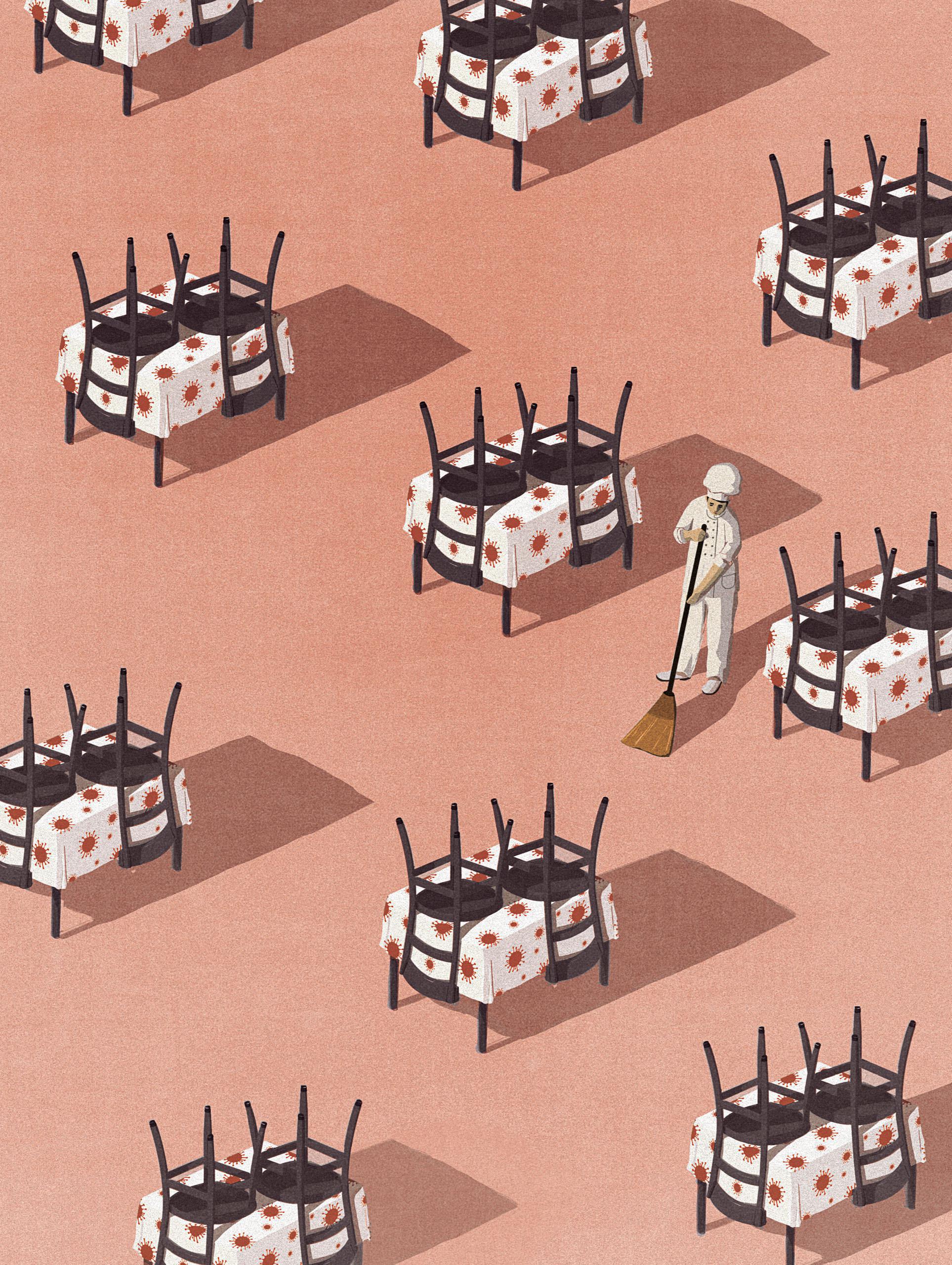

How Canada’s Restaurants Have Struggled to Adapt to COVID Restrictions

Restaurants in crisis from coast to coast.

The past year in quarantine has greatly affected small businesses, with the hospitality industry feeling the COVID crush more than most. Restaurants the world over have been adapting to a new reality, including reduced-capacity seating, plexiglass partitions, disinfection protocols, and masked service staff. In Canada, restaurateurs from coast to coast have been coping, reinventing, milking their creative juices, and mostly, struggling.

