-

Inside the Chanel ateliers at 31 rue Cambon, Paris, where skilled fingers create exquisite clothing.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

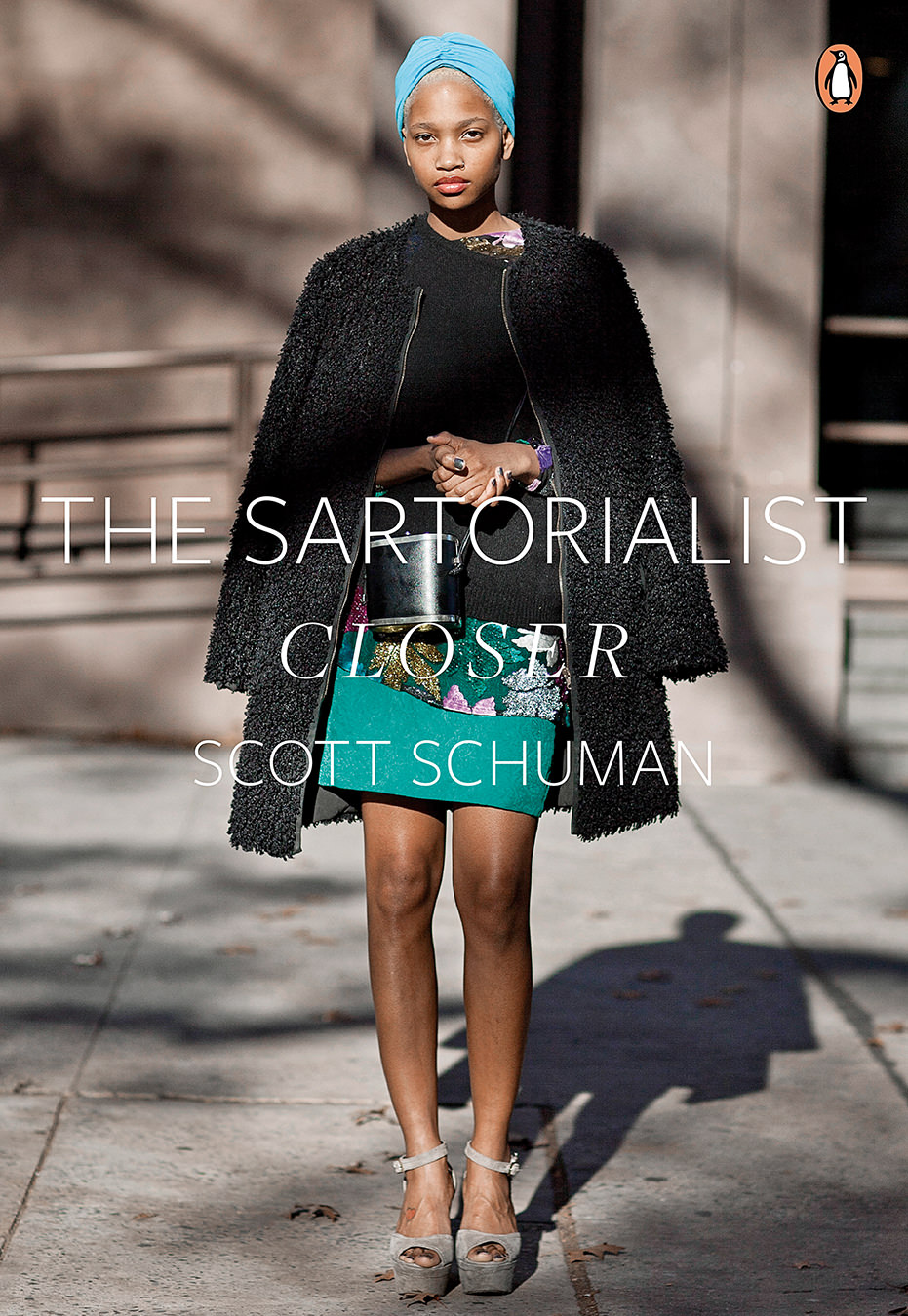

Stitch by Stitch

At 31 rue Cambon, Paris, where petites mains make Chanel’s haute couture.

