-

UBC Faculty of Law. Photo by Selwyn Pullan.

-

Interior lighting design of the Malmgren house. Photo by Selwyn Pullan.

-

Photo by Selwyn Pullan.

-

The Rudden house. Photo by Selwyn Pullan.

-

Interior shot of Hollingsworth’s own house in the Capilano Highlands development. Photo by Fred Hollingsworth.

-

Photo by Fred Hollingsworth.

-

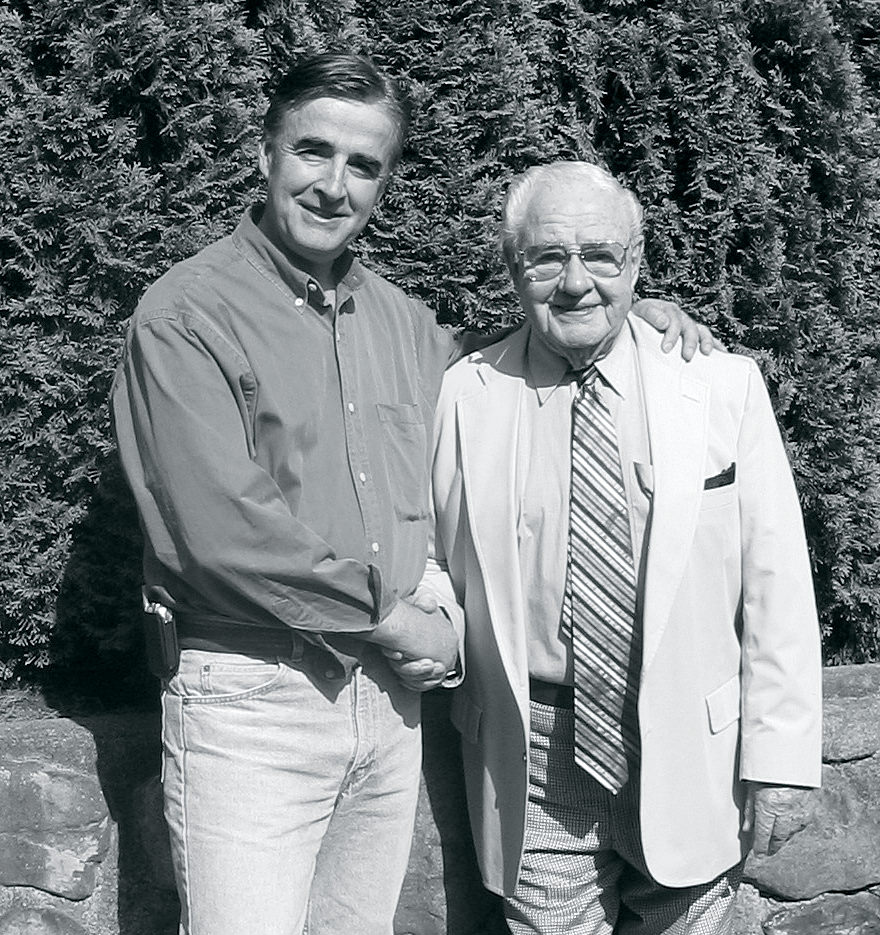

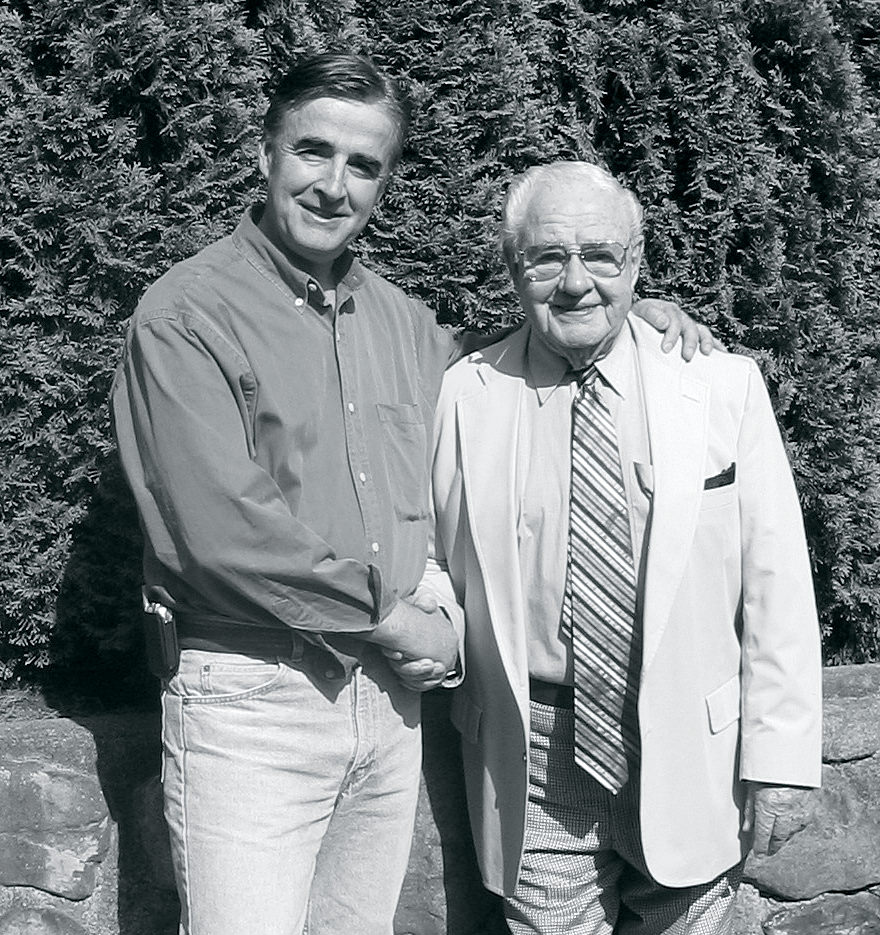

Russell and Fred Hollingsworth.

