Master Glover Daniel Storto

Haute handiwork.

There’s no mistaking which industry brought the boom to Gloversville in its early 20th century heyday. The veterinary hospital is called Glove Cities. The football team is the Glove Cities Colonials. The insurance company’s name is Glover Insurance Agency and its icon is a glove. The name itself, of course, shouts the town’s rich history of glovemaking from the rooftops. In its full bloom, there were 750 glove factories humming with industry. There were more gloves made here than in the famous glovemaking regions of France like Millau and Grenoble. An observer back then might tell which colours were in vogue each season by what colour the Cayadutta Creek ran. The air buzzed with the high-pitched whine of sewing machines and carried the unmistakable scent of leather. But just as clear as its history is how quickly it has slipped away. One would be hard-pressed to find any living trace of these decades in this small town in upstate New York, whose Main Street is mostly empty and through which the Cayadutta now lazily trickles.

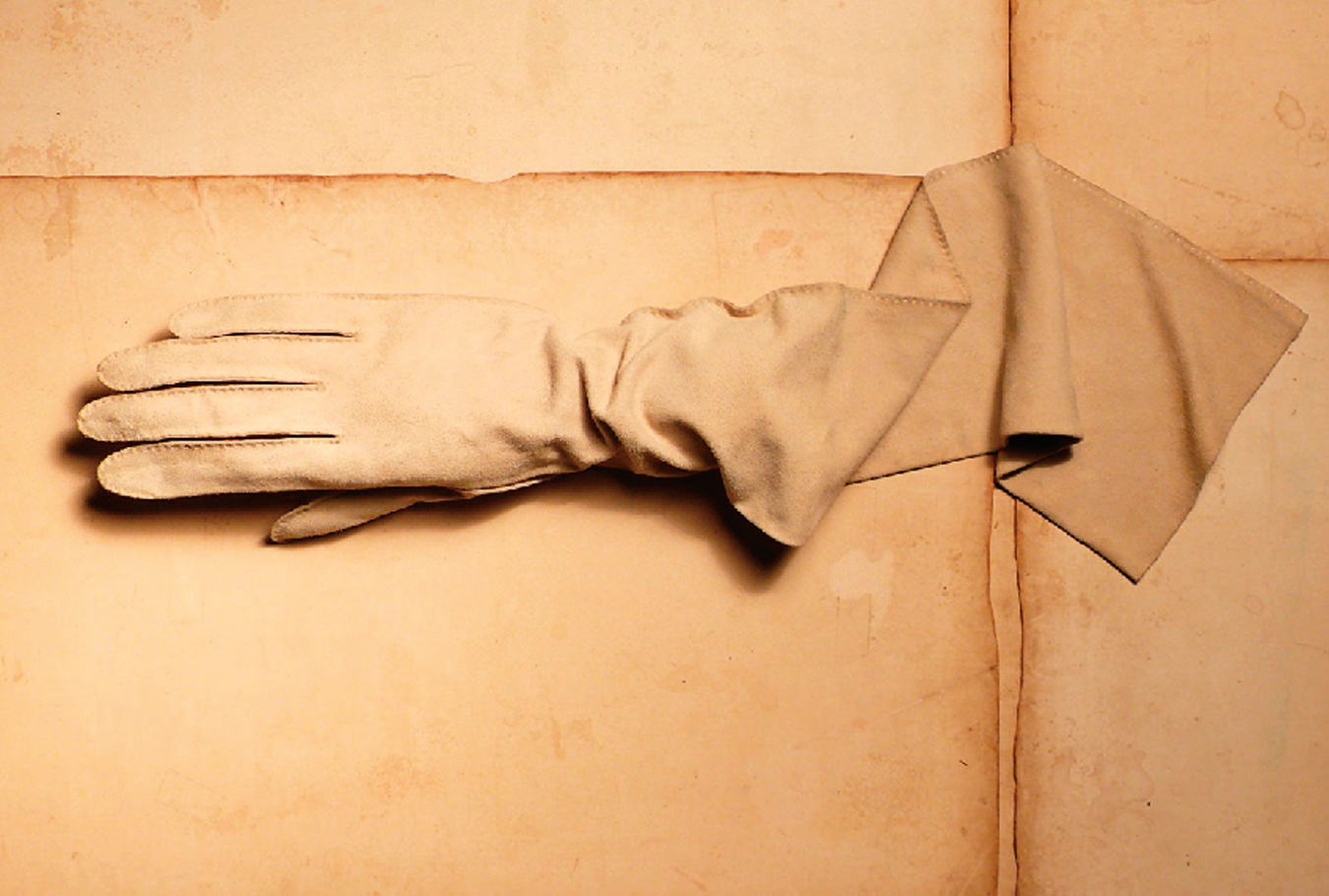

Besides the names and the crumbling, hollowed-out factories caked with pigeon dung, the only record of the past is a sliver of a storefront next to the Glove Theatre on Main Street. There, the light is kept on. It’s small, not much larger than a walk-in closet, and artfully cluttered. Glass cases hold tiny model hands and a small antique desk holds all manner of strangely shaped metal dies. Hundreds of hand-shaped paper patterns hang on a rack. They might look like so many useless sheaths to an uninitiated eye, but to a glover these are the hallowed paper patterns by which gloves are made. This is the store and workshop of Daniel Storto, the last glover of Gloversville.

Storto is a spry and fashionable 61-year-old with a devilish grin, thick-rimmed black glasses, and a trim goatee. He is, perhaps needless to say, not from around here. Three generations ago, the Stortos lived in Francavilla al Mare, a small seaside town in Abruzzo, Italy, where Storto’s grandfather, Antonio, was an artisan shoemaker, back when artisan wasn’t yet necessary to specify. Two generations ago, the Stortos were settled into Toronto’s Yorkville, where young Daniel learned to hand work leather from his grandfather and took to making clothes as if the skill was genetic. By 16, he was selling his own handmade designs in Toronto under the label “Daniel S.” By the early 1980s, he had stumbled across the thing that would come to define his early career. He called it “evening swimwear”. It was a concept few had heard of and soon Storto was taking the Greyhound from St. Patrick Station to New York, where editors like Bobbi Queen, the fashion editor of the influential WWD, and another kingmaker, John Fairchild, lost their minds for a tic-tac-toe themed swimsuit. But the bathing suit could only get him so far, and his mind began to linger on the