Songs have been written and movies made about the rooftops of Paris, with their sentinel chimney stacks guarding gleaming zinc roofs, and dormer windows opening into slope-ceilinged rooms reached by spiral staircases. Hands ruled these spaces in earlier times; practical hands in the case of the chambres de bonnes shoehorned in under the eaves, but imaginative hands, too. Most of these skylit rooms are now apartments, but in the past, many belonged to artists. It is still that way at 31 rue Cambon, where, in light-washed ateliers, skilled fingers create exquisite clothing.

If you wanted an address symbolic of luxury fashion, it would be hard to improve on the home of Chanel haute couture, which stands in a narrow street just west of Place Vendôme and north of rue Saint-Honoré. It was here, at 31 rue Cambon, in 1909 that Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel first opened a hat shop, and, some years later, acquired the nearby 18th-century building that is the present address. Here she invented the modern boutique, showcasing what was a quantum leap for fashion in terms of simplicity and comfort. Number 31 was reserved for work and entertainment. At night, she crossed the street, making her way through the back door of the Ritz to the suite where she moved in 1934 and where, in 1971, she passed away.

Every morning, Gabrielle Chanel walked the few steps to her “office”, where staff, alerted that she was en route, had already sprayed Chanel No. 5 on the staircase. Client fittings happened either in the salon downstairs, or upstairs in the area now occupied by Karl Lagerfeld, who in 1983 was named head designer and who, through continual reinvention, keeps the name as fresh and new as it was in the 1930s.

Haute couture is the foundation of the house of Chanel (ready-to-wear only came into being in 1978), and it is in these workrooms that it is born.

Picture 31 rue Cambon in cross-section. Ground-floor entry and three haute couture salons above, which are Lagerfeld-designed in a palette of white, black, and beige—where lyrical notes (the white flowers that were Chanel’s favourites) meet practical touches (the black high-heeled shoes a client can don to check the length of a skirt). Continuing upward, you pass Coco’s famous apartment, with its Coromandel screens, beige suede sofa, and ornate Prussian mirror whose shape evokes a Chanel No. 5 stopper. Moving on past the design studio, you eventually reach the summit, flooded with natural light, large windows looking out on to treetops, pigeons, and roofscape. Here are the ateliers. Haute couture is the foundation of the house of Chanel (ready-to-wear only came into being in 1978), and it is in these workrooms that it is born.

Every July, Chanel presents its haute couture collection for fall/winter, and this past July, the 2012–2013 collection was shown at the salon d’honneur of the Grand Palais, a grand room transformed for the occasion into a camellia-bedecked winter garden. (Each January, the haute couture collection for spring/summer is staged.) Where previous collections had been sexy, this new collection was sensual, with its modest skirt lengths, elegant shift dresses, and modern takes on the much-loved suit. This was a “soft” wardrobe; even the handbags were made of tweed. If past collections had been designed to shock, this one soothed with a delicate palette of grey, off-white, black, and every shade of light pink. “The colour card [has] a little of Marie Laurencin,” commented Lagerfeld. But it was not just the colours that brought to mind the delicacy and femininity of the 19th-century painter. There was gentleness to it, a low-key glamour, immense wearability. Lagerfeld had called his fall/winter 2012–2013 haute couture collection “new vintage”, but the term had nothing to do with making a line-for-line copy of retro fashion. As he commented after the show, “I wanted to keep only the attitude and the spirit, but project it in a different way on the girls of today.” Fabrics are always unique to Chanel and in this collection had been made even more so. Far from being a random assembly of ragbag scraps, his renditions of “patchwork” were carefully curated squares of black, grey, and deep and pale pink tweed with random flashes of gold and silver sequins, all hand-seamed together.