-

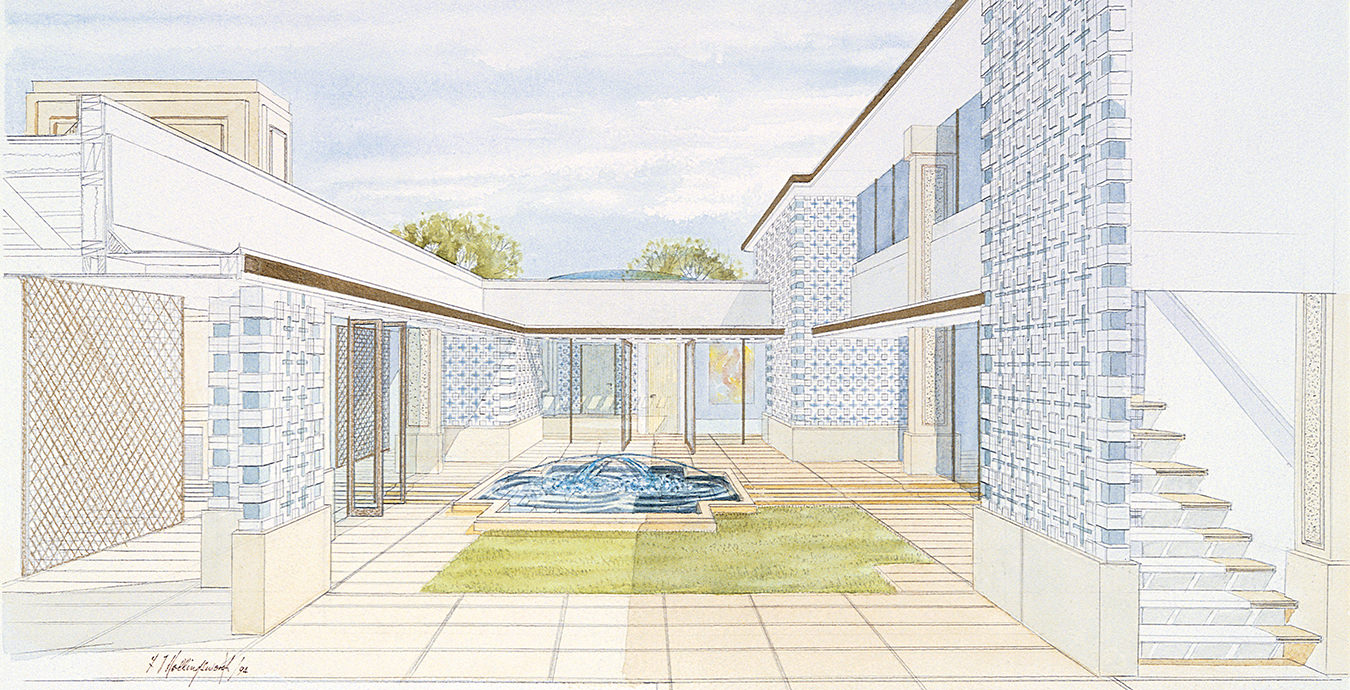

