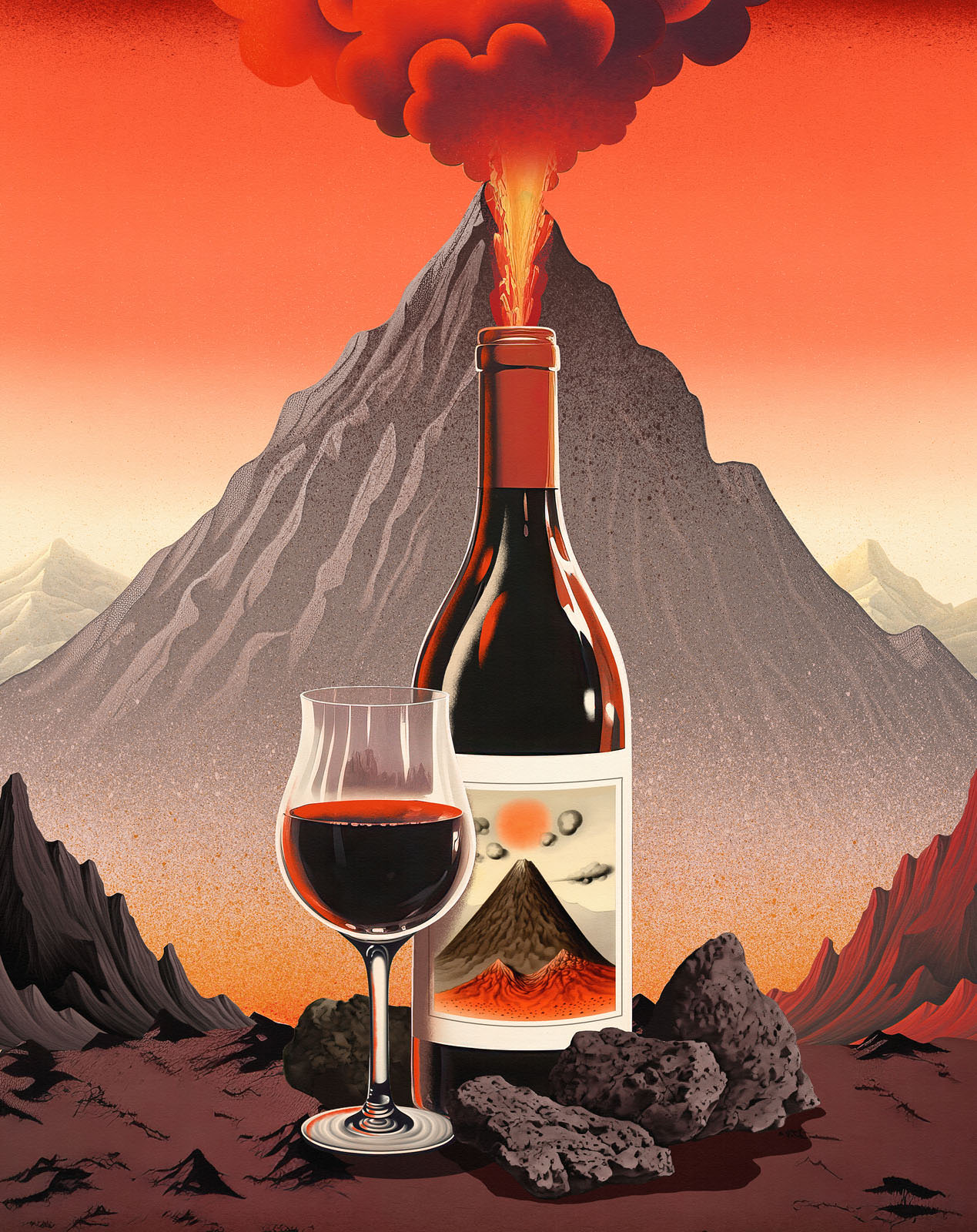

Get All Fired Up With Volcanic Wines

Volcanic wine is a complicated category.

Volcanic wines erupted onto the world’s wine landscape in the early aughts and quickly developed cult status. Produced from grapevines growing in the rocks and ash deposited by volcanic activity, these wines are made in countries as diverse as Chile, Italy, the United States, and New Zealand—wherever there are regions that have seen volcanic eruptions, even if they were thousands or millions of years ago.

