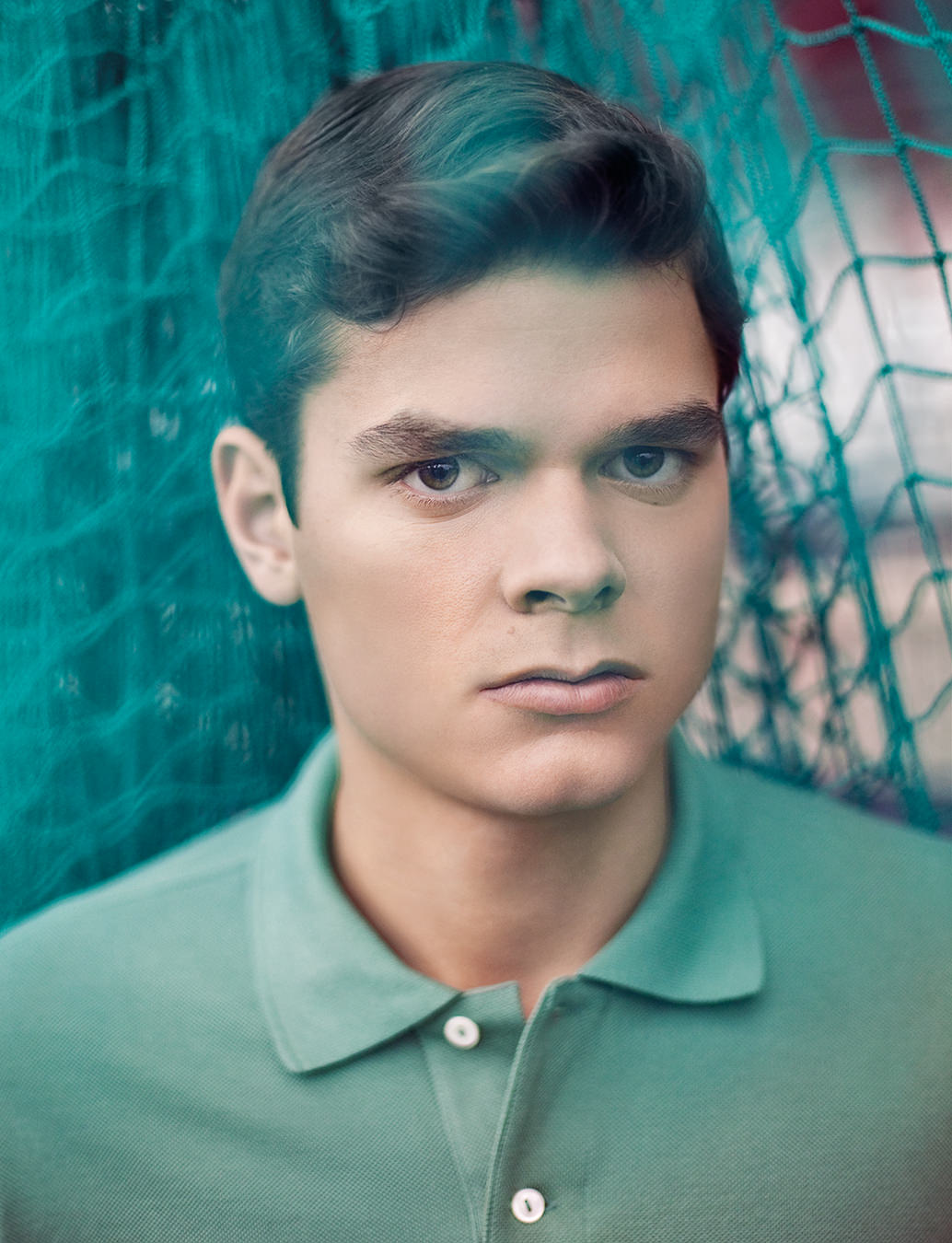

Nacho Figueras

Polo man.

Every sport has a star who, both in and out of competition, comes to embody the character and personality of the sport itself. For polo, that athlete is Ignacio “Nacho” Figueras. He is one of the leading players on the field today and certainly the most famous. He stands as the latest incarnation of the dashing Argentine polo player, an archetype that has a long history. And Figueras has quite possibly done more than any other competitor to raise awareness of the sport.

