Foundation of Change

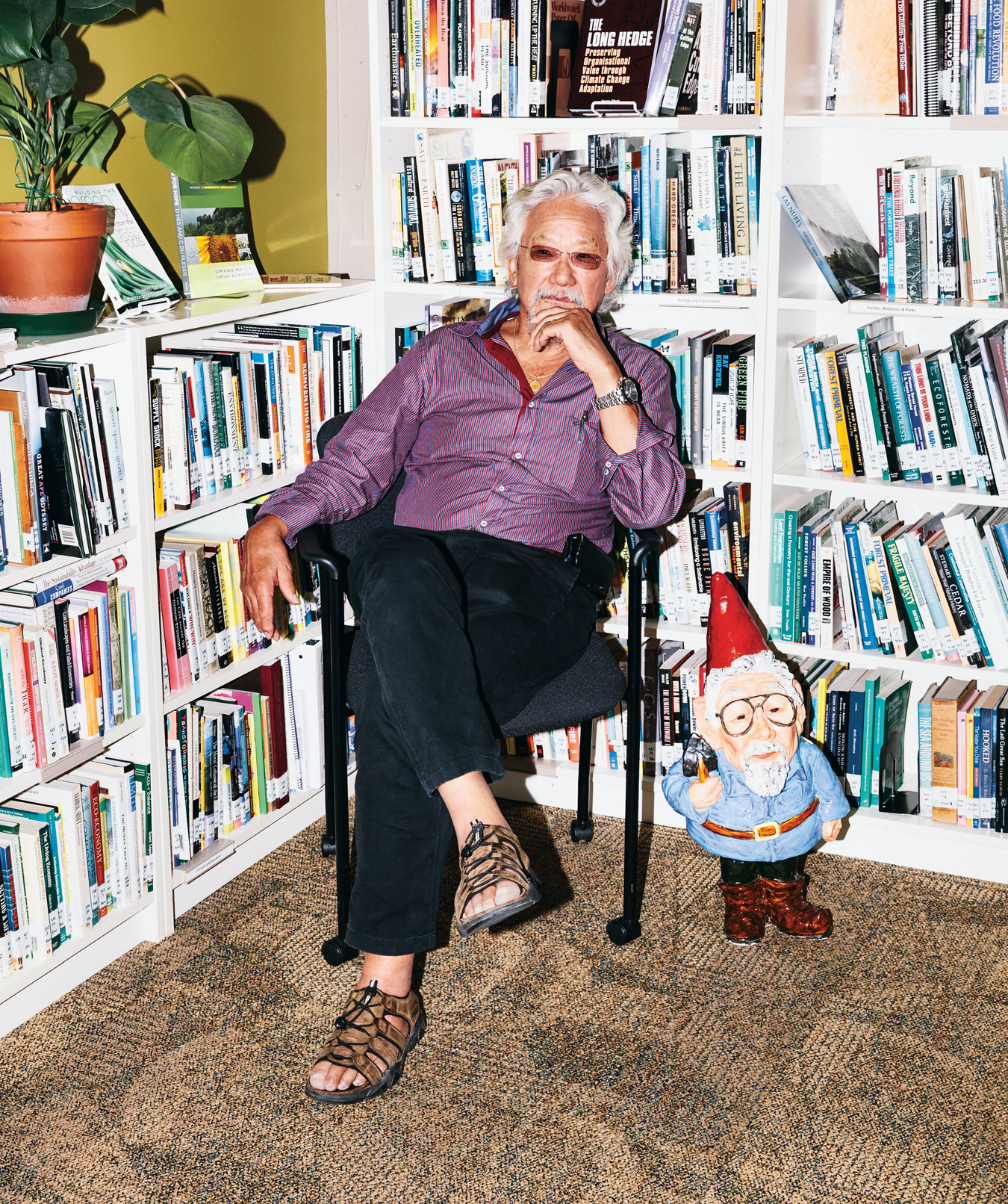

David Suzuki looks back on a life of increasing activism and improbable fame.

