’s work to be done here. To defend your territory, you have to live there and understand it. I’ve seen products here disappear. I’m seeing our crab, shrimp, seaweed all going to Asia. My mandate is to live in this region to develop our food heritage. Identity has always been a huge issue in Quebec. In the book Physiologie du goût, the famous French gourmet [Jean Anthelme] Brillat-Savarin said, ‘Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are.’ That’s the message I try to transmit in my cooking, with this magnificent setting all around me.”

“Cooking is the gift of giving. It’s stronger than I am. It’s like a drug,” says St-Pierre, whose menus feature seasonal ingredients procured by her own personal forager.

Dining at St-Pierre’s restaurant in this village overlooking the Lower St. Lawrence Estuary, with its capes, coves, and islands is a unique experience boosted by sea smells and the cries of seabirds. In these environs one is transported far from the busy restaurants of Quebec’s big cities. Yet when the food arrives, there is no denying its sophistication. “I work with what my forager brings me,” she says. “It’s not me who decides what to put on the menu, it’s the products that do the dictating.”

Menu items have included a soufflé of snow crab with crab salad, onion chips and Riopelle cheese mousse, as well as a scallop gravlax “mi-cuit” with wild pepper, clams, and a brandade enhanced with Alfred le Fermier cheese. For dessert—after cheese—how about the wild blueberry tart with basil sprouts, white chocolate and puffed rice tuile, juniper berry sorbet, and cranberry granita?

St-Pierre’s passion for local ingredients makes her menu hyperseasonal.

No doubt there are challenges to cooking in such an off-the-beaten-track destination. St-Pierre closes her restaurant from January to April, and lunch service stopped several years ago. The mother of three young children, St-Pierre has also curtailed her media activities to focus on the restaurant. As for her take on the endless questions regarding female chefs, she says, “I grew up with two brothers, so I’m a bit of a garçon manqué [tomboy], very much influenced by my masculine side. Professions like this one are more natural for a man. For women, the challenge is to stay in the profession. We’re competitive, but not in the same way. We don’t use the same tactics. We’re more gentle.”

St-Pierre was the only Canadian chef invited to participate in the Grand Gelinaz! Shuffle, in which the world’s top chefs cook in each other’s kitchens, and she has also attended the Parabere Forum, an independent international platform featuring women’s views and voices on major food issues. “When you work with small producers, you pay a price for products,” she says. “Some days, I can’t afford to buy halibut, so every time I eat it, I savour it like it’s my last, because products like that will disappear from our table. So we’re using fish heads instead. That’s where we are in Quebec—you do what you can with what you have.”

When asked how she would like Québécois cuisine—her cuisine—to be viewed in the increasingly international restaurant landscape, St-Pierre says, “What is the best way to present ourselves? To be real, who we are. Québécois cuisine must be in our image and what we are is bon vivant, the polar opposite of Michelin-style cooking. We must affirm ourselves in Quebec. We are accessible to everyone. That is the beauty of this part of the world, and that is what we must exploit. Ultimately, the meals that mark us the most are the meals that are the most authentic.”

Restaurant Chez Saint-Pierre, 129 Rue du Mont Saint Louis, Le Bic, QC G0L 1B0.

Food and restaurant photos provided by Chez St-Pierre.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.