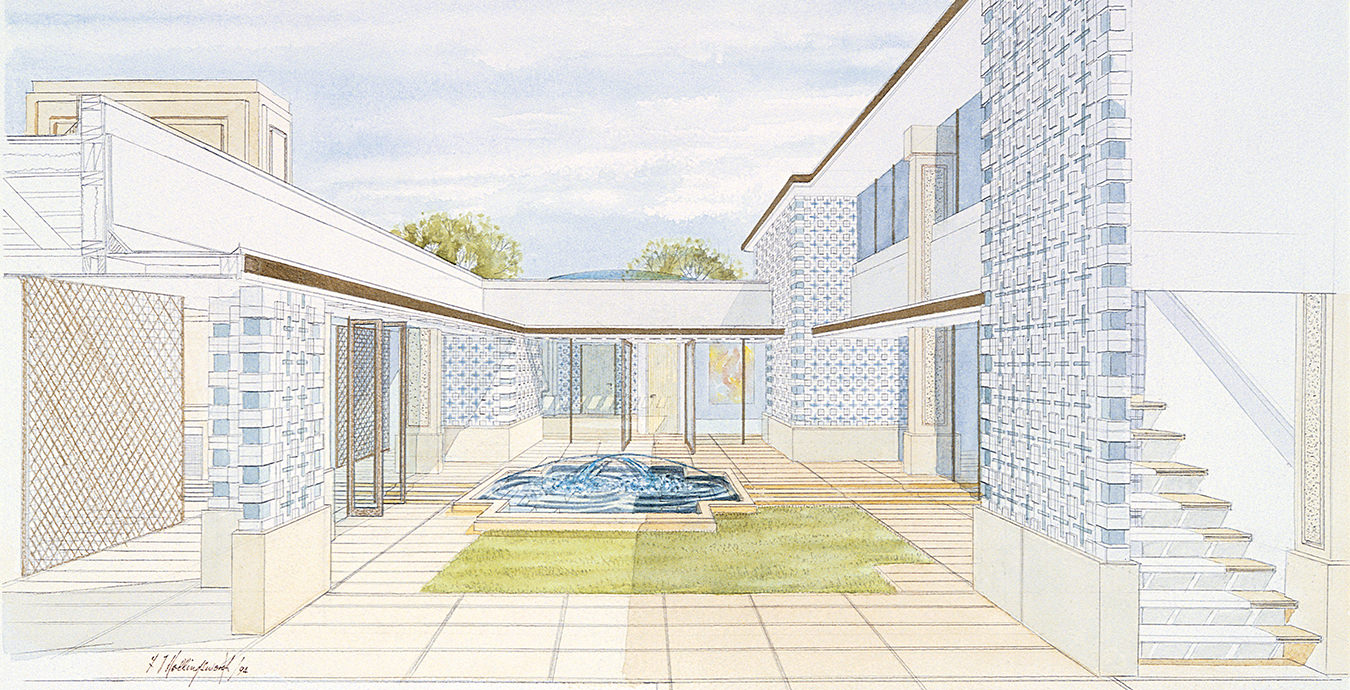

Drawing of the Kassam house.

