-

Blake Mycoskie. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

-

Inside the Mycoskie home in Topanga Canyon, Los Angeles. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

-

Inside the Mycoskie home. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

-

Inside the Mycoskie home. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

-

TOMS Eclipse Cultural Woven Men’s Classic shoe.

-

TOMS Jasper eyeglasses.

-

To date, over 250,000 people have been helped through TOMS’ one-for-one optometry program.

-

Blake Mycoskie. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

-

TOMS Taupe Leather Men’s Brogue.

-

The TOMS flagship store in Venice, California.

-

A shoe tent inside the TOMS flagship store in Venice, California.

-

TOMS Leather Caravan Backpack in Caravan Cognac.

-

TOMS Traveler Duffel in Indigo Ikat.

-

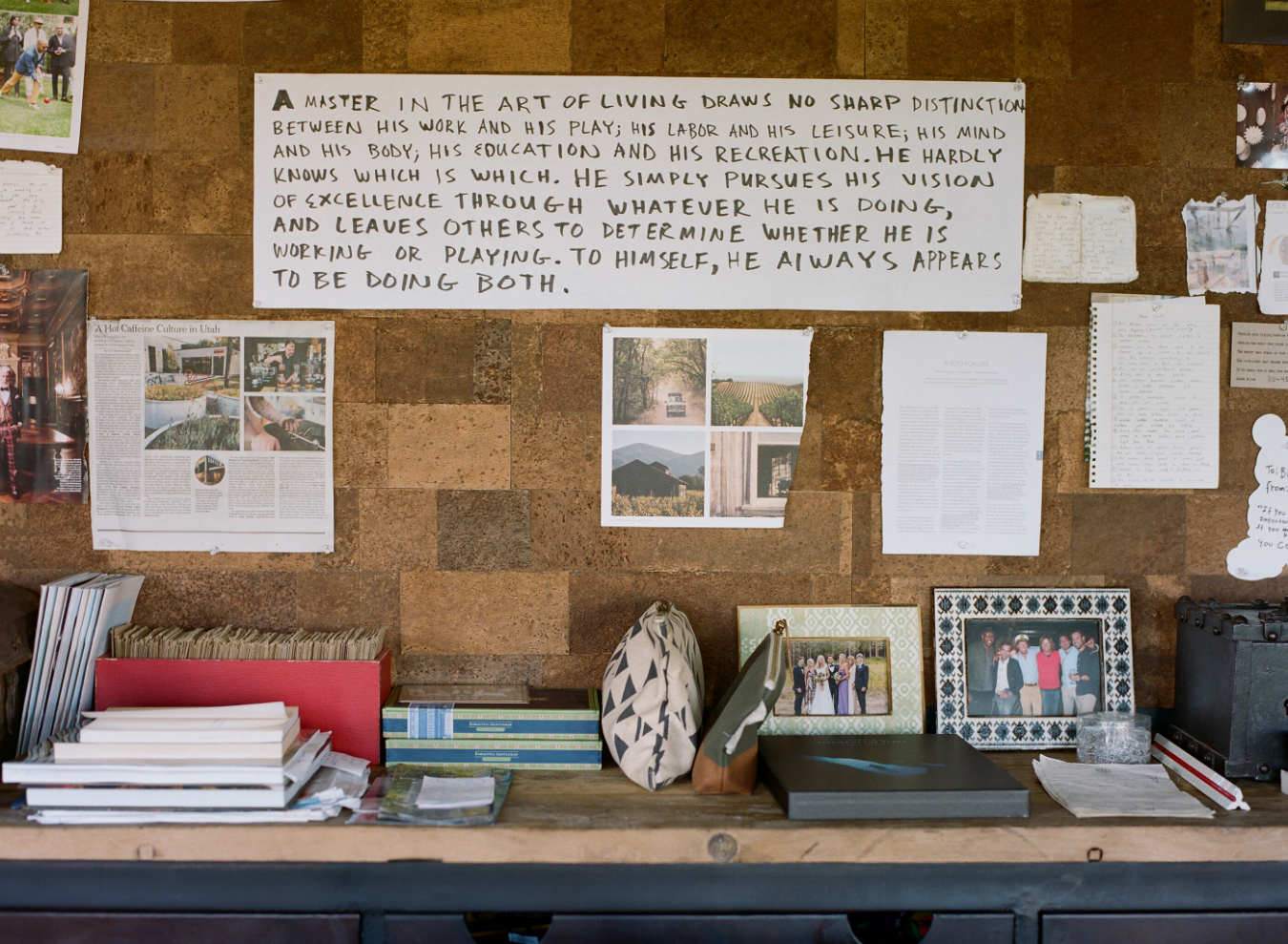

A quote by the British philosopher L. P. Jacks inside Blake Mycoskie’s home. Photo by Ye Rin Mok.

Blake Mycoskie

The TOMS manifesto.

A Post-it note affixed to the glass door of Blake Mycoskie’s woodsy farmhouse in Los Angeles’s Topanga Canyon contains a command softened by a smiley face: “Shoes off :-)”.

