-

Anna Hu, a cellist turned jewellery designer.

-

The Rose Tao Water Dragons hand ornament.

-

The Celestial Lotus necklace.

-

The Monet Water Lilies necklace.

-

Myth of the Orchid earrings.

-

The Duchess Hibiscus ring collection.

-

The Butterfly Lovers ring.

-

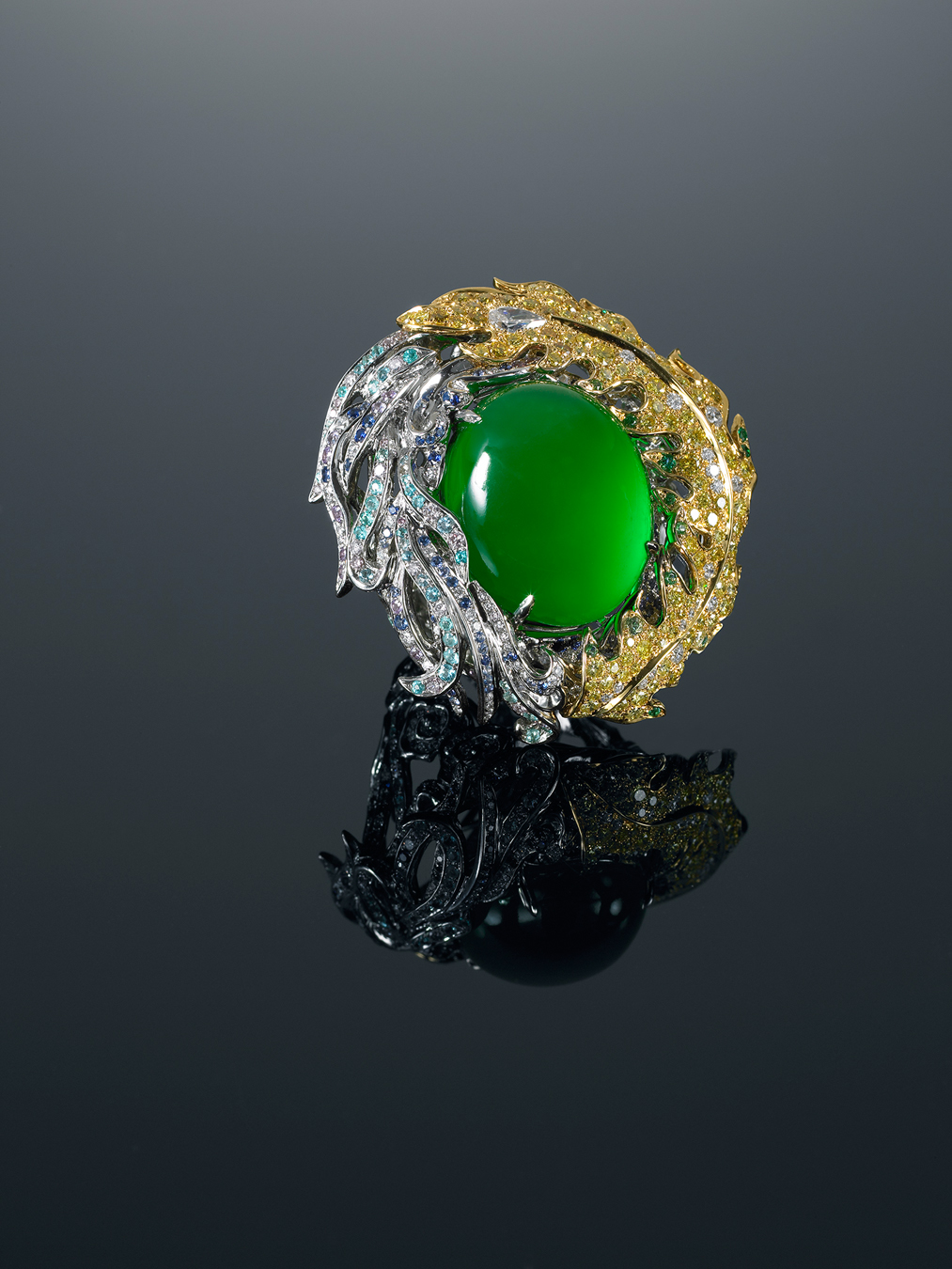

The Jade Phoenix ring.

