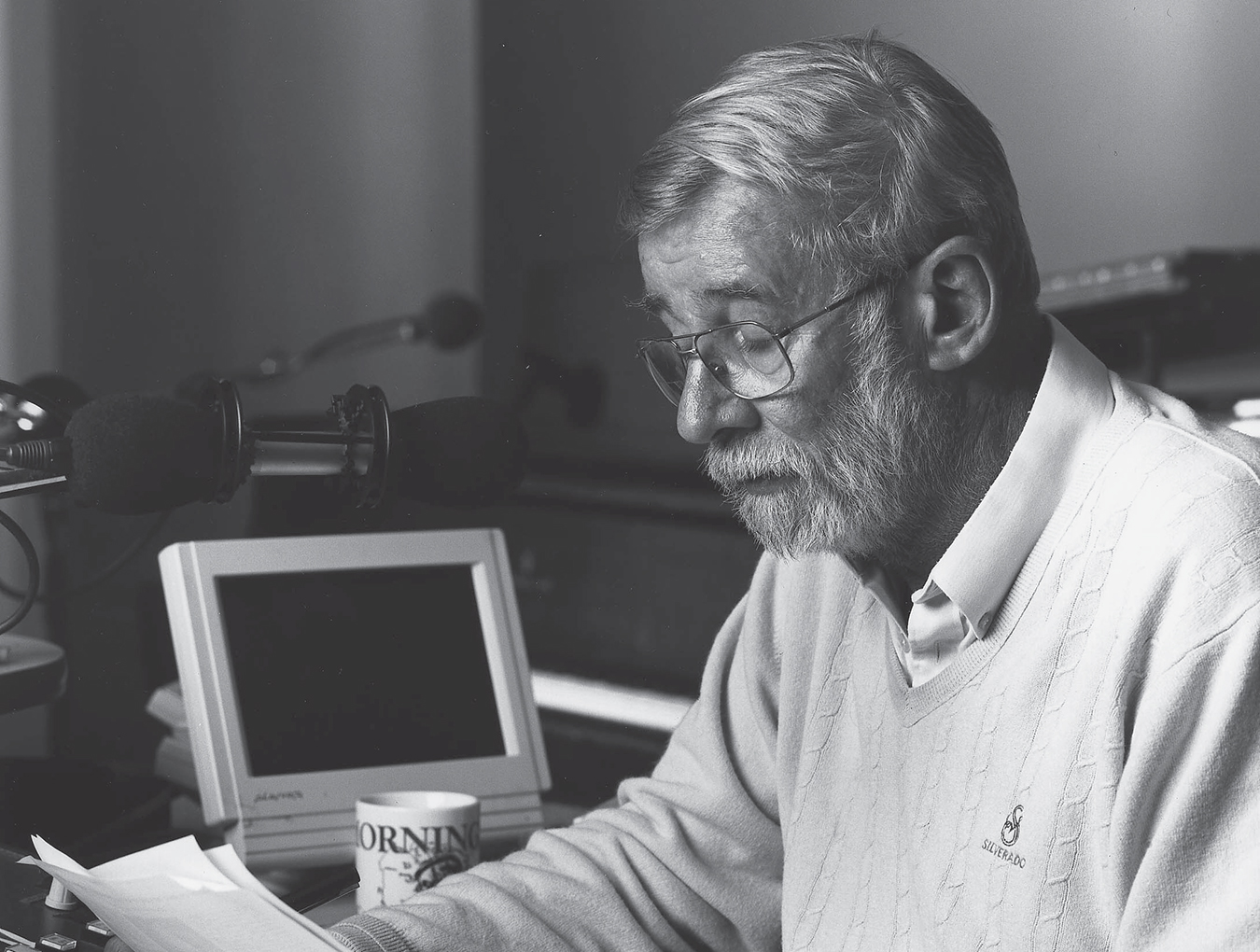

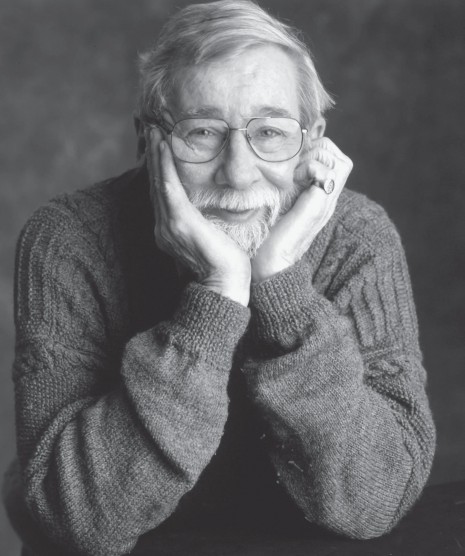

Peter Gzowski

The art of the interview and the great man's legacy.

