Montreal’s Russell Banx Sketches a Profoundly Empathetic Form of Masculinity

A quiet intimacy.

The boys are not all right. Statistics sketch the grim contours of a growing crisis: according to recent data collected by the American Institute for Boys and Men, 15 per cent of young men say they don’t have any close friends. From preschool to higher education, males are many percentage points behind females in school readiness and enrolment in degree programs. In the workforce, men are dropping out more and earning less than they used to. And perhaps most distressingly, men are four times more likely than women to die by suicide.

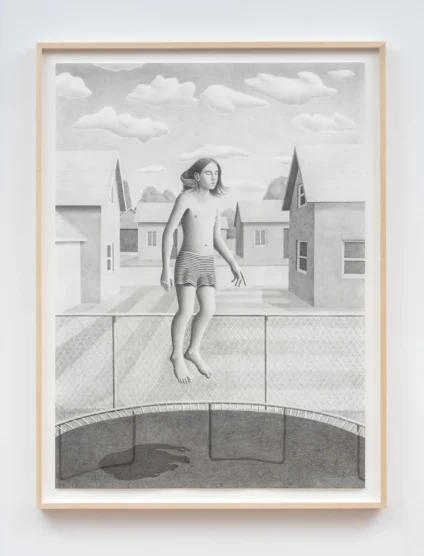

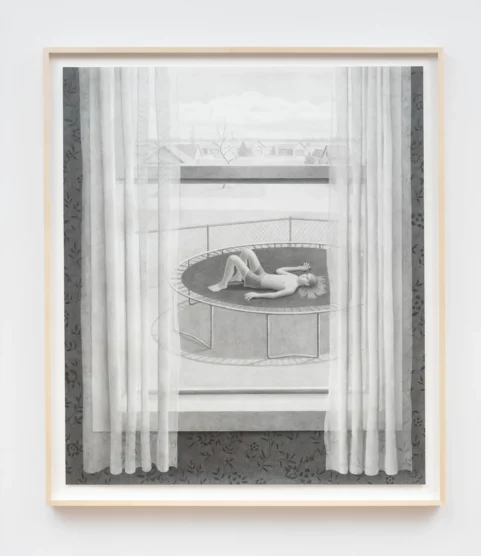

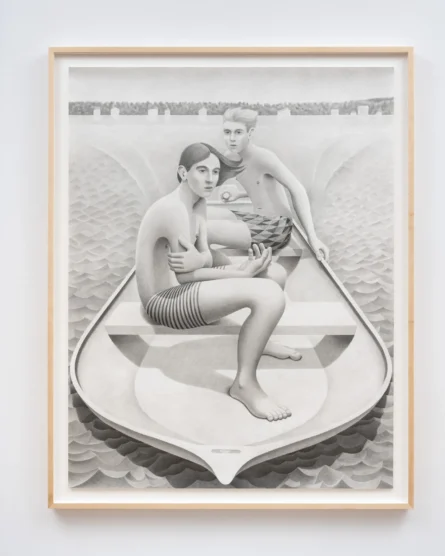

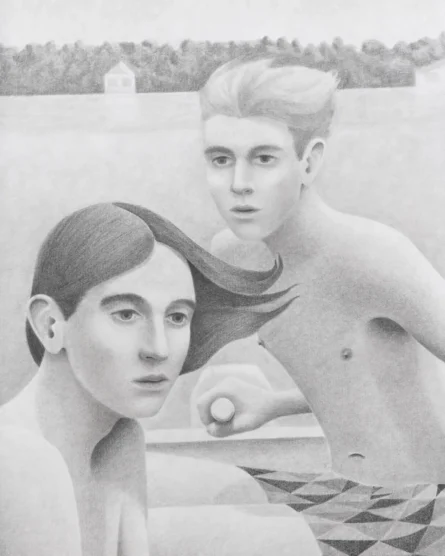

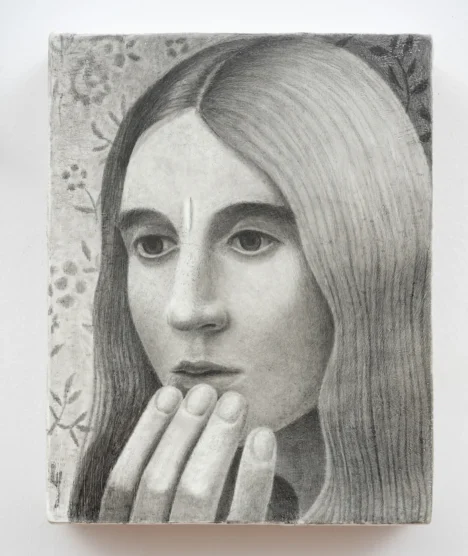

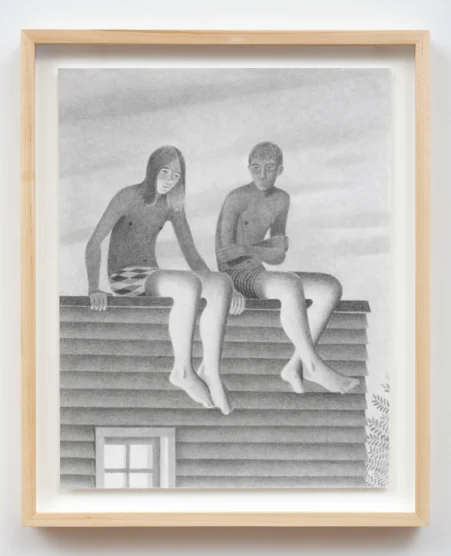

For 38-year-old artist Russell Banx, based in Montreal by way of Leipzig and Toronto, the statistics only confirm a feeling he holds deep in his marrow: that patriarchy is an equal-opportunity oppressor, deleterious to all, regardless of gender identity and expression. In his latest body of work, recently on view at Montreal gallery Pangée in the exhibition Gaze and Gesture, Banx sifts through boyhood memories. In the series of grisaille drawings, he depicts brooding young men stumbling awkwardly through adolescence. While they are physically engaged in the everyday activities of teenhood, their minds are elsewhere, wandering adrift.

“People are always, like, ‘Are these self-portraits?’” Banx says. With shoulder-length blond locks that match those of the floppy-haired figures in his work, the artist understands why viewers might make that connection. “Sometimes they are kind of me,” he acknowledges, “but they’re also a representation of the experience that I saw a lot of boys go through when I was young.”

“I’ve always drawn, and I’ve always found it more connected to my mind and my heart,” he says, describing his pencil-based practice as introspective and therapeutic, similar to keeping a journal. “I started to step away from painting and dive into very simple graphite drawings. It felt more true to who I was. I wasn’t trying to put on a persona. It was just me.”

