Nature’s Path

Food for thought.

It’s April 6, 1990—a big day for Nature’s Path. The organic food company founded in the mid-eighties by Arran and Ratana Stephens is about to open its first manufacturing facility in Delta, British Columbia, a small enterprise taking a vital step to self-sufficiency. The B.C. Minister of Agriculture is scheduled to be there for a photo op. It will be a feel-good media story—a sign of success for homegrown B.C. industry. If only Arran Stephens can get the damn machines to work.

They will not. No photogenic cereal is coming down the conveyor belts. Unlike Ratana, his wife and long-time business partner, Arran is an impulsive sort. In his eagerness to be free of restrictive and unsatisfactory packing and manufacturing arrangements, he has set up the new Nature’s Path factory without fully understanding how to run it. Now it’s showtime, and cameras will soon arrive to record a whole lot of nothing.

Arran sends an employee to a nearby supermarket on a mission: clear the shelves of a leading brand of corn flakes (Arran will neither confirm nor deny that the box featured a brightly coloured cartoon rooster) and bring them back to the factory. The store-bought flakes are sprinkled over the idle conveyor belts just in time for the photo op. Smiles and handshakes all around. The pictures look great.

Today, the picture of Nature’s Path requires no such trickery. The machinery is rolling now. That little organic breakfast cereal company has become a serious player with over 500 employees and more than 100 products, ranging from cold and hot cereal to granola bars, pancake mix, frozen waffles, and even an apparently rehabilitated version of those toaster-friendly pastries most of the world calls Pop-Tarts. Nature’s Path has muscled its way into an industry that had long been considered notoriously difficult to crack. According to David Ian Gray, owner and principal strategist at DIG360 Consulting, strategy has been a Nature’s Path strong point: “Consistent vision, a unique point of view in the marketplace, betting on the right trends,” says Gray, listing the company’s strengths. “Also, the ability to sell lots of granola without seeming granola.”

Under the feet of giants, Nature’s Path has made a fast break to the big time.

How big, exactly? Arran and Ratana Stephens will not disclose numbers about their privately held company. But the figure recently quoted in Business in Vancouver magazine—which ranked Nature’s Path as the fifty-second largest private company in B.C., with 2012 revenues of $230-million—is, according to Arran, “low.”

To put that in perspective, Kellogg’s reported 2012 revenues of over $14-billion (U.S.). Still, Nature’s Path is making a splash in the industry cereal bowl, now the number-one organic breakfast cereal company in North America. The website MrBreakfast.com lists Nature’s Path among what it calls “The Big 8” in the breakfast cereal business. Once upon a time, any discussion of the industry would focus solely on the Big Four: Kellogg’s, Post, General Mills, and Quaker, companies that had long succeeded in crushing any attempted incursion into a global cereal market currently estimated at $30-billion (U.S.). Now it seems the list has been expanded. Nature’s Path is crowing with the big roosters.