The classic Peter Gzowski story goes like this: “I sat for ten minutes in a Zellers parking lot in Halifax, with the car running, listening to the end of one of his interviews,” writes Michelle Daignault. “Finally, when it finished, I shut off the car and stepped out chuckling. Six other people around me were stepping out of their cars at the same time. We realized at once that all of us had been listening to Morningside together and started talking about the show. It was a magical moment.”

That’s all a radio host could ever hope for, really.

Peter Gzowski’s death in January, at the age of 67, touched off an outpouring of shared memories across Canada. We heard from devoted listeners like Michelle in Halifax, loyal colleagues like Shelagh Rogers, his favourite guests, like Dalton Camp, Rick Mercer, and Steven Page of the Barenaked Ladies. I was familiar with all that, felt the same sadness. At the same time I was overwhelmed by recollections of the unusual experience that set me apart. Elm Street magazine could dub me “Gzowski’s Hip Replacement” on its cover, if it wanted. The truth was, his old bosses at CBC Radio One contracted me in the summer of 1997 to help Michael Enright be his slayer, in the sense that we were to dazzle listeners into forgetting how much they missed him. We hoisted our dull axes.

I didn’t know it was akin to a suicide mission when I became co-host of the successor show This Morning. But how could I refuse? Just to be asked was the single greatest honour of my life. I was a pup of a radio host, 31 years old, working at a privately owned station in Montreal that always thumped Morningside in the ratings despite its obsession with angry Anglos suffering post-referendum angst. At home, my bookshelves were laden with Gzowski titles, notably the multiple Morningside Papers. The books were gifts from my father, a great fan of the unpretentiously intelligent radio legend. One inscription dates back to my time at CBC Radio in Quebec City: “From the Quebec Community Network to Morningside?…Love Dad. X-mas ‘89.”

When that far-fetched scenario eventually came true, I showed it to Peter Gzowski. He chuckled, pulled out a black felt pen, and added to the bottom of the page: “Hey, he was right, eh?—except for the name! Way to go, Avril.”

I got his autograph. We had just done an interview on This Morning about his memoir The Morningside Years. There had been grumbling, in the wings, that the last thing the new show should be doing is reminding our listeners just how much they preferred Saint-Peter to us. But I was keen for a chance to talk to a living legend about our shared love of radio. Listening back to the tape, I sound unbearably giddy at the thought that he might teach the elusive technique that compels listeners to stay in their cars until the end of the interview.

Gzowski: “I think you can easily tell as it’s happening. Usually, something takes off or the guest gets really engaged in the questions you’re asking or loses a bit of control or there’s a bit of emotion or some fabulous insight. Or an energy … You know when it’s happening … I think, by and large, you can certainly tell when it isn’t working. Woops!” he breaks into laughter.

He admitted he had been gathering material, on his computer, for a book on interviewing. If ever his family decides to root it out for publication, one can bet it won’t cover the template of tips journalism students memorize from the how-to texts. By-the-book, Peter Gzowski would have flunked.

Not Barbara Frum, who hosted As It Happens on CBC Radio One before moving on to The Journal on television. “Her mastery of radio was unparalleled,” Gzowski once wrote. Her mantra was, essentially, ask the question, make it snappy, and get out of the way.

Gzowski’s was, supposedly, “I steer, you paddle.” Why, then, were Gzowski’s questions, more often with writers than others, 150 words long? (Seriously, check the transcripts yourself!) His fans stayed tuned for a treasure hunt when he let the canoe go in circles and nearly tip as he clambored his way to the front bench to sit beside his paddlin’ guest. In The Private Voice, he described his interview with Northrop Frye.

“I confessed to my own discomfiture in his intellectually intimidating presence, and asked if, as I had read in a magazine article, it was a common phenomenon.”

“He gave the answer interviewers dread. ‘Yes.’”

If you are going by the unwritten rules of interviewing, that wasn’t a successful question. But we’ve learned something here about the guest, the host, the dynamics of intimidation.

The school marms of strict interview style cringe at the possibility that the question can sometimes be more fun than the answer. Gzowski knew that when he asked things like: “Was Shakespeare constipated, in your view?” Or: “Now, Miss (Alice) Munro, you know that you are among my exalted heroes in the world of literature and I’m a huge admirer of everything you’ve written, including your most recent work, but what I want to know is, are you going to read some more dirty stuff?”

Her answer: “Sorry, no.”

His questions were often what we call closed-ended, or not questions at all. His questions could be triple barreled, like this one which opened an interview with W.O. Mitchell, who had just won an award: “What do I call you now? The Honourable? The Right? No, the Honourable. The Honourable W?” The interview soon gave us the kind of exchange that would strike critics as banal, but fans as a snappy character set-up or conversation starter:

PG: Are you honourable?

WOM: I try.

PG: You’ve always been honourable, in my book.

WOM: I try to be. Like you, I try.

PG: What do they give you? Do you get anything?