Graziella Battista, chef and co-owner of one of Montreal’s top Italian restaurants, Graziella, has been experiencing endless waves of emotions. “I’ve adopted a new attitude,” the chef says from her restaurant kitchen in Old Montreal. “There’s anger, but that anger doesn’t do any good because the situation is out of our control. So instead, I try to stay calm, but it’s a lot of work.”

Battista has had plenty to be emotional about. On March 15, 2020, the Quebec government ordered all restaurants to operate at half capacity. By mid-June, dining rooms reopened, and, benefiting from the summer weather, terrasse dining became a popular way to operate. But by October 1, all on-site dining was shut again, and at the time of writing, there is no news as to when Quebec dining rooms will reopen. The winter months have been grim. “The closures have been the toughest,” Battista says. “When we opened in summer, we were busy and I felt people wanted to get out. But then, with little notice, they closed us down again. My fridges were full of food, including four lambs, three calves. For the first time, we’ve been stretching out payments to our suppliers, 60 days, sometimes 90. And I have never waited more than 15 days to pay a bill.”

Despite the shutdowns, Battista has kept the business solvent thanks to takeout. “We’re not making a profit, we’re not even breaking even,” she says, “but we’re busy and have a lot of orders. The support from our clients has been remarkable. But the fatigue isn’t physical, it’s mental. It’s also a very lonely time. We go from the restaurant to home, home to the restaurant.”

On the West Coast, shutdowns have not been as frequent as in Quebec, yet the restaurant industry is equally imperilled. “Chefs don’t open up restaurants to be empty,” restaurateur and chef Vikram Vij tells me in a phone interview from Vancouver. “We open to be full. For 30 years I’ve been taking menus to customers’ tables, having conversations with them. That was our high, seeing people, conversing. Now, with their masks on, I can’t even tell if they’re enjoying their food.”

Vij closed his restaurants—Vij’s, My Shanti, and Rangoli—when the pandemic started, with only takeout and delivery menus available. Of his three establishments, he calculated that he could only manage two rents and thus closed Rangoli. By summer, on-site dining was back on at Vij’s and My Shanti, yet at half capacity. And though Vij’s was famous for its hours-long lineups, tourists made up 70 per cent of its customer base. “With a 120-seat restaurant, you can distance the tables. But our overhead, rent, and staffing cost the same,” Vij says. “Right now, cheap takeout is what’s working. Specialty restaurants that spend on decor, plates, and a fancy napkin rely on high alcohol sales to make a profit. That’s why we’re hurting. We’ve always done takeout, but few want a bottle of wine to go with it.”

Across the country in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Jeremy Bonia has been dealing with many of the same challenges. Bonia is the sommelier and co-owner at St. John’s top gastronomic table, Raymonds, which has felt the loss of the tourist trade even more sharply. “What we did was scale back and drop prices to become more COVID-friendly and more local-friendly,” Bonia says. As an estimated 98 per cent of Raymonds’ customers are tourists, that transition was significant. “Our menu is hyperlocal,” he notes, “so it’s not like Newfoundlanders are that interested in eating food they already have at home.”

The outcome of these pandemic challenges is sure to transform the industry as a whole. Bonia sees no business coming out on the other side the same size as before. “There’s nothing like a pandemic to force you to reevaluate your business,” he says. “We may not have the crippling rents restaurants face in cities like Toronto and Vancouver, but we still had to cut the number of our staff by half.” Yet despite the cuts, Raymonds pulled off the best November financially because, Bonia believes, people were at home and not vacationing so they had money to spare. “It was nice to see locals come out, support us, and value what we’re doing.”

Battista concurs: “We’ve connected with the neighbourhood and gathered with the other merchants on the street to work together. I’ve also learned a lot from this style of selling food. I feel takeout and online shopping will remain because, as I’ve also discovered, a lot of people don’t cook. We are doing everything to get back. It’s a bad moment, some will fall, but I’m going to fight all the way to make sure I reopen my dining room.”

Vij also sees a silver lining in all the hardship. “People will come back and support us. Humans want to support each other. And the government will too. But this pandemic is a global phenomenon, and I feel the pain for the cooks all over the world. I can only commend the locals for supporting us so far. And the government, because if they hadn’t helped, the industry would be dead.”

Yet despite the glimmer of optimism, there is obviously still some way to go. Vij says, “You can say everything is fine, but that would be like putting ointment on a burn.”