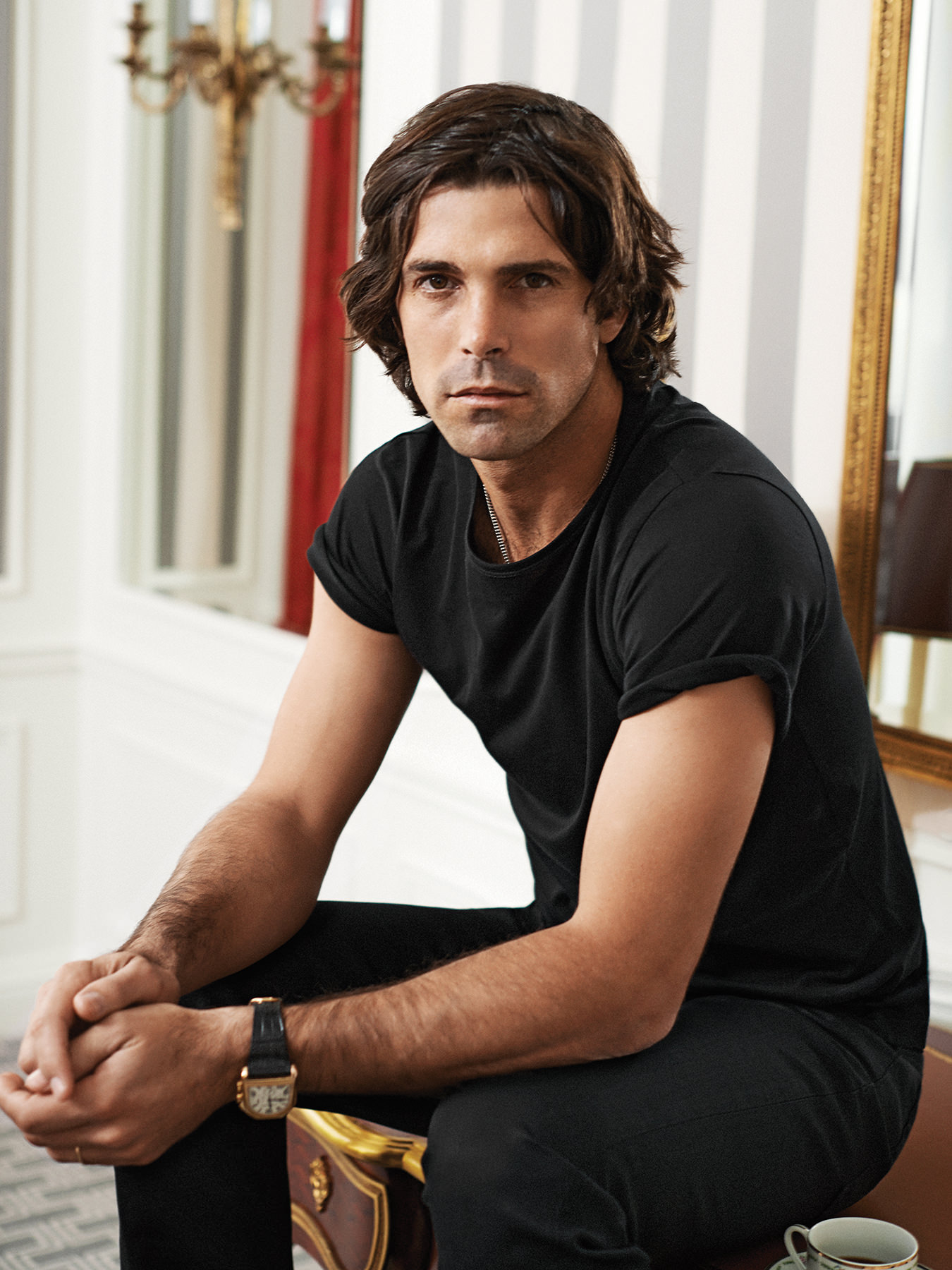

“Nobody’s really Argentinian,” says Figueras, our conversation in the Cognac Room of the St. Regis New York on a day off from competition. “Four or five generations back, I’m Spanish.” With a hero’s jawline, the 36-year-old grabs the attention of flashing cameras. People can’t get enough of him, and fans are thrilled to brush cheeks with the face that has starred in countless Ralph Lauren advertisements. Tall, dark, and handsome definitely applies to Figueras. Although he’s not one to admit to it. “To me, the most important thing is the inside, so I don’t pay attention to the outside,” he says as his chestnut hair flops beguilingly across his face. “Attitude—that’s what I’m focused on.”

Popularizing polo is the challenge for Figueras. And although the sport hasn’t erased its public image as a rich man’s game, that is a misconception that Figueras has spent much of his career trying to correct. “I understand where the elite thing comes from, obviously, because polo is associated with Prince Charles and Prince Harry,” he says. “Polo is a sport that you pass from generation to generation. Today, playing polo, logistically, is a bit more complicated and expensive, but in the beginning of the [last] century, horses were around. We didn’t have cars. We had horses. And if you had a horse, you grabbed a mallet, and you played polo.”

