-

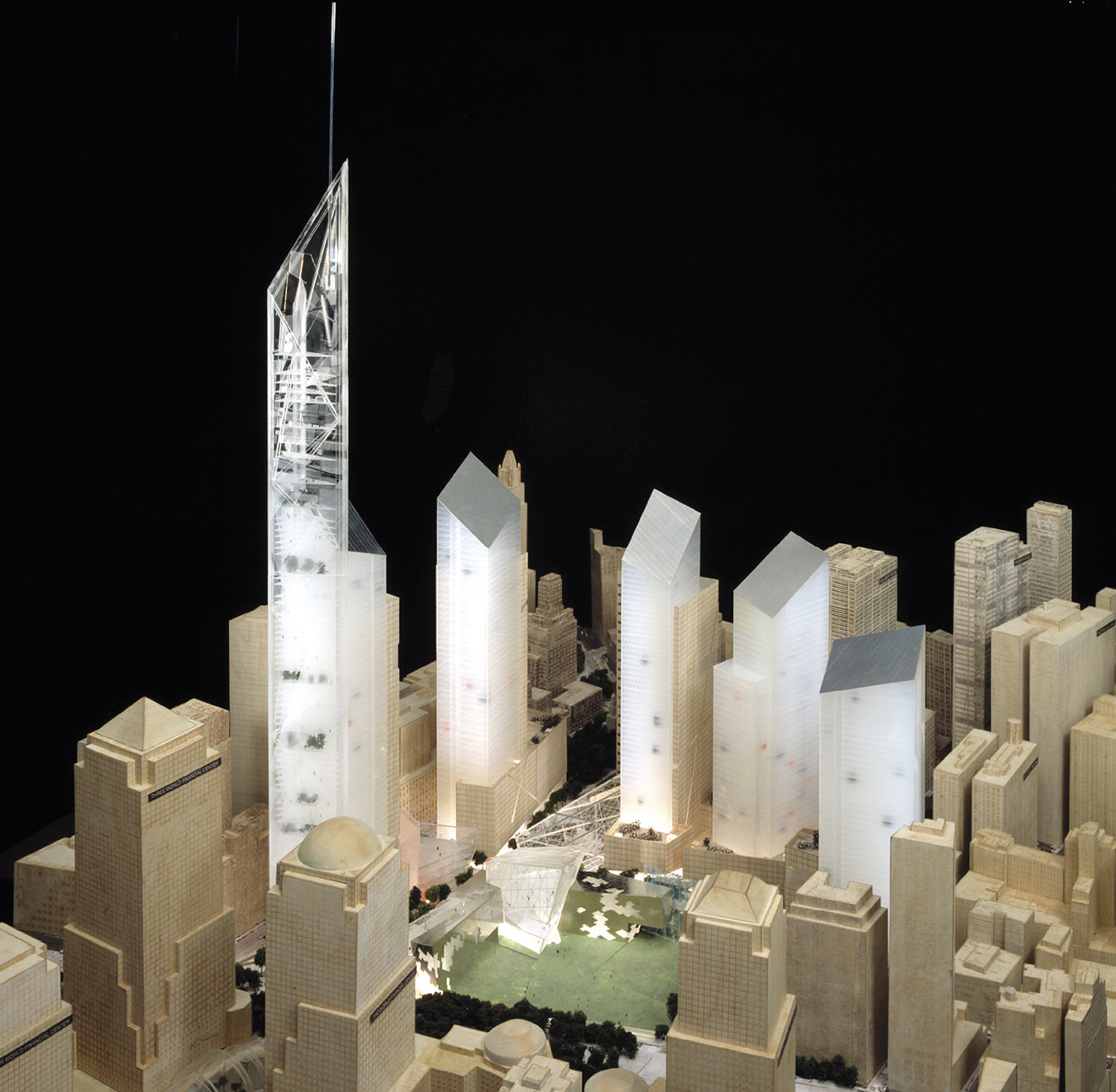

Lower Manhattan Station. Photo ©Miller Hare.