It’s more than a little ironic, but only if you know Mycoskie’s by-now-legendary story: In February 2006, while on vacation in Argentina, he struck up a conversation with a woman in a café on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. She and her fellow volunteers were on their way to a nearby village to hand out shoes to children whose parents couldn’t afford to buy them. Mycoskie tagged along.

By the time the then-29-year-old Texas-born entrepreneur returned to his apartment in Venice, California, he’d founded TOMS. (He had been playing with the names “Shoes for a Better Tomorrow” and “Tomorrow’s Shoes”.) The for-profit company, which gives a pair of shoes to a needy person in a developing country for every pair they sell, has donated more than 35 million pairs of shoes worldwide in nine years—all types of shoes, depending on the climate and region—pioneering a widely emulated business model known as “one-for-one”.

Shoes, however, aren’t really the point.

Mycoskie makes this clear shortly after opening the door on a brisk December morning. Still in his pyjamas, he brings a finger to his lips in the universal gesture of “quiet, please”.

That’s because his 10-day-old son, Summit Locke Mycoskie, is asleep on the main floor of the home he shares with his wife, Heather Lang Mycoskie, whom he met while surfing in Montauk, New York, and married in Sundance, Utah, in 2012. Even though Mycoskie is at the start of a two-month paternity leave that includes what some might consider a radical commitment to unplugging (“I took e-mail off my phone and my computer!”), he’s anxious to talk about TOMS’ newest initiatives. Chief among them: its year-old coffee business, the company’s first foray outside the world of fashion and lifestyle accessories.

“It goes back to me taking a sabbatical,” Mycoskie says as he tears open a chocolate breakfast bar. “I was living in Austin and travelling. I came back to the company in May 2013 after about 18 months off and part of the reason I came back is that I got really good clarity about what I wanted TOMS to become long-term and how I wanted to be engaged in it.

“I loved the giving part, but the shoe business part wasn’t feeling as creative as it once was,” he says. “I realized that in order to take TOMS from a shoe company to the original one-for-one company, we needed to do something no one would expect.”

Having spent time on shoe-giving missions in countries like Ethiopia, Guatemala, and Rwanda, Mycoskie, like other social-responsibility pioneers who came before him, recognized that working with coffee bean farmers using a fair-trade model could help them earn better prices for their beans. The one-for-one give was obvious: “They use so much water to create coffee, I thought the giving back of water would be nice,” he says.

Mycoskie joined forces with the Denver-based non-profit Water For People to ensure that when someone buys a bag of TOMS Roasting Co. coffee, the company provides a week’s worth of safe water to a person in need.

That, however, wasn’t the only big TOMS news of 2014. Last August, Mycoskie sold 50 per cent of the company to Bain Capital for a reported $325-million, concluding a six-month search for a private-equity partner experienced in growing global consumer product businesses.

“I wake up every morning and it’s not just on me,” he says. “Now I’m back to doing things I love: focusing on our giving partners, launching new ideas and products, and all that.” As of February, “all that” includes TOMS’ newest product line, a casual handbag collection comprising totes, clutches, and backpacks. The one-for-one promise here: for every bag purchased, TOMS will donate a kit to an expecting woman in a developing country who plans to give birth in her home, to prevent infections that can lead to maternal mortality. “The kit has a drapery that you put on the ground so the mother can give birth in a sterile environment,” Mycoskie says. “It has the gloves; it has the tools to cut the umbilical cord; it has soaps—everything you need.”

There is an element of serendipity in the birth-kit give as there is with most of the projects in Mycoskie’s life: after he started working on the handbag line, Heather became pregnant. It’s enough to make you wonder if a lucky star was hovering over Arlington, Texas, on August 26, 1976, when Mike and Pam Mycoskie welcomed their first child, Blake, into the world. Luck, however, is the least of it.

As Mycoskie recounts in Start Something That Matters, his 2011 guide to aspiring entrepreneurs, his mother was a stay-at-home mom who successfully self-published a cookbook in 1994—imparting an early lesson about the value of risk taking. At age 19, while he was studying philosophy at Southern Methodist University, Mycoskie started a campus laundry service that became so successful he left school in order to work on it full-time.

“I’ve always been someone who follows my curiosity, and part of the success is being able to approach new industries with a virgin mindset.”

From Texas, Mycoskie moved to Nashville, Tenn., where he founded an outdoor advertising company that he eventually sold to Clear Channel. Up to this point, he was not well travelled by any means, but that changed dramatically in 2002 when Mycoskie and his younger sister, Paige, circled the globe in 31 days as contestants on season two of the CBS reality series The Amazing Race. Although they lost out on the million-dollar prize by mere minutes, the experience lured Mycoskie to Los Angeles, where he settled in the seaside community of Venice.

Ever the entrepreneur, he wasted no time applying his trademark can-do attitude to another venture, a reality TV channel. It flopped, but Mycoskie was undeterred. “I’ve always been someone who follows my curiosity, and part of the success is being able to approach new industries with a virgin mindset,” he says. “They all led to more non-traditional thinking, and they all culminated in TOMS.”