-

Exterior of Kassam. Photo by Barry Downs.

-

Indoor pool shot of the Bosa house. Photo by Barry Downs.

-

Exterior shot of the Bosa house. Photo by Barry Downs.

Architect Fred Thornton Hollingsworth

An archetype of style.

When does good design become a distinctive style? According to Fred Thornton Hollingsworth, good design never becomes a style because good design is all about planning a solution to an individual problem. Fred Hollingsworth has practiced architecture for more than 60 years, designing solutions for the way people live in homes and occupy public buildings.

Hollingsworth is one of the very small group of architects who are credited with what has come to be known as West Coast Modernism—perhaps the closest we have come in Canada to developing a regional indigenous style of architecture. Hollingsworth designed his first home in 1946 in North Vancouver—the home in which he still resides today with his wife, Phyllis. It is the design of that home that launched his long and prolific career in architecture. That career has resulted in a significant body of work, much of it award-winning private residences, mainly on Canada’s west coast.

Hollingsworth is perhaps best known as the designer of the building that houses the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Law, a work he completed in 1971. The all-concrete building, with its artistic use of exposed aggregate, blends the interior space into an exterior central courtyard garden. Working seamlessly with nature, both outside a building and inside is a principle of organic architecture and one closely adhered to by Hollingsworth throughout his long career.

The Rudden house. Photo by Selwyn Pullan.

There is some irony in the fact that both Hollingsworth and his son, Russell, became architects by following what would be considered today an unconventional path; they practiced the craft and learned their skills through drawing, conceptualizing, modelling, detailing and actually constructing buildings. They both practiced the craft of architectural design without being formally educated in architecture. In fact, both were designing homes, drafting plans and overseeing the construction of buildings before they were registered architects.

A craftsman is someone who creates and performs, confronting a challenge by applying both the boundless creativity of an artist and the functional detail of a builder. Russell Hollingsworth, who is the second-generation craftsman of the family, says an architect is part scientist, a big part businessperson and part artist. His father Fred started out as a craftsman and remains one today as an architect whose work people point to as representing not only something that was ahead of its time when it was designed but also architecture that is timeless.

Hollingsworth immigrated to Vancouver from England in 1929 with his family at the age of 12. He has been drawing as a hobby for as long as he can remember, winning a prize for a sketch of a sailboat at the age of six. Hollingsworth began earning a living with his drawing skills at the outbreak of the Second World War at Boeing Aircraft in Vancouver where float planes were built for the war. He was a draftsman, drawing perspective sketches of complicated plans for aircraft assembly.

Interior shot of Hollingsworth’s own house in the Capilano Highlands development. Photo by Fred Hollingsworth.

After the war, Hollingsworth started designing the home he planned to build. When he needed to get his drawings approved for the proposed home in the emerging Capilano Highlands district of North Vancouver, he walked into the office of what was one of Vancouver’s biggest architectural firms of the day, Thompson, Berwick and Pratt. The firm had been appointed to review builders’ plans to ensure they met the developer’s vision for the new community.

“I’ve always said a home is an escape from the world; a place to which you escape to reconnect with nature.”

Hollingsworth showed his drawings to Ned Pratt, a principal of the firm. Pratt commented on the quality of Hollingsworth’s work and asked which architect had prepared the drawings. When Hollingsworth informed Pratt he had drawn the plans himself, Pratt immediately offered Hollingsworth a job in his busy architectural office as a draftsman with the promise of becoming an architect. Hollingsworth started the next day.

In his spare time, Hollingsworth began designing homes. It wasn’t until 1959 that he qualified to be registered as an architect after writing exams. That’s when he set up his own practice in his home. He attracted many clients who his son describes as members of the emerging middle class who had been through some tough war years and they wanted a different way of life. “They didn’t want to live in these funny little imported stylizations of the east coast or California. They wanted something that worked for them,” the younger Hollingsworth explains during an interview with both father and son together at a dining table the senior Hollingsworth designed for his own home, that first home, in which we met.