How do you persuade North Americans to watch men with mallets ride horses? Figueras, a 6-handicap player (which places him in the top 5 per cent of players in the world), is suited to the task. “I do believe there is a little space for polo,” he says. “And if I can widen that space…” He trails off, and then adds, matter-of-factly, “Polo will never be basketball or [American] football, but there is room to grow.”

Nacho Figueras wears Ralph Lauren.

The eldest of three children, Figueras was born in Buenos Aires in 1977 to an agriculturist father and a homemaker mother. He started playing polo at the age of nine. “My father bought a farm next to his best friend’s farm, whose entire family played polo, and we started going out to the farm on the weekends,” he says. “His friend had a son [fellow polo player Lucas Monteverde] exactly the same age, and we kind of grew up together. Many people ride in Argentina, it’s not that unusual. Every weekend, I played polo.” Figueras turned pro at 17, playing in Paris from 1994 to 1996. Right after Paris, he played in the United States, “in Columbus, Georgia—the middle of nowhere. I didn’t bring polo anywhere there,” he says with a grin. He went back to Europe for a couple more years. In 1999, he went to the Hamptons for the first time and played at the Bridgehampton Polo Club. And that’s when he stepped into the spotlight.

Figueras began modelling for Ralph Lauren in 2000 after meeting photographer Bruce Weber at a dinner hosted by Kelly Klein (ex-wife of Calvin) in the Hamptons. Weber introduced Figueras to Lauren. Figueras has been under contract since 2005. The outline of the polo star on horseback for Ralph Lauren’s logo was as fitting as it was a clever marketing strategy. His duties have since expanded to being an ambassador for the brand and the face of several of the company’s fragrances. “The fact that I was doing things with Ralph gave me a little bit of attention, and I said [to myself], this is a great opportunity to talk about polo,” says Figueras.

While Figueras may not have the vast scope of David Beckham, they share some commonalities. Both are fine specimens. Both have noteworthy wives (Figueras’s wife, Delfina Blaquier, is a photographer and fellow model for the Ralph Lauren Romance fragrance). Both have four children. Both hobnob with celebrities. And both have tried to raise the profile of their sports.

After Beckham’s five-year tenure in Los Angeles with the LA Galaxy soccer team, that he had an impact is undeniable. Skeptics say that Beckham’s mission was unsuccessful, citing poor television ratings and the fact that soccer has yet to become mainstream. But that is an unrealistic expectation; soccer becoming mainstream was never going to happen within five or even 10 years. And yet a recent ESPN Sports Poll pronounced soccer as America’s second-most popular sport for those aged 12 to 24 (the very age group that grew up with Beckham playing in the United States), outstripping the NBA, MLB, and college football. Could one man similarly determine the future of polo in America?

“After my family, polo is my life. All day. I wake up thinking about polo. I read polo. I eat polo. Where are the horses? Is there a match tomorrow? Where’s my wife and my four kids? And everything else is horses and polo,” says Figueras.

The admiration for Figueras has been a boon to the polo world. His current team, Black Watch (co-owned with Neil Hirsch, and a commercial sponsorship with Ralph Lauren on the apparel), is one of the most skillful of the set. He’s also been granted additional platforms to spread the sporting word about polo via events such as the Veuve Clicquot Polo Classic and through his role as a “St. Regis Connoisseur” for the company’s polo program.

St. Regis Hotels & Resorts has long been associated with the world of polo through its founder, John Jacob Astor. Mrs. Astor also played a part—the Mrs. Astor, who was the undisputed grande dame of American high society. She was known to host lavish balls, including those at the St. Regis New York when it debuted in 1904, and many polo players and spectators were there. “The Astors used to attend polo matches and hosted the polo players in the hotel here,” says Figueras. “How can we bring these times back?”

Polo matches on Governors Island, off the coast of Manhattan, were highlights of the New York social scene at the turn of the 20th century, just a few decades after polo came to the United States. (In 1876, fascinated by polo on a trip to England, James Gordon Bennett Jr. introduced the sport in New York.) It proved even more popular at the end of the First World War, when the U.S. Army adopted polo as a major activity, promoting its contribution to physical fitness, teamwork, and combativeness. Indoor riding armouries were constructed throughout the country. The Polo Ball became an annual social event during the 1920s. But during the Second World War, polo was removed from the Olympic Games, and horses were returned to military posts and sent to duty.

Nacho Figueras wears Ralph Lauren.

It wasn’t until 2007 that the association between St. Regis and the sport of polo was revived with summer celebrations at the Bridgehampton Polo Club. The following year, the creators of the Manhattan Polo Classic, sponsored by Veuve Clicquot, invited the St. Regis to participate as a founding partner in the first match on Governors Island in almost 70 years. It was here that the St. Regis was introduced to Figueras. The following year, the St. Regis International Cup was established in England, and soon after, the St. Regis was invited to participate in polo charity events including those pitting Prince Harry of Wales and his Sentebale team against Figueras’s Black Watch. Nacho Figueras became the first St. Regis Connoisseur in 2010.