One morning in July 2013, David Suzuki’s wife, Tara Cullis, was swimming in the ocean in front of their Point Grey home in Vancouver. Suddenly, she couldn’t breathe. She barely made it to shallow water, gasping, before she collapsed.

“I was on the porch, and someone came for me,” Suzuki recalled recently, in his office at the David Suzuki Foundation, not far from their home. “By the time I got to her, an ambulance was on the way. They rushed her into an operating room. Her heart was functioning at 20 per cent, unable to pump blood through her body. Her lungs filled with fluid. She was in intensive care for five days and almost didn’t pull through. She’s 13 years younger than I am, and we always assumed I’d go first.”

Next spring, Suzuki turns 80. Arthritis has skewed his fingers, but otherwise he remains remarkably youthful, lithe, and fit, with smooth skin, a crop of white hair, and his trademark goatee. His wife’s near-miss is not his only memento mori. A younger sister died a decade ago. Alzheimer’s has taken members of his mother’s family. Many of his close friends—people like Jim Murray, long-time producer of his CBC television show, The Nature of Things, and Jim Fulton, the former NDP Member of Parliament and executive director of the foundation—have passed. Little wonder he calls this stage of his life “the death zone”.

“I never used to read the obituaries,” he says cheerfully. “Now I do. But getting old is actually quite liberating. I can say exactly what I think. I don’t have to worry about getting a raise or a promotion. I appreciate the blossoms, and I used to be so driven that I never paid attention to those things. It was always, ‘I’ve gotta finish this project.’ ”

Not that he has slowed down all that noticeably. When we met, he was about to embark on a 12-city tour with a punishing slate of speeches, readings, and media spots to promote Letters to My Grandchildren, which was published by Greystone Books in May 2015. It is the fifty-fifth book that bears Suzuki’s name. He’d just spent four weeks in French immersion in Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice, because he was self-conscious about his poor French when he visited the foundation’s Montreal office. The requests for endorsements, blurbs, speeches, and appearances keep rolling in—“dozens every week,” says his executive assistant, Deanna Bayne. He tries to lead a normal life—he has no handlers, takes the bus, waits in line at the movies—but often gets ambushed by strangers who want a minute of his time, a selfie, or a hug. Patiently translating scientific findings into popular language has made David Suzuki a celebrity, though he often finds the price of fame onerous.

As a pioneering environmentalist, he ranks up there with Edward Abbey, Wendell Berry, and Rachel Carson (whose 1962 book, Silent Spring, helped waken him to environmental issues). Today’s proponents of sustainability stand on his shoulders. Mark Jaccard, the Simon Fraser University economist who was part of a Nobel Prize–winning team, and who basically invented the notion of the carbon footprint—a way of measuring one’s impact on the planet—calls Suzuki “an inspiration” who helped set him on his path. For half a century Suzuki has been a cautioning voice about our stewardship of the planet. A typical warning: “Our leaders simply do not understand the gravity nor the immediacy of the environmental crisis. Every election from now on must drive that home to political candidates.”

Suzuki said that 25 years ago. Today, most scientists agree that climate change, with its dire implications, is the most urgent challenge facing humankind. Global-warming deniers have taken on the taint of 9/11 conspiracy theorists. Yet, Suzuki admits, we’ve made surprisingly little progress in persuading the public, and the politicians, that the path we’re on ends in disaster in a very few generations. The growth of carbon dioxide emissions, mainly from fossil fuel, remains a threat. Carbon in the atmosphere keeps accumulating. In 2014 the average global temperature was the highest ever recorded.

Some elders grow content and accepting, finding sweetness in the every day. Others become bitter: bad memories turn rancid, and even good ones are darkened by the melancholy of things irretrievably lost. Suzuki seems to vacillate between those poles. Having children is surely the great act of optimism. If he were approaching his 30th birthday, rather than his 80th, would he bring kids into today’s world?

