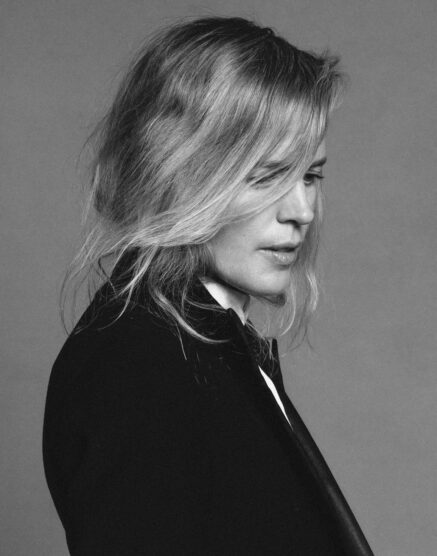

Claudia Dey Is Powerful With Her Prose

The author on writing as necessity, deconstructing archetypes, and her latest novel, Daughter.

Novelist Claudia Dey is many things: a Governor General’s Award-nominated playwright, an accomplished essayist, a clothing designer, an occasional actress—and a proud Scorpio. “My desire for dark and empty spaces, being alone in my mind or in my study, is very kind of Scorpionic,” she muses, when asked which qualities of her sign she embodies most. “That need for isolation, but then matched by a need for contact, like a contact high, from friends and intimates. What else? I guess, sensuality in all things.” Dey speaks to me from her home in Toronto, where she lives with her husband and their two sons. I’ve caught the author in a moment of that much coveted isolation. Her house is empty; she’s lounging on a red-velvet couch.

Dey’s Scorpionic nature, her affinity for secrecy, independence, and sensuality, will hardly surprise readers of her latest novel, Daughter. Praised by Sheila Heti, Miriam Toews, and even singer-songwriter Feist, Daughter chronicles the propulsive power struggle between two writers, father and daughter Paul and Mona Dean. Charismatic and celebrated, Paul runs between his three daughters, his ex-wife, his current wife, and his younger lovers with careless entitlement. When Mona becomes an accomplice in one of her father’s numerous affairs, she finds her proximity to it intoxicating. (Dey describes Mona and Paul’s relationship as containing elements of a “bad romance.”) But when the affair is revealed, and her family is fractured, Mona must find agency outside the gravitational pull of her famous father’s orbit.

“Writing was just always a necessity for me,” Dey, who wrote and performed her first play at 12, reflects. “The only part I remember is a scene where I poisoned myself after a failed love affair and do this kind of death dance on stage before dying.” Dey studied English literature at McGill University and then playwriting at the National Theatre School of Canada. For years she was the playwright in residence for Toronto’s Factory Theatre, but her mentors saw the spark of a fiction writer in her work.

Dey was always drawn to books: “It’s the most persuasive form, I think, and the most intimate.” Stunt, her debut, was published in 2008. Lyrically written, it follows a synesthetic nine-year-old girl in Toronto after the disappearance of her father. Her second novel, Heartbreaker, a complex family drama set against a dystopian cult, was published a decade later. When she returned to prose, her writing was informed by a profound loss. “After my stillbirth, I did not write fiction for nearly 10 years,” Dey wrote in her Vogue essay “There Is No Script When You Experience a Stillbirth.” Her novels demonstrate a deep sensitivity to themes of grief and motherhood. But while Heartbreaker explored these topics against a heightened, and in many ways fantastical, backdrop, Daughter revisits questions of family, loss, and maternity in a more direct and everyday setting.

This turn to realism may have also come from the conditions under which the book was written. She wrote Daughter during the pandemic, in “a pressurized state,” Dey explains. Unlike her previous books, Dey wanted Daughter to eschew fantastical worldbuilding for immediate realities.

___

In addition to the enforced isolation, she wrote with a list of self-imposed rules: “Write pressed sentences. Write only places I’ve visited. No mythologizing characters. Something about only plain names. And you can that see I’ve mostly adhered to those constraints.”

The constraints helped Dey transmute that pressurized quality into the novel, suffusing it with a gripping emotional urgency. Dey prioritized sentences with velocity. “I was really tired of beauty,” she confides. “Of course, I still as a writer would strive for a beautiful sentence,” but she admits that beauty is “certainly never the most interesting thing to me.” She was also less concerned with forcing the novel to fit into conventional literary structures, focusing instead on the mood of each scene and capturing the emotional core of the Deans’ fractious relationships.