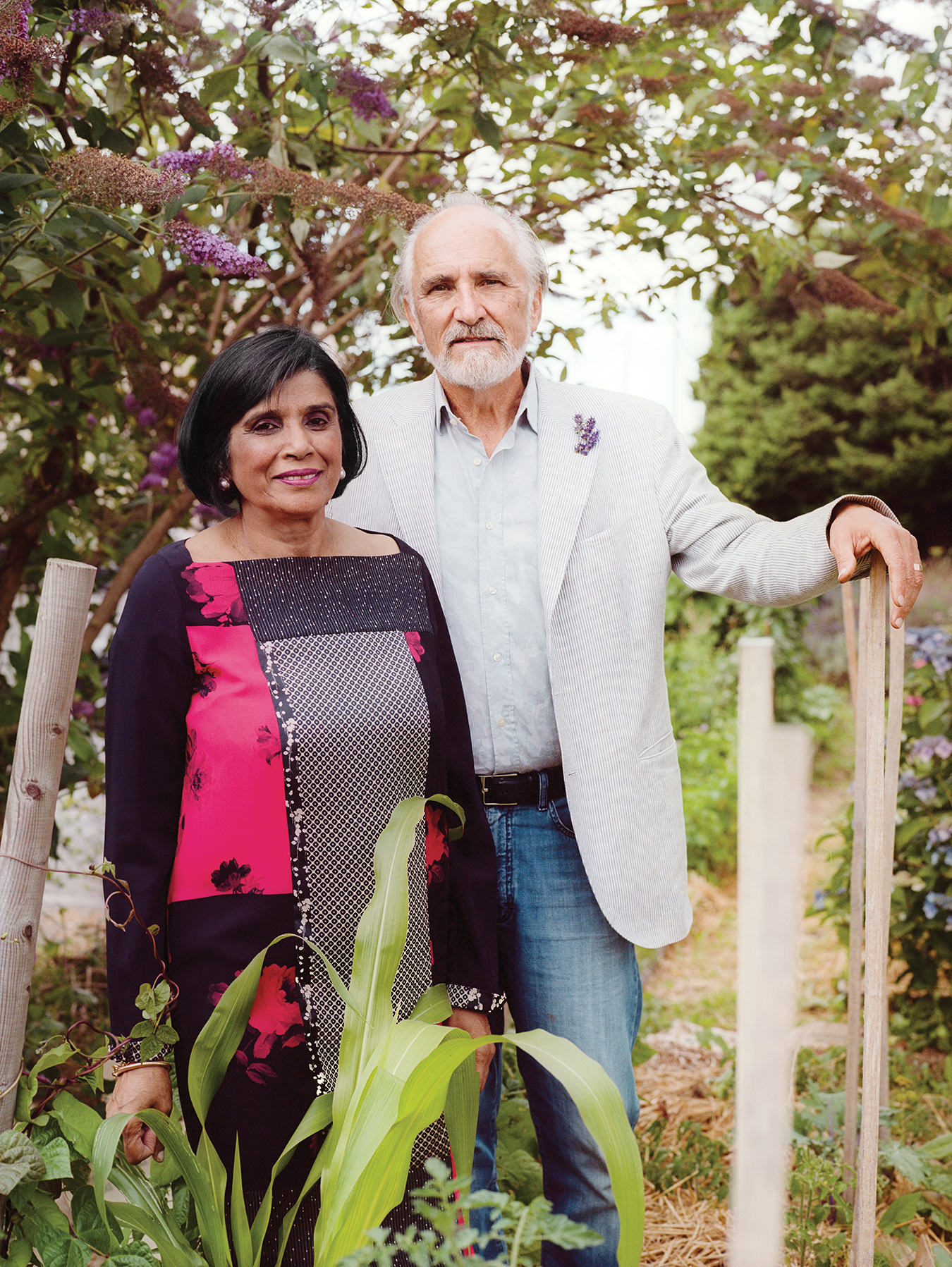

But Nature’s Path is hardly the Stephenses’ first pioneering venture. The couple have been on the cutting edge of organic food retailing since the movement’s beginnings. And although their 44-year partnership did not begin as a business arrangement, it was indeed arranged.

Arran Stephens was born in Duncan, on Vancouver Island, where his father, Rupert, farmed organically before people understood what that meant. (In 1951, Rupert Stephens wrote “Sawdust Is My Slave”, an article first published in The B.C. Farmer, detailing his use of sawdust as mulch.) Arran’s Scottish paternal grandfather had been part of the British Raj, his grandmother Indian. In February 1969, Arran was living in an ashram near Delhi, pursuing a course of meditation and spirituality. His teacher recommended that he meet another of his students, a young woman from Uttar Pradesh. Arran and Ratana were introduced, and Arran had dinner with her family. Two weeks later Ratana wrote to their teacher and said that if a marriage was his will, she was agreeable. Arran felt the same. Shortly afterward the couple were married. “It was an arranged marriage,” Arran says, “arranged by our teacher.”

It wasn’t a match Ratana’s family would have chosen. As a member of the Khatri, one of India’s highest castes, Ratana was expected to marry a suitable match. Foreigners did not rank. “Your daughter has married a cobbler,” some relatives taunted the family. Ratana’s father did not attend the wedding, although he later apologized for his misgivings. (“I went and touched his feet,” Arran says, “and that did the trick.”) But, for some time, Ratana’s family still told the story that Arran was a Khatri from Kashmir whose mother had been white.