Anna Hu

Fine jewellery finesse.

Those meeting Anna Hu for the first time would be forgiven for feeling somewhat confounded. Quiet and unassuming, the fine jeweller in person is rather at odds with her seriously knockout gems and impressive CV: A-list celebrities such as Madonna, Scarlett Johansson, Natalie Portman, and Emily Blunt have worn her beautiful, high-octane creations on the red carpet; in 2012, just five years after launching her brand, Hu became the first Asian jeweller to have a solo exhibition at the Louvre’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and the following year she broke three world auction records at Christie’s—one of which, the $4.2-million Swiss franc ($4.8-million Canadian) sale of her exquisite Côte d’Azur brooch, set the record for the highest price for work by a contemporary designer. Hu took the distinction from the Paris-based JAR (Joel Arthur Rosenthal), and still holds the record today.

Little of this is apparent on the summer afternoon that I meet the 38-year-old in a hotel restaurant in London’s Mayfair. Instead, Hu is full of apologies: for arriving late, and for not wearing any of her jewellery. Her politeness and modesty is disarming. “What’s so great about Anna is that she’s this kind of pretty, little, dainty person,” says Elizabeth Saltzman, Vanity Fair’s contributing editor and a stylist who counts Gwyneth Paltrow, Gemma Arterton, and Olga Kurylenko among her clients. “But what you don’t expect is this grand-slam of a whopper [of jewellery] to slap you in the face. It’s like, ‘What was that?’ ”

Hu’s gems truly do “stay in your brain”, to use Saltzman’s words—so ingenious are they in their masterful craftsmanship and use of rare, jaw-dropping stones. Born in Taiwan to a diamond-dealer father and jade-and-pearl-expert mother, Hu may have had jewellery in her “DNA and blood”, as she says herself, but it wasn’t, in fact, her first calling. A gifted cellist, Hu at 13 was selected by the Taiwanese government to study abroad in the United States, by which she spent four years at Boston’s Walnut Hill School for the Arts. A top highlight included playing alongside her icon, Yo-Yo Ma, and it was during this time that Hu also complemented her music theory courses with those in sculpture, ceramics, and art—underscoring a passion for scholarship that would continue throughout her career.

At age 20, however, Hu was diagnosed with shoulder tendinitis, which cut her music career short and led her to turn to jewellery design. Despite mourning the loss of a childhood dream, Hu felt the transition was very natural. “All I remember growing up was either practising music or helping my daddy look at diamonds,” she recalls. “I would practise for an hour and a half, then take a 30-minute break—going from one room to the next—where my daddy would say, ‘Help me sort these stones for colour and size’ … So I had an early start. I received all my training even before I decided what I wanted to do.”

After receiving her gemologist degree at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) and completing studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology, Parsons School of Design, and Columbia University, Hu went on to apprentice at the top haute jewellery houses in New York, including Van Cleef & Arpels and Harry Winston, as well as at Christie’s. During this time, she perfected her personal, unique approach to jewellery design, one that “combines the music theory I learnt as a child, and applied to jewellery composition,” she says. Melody, she explains further, is akin to a jewel’s curve and line, while rhythm—structure and style—can be manifested as, say, either an angular or bulky form. Finally, Hu says, harmony dictates colour—and so a key to her work is the unusual range of hues that she is able to source, keeping her clients coming back.

Melody, Anna Hu explains, is akin to a jewel’s curve and line, while rhythm—structure and style—can be manifested as, say, either an angular or bulky form.