Banx grew up about 30 minutes north of Peterborough, Ontario, in a small town he describes as “suburbanized cottage country.” Back then, being taunted with homophobic slurs was a common occurrence for anyone who “didn’t live up to the archetypal, typical masculine traits” such as playing hockey, he recalls. “I was always kind of a weird outsider with the boys,” says Banx, who felt most free to express himself among his female peers. “I always desired more from my male friendships when I was younger. It’s like there was this wall that you just couldn’t get through. I think a lot of my drawings now have to do with that disconnect.”

It was through music that Banx was able to bond with other young men his age. Straight out of high school, he played guitar and wrote songs in a shoegaze band that got scooped up by a major record label—and was then quickly chewed up and spat out. “We were writing 250 songs a year, and it was essentially the same song over and over again,” Banx says. “The creativity was just sucked out of the project for me.” He’s reluctant to talk about the experience in too much detail, except to say that “this idea of a band, and the tight camaraderie that is close to family, really informs a lot of the images that I make now.”

Feeling disillusioned and in need of a fresh start, “I left the band and decided that I just wanted to dive right into art,” he says. With youthful confidence that might now be labelled impulsivity, “I decided to move to Germany without really knowing anyone there. And it was fantastic.”

Banx treated his time in Leipzig (nicknamed “Hypezig” or the “new Berlin” in recent years due to its popularity with young artistic types and for being the hometown of influential German contemporary artist Neo Rauch) as a kind of self-directed fine-arts degree. “In my head, I’m like, I’m doing my undergraduate right now,” he says of the artistic autonomy he found there. “I’m just making trash work and figuring out what creativity is to me.”

Going back and forth between Canada and Germany over the years, Banx honed his skills in oil painting, invoking the raw, expressive spirit of the late Irish-born British artist Francis Bacon, who was known for his bleak and brutal canvases. “I was fetishizing paint, like, wild brushstrokes—the typical stuff you would expect from someone who doesn’t really have a nuanced taste in art,” Banx says self-deprecatingly, reflecting on the notion that Bacon is to art what David Foster Wallace is to literature: both geniuses, inarguably, but with their lustre somewhat tarnished because of their ubiquitous appeal among a certain type of chauvinistic cultural connoisseur.