Back in 1967, before making his second trip to India, Arran had opened the Golden Lotus restaurant on the corner of West Fourth and Bayswater in Vancouver’s hippie hotbed, the Kitsilano neighbourhood. Arran and Ratana returned to the restaurant, which had become a nexus for like-minded sixties people—draft dodgers, vegetarians, activists. Business was good, except that it wasn’t really cool to call it business. Arran and Ratana toiled for the self-imposed wages of $1.50 and $1.00 per hour. “The feeling back then was that it was food for people, not for profit,” Arran says. “Everybody would be boss. Eventually we got tired of all the politics.”

The couple sold the restaurant for just $2,500. Their next venture, in January 1971, was Lifestream, selling natural foods at the corner of West Fourth and Burrard. It was immediately clear they had identified a market. “Business doubled every year,” Arran says.

Nature’s Path is making a splash in the industry cereal bowl, now the number-one organic breakfast cereal company in North America.

But once again the intersection of counterculture ideals and business reality would prove troublesome. To Ratana’s dismay, Arran offered a half-partnership to a friend who lived downstairs. Later, another partner, a mechanic, came on board for an investment of $33,000. The relationships soon went sour, and the couple were unable to reach a deal to buy their partners out. Despite having started a booming enterprise doing millions of dollars of business, employing over a hundred with a number of Vancouver locations, a wholesale bakery, and a Toronto wholesale operation, the Stephenses sold Lifestream in 1981 for a modest sum. “We didn’t know what multiples were,” Ratana says. “We didn’t know what price the business should be sold for. It was sold very cheaply.”

“We didn’t even have a lawyer, which was the stupidest thing,” Arran says. “We learned a very valuable lesson.” Ratana nods. “No partners.”

The couple did retain one element of the business. Ratana had been running two vegetarian restaurants, each called Mother Nature’s Inn, out of the back of Lifestream locations. Under her management they had become more profitable than the Lifestream stores themselves. Upset over their previous business deals, Ratana had gone back to school and taken a securities course, in the process developing a more practical approach to doing good work and conscious capitalism. “It opened our eyes to profit and loss,” she says.

“You cannot do all of the altruistic and idealistic things unless you make profit,” Arran agrees.

“You can’t provide job security. You can’t grow, you can’t exist,” Ratana takes up.

When Nature’s Path was finally born in 1985, it was Arran’s project. Ratana says, “We had very different approaches. He is more of an entrepreneurial type and I am more practical. I found it was better if we had separate ventures.”

Nature’s Path began by selling frozen sprouted bread. The need for freezer space, which was scarce, made it a complicated product to market, and Arran began to think about more shelf-stable products. He developed four varieties of organic breakfast cereal without chemical additives. At the time, there were no industry standards for the organic category. “I asked our co-packer [a.k.a. contract packer, a company that manufacturers and packages retail products for small firms] if he was following organic standards,” Arran says. “He said, ‘Organic, schmorganic. Anything with a carbon molecule is organic.’ ”

Thus Arran’s somewhat impetuous 1990 decision to set up a Nature’s Path manufacturing facility in Delta. “I really didn’t know how to run a factory or maintain it,” Arran admits.

“It was supposed to be a turnkey operation,” Ratana says. “It wasn’t.”

As of 1991, the Nature’s Path operation was losing money; the factory was subsidized by Ratana’s restaurant profits. Arran was ignorant about maintenance and quality assurance. “We were shipping as much out to the hog farms as we were to be sold [in stores],” he recalls. One day he did not have enough money to make the payroll. He needed help. “If I come on board,” Ratana warned, “no partners.”

Within six months, Ratana had the Delta factory running profitably. (“Hiring a mechanic was important,” Arran says. And this time they didn’t make him a partner.) With Arran as president and Ratana installed as chief operating officer, the Stephenses were a team again. And Nature’s Path was headed straight uphill.