If music is signature to Hu’s jewellery-making, so too is an infusion of east and west. Hu has ateliers in Paris and the U.S. and while this brings a western sensibility to her Chinese background, “it’s much more complicated than that,” she says. “A lot of jewellery, especially from Asia or China, is too surface-level; things are not as simple as ‘here is a dragon, hence it’s Chinese.’ I’ve yet to see an organic-like chemistry from another jeweller, and my aim is to add eastern and western elements—but in a sophisticated way.” Cue her figurative Dragon Flower ring, where the mystical creature weaves around a flower fashioned from two gobstopper-like Burmese rubies, set amid an explosion of white and yellow diamonds and pink, blue, green, and purple sapphires. There is nothing obvious about the dragon—or the flower for that matter—yet the nod to the age-old Chinese symbol is unmistakable.

It’s the same with her Fire Phoenix earrings, which Paltrow wore with a pale-pink Ralph & Russo dress to this year’s Oscars. Reminiscent of early 19th-century pendeloque earrings, the set’s double pear-shaped rubellites weigh a total of 124 carats, and are framed by a flaming torrent of white and vivid-yellow diamonds; blue, pink, and purple sapphires; and Paraiba tourmalines. Legend has it that the immortal phoenix sets itself on fire at the end of its life cycle, and Hu mixes this tale with her own—of a raging blaze she witnessed on a trip to Bhutan—producing a one-of-a-kind gem that does not actually feature the mystical bird, yet equally does. “Chinese culture should be spiritual rather than literal,” says Hu.

Other designs are clearly more western, such as her Monet Water Lilies necklace, hand ornament, and earring set. The pieces took more than two years to create and are set with over 2,000 rare stones that Hu and her father had purchased together on a single buying trip in New York. The design continues Hu’s translation of eastern floral motifs, such as the peonies and orchids she’d referenced in the past, but this time inspired by a summer spent in Giverny, France—and, specifically, at the Claude Monet gardens. Expertly executed and also technically superior, the works feature deep-pink sapphire lilies set amid a rush of colour, courtesy of tsavorites, tourmalines, morganites, alexandrites, natural pastel-coloured sapphires, white, pink, and silver-grey diamonds, and a 45.22-carat cabochon tanzanite—and pay homage to the Impressionist works that appear time and again in Hu’s oeuvre. “Anna has a belief in all different types of art,” says Saltzman. “She can make a diamond cocktail ring like anyone else, but not everyone can make a Water Lilies necklace.”

Demand is growing for Anna Hu Haute Joaillerie, the eponymous brand she launched at age 30—with strong interest in particular from the Middle East and, of course, Asia. Boutiques opened in Shanghai and Taipei in the past two years, where there are waiting lists for her signature Duchess Hibiscus rings. Still, it’s hard not to feel that the height of Hu’s powers is yet to come. In 2012, following her Musée des Arts Décoratifs show, her first book, Symphony of Jewels: Anna Hu Opus 1, was published by Thames & Hudson, featuring introductions by the gem writer Janet Zapata and Vogue jewellery editor Carol Woolton. The book detailed Hu’s first 100 haute jewellery creations. “Beethoven was unable to complete 10 symphonies, but his goal was to,” Hu tells me. “Every five years I want to put together an opus … I feel like I am changing all the time, and need 10 books to document all the changes.”

Indeed, work on the jewellery that will be, eventually, featured in Opus 2 has begun, spearheaded by a breakthrough butterfly design that, in classic Hu fashion, is a tribute to the five elements in Chinese philosophy (wood, fire, earth, water, metal) and infused with western theories of colour (Van Gogh, Monet, Rembrandt, and Rothko are all referenced). Like with her previous leitmotifs, whether floral, fauna, or mystical beasts, Hu has been painstakingly studying specimen after specimen of the time-honoured insect (“I’m trying to get into the bone to show the skin”), with the goal to ultimately create pieces that “will not look like the butterfly,” she explains. “It’s simple and effortless and probably only a thousand people will understand.” The process has challenged her technically, too. She has been hard at work experimenting in her Paris studio—one which, incidentally, is also used by JAR—on a “paper-thin” metalwork for the setting. “It’s a very special alloy between rose gold and a shiny yellow, almost a lemon-yellow gold,” she describes. “My head jeweller, who is from Van Cleef, says I’m crazy. But we’re having a lot of fun.”