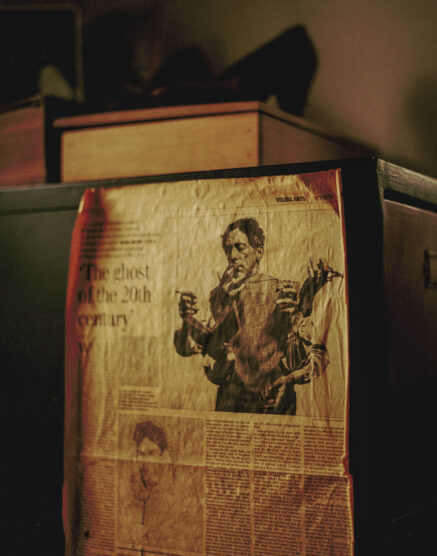

Dey modelled Mona’s celebrity father after the literary crushes of her youth—“the Leonard Cohens and the Henry Millers”—with a dash of Bill Murray. She was also inspired by famously fraught families: the Hemingways and the Kennedys in particular. “These families that structure themselves around a powerful patriarch, even though so often the motor of the enterprise is the women, who typically are also far more interesting,” Dey says. In the novel, Mona’s work explicitly grapples with the archetypes of father and daughter; she writes and performs a play about Ernest Hemingway’s granddaughter, troubled supermodel Margaux Hemingway. Later, she attempts a sequel from the perspective of Margaux’s sister, acclaimed actress Mariel Hemingway. Dey shares her protagonist’s fascination: “I definitely am so interested in building a matriarchal canon and reading that way,” she says, adding, “Just in terms of archetypes, like finding the shadow side or the underside or the underworld of that archetype.”

And indeed, for all of Paul’s charm, it is Daughter’s complicated female ensemble who enchant. When one enters the scene, the gravity of the novel shifts. As the perspective moves between Mona’s first-person accounts and third-person vignettes of her extended family, it is the solidarities and animosities between these women, their evaluations and reevaluations of their relationships with each other, that propel this intimate drama forward. Daughter showcases Dey’s talent at conveying deeply human emotions, petty or profound, as well as her gift for subversion.

Take Dey’s treatment of absences. They are integral to the novel, but rather than acting wholly as roadblocks or instances of loss, Dey probes what absences offer us. Paul’s longstanding absence from Mona’s life is key to his power over her; it creates the space for yearning. In a complementary observation, Dey writes of Paul’s rib—specifically the missing portion, which had been removed to repair a boxing wound (like Ernest Hemingway, Paul is an avid bruiser). Fans, especially young women, would crowd around him to see his scars. “Paul would list the things that fit most nicely in his cavity: a tongue, a small breast, a cigar, a set of keys, a baby’s foot, a champagne flute, the muzzle of a shotgun. When he pressed the muzzle of his shotgun into his cavity, Paul would say to the swell of women, he could get the muzzle right against the lower chambers of his heart.” Dey draws out the absence’s underside. Instead of symbolizing a pure deficit, Paul’s injury becomes a method of distinction and seduction, an invitation for connection.

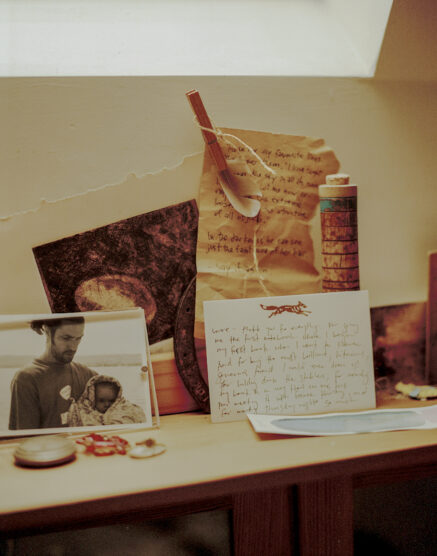

Daughter is bursting with paragraphs like these, full of surprising sentences and subversive images. It is, perhaps, inevitable for an author so attuned to both the sensory and the sensual, on and off the page. For the launch of Daughter, Dey approached Courtney Rafuse, the perfumer behind Universal Flowering, to craft a fragrance inspired by the novel. Universal Flowering’s perfumes had been both “sustaining” and inspiring during the writing process. Dey wore them often while working on Daughter, submerging herself in their evocative scents.

Mona, the fragrance, is as smoky and seductive as its namesake, distilled into notes of warm stone, burnt sugar, vetiver, and amber. “I thought this entire book is about getting to the most precise expression. What encapsulates that more than a perfume?” Dey says. Creating a fragrance is a complex but delicate alchemy. Perfumers carefully balance the ratios of oils and resins, and aromatic chemicals to create a scent that evokes a specific mood or feeling. Like literary characters, any one ingredient can easily overpower the whole. “It did feel like sort of a perfect metaphor for how the book was written. It has its elements, its characters in combination with each other. A real atmosphere.”

Still, for all her artistry, Dey doesn’t take anything, least of all herself, too seriously. “Listen,” she laughs, “the next thing I write may be the most conventionally structured. I tend to go for the antidote to things I’ve done previously, but who knows!” Dey has many more archetypes to explore—and refuses to affix herself to just one.