Over the years, attempts to crack the lucrative breakfast cereal market had been reliably crushed by the titans that control the industry. Nature’s Path found a way in by approaching from an entirely different direction—not sweeter, nor cheaper, nor pitched by a cuter cartoon bunny. “They found a unique position that resonated with growing consumer concern around health and wellness,” says DIG360’s Gray, “while marketing, packaging, pricing, and distributing to retail as successfully as the big guys.”

“I always believed that someday organic would become mainstream,” Arran says. “I felt it was my life’s mission to make it happen. We found a niche, got our toe in the door, then a foot, then a leg. We’re like the camel that gets its nose in the tent.”

A steady stream of massive passenger jets sail low over Richmond, a B.C. industrial corridor—a strip that is home to both Nature’s Path and the glide path to Vancouver International Airport. In a small garden out back, Arran is proudly pulling up some large, lovely turnips as gifts for a visitor. “He is still very hands-on with everything, even though the business has grown so much,” says Nature’s Path team member Kyla Hochfilzer. “As their kids get more involved, it’s a bit of a struggle for him to step back, delegate, and let others take over.”

Today he is sticking his head into the test kitchen where Roy Tam, director of research and development, is baking up a new product of crispy rice, flakes, and crunchy balls of puffed corn. One version has cinnamon, another honey. “Smells wonderful,” says Arran, tasting the still-warm mixture from a baking tray. Roy and his team are hoping for more hits like Pumpkin Flax Granola, an Arran recipe that has become the company’s bestseller. Another popular choice, the chocolate-laden granola mix called Love Crunch, was also a family affair whipped up by the couple’s eldest son, executive vice-president of sales and marketing Arjan Stephens, and his then-fiancée, Rimjhim, for their wedding guests. The company makes a food bank donation for every bag sold. (In addition to their son, the couple’s three daughters are involved in various facets of the family business: Jyoti carries the title director of human resources and sustainability; Gurdeep is a spokesperson and asset manager; and Shanti, along with her husband, heads up Manna Organics out of Chicago, selling the same sprouted bread Arran first made as a Nature’s Path product.)

Breakfast cereal has long had a lousy nutritional reputation. “They’re trying to improve,” Arran says of the industry giants, “and we’ve caused them to improve. They’ve gone from denatured grains to more whole grains. But even though they say whole grain, they take out the germ, whereas we use everything. The reason why they take it out is because it gives you a longer shelf life, but it also takes a lot of the nutritional value out. Some of our competitors have a much longer shelf life.”

Nature’s Path also pays a price in higher ingredient costs. “We pay double what our competitors would pay for ingredients,” Arran says, “because we’re buying certified organic. The only way we can survive in this business is through having the most efficient plants.”

“And innovation,” Ratana adds.

One innovation: faced with a shortage of suppliers caused in part by the greying of Canadian farms as farm kids look elsewhere for opportunity, Nature’s Path has embarked on a sort of Prairies sharecropping program. “We started buying some farmland in Saskatchewan,” Arran says. “We’ve contracted with two farm families who are already there, skilled organic farmers who are just farming our additional acreage along with their own. They get two-thirds of the crop and we get one-third. And then we offer to buy it back from them at market rates. In both cases they were able to bring their sons back from the oil fields.”

The breakfast cereal industry has long been infamous for its high margins. A 2008 Toronto Star chart showed the ingredients in a typical box of cereal made up only 2 per cent of its total cost. In recent years, margins have been driven down by the rise of generic supermarket labels, forcing the big companies to cut prices in order to compete. For a company like Nature’s Path, there is big money to be made manufacturing products that will appear under supermarket labels, but the Stephens have avoided doing so. “We have turned down hundreds of millions of dollars in private-label business,” Arran says, “because we want to protect the integrity of our brand. When you get into generics, the absence of a brand means price becomes your brand, and it’s a downward spiral. We want a legacy brand.”

If the Stephenses were a little slow to start focusing on business essentials, they feel it has given them one advantage: idealism has fuelled their perseverance. “The sense of mission was always there,” Ratana says. “The business sense took a while.”