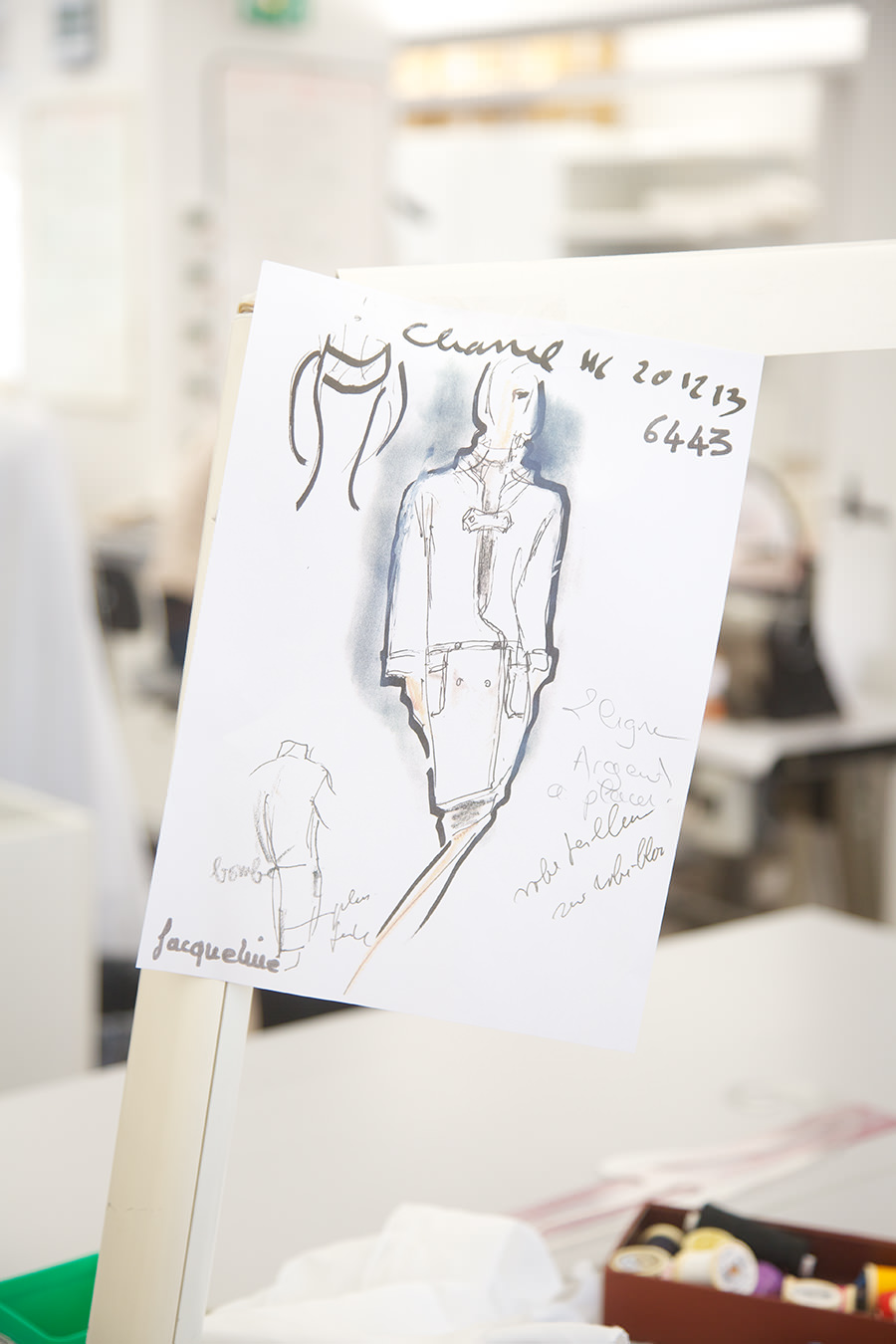

Five days before the show, it feels like the calm before the storm in the tailleur and flou ateliers (tailleur means tailoring and working with heavy fabrics; the lighter-sounding flou refers to more fluid materials). Those who work here are known as petites mains—little hands. At Chanel, Madame Jacqueline, a 15-year veteran with the company, heads the tailleur atelier. Madame Cécile, who has been with the house for a decade, runs one of the two flou workshops. Both learned their métier at couture houses (the former at Chloé and the latter at Christian Lacroix), and at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture.

The atelier tailleur is cool, calm, and white walled, as is everywhere else at Number 31. Bustes stand around like silent observers, narrow blue and red tape delineating arm length, bust, and hip.

About six weeks before the collection of 64 looks was shown, Karl Lagerfeld provided the first sketches to the Chanel ateliers. Casually taped to a lamp in the area devoted to tailleur, one of those drawings is of a suit-dress; hand-written notes state that this is a robe tailleur sur robe bleu, an optical illusion, an example of the designer’s liking for trompe l’oeil. This penchant for fooling the eye means coats entirely embroidered to look like tweed that take nearly 3,000 hours to make (a Chanel bridal gown typically needs 1,000 hours of work). On a table scraps of fabric and an almost complet-ed tab pocket are identified as “6443”—the number of the sketched dress. Nearby, two women discuss and experiment with the exact positioning of two pieces of tweed. Patch-pocketed, a toile of a long coat hangs on a rack, rows of pale red pencil lines indicating subsequent embellishment. Someone rehearses an arrangement of pleats, not with fabric but with finely pleated paper.