Although grapes have long been grown in these regions, the notion that the wines they produce are boldly distinctive—that “volcanic wine” is a category in its own right—is quite new. Not only have volcanic wines been quickly embraced by many wine-lovers—those produced on the slopes of Sicily’s Mount Etna are especially popular—but the name gives producers in these regions a way of differentiating their wines in a crowded market.

What makes volcanic wines distinctive and deserving of such attention? Are they compelling due less to the wines themselves than because volcanoes occupy such a special place in so many cultures? Their sheer power, and the fire, steam, rocks, and lava they vomit—seemingly from the very centre of the Earth—have inspired awe and terror for thousands of years. Some cultures regard eruptions as signs of divine anger. Others simply fear the devastation they can cause.

Or is it because volcanic wines have qualities that are absent from wines produced in other conditions? Many wine critics believe volcanic wines have discernible qualities, among them that they are powerful and have high acidity and intense flavours. John Szabo, a Toronto-based Master Sommelier and author of Volcanic Wines: Salt, Grit, and Power, sees a general profile in volcanic wines. “All things being equal,” he says, “volcanic wines tend to be more savoury, spicy, and salty, with riper, highly concentrated fruit and, yes, occasionally smoky-stony flavours.”

The question is whether all wines from volcanic soils share these characteristics and whether they are also found in nonvolcanic wines. For volcanic wines to be a separate category, they should generally share characteristics not found in other wines. The argument that volcanic wines are distinctive rests to some extent on the notion that wines express flavours and characters of minerals in the soil and rocks they grow in. Many of the words used to describe wine relate to rocks: slaty, wet stone, mineral, chalky, gritty, and so on. Often the influence of soil and rock is assumed to be the most important part of terroir, the total environment in which vines grow—which is why so many back labels on wine bottles describe the geology of the vineyard. The term minerality captures the idea that wines can express the minerals in the soils and rocks of a vineyard.

However, scientists have debunked the notion that minerals in soil and rocks are taken up by vines in any way that we can detect in wine, and although many wine professionals continue to believe otherwise, others have taken the scientific evidence on board. Steve Charters, a Master of Wine who teaches at the School of Wine & Spirits Business in Burgundy, is unequivocal about volcanic wines: “Volcanic wines play into contemporary tropes about terroir, and despite what viticulturists say, this often equates to geology/soil and its companion minerality—even though we know that vines cannot transmit a taste of the bedrock into the vine.”

But volcanic conditions can contribute to the character of wine in other ways. Rocks don’t retain water (unlike clay, for example), and many of the volcanic vineyards are on slopes, where water drains quickly.

___

As a result, Szabo says, the vines planted in these regions tend to be “semi-parched, semi-starved vines that produce less fruit, smaller bunches, thicker grape skins (where most aromas and flavours are stored), and yield more deeply coloured, concentrated, structured, and ageworthy wines with a wide range of flavours.”

While the age, structure, and composition of rocks and soils can contribute in this way to the character of wine, they are only one influence. Climate is arguably more important, yet volcanic vineyards are found in many different climatic conditions. Some are on islands, such as Madeira in the North Atlantic and Pantelleria in the Mediterranean, while the vineyards of Auvergne are in the centre of France. Some, such as those in Alsace, are in cool areas; others, such as most of Chile’s, are warm.

Of course, grape varieties also define wines, and many in volcanic regions of Europe are indigenous: carricante and nerello mascalese on Mount Etna, for example, and assyrtiko on the Greek island of Santorini. And then there’s fermentation, which has a major influence on the final flavours and style. As Andrew Jefford, one of the U.K.’s most prominent wine writers, notes, “Fermentation changes everything. None of the rock evangelists’ assertions are valid for unfermented grape juice.”

Faced with so many influences on the style, flavour, and structure of any wine, the common presence of a volcano—active, dormant, or extinct—seems to recede into the distance. Moreover, growing conditions created by volcanoes vary immensely in their composition, structure, and age. Szabo also notes that there is no one style of volcanic wine and that the category is “more of an extended family of wines.”

In the end, it might not matter to most consumers whether or not a wine is from a volcanic region. These wines come in diverse styles, even if, like many wines from non-volcanic regions, they tend to be more intensely flavoured and fuller bodied than delicate and light. The volcanic connection is clearly important to many producers as a marketing strategy, but there is little agreement whether it shows in the wine itself.