accoutrements. Storto had begun to sew gloves to accompany his whimsical creations. Even as he accepted—and then quit—a series of increasingly corporate jobs, as creative director for Jantzen Swimwear and Cole of California, his mind returned to gloves. He had never been animated by commercial success or money. He disliked the corporate world, preferring to work with his hands. He was an artisan, like his grandfather, not simply an automaton with a heart.

Eventually, he found himself drawn to Hollywood. Soon after arriving in Los Angeles in 1982, Storto marched into famed costume designer Bob Mackie’s Hollywood office with a violin case full of his gloves. He pulled out pairs with complicated knots, tassels, and fringes. Soon, Storto was Mackie’s hand man. Whenever Mackie needed to dress Cher—who he simply referred to as Her—it was to Storto he turned. In this capacity Storto made some of the most iconic gloves of Hollywood at that time. Rocky Balboa’s fingerless gloves? Storto. Meryl Streep’s long elegant gloves in Death Becomes Her? Storto. Nicole Kidman, Madonna, and Whoopi Goldberg have all worn his gloves.

But it wasn’t from Hollywood that Storto came to Gloversville. In 1998, Storto moved to Antwerp. He had transitioned from making gloves for movies to making gloves for runway, collaborating with designers such as Alexander McQueen, Olivier Theysken, and Dries Van Noten, whose headquarters were in Belgium. He was married and had a young son, André, named after the French haute couture designer Adeline André. He had to make a serious decision: did he want to raise his son as a European or as a North American? He decided on the latter. In 2001, he moved his family to New York but couldn’t afford Manhattan. Yonkers lacked romance but Gloversville, which he had read about in glove history books, didn’t.

It lacked, however, nearly everything else. The town had seen a steep decline. Cheaper manufacturing and changing fashion had been the 1–2 combination that levelled the town. When he arrived, Storto found only three glovers still extant. He set about collecting both the tools of the trade—the many formed dies, the steamers, the stitchers—and compiling the quickly fading knowledge. He gathered the stories, the old photographs, the memories he knew would soon vanish. What Storto does today is much different, more intimate, than the type of glovemaking Gloversville was known for. Storto displays black-and-white images of rooms full of scraps and smiling men stamping out glove shapes. Framed photos he keeps in the back of his shop depict scores of employees outside a factory, now abandoned, a few blocks away. There were, back then, teams of sewers, finishers, and specialty cutters. Storto is a one-man band; he makes gloves completely by hand. So, it’s a nod more than a bow to the history of Gloversville. But if that history is hanging on by a thread, there is no better man with a surer hand to hold the needle than Daniel Storto.