-

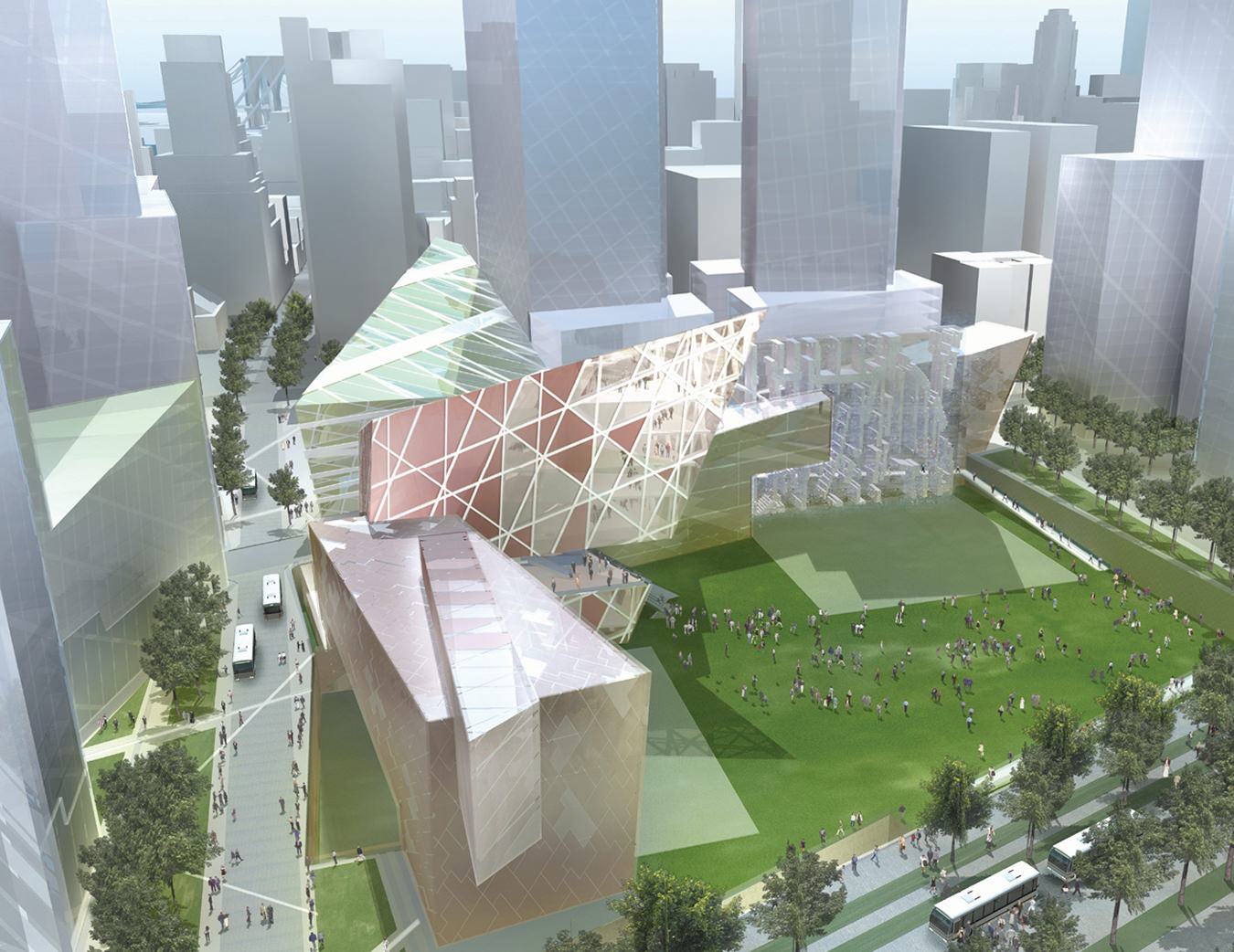

Aerial view of the Financial Centre. Photo ©Jock Pottle.

-

Financial Centre view. Photo ©Archimation.

