-

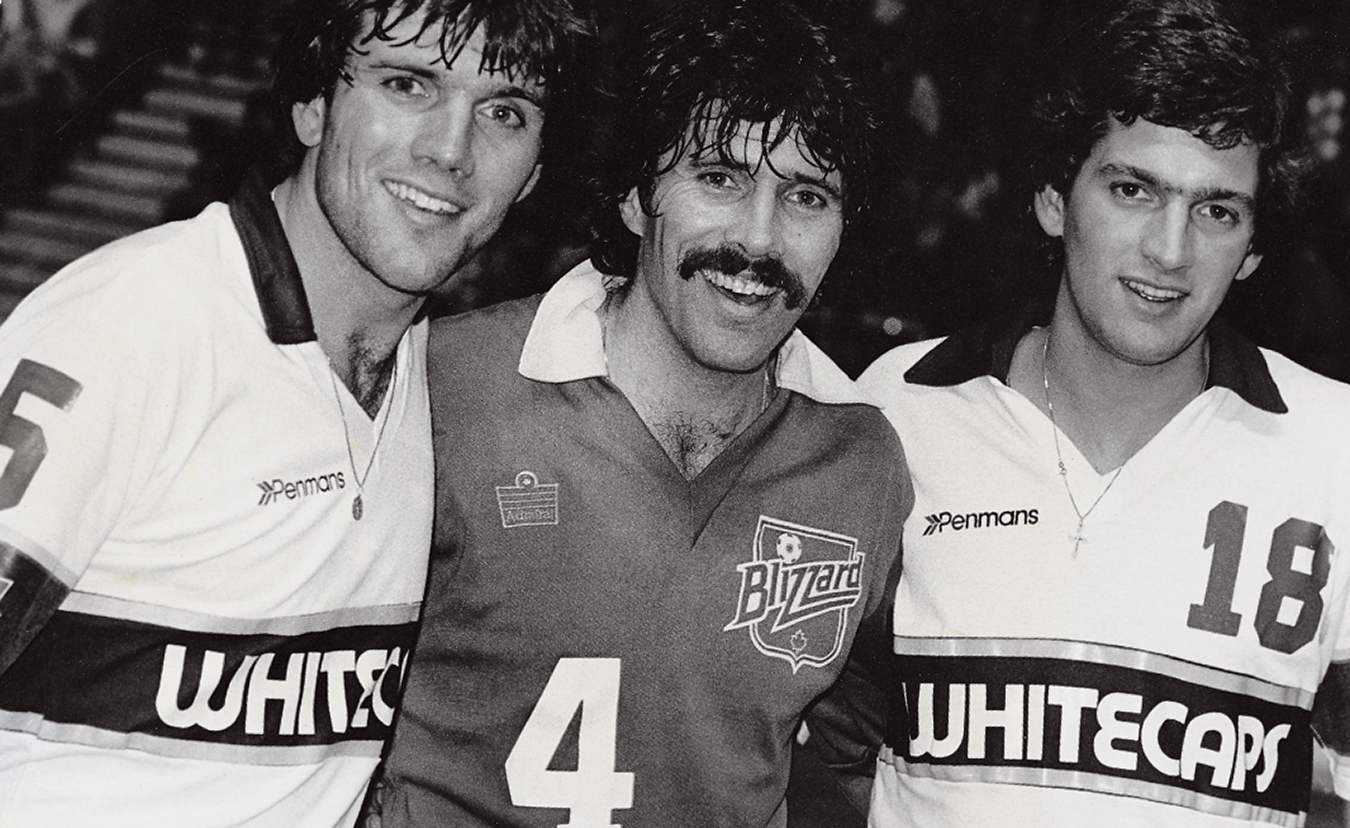

The Lenarduzzi brothers.

-

Celebrating a Whitecaps goal.

-

Wearing the colours for Canada’s national team.

-

The 86’ers win the CSL championship.

Backyard Ball to World Cup

Canadian soccer from the grass roots up, from someone who has seen it all.

We were in the tunnel leading into the stadium, doing a few warm-ups. It seemed normal, with the other team also there, waiting for the game. But I glanced over to my left and thought ‘Hey, that’s Platini! And there’s Le Roux, and Papin, and that’s Tigana.’ We were about to get out there in front of nearly 70,000 people and play against the French, against these legendary players, in a World Cup match.”

It was Canada’s first-ever such match, and Bobby Lenarduzzi was one of the Canadian side. “I was a fan, basically, but then you have to pinch yourself, because you have to go out against these guys and compete. As it turned out, we only lost 1-0, in the eightieth minute.” That team, which participated in the 1986 World Cup tournament in Mexico, lost 3-0 to Hungary: “We thought we could win, but got a little ahead of ourselves, didn’t play scared”, and failed to register a goal in the tournament. But this was the pinnacle for Canada at the most elite soccer level. “Today, virtually everything has to go our way, like it did in ‘86, just to qualify. Back then we had a thriving professional league in North America, and the Vancouver Whitecaps were league championship calibre. So not only were there great players, but a lot of competition at the elite level.”