“What I bring is, I am the polo player,” says the Argentinian, discussing his collaboration with the storied hotel company. St. Regis has a hotel portfolio of 31 properties globally, and it hosts plenty of polo events; the balance of this year will see matches in Beijing and Abu Dhabi. “The history is there. It’s about putting it back on people’s agenda,” he says.

Polo is crucially different from other sports in one way: each team requires eight athletes, four of whom cannot speak the other four’s language, yet each must have unconditional trust in the other’s abilities. It is a natural ability, but it is honed from many hours of training, practice, and nurturing. That applies to both horse and rider. What separates a good polo player from a not-so-good one is “riding, riding, and riding, all day long,” says Figueras, “to the point where you get to know your horse almost as much as you know yourself. Knowing what he eats, what he does, when he sleeps, how much he exercises, how long it is going to take him to stop, how much he is going to turn, how much he is going to everything.”

Finesse comes after. “Some [polo players] are better than others with the ball, some have a better eye, some hit the ball harder, not so hard, better at defence—but everybody is an amazing rider. You have to be a great rider. Your finesse makes you this type or another type of player, but if you don’t ride amazingly well—no chance.”

It is thrilling to experience the speed (up to 65 kilometres an hour) and drama of the sport. No matter whether the spectator is an equine expert or novice, there is an instant captivation the moment you hear a horse’s hoofs thunder and a player’s mallet crack the ball. You feel the immense power even at a trot, but at a canter, it is profound. There is something primal about the experience.

Figueras has broken his nose twice, as well as broken his wrist and his ankle. He has been knocked unconscious twice from falling, he has stitches from being hit by a ball to the eye, and this past May, he had to sit out 12 weeks with a fractured acetabulum (the surface of the pelvis where the hip bone sits). “You can’t play polo if you think about accidents,” he says. “You can’t, because it’s going to happen. It can happen any second.”

There’s more than a little truth to the saying that there are only two ways out of polo: death or bankruptcy. Teams are funded by wealthy patrons, because paying for a string of ponies along with their grooms and farriers, vet bills, and stabling is a fast way to dismantle a fortune.

More than any other sport—even the world of Formula One—polo has earned itself the label Sport of Kings. Princes William and Harry are keen players (the latter’s Sentebale charity organization aids orphans and at-risk children in the country of Lesotho). The relationship between Figueras and Harry has evolved from playing numerous matches against one another, to the extent that the Prince knighted Figueras as a Polo Prince, an ambassadorial role for Sentebale. And earlier this year Harry wrapped up his whirlwind U.S. tour with a charity polo match, the Sentebale Royal Salute Polo Cup, against Figueras, who captained the St. Regis polo team, at Peter Brant’s Greenwich Polo Club in Connecticut. Afterward, it was hard to determine if the attendees were more taken by the presence of the handsome prince or the handsome polo player.

Nacho Figueras wears Ralph Lauren.

Home for Figueras is a ranch near Buenos Aires, where he has about 450 horses. “When I was young, it was all about winning and fighting in the good sense of the word,” says Figueras. “As you grow up, you start collecting and buying the good horses you like. Then what happens is that when all the great horses you bought start getting old, you start breeding them.” Considering that a top polo pony can fetch a quarter-of-a-million dollars at auction, Figueras has clearly come a long way from the boy riding a single pony. And he credits the modelling—even if he feels uncomfortable with the notion that he is indeed a model—as placing him in a “good position to bring polo to people.”

In his quiet elegance, Figueras wants to change polo in a similar manner to what’s happened to golf: rework its old image as a pastime for the crowd of white-gloved socialites played behind the gates of private clubs. “Golf, I believe 50 or 60 years ago, was very elitist. You had to be a member of a club, you had to dress [appropriately], it was very expensive,” says Figueras. “Now you have public courses, and you can buy a cheap golf club in Kmart for $9.”

Figueras’s rise to the top suggests that polo can be more democratic. In trying to bring polo to a new generation, he started with his own children. Hilario, 13, the eldest, has shown a keen interest in the sport. When Figueras was sidelined with the fractured acetabulum, Hilario made his debut at the sixth annual Veuve Clicquot Polo Classic this past June. “I love polo and I love horses—this is great. How can it get better? You start playing with your son and it gets better,” says Figueras.

He may have played on his father’s farm as a child, but today, Figueras is playing with princes. His dedication to the sport is tireless. And whether the masses become fans of polo or of Nacho himself, it’s clear that both are flourishing.

From Autumn 2013. Styling by Moses Moreno for See Management. Grooming by Tamah Krinsky for the Wall Group. Photographed at the St. Regis New York.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.