-

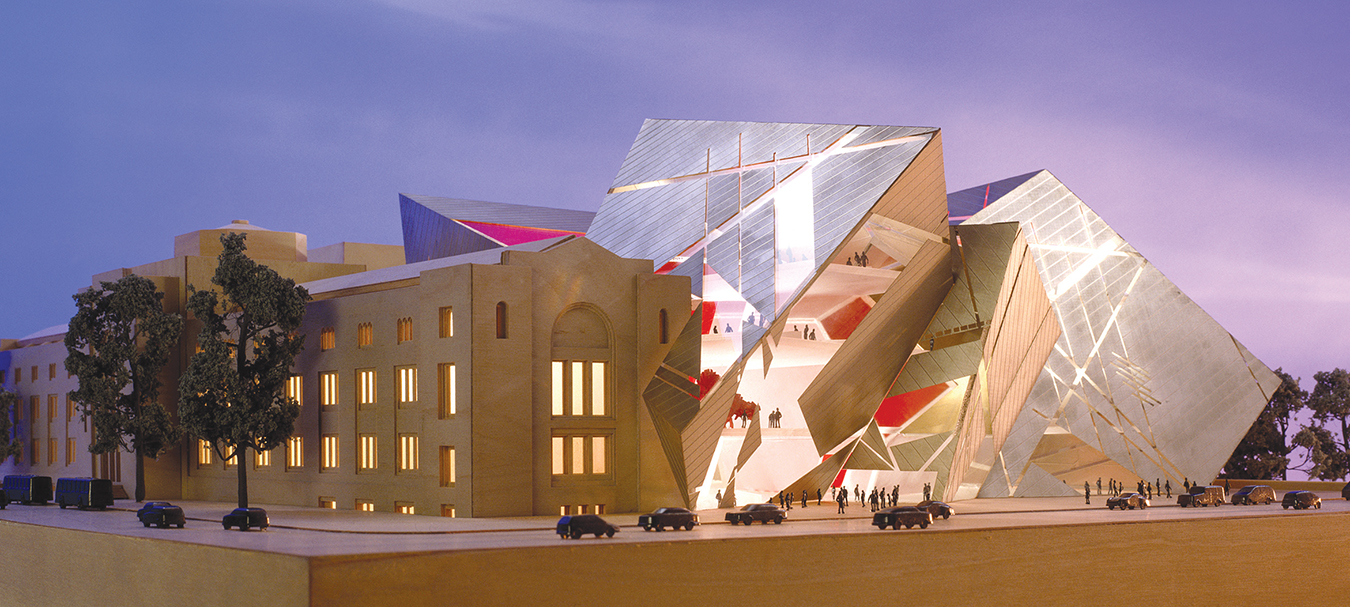

Michael A. Lee-Chin Crystal, north east corner ground level view of ROM. Lenscape Incorporated ©2003. Photo courtesy of The ROM, all rights reserved.

-

Aerial view of the ROM. Lenscape Incorporated ©2003. Photo courtesy of The ROM, all rights reserved.

The Structures of Culture

Daniel Libeskind, the ROM, and the World Trade Centre.

Architects of a certain tier, even in the early, shell-shocked days after September 11, even as fumes and ashes and wreckage still blanketed the unspeakably violated New York City site, were thinking forward. Something would have to be built to replace that which had fallen; whatever it was, the virtually immediate consensus within the design community was that the remaking of Ground Zero would be nothing less than the “project of the century.” No matter that when the commission finally was awarded last February, the century had barely begun and the architecture required to shelter a suddenly different world was unknowable as never before.

Almost to a person, the design elite vied for the job of master planning the 16-acre World Trade Center site, a $10-billion reconstruction enterprise that promises to take upwards of two decades to complete. The prospect of replacing the twin towers has put New York City on the international architectural map, a position it had in recent years ceded to cities like Los Angeles (Richard Meier’s Getty Center) and Bilbao, Spain (Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum). Helping to shift focus away from the anguish of the precipitating event was the fact that Manhattan was now charged with erecting the world’s most symbolic building.

With a highly controversial scheme, architect Daniel Libeskind, the diminutive, scholarly outsider, beat out the considerable competition. At 57, the Polish-born architect is considered a young practitioner (Frank Lloyd Wright created some of his most important work in his 80s and 90s). He has multiple projects in various states of design and construction worldwide (among them the Royal Ontario Museum’s Renaissance ROM in Toronto). And yet it is a certainty that Ground Zero is the commission for which Libeskind will forever be most known, and most accountable.

The main feature of Libeskind’s World Trade Center design is the Freedom Tower, a soaring, stylized paean to the Statue of Liberty. Extending the salute to his adopted country (some say capitalizing on the kitsch of full-throttle patriotism), the tower’s height is 1,776 feet: the year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence from Britain being the signifying date in American history. If built at this elevation, the tower and spire would become the tallest skyscraper in the world.

Other elements of Libeskind’s plan are the Heroes Walk, which traces the route of the firemen as they marched toward their fate, and the Wedge of Light, a piazza shaped by the angles of the sun between 8:46 a.m., the moment the first plane hit the north tower, and 10:28 a.m., when the second tower fell, and which would render the site shadowless during that precise period every September 11.

Also planned are a Memorial Museum and a below-ground Memorial Garden, two cultural centres, retail establishments and a train station. Even before the winning scheme was selected, the public debate over each facet of each design was protracted and passionate, and interest in the project has only increased as design development gears up. Already, for instance, there’s a push to put the Memorial Garden at the more accessible street level, with Libeskind having signaled his willingness to modify this and other parts of the plan. Growing groups of victim families are protesting the layering of anything commercial atop what they view as sacred ground.