The atelier tailleur is cool, calm, and white walled, as is everywhere else at Number 31. Bustes stand around like silent observers, narrow blue and red tape delineating arm length, bust, and hip. A square white bin holds clothes hangers covered in black velvet. White cotton bags conceal finished garments. For a place that makes clothes, the room is surprisingly quiet; the only sounds are conversation and the rare buzz of the sewing machine that is sometimes used to reinforce seams.

Simply put, ready-to-wear is made “flat”, cut from a two-dimensional pattern. Built on a replica of the client’s figure, haute couture literally adds another dimension. Made in the round, the initial sketch is first made up in white cloth, then fine-tuned, and finally cut and stitched in the chosen fabric. Everything at Chanel haute couture is done by hand.

Besides its own ateliers, Chanel also works closely with other workshops, experts in embroidery, feathers, costume jewellery, and the making of fabric flowers. Founded in 2003, this Métiers d’Art branch preserves the ultimate in crafts know-how, celebrating it with annual shows that pay homage to cities or places important to Chanel via collections inspired by Russia, Shanghai, Byzantium, and, most recently, India.

On Chanel’s top floor are the two ateliers, identical in competence and savoir faire, that share responsibility for the flou pieces in each collection. The atmosphere is different behind the door labelled “Atelier Cécile”; the first impression is of small scale, a froth of pale hues, an almost boudoir-like ambience. This is a place of diaphanous fantasies so ethereal that you could imagine them tethered by invisible threads or else, surely, they would drift like clouds out through the windows and across the rooftops.

One petite main works with silk organza pleats, securing them with pins, her own outfit of jeans and tank top in striking contrast to the ball gown of palest pink that is coming together in her hands. Supplied by an outside atelier, Lemarié, and pinned to a clothes hanger, the lengths of pleating in different widths are being cut apart, then stitched to the skirt to create a gown with the gossamer allure of dawn-tinged seafoam.

This is a place of diaphanous fantasies so ethereal that you could imagine them tethered by invisible threads or else, surely, they would drift like clouds out through the windows and across the rooftops.

In a striking example of trompe l’oeil, a long gown at first glance appears to be made from a black flower print on a peach-coloured background. Examined more closely, its “pattern” is black feathers cut with razor blade precision, their individual plumes appliquéd stitch by stitch. On the reverse side of another fabric, decorated with blue and white crystals, and white sequins like scattered elderflowers, massed tramlines of tiny stitches reveal the extent of the work involved. Elsewhere, outlined in gold, black lace is being mounted on silk organza, the intricacies of its pattern extending flawlessly onto the waistband, the kind of cut-and-stitch work that can only be done by hand. Mixed in with the fanciful is the practical. A petite main stitches the cover that will hide an elastic waistband. Baleines, élastique blanc, and élastique noir, the elements that make up the unseen, often complex substructure of haute couture, are stored in clear Perspex boxes. Beside the door, a model stands before a mirror, her pale hair coiled in a chignon, her face makeup-free. Her lissome grey skirt descends to the floor. Two seamstresses adjust her intricately embroidered top, experienced fingers securing the fabric, then pinning in place what look, to the outside eye, like infinitesimal changes.

You may already have your eye on one or a number of daywear pieces, or be seeking something for a wedding or special occasion, or maybe it was simply a coup de foudre between you and those supple wide-legged lace trousers. Here’s what happens. You make an appointment (or you may have already booked one even before you saw the collection). The head of the atelier measures you and creates a buste that is accurate to your last millimetre. Then, well, you love the look, but… Provided they respect Karl Lagerfeld’s original concept, modifications can be made—a hem lowered, a sleeve shortened, and volume added or taken away. Giving advice is part of the service, as is quietly mentioning that someone in your city or social circle has already ordered that same outfit. It’s the ultimate in haute service.

Three weeks to a month later, you try on your garment, constructed in the final fabric but without embroidery or embellishment. Micro adjustments are made, work recommences, and then after a couple of months, your piece is ready. You can order anything that Karl Lagerfeld has ever designed for Chanel—not just from the current collection—and within reason, any piece can be modified over the years, until the time that you hand it on to your daughter or granddaughter. At the house of Chanel, haute couture means fashion that is genuinely heirloom.