“There was a market—the clients—and there was this group of guys, like Dad, who just wanted to do great stuff that responded to the nature that they loved and to the things that they held dear.” Most of the clients weren’t rich people, but natural materials were plentiful and many homeowners were involved hands-on in building the homes his father designed.

Fred Hollingsworth enjoyed designing custom homes more than any other building.

“I’ve always said a home is an escape from the world; a place to which you escape to reconnect with nature. When you are going home, you are going home,” he declared.

“My clients were all individuals. Many people had different interests. I tried to get into their lives. I tried to find out how they used their space.” Many of Hollingsworth’s clients became close friends who he still keeps in touch with. The homes he built for them are icons of a distinctive style of architecture that speaks so clearly to ideals many in the design and building fields are striving to achieve today. Hollingsworth and his small group of compatriots were designing and building homes 50 years ago that embraced what we call “green building” and sustainable-development principles today.

Most of Hollingsworth’s homes are single-storey bungalow-style homes, many with flat or very shallow-pitched roofs. He rarely designed in a two-storey form unless the client demanded it or it was the only design solution for the site. Hollingsworth maintains that architectural design is all about individual solutions for individual problems. “I think you belong to the ground. You need to be able to walk in and out of the home. You need doors that you can open and you need to be able to belong to nature that is your site.”

The magic of Hollingsworth’s creations comes from his extra sensitive powers of observation, discerning the most intricate of details.

While Hollingsworth is loath to define his significant body of work as representing a distinctive style, it is inspired by the principles of organic design as best articulated by Frank Lloyd Wright. Much of Hollingsworth’s work fuses the influences of Wright’s organic architecture with those that flow from principles of traditional Japanese design. “I always understood the West Coast style simply grew out of solutions to suit certain problems wherever you encountered them,” Hollingsworth explains, in trying to emphasize his very practical approach.

His designs bring interior and exterior together with large rear windows in buildings that are usually single-loaded open spaces oriented to the expansive rear views. He tried not to isolate people from nature by enclosing them in rooms, so the open plans usually have a hub with functional spaces radiating out from that hub. Both Hollingsworths, father and son, are known for their extensive use of indigenous materials. In the early days when West Coast cedar and other wood products were abundant and inexpensive, Hollingsworth used them extensively. Concrete, finished with an exposed aggregate finish, is also a favourite natural material.

Russell and Fred Hollingsworth.

He often employed unifying elements in design, such as a continuous valance board wrapping the walls of an entire space at door-height. “It brings the scale down, making people feel more comfortable in the space. In the old days, when there was little money, we could hide very simply light fixtures behind it for indirect light,” Hollingsworth explains. With the same finger that has guided the architect’s pencil that literally created thousands of drawings and the hand that clutched the artist’s brush that painted many watercolours over the years, the 89-year-old Hollingsworth was quickly winding the propeller on a delicate rubber-band-powered model airplane. He had carefully removed the plane from a drawer full of balsa-wood models of various designs that he has built over the years.

Since he was a young boy, Hollingsworth has been fascinated with the principles of aerodynamic design. He gave up piloting his own Cessna 180 a few years ago but continues his lifetime passion of building model planes and flying them both recreationally and competitively. He holds contemporary records for flight times and distances with his mini model aircraft.

We were about to fly one of them in his basement studio, in that timeless house he built 60 years ago. Hollingsworth was ready to launch into flight what looked like a giant, gangly insect. With a careful nudging throw, the propeller began to turn and the model plane began to gently fly through the architect’s studio, almost floating as it banked to begin a slow circuit of the room. The airfoil was deliberately designed to cause the craft to pitch and bank as Hollingsworth had planned.