But what has prompted the most fevered civic debate is the architect’s intention to keep exposed the 552-foot-long, 70-foot-deep structural pit that barricades Lower Manhattan from the Hudson River to the west. Despite it being graphic proof that the attacks didn’t do all the damage they might have, the massive, fenced-off crater is considered an unnecessarily brutalistic scar on the otherwise altered urban landscape. The New York Times railed against its inclusion in the winning scheme (“astonishingly tasteless”), and Libeskind now concedes that this huge area he imagined as strikingly evocative has struck the wrong chord and must at least be made considerably shallower. He stands by his original idea, though, which was to contrast the light-filled tower with the dark bog at its opposite end. “It’s important to embrace the reality of the terrorist act, not bury it,” he explains. “You can’t say nothing happened there.”

Controversy, emotion and the give and take of modern politics are prime components of Libeskind’s architectural practice. Much of it (although in the works are a private atelier gallery in Mallorca, Spain; a department store in Dresden, Germany; the largest European shopping center outside Bern, Switzerland; the extension to the Denver Art Museum in Colorado) involves memorials and monuments. “I bring my experiences in very conscious ways to all the projects I’ve done,” he says. “My work isn’t immune to deeper things. My mind is occupied by a number of images: Churchill speaking of conflict as one of the dimensions of world stability, my own memory of breaking the glass on Stalin’s portrait when I was in the third grade during the Polish uprising of 1956, the unimaginable hole where the World Trade Center used to stand.

“An architect is not some private person, making his design and then saying, ‘Take it or leave it.’ An architect is a citizen first of all. It’s not just about making models: one has to navigate through all of the conflicting desires that make New York what it is, and then, like Odysseus, somehow get home to the original vision.”

Born in postwar Lodz, Poland, to Holocaust-survivor parents, Libeskind moved as an 11-year old to Israel before immigrating to the United States in 1959 (he obtained U.S. citizenship in 1965). He was a child prodigy in music, a virtuoso accordionist, who eventually took a postgraduate degree in the history and theory of architecture at Essex University in the U.K. Libeskind’s lookalike wife (same slight build, short-cropped gray hair, designer glasses, black wardrobe) and business partner, Nina, is a native Canadian he met at a summer camp for children of the Holocaust.

Libeskind the academic (at 32, he was appointed head of the school of architecture at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan) began his practice dealing in theorems and abstractions rather than actual commissions. Not even a “paper architect” (the somewhat derisive term applied to those whose best-known work is beautifully sketched but unrealized), his early renown was based on his metaphor-laden treatises and critiques, as well as a series of complex drawings referencing everything from art to music to science.

The Jewish Museum Berlin, begun in 1989 and completed more than a decade later (“through seven governments, six name changes, five senators of culture, four museum directors, three window companies, two sides of a wall, one unification and zero regret,” he notes), was Libeskind’s first built structure. A zinc-coated, labyrinthine structure of angled walls and voids, the Museum was designed to mark the silence and emptiness left by the Holocaust. “It was an unprecedented task,” says Libeskind. “A monument of shame, not honouring anyone; a monument not celebrating anything.”

Celebrating, however, the opposite face of human endeavour is Libeskind’s transformation of the Royal Ontario Museum’s Renaissance ROM in Toronto. Out of a field of 50 international firms considered for the project, Libeskind was selected over the other finalists, Andrea Bruno of Turino, Italy, and Bing Thom Architects of Vancouver, to transform Renaissance ROM’s fortress-like mien into a dynamic city presence.

Libeskind calls his design The Crystal, after the crystalline pieces in Renaissance ROM’s noted mineralogy galleries. Correspondingly, the structure will be composed of organically interlocking prismatic forms. The architect’s intent is to turn the entire museum complex into a “luminous beacon and showcase of people, events and objects.” A sculptural composition of architectural elements at the entrance is set to enhance the vitality of Bloor Street. Proceeding from there, Libeskind has designed a vast atrium where intertwining stairs lead to the exhibition spaces.

Renaissance ROM, the fifth largest museum in North America with an inventory of nearly five million objects, will be completed in two stages of construction through 2006. For this architect so personally steeped in the arts, it is a vital counterpoint to signature buildings emerging from loss and destruction (aside from the World Trade Center project, his Jewish Museums for Copenhagen, nearing completion, and San Francisco, awaiting funding, are garnering much attention). Libeskind sees architecture as the physical embodiment of the world, for good or bad. “Architecture is a movement beyond the material,” he concludes. “It is length, height and width, but also the depth of aspiration and memory. The living source of architecture is the very substance of the soul and constitutes the structure of culture itself.”