Then, fate, in the guise of a mysterious, mail-intercepting art burglar, caused Banx to abruptly change course. “I applied to UdK in Berlin, and they require you to send a portfolio that is original pieces,” he says, referring to the prestigious German art school Universität der Künste. “I had 25 paintings. I packed them up and sent them, and then I received mail that my portfolio never arrived. So I was like, ‘What?’ I looked at the tracking number, and it said that it was received, and there was a signature. So I sent that, and they were like, ‘Yeah, we don’t recognize the signature, and the portfolio is not here.’”

Stripped of his oeuvre, “I was pretty heartbroken,” Banx says. “And that’s why I made the decision to just move to Montreal, kind of on a whim.” He arrived in 2019 and started his bachelor of fine arts at Concordia University, where he is currently finishing his final semester. The timing turned out to be serendipitous. “I was ready to start a body of work that really made sense to me,” he says. He was beginning to feel discomfort around what he was putting out into the art world from the position he occupied as a white, cisgender man. Many of the terms associated with the style of painting he had been doing “are so associated with idealized masculine traits, like ‘taking risks’ and ‘being daring,’” Banx says. He was ready to file down those sharp edges boxing him into an ill-fitting identity.

What felt most authentic was drawing. “I’ve always drawn, and I’ve always found it more connected to my mind and my heart,” he says, describing his pencil-based practice as introspective and therapeutic, similar to keeping a journal. “I started to step away from painting and dive into very simple graphite drawings. It felt more true to who I was. I wasn’t trying to put on a persona. It was just me.”

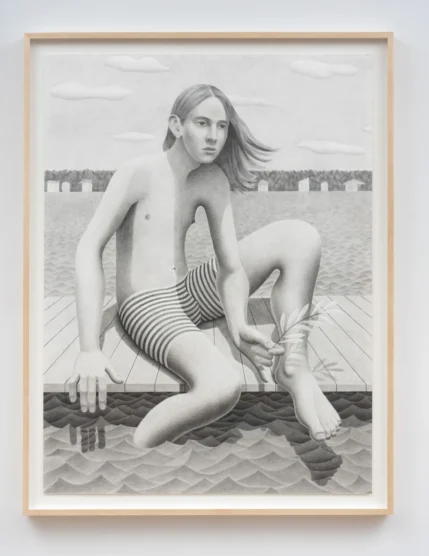

In 2022, Banx received an offer of representation from the ultrahip gallery Pangée, which has since hosted two solo exhibitions of his work and presented his drawings at art fairs in Montreal, Mexico City, and New York. Banx has also participated in solo and group exhibitions in Toronto, Peterborough, Martha’s Vineyard, Leipzig, and Berlin, and attended residencies at the Banff Centre and France’s La Napoule Art Foundation, among others. In his most recent solo, Gaze and Gesture, the world Banx’s boys inhabit is soft, smooth, and still. Solo or in pairs, his characters have succumbed to small-town summer ennui, passing their days by taking a boat ride to nowhere, dangling a leg off a dock, dissolving into an armchair, or bouncing once on a trampoline before giving up, lying down, and just staring at the clouds. “I’m often depicting these adolescent boys who are at that stage before they become adults,” Banx says.

___

“It’s right before they have to live up to expectations of the construct of masculinity. So they’re still kind of flexible and pliable and limber. Their knees are bendy, and their hands and their feet are too big, like a puppy.”

He draws mostly from his imagination, not from life or photographs, although the boys’ slouched shoulders and guarded stances were inspired by animals’ postures. “I’m really interested in how we express ourselves with the body. When you carry emotional weight, and how that shows in your body language, influences a lot of the shapes and figures.”

While Banx’s characters and scenes are fictitious, the sense of ominous foreboding that permeates the atmosphere of his drawings does have real-world origins. “A lot of the pictures I’m drawing may look like me, but they’re also—I think about my father a lot,” he says. Last year, his father was diagnosed with Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome, a medical condition affecting the brain and memory that develops most often in people with alcohol use disorder. “I always grew up around that emotional unavailability that he had, and he’s been haunted by something his whole life, clearly. The way he was medicating was to use alcohol, and it ultimately caused his demise. So that’s another big thing around this,” Banx says. By “this,” he means his impulse to draw, over and over again, adolescents embalmed in awkward innocence as they teeter on the brink of adulthood and its attendant burdens and pressures.