It was at that moment that I realized the real meaning inherent in all of Hollingsworth’s work over six decades. His body of architectural design work represents the observations and interpretations of a curious man who has spent a lifetime exploring the most basic principles of design—those principles inherent in everything natural around us in our world. The magic of Hollingsworth’s creations comes from his extra-sensitive powers of observation, discerning the most intricate of details. That magic unfolds with his ability to see things in an integrated way and to conceptualize the world’s picture before him, exploring that form by translating the picture in his mind into a picture on paper. “Dad has an incredible ability for three-dimensional perception,” his son said.

“He sees things that way in his mind. When I worked with Dad in his office, he would often say to me, ‘Stop drawing because I can tell you don’t have it in your mind yet.’ He sees it all in his mind before he draws anything on paper.”

It is that artist’s ability to combine pencil lines and splashes of colour that has allowed Hollingsworth to bring alive nature’s details—transforming the principles inherent in them into tangible constructed forms. Perhaps it is Hollingsworth’s practical sensibility more than anything else, a common sense, down-to-earth approach, that has enabled him to take what others have only been able to intellectualize and actually apply it to how people live and interact with the natural environment.

Exterior of Kassam. Photo by Barry Downs.

He has made our built environment, especially the homes he designed, that much more relevant, pleasing and functional. Frank Lloyd Wright shaped Hollingsworth’s thinking right from his earliest days as an architect. He travelled to both of Wright’s most renowned projects, Taliesin East and Taliesin West, to meet with his inspirational idol. He embraced Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophy of organic architecture.

Wright described organic architecture not as a style or an imitation, but rather a design philosophy that sees building forms as a reinterpretation of nature’s principles as filtered through the intelligent mind of a human being. Wright’s purpose was to create built forms that are more natural than nature itself. It is ironic that not one, but two generations of creative minds in the Hollingsworth family were able to honour Wright’s purpose with such authenticity. The real marvel is that both Fred Hollingsworth and his son Russell have made such an influential contribution to the application of organic architectural principles, both without formal education in architecture and both displaying a strong reverence for nature.

The Hollingsworth name is a brand name for West Coast Modernism, whether it is a style of architecture or simply a body of work that represents different ways to respond to nature, to the immediate site context and to the lives of those who will occupy a building. Their combined work spans six decades and two generations. At the conclusion of our interview Russell reminded his father that one of his clients was retaining the senior Hollingsworth to draw a rendering of a home Russell is designing for them.

Indoor pool shot of the Bosa house. Photo by Barry Downs.

Russell is following in his father’s tradition—designing practical solutions for individual problems, working with nature as seamlessly as possible. At the same time, he doesn’t mimic his father’s work, nor is he necessarily limiting himself to simply designing homes. For nearly two decades, the younger Hollingsworth has been both designing homes and building them as a contractor who also retains many in-house craftsmen to transform his designs into real, built form. Recently, he ventured into the development business, with his Hollingsworth Homes, a 26-acre site in West Vancouver targeting what he calls “production housing” to the empty-nester market.

The Hollingsworth name that is synonymous with the excellence and sensitive innovation of organic architecture won’t just continue on in the large body of work produced by both father and son, but it will perpetuate with a growing body of new work. Organic architecture, both Hollingsworths agree, can be called modern architecture because it is about doing things in a new way, in a functional way that responds to nature, but without discarding the patterns of nature.

Fred Hollingsworth, the practical man, tried to describe the purpose of his life’s work. “It’s been about revealing to people the wonders that are in the simplicity yet diversity of nature. There is no raindrop or snowflake that is alike. Nature is so varied. This delights the human eye.” Russell Hollingsworth best explained the character of the design work of he and his father. “It is intuitive, un-intellectualized and a natural response to the environment. In short, it’s really common sense.” Both father and son represent a very unique melding of skills, passions, abilities and sensibilities as architects. This is the melding that allows the magic to flow from the hands of true artists who are also artisans and craftsmen. Their contributions have made living better for those who occupy the homes and buildings they have designed.

Exterior shot of the Bosa house. Photo by Barry Downs.

All photos and drawings courtesy of Hollingsworth Architecture and Living Spaces: The Architecture of Fred Thornton Hollingsworth (Blueimprint).