In early 2006, Mycoskie chose Argentina for a month-long vacation because he wanted to learn how to play polo. At the time, he was running an online driver’s education company that was making money but, by his admission, “wasn’t super fulfilling.” Not that he was looking to business for anything but profits. “It was always in the back of my mind that I’d be a businessperson-entrepreneur doing creative things with a purpose greater than making money, but I always thought that would be in my 60s and 70s,” Mycoskie says. “I never thought you could do both at the same time.”

After accompanying the volunteers on their shoe drop in the Argentinian countryside, Mycoskie relayed the experience to his polo instructor, Alejo Nitti, who challenged him to come up with a model that provided a sustainable source of shoes to needy kids—one that didn’t depend on donations from family and friends. Mycoskie had noticed the popularity of a local shoe style, the alpargata, a simple canvas slip-on favoured by Argentinean farmers. “You guys have all these cool little shoes you wear down here and we don’t have them in the States,” Mycoskie recalls telling Nitti. “What if we sell one in Venice and we give one to you? That’d be supercool!”

Nitti was enthusiastic about the idea, giving Mycoskie the encouragement he needed to pursue it. Mycoskie spent the remainder of the trip meeting shoe suppliers in Buenos Aires to make 250 samples, which he stuffed into three duffel bags on the flight home.

The fledgling company sold its first pair of shoes in June 2006—“a [size] nine-and-a-half camo patch to a guy named Ben Katz online,” Mycoskie recalls. (You can now find the shoes everywhere from Hudson’s Bay to Whole Foods.) Later that month, the Los Angeles Times featured TOMS in a weekend article—“and, boom, we sold 2,200 pairs that day on the website,” he says. “We only had 160 pairs in the apartment, so it was a little issue.”

A frantic scramble for interns ensued. Mycoskie went back to Argentina and stocked up for the tidal wave of orders that was coming. “The next big milestone was Vogue,” he says, referring to a feature in the American fashion bible’s October 2006 issue. “Since then, it’s never slowed down.”

In 2011, TOMS expanded into the eyewear category with another one-for-one offer: for every pair of sunglasses or optical frames the company sold, they’d help restore the sight of a person in need by donating prescription glasses, medical treatment, or sight-saving surgery. (To date, more than 250,000 people have been helped through this program.)

But Mycoskie wasn’t content to remain a manufacturer of consumer products. In the midst of his sabbatical, in December 2012, TOMS opened its first café-cum-retail-store on a chic stretch of Abbot Kinney Boulevard in Venice. On a recent afternoon, the space—strewn with ethnic rugs and decorated with postcards, textiles, and mementos—hummed with a chilled-out energy, as shoe buyers mingled with coffee drinkers, laptop-wielding surfers, and pooches sunning themselves on the Astroturf in back.

Over the past year, TOMS has opened similarly appointed cafés in Amsterdam, Chicago, Austin, and Portland, with New York and potentially London on deck for this year. Reinventing the café business is Mycoskie’s next big hurdle. The idea is “to create a community space for people to hang out, bring their dog, have a meeting,” he says, as he looks around the cozy family room in his Topanga Canyon farmhouse, which, despite its lived-in vibe, has been home to the Mycoskies for only 45 days. “We want to create an environment, much like this room, that is really comfortable for people, and has different artifacts from our travels.”

A veteran globetrotter, Mycoskie recently returned from a week-long trip to Haiti, where TOMS opened a shoe factory in early 2014 to help spur the growth of a sustainable shoe industry. The factory is a rejoinder to critics who’ve assailed the one-for-one strategy for failing to alleviate the source of poverty in countries where the company donates shoes.

Mycoskie often consults the teachings of Eastern philosophers, such as the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh, whose book The Art of Power is one of Mycoskie’s favourites. “It’s about how the West talks about power in one way and the East talks about mindfulness and power in a totally different way,” he says. “I’ve read it over and over again.”

Not only is Mycoskie a voracious reader of tomes by business and thought leaders, he’s networked with the best of them. In 2013, he and Heather vacationed at Richard Branson’s private game reserve in Ulusaba, South Africa, where he met Nobel Peace Prize winner and Bangladeshi microfinance evangelist Muhammad Yunus.

“He’s basically banked the poorest people in the world, shown how they can repay their loans, given out microcredit,” Mycoskie says. “That’s one of the things we’re doing with our factory in Haiti—focusing on creating jobs and not just giving aid.”

It’s easy to see a future in which the “TOMS movement”, as Mycoskie calls it, unites all of his myriad passions, from fair-trade coffee to microcredit. But for now, Mycoskie is content to nest in the canyons of L.A. His office has a view of the tree canopy, which lends the room a clubhouse feeling. Is he working hard or hardly working? On the wall, a quote by the British philosopher L. P. Jacks says it all:

“A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play; his labour and his leisure; his mind and his body; his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always appears to be doing both.”