Some of Banx’s figures are loosely based on his dad’s friends: those who surrounded him when he was standing at that threshold of growing up, those who led or accompanied him down the path that led to his current circumstances, those who left him behind. “I used to look at home movies a lot,” Banx says. “Watching them as an adult, and knowing what has happened now, I remembered how I felt in a lot of those situations—noticing things as a kid that aren’t right, but not knowing at the time, as that’s your only understanding of a family. And then as you get older, you start to understand, ‘Oh, that’s not objective reality.’ There are other versions that could have existed.”

If Banx uses his art practice as a form of therapy, perhaps his drawings are a way of healing his inner child by giving material shape to other realms of possibility.

___

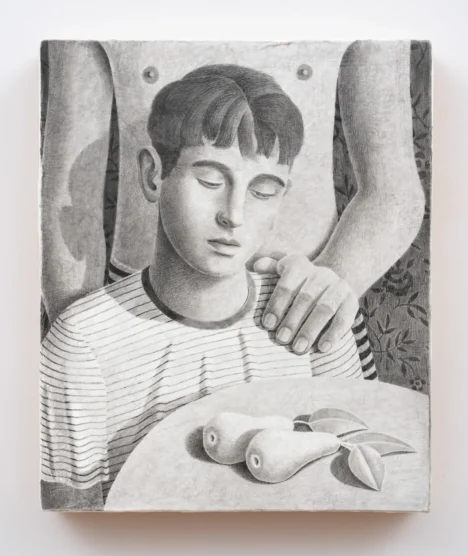

“My work is about going into my own emotions and trying to be vulnerable and exposing it a bit to talk about it,” he says. Of the figures in his work, he explains, “I want to depict them as feeling like they’re going through an epiphany, or like they’re acting with their emotions and connecting with their sensitivity and their dreams. It’s like they’re detached from their outer experience and connecting with internal life. I desire that.”

Like therapy, Banx’s process is prolonged and strenuous. He recalls one work, The Butterfly Garden, 2024, taking about seven months to complete. “My drawings are really based in devotion and dedication and taking time to sit with memories to try and understand how those have shaped who I am now,” he says. There are some that he’s still reticent to open up about, however, such as Basement, 2022, which shows a boy lying on the floor mesmerized by his own hands, perhaps aided by the ingestion of psychedelics. “I was facing very difficult memories head on,” Banx says of that scene. “I wanted to sit with that memory and see how it made me feel in my body. The drawings are very laborious, so I’m sitting there thinking about these for a long time. They are about something specific, but yeah.”

One thing Banx’s drawings are specifically not about is queer sexuality, but it’s a reading people often have when viewing his work. “We’re all so indoctrinated by the construct that any sort of intimacy between men is then perceived as sexual,” he says. While he doesn’t identify as a queer artist, Banx does “welcome ‘romantic’ in the form of a philosophy on the world or a feeling about life and what it can give you.” He likens people’s instinct to sexualize his drawings to how many choose to interpret the depictions of young girls in the work of French painter Balthus (who happens to be one of his favourite artists).

Banx draws with graphite either on paper or surfaces prepared with rabbit-skin glue and gesso (“Caravaggio style,” he says). He sometimes carves into the gessoed surfaces with a scalpel to give the composition texture and depth. “I love that drawing doesn’t really carry the weight that painting does,” he says. “My work is about this preparatory stage in life, and it’s like the drawings themselves are a preparatory thing. I kind of love that resonance. And if something doesn’t really line up right, or something logically doesn’t work, I can just say to myself, ‘Ah, it’s just a drawing. Who cares?’ ”

As blasé as that sounds, Banx cares deeply about his artwork. For him, art is one possible escape route from what’s been termed the crisis of masculinity. “These men in my life growing up, who had all these emotional issues that they didn’t really know how to talk about, it’s like, art is the way to do that,” he says. “Art is for you to express yourself in that way and feel comfortable.”

Among his most formative influences, Banx counts American author bell hooks, whose 2004 book The Will to Change resonated with him because it promotes the idea of “approaching a problem with empathy instead of hatred,” he says. Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke “changed my life,” Banx says, and his poetry inspired the title of Gaze and Gesture. “There’s just such beauty in love that he writes about,” Banx says of Rilke. “That’s what my father was missing in his life. He just needed that. That’s what these men need.

Artwork Photos by Paul Litherland.