Canadians should not assume this is a level playing field in the normal soccer scheme of things. “It was a confluence of things going well, for us to get to the World Cup. In normal times, we are on the fringe of our division. Even the big fish, Mexico, is a little fish in the pond of established countries, and then there are the established superpowers.” Every qualifying round is a quantum leap in the level of competition, so to go all the way is a huge challenge in itself, let alone how well you might perform at the big tournament.

“It’s about the delivery system. You can blame the national team coach, and I was the coach for awhile, so I know how that goes, but really it’s about the competition. Germany, England, Italy, France, all have club team and pro team systems, and an elaborate scouting system. It is if anything even more systematic than what the NHL does for hockey players here in Canada. Scouts identify kids at nine or ten years of age, and bring them into their system. So these young standout players enter into an elite competition even at that age, so that by the time they are ready to sign with a professional club team, they are experienced at a very high competition level. Their game has been in radical development for ten years already. The biggest difference is in the sheer speed of play, both mentally and physically. Players do things much faster, but the play evolves much faster as well. The combination really takes out the inferior teams in a hurry. At the World Cup level, it is nearly unheard of that an unheralded team that has not competed significantly at that level will do anything at all for the tournament. I can think of Cameroon a few years back as one exception, but basically it never happens.”

Big-time soccer, though, is just as valid now as it ever has been. “I still believe in professional clubs in North America, even if the best players are committed to play for other countries at World Cup time. It is like the Olympics: once you perform for one country internationally, you can only play for that country the rest of your career. So, great young Canadian players, for example, who sign with a European club team, will be under great pressure to play internationally for the nation whose club they belong to. They may not even be released by the club to play for Canada.”

It is all about role models, and showing younger, would-be players that the game has something substantial to offer them in return for their own commitment to it. “For example, when the Whitecaps folded in 1984, there were 45,000 kids registered in soccer leagues around the country. A year later it was 27,000. That can’t be a coincidence. The existence of pro teams, I think, influences the interest kids have in the game. And I know Toronto, for example, is a fantastic soccer city, at every level. So are Montreal and Vancouver.”

This is not to undermine the game in its fundamental glory at all. “For Canada, the sport is doing fantastically well at the recreational level. The game has changed dramatically, in that it encompasses psychology and nutrition in a way it never used to, and for kids it has such a great capacity to enhance self-esteem. And, at the grass roots, women’s soccer is growing exponentially. And it is excellent soccer. Then there are co-ed teams, teams put together at work, so the game is alive and well at virtually every level in Canada.

It is all about role models, and showing younger, would-be players that the game has something substantial to offer them in return for their own commitment to it.

“The exception is for those 1-2% of elite players. If the mandate is to produce players to perform at World Cup levels, then we need to go back to the drawing board. We cannot realistically compete on that level. At the elite levels, everyone’s trying to do the right thing in Canada, but I suppose it boils down to a uniform approach, a system for development, that might yield some elite players. Still, without the steady competition, its tough.”

For this year’s World Cup, Bobby will be in Toronto, at the CBC studios, doing game analysis from direct video feeds. “It’s not nearly the same as being there, and I can always tell when a hockey telecast is being done from a feed as opposed to the rink. Ryan Walter is truly one of the best at making it seem real. So, I’ll give it my best shot. The tournament is always fantastic. For North Americans, it would be as if any one of the major pro sports were played around the whole world, and a tournament took place every four years to determine a true world champion. Soccer is the only such major professional sport to do it, and it is an amazing competition.”

Bobby spends the majority of his time these days running training camps and seminars for young students and aspirants of the game. It is still a great pleasure to be associated with the sport that he has excelled at in every way possible for a long time now. “I was in Salt Lake City recently, and someone came up to me in the lobby. He said he was in Grade 2, and I had come in to give a talk about professional sport, about dedication, responsibility and teamwork, things you can use your whole life. He said it made a big impact on him even though he didn’t even play soccer. I still get a kick from hearing that, and from watching the young players develop.”

Bobby shows all the marks of a fine professional athlete, even as he approaches the early stages of middle age. He maintains the boyish good looks, no grey hair, and his frame is not supporting more than its share of body weight. There is a spring in his step, whether in track suit or in business attire, and folks in the local coffee shop recognize him and appreciate his easy manner. This summer, you can catch Bobby’s infectious love for and knowledge of the game as the drama, intrigue and glory of World Cup 2002 unfolds. As he drives away in his vehicle, the back loaded with soccer balls, he waves, and says, “whatever else I can say, its about keeping the kids playing, year after year. It’s a great game.”