Today, that sense of mission is most clearly expressed on the issue of genetically modified organisms. All Nature’s Path products are labelled as certified organic (which does not allow for GMOs) as well as Non-GMO Project Verified. Among other things, the company is helping to fund and promote the film GMO OMG from director Jeremy Seifert, and Nature’s Path has led a fundraising drive to help get the documentary into theatres. “It’s a beautiful, lyrical film about the land, farming, food supply, the politics of food, and the takeover of our agriculture by a few monolithic multinational companies,” Arran says. (A fall release date for the film has yet to be confirmed.)

Additional Nature’s Path projects include the Bite4Bite food bank donation program, the EnviroKidz Initiatives for endangered species, and Gardens for Good, which promotes community gardens.

Aron Bjornson of Salt Spring Coffee has watched the company’s activism for years. “I remember sitting on the Vancouver Food Policy Council with Arran when it was in its first year,” Bjornson says. “His mission was to get the City of Vancouver to adopt policies that support organic agriculture, and for the City to only buy organic food. He only lasted a handful of meetings when he realized that this item was not the top priority on council’s work plan. I respected his focus.

“I always believed that someday organic would become mainstream,” says Arran Stephens. “I felt it was my life’s mission to make it happen.”

“Nature’s Path is deeply committed to organic foods,” Bjornson says. “With worldwide sales, this is no small investment. It takes deep dedication to building a strong supply chain—connecting with organic growers and really understanding the commodities market to make sure that organic supply is consistent. None of Nature’s Path competitors have be able to do this at the scale they have.”

Recently the company’s activism gained international recognition. At a September 25 gala in Baltimore, Nature’s Path will receive the 2013 Organic Leadership Award from the Organic Trade Organization (the industry’s most coveted award), after being chosen over 26 other nominees.

But, as the couple learned the hard way, healthy campaigns are not possible without a healthy bottom line. Nature’s Path is still in the ring with some big retail bruisers. Challenges loom. Could the company fall victim to its own success in raising the bar for breakfast cereals? “I see parallels with beer,” DIG360’s Gray says. “Craft beers have really grown from a small base. But Kokanee and Molson Canadian are still the major sellers. Pretty soon the big guys start buying the larger independents, and they start adding new lines of their own. The question for Nature’s Path is where will the growth come from as the mainstream moves into their space?”

Arran believes the company is well positioned in the fastest-growing sector of the retail food industry. “When we started in ’69, total North American sales for the organic food industry was probably not more than two to three million,” he says. “Today it’s a $63-billion [U.S.] dynamo [globally]. It’s outstripping the pace of traditional food industry by many times.”

And, what, ultimately, would the Stephenses recommend as the true key to business success? “An arranged marriage,” Arran says.

“Oh, please,” Ratana groans. But they’re both laughing.

What is Organic?

Organic is natural, but natural is not necessarily organic. And certified organic isn’t necessarily 100 per cent organic. Labelling has become something of a minefield, with recent controversies roiling the booming organic industry. A quick rundown:

In Canada and the United States (the Canada Organic logo and the USDA Organic logo are considered equivalent), certified organic products must conform to a set of guidelines. Organic products cannot be grown with synthetic pesticides. They cannot include GMOs, be treated with ionizing radiation, or be fertilized with sewage sludge.

To be called organic in the United States, a product must be made with all-organic ingredients—unless those ingredients are found on a special list of over 250 exemptions, including animal enzymes and gelatin substitutes like agar and carrageenan. Thus, a certified organic product might contain up to 5 per cent approved non-organic ingredients—a standard also observed in Canada.

In Canada, controversy has resulted from the lack of independent government testing of organically labelled products. After filing a Freedom of Information Act request, the CBC discovered that, in 2011, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency found synthetic pesticide residue in 24 per cent of the certified organic apples they tested. Further controversy in the U.S. was sparked by a 2012 New York Times article claiming that giant food companies were exerting political pressure on regulators to weaken the definition of organic.

“Natural” is a different and less stringent retail category. As long as a product uses no artificial flavours, colours, or preservatives, it can label itself “natural”—even though its manufacture involves the use of synthetic pesticides, artificial fertilizers, irradiation, and GMOs.