WOM: In the way of?

PG: I don’t know, a cheque or a seat or privy.

WOM: Yeah, I got a ribbon and a medal.

PG: Did you?

WOM: Yeah.

The source of most derision, with respect to his on-air style, had to do with what Dalton Camp described as a way of asking questions “the way baseball pitchers get around to making their pitch, with elaborate introductory manoeuvre and circumlocution.” Gzowski just called it babbling. “But I can’t do anything about that,” he wrote. “It’s just the way I talk. I think as I go, and sometimes I do change courses in the middle of a question. Sorry.”

Many people suspected the verbal tic was no accident. Alan Fotheringham’s take on it is a familiar one, “At first, it may have been nervousness. At end, one suspects, it became an ingrained affectation.” Such mannerisms can be affected? Evidently, many believed they could and should.

Even some senior producers I worked with at This Morning wanted me to affect “thinking,” which sounds far more condescending than it is. They encouraged the fresh new voice to sound like the departed veteran, who let listeners into his mind by thinking aloud. They wanted to hear the hesitation of deep, how shall I put it? thought in my, hmmm, phrasing of, oh I don’t know, questions. Like Peter.

Putting the face to the voice.

Similarly, when interviewing a novelist, the same producers did not want me to read the book for insight into how to steer the interview, which was my motivation; but rather to show off to the listener that damned right! I’d read the book just like the ol’ man would have—if he were still around.

I wasn’t the only one experiencing the curse of comparisons. My old show mate Michael Enright was once again facing the same opposition game that marked his tenure the first time he had replaced Gzowski, for one ill-fated year, 1974, on This Country in the Morning. He described it this way, for Maclean’s magazine: “He was warm and cuddly. I was edgy and confrontational. He was rural, small-town Canada. I was urban, big-ugly city. He was Uncle Friendly. I was Mister Meanie.”

Gzowski, in turn, admitted he found Don Harron a hard act to follow. Worse, he was under pressure early in his broadcasting career to sound like the witty and sophisticated Dick Cavett.

After he died, the eulogies poured in. Adam Scott of Ottawa wrote to The Globe and Mail that with Pierre Trudeau and Peter Gzowski gone, “ … nobody seems to have the courage or capacity to follow in their footsteps … too few will offer the sincerest and most needed form of flattery—imitation.”

Believe me, they tried. It can’t be done. Broadcasting is strewn with personalities who feel compelled to imitate those they deem successful. And so we hear one private radio station after the other with morning men aping the vocal mannerisms of Baritone Man! Who’s he, anyway? Not somebody you miss when they’re gone, that’s for sure. Not somebody whose interviews were re-played and celebrated the way Gzowski’s was, both when he retired from Morningside and again, after he died.

The gift he had, as an interviewer, is not one they teach in broadcasting manuals. He just knew the elements of a good spoken story—a narrative with a beginning, middle and end. On radio, the medium he described as second only to the phone in its capacity for intimacy, he would nudge his guests toward the descriptions that took us there, toward the plot points that made us care what happened next. One sensed he had charted the path without the guest even knowing. Like a comic who knows to exit the stage after he gets what could be his last hearty laugh from the audience, Gzowski knew when to stop asking questions: after a brilliant last answer that tied it all up with a bow.

He had help, of course. Producers who rooted out the best talkers across Canada, who pre-interviewed them at length, who prepped them with feedback on what Peter would find most interesting, who wrote up the salient points in briefing notes, who wrote the introductions and suggested questions. Morningside had the CBC’s largest convent of news nuns, a unique breed of mostly white women in their 30’s and 40’s, university educated, well travelled, who worked long hours behind the scenes and sacrificed their personal lives for the reflected glory of serving him (not to be confused with Him).

Even those producers who resented his often pricklish off-air manner, even those who thought he quit daily radio about three years after he lost his appetite for it, knew that the radio show was worth it. Everything Gzowski publicly stood for was worth it, at the time.

“And what of me?” Gzowski writes in the afterword to The Morningside Years. “Was I too … nice on the air, too soft with the bad guys and the politicians and the rich and the famous in general, too, as some people charged—and oh, how I hate this word—unctuous?”

Three years after he left daily radio, the magnetic pull of his legacy compelled CBC Radio execs to call off the futile Peter Who? Mission. They finally hired Shelagh Rogers to take over, and bring back the gentle warmth listeners had missed.

As I write this, the public radio service is forging ahead with renewed commitment to reflecting the Canada that wasn’t as much of a priority on Peter Gzowski’s Morningside, with its celebration of all things homespun. As a nation, we’re mostly plugged-in urbanites, overworking ourselves in multicultural cities and suburbs, competing in a fast paced global society. The topical focus may shift, somewhat, on CBC Radio One. The civility and curiosity Gzowski presented on air will surely live on.

Photos courtesy of CBC Archives.