“Knowing what I know now, I wouldn’t,” he says. “Overpopulation is one of the problems. I said to my daughters, ‘You know where this is going—why are you having kids?’ They both said that not having children would be giving up. Children guaranteed their investment in the future.” The ultimate paradox: commit to making the world better by making it ever-so-slightly worse.

Still, he sees cause for optimism. “There are plenty of young people doing good things, lots of small groups focusing on local issues. The Internet has opened new possibilities for change.” He mentions Naomi Klein, Craig Kielburger, and Brigette DePape, the page who held up a “Stop Harper” sign during the Throne Speech in the Senate and was promptly fired. “We’ve never seen anything like what Harper has done in the last 10 years,” says Suzuki. “He’s committed a crime against future generations.”

If such candour is part of the liberation of old age, it makes things tricky for the foundation that bears his name and attracts some $8-million a year. “That’s why I resigned from the board,” he says. “I’ve cut formal ties, though I still help raise money. Every time I say something critical of the government, the foundation gets audited by the CRA. We’re being audited right now—for the second time. It’s expensive, and it’s psychologically difficult. A dark cloud hangs over the whole office while it’s going on.”

Suzuki’s activism came about slowly, almost by accident. At high school in London, Ontario, in 1954, he got a scholarship—“worth more than my father earned in a year”—to Amherst College in Massachusetts. Though his parents hoped he’d be a doctor, in pre-med he discovered “the elegance and precision” of genetics. After doing his PhD at the University of Chicago, he took a job as a research associate at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the components of uranium had been isolated before the Second World War. One of his grandfathers had been a samurai; all of his grandparents were Japanese; the irony of working in a place that helped develop the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not lost on him.

“Getting old is actually quite liberating. I can say exactly what I think. I don’t have to worry about getting a raise or a promotion.”

Nor was the fact that Oak Ridge was racially segregated: churches, restaurants, laundromats. His best friend in the lab was a black woman. Having felt the sting of racism himself—he was interned with his family in the B.C. Interior during the war, but shunned by the Japanese because he spoke only English—Suzuki at the time identified with “the blacks, not the whites. I became angrier and angrier. I’d see WHITES ONLY signs and literally throw up. My [former] wife, Joane, said, ‘We need to leave here. This is making you sick.’ ”

He took a job teaching genetics at the University of Alberta, which had a community-channel program called Your University Speaks. A natural from the get-go—relaxed, confident, and with a resonant voice—Suzuki was asked to appear many times. “People began stopping me and saying, ‘That was a great show.’ That’s when I realized what a powerful tool television is.”

The frigid Edmonton winter prompted a move in 1963 to the University of British Columbia. Soon Suzuki was doing guest spots on CBC Television. One thing led to another, and before long Suzuki on Science was born, a show hosted by a hip, young geneticist of Asian descent with a gift for demystifying science. Divorced from Joane and yet to meet Tara, he revelled in the life of the cool, long-haired bachelor prof, adored by his students—who called him Dave—if not by more conservative faculty.

Suzuki went on to host a TV show called Science Magazine, and he helped create the hugely popular Quirks and Quarks on CBC Radio. In 1979, the CBC merged his TV show with The Nature of Things, which had been on air since 1960. “The people behind that show—John Livingston, Lister Sinclair, Jim Murray—were passionate about birds and nature. I realized later that Jim had been grooming me. They needed someone to be a champion of the environment, the way Pierre Berton had become a champion of Canadian history.”

Viewers who’ve followed the show over the decades have watched Suzuki gradually morph into a global beacon for environmental activism. “I always thought of myself as a messenger,” he says. “To become so closely identified with the message has been a mixed blessing. The other day I was hurrying home to babysit my grandson when someone on the street said, ‘Do you have a minute?’ ‘Actually,’ I said, ‘I don’t.’ He got really angry: ‘I took one of your courses, you asshole!’ ”

A decade ago, when CBC produced The Greatest Canadian—a combination TV series, history lesson, and popularity contest—Suzuki placed fifth, ahead of such luminaries as Lester B. Pearson, Alexander Graham Bell, and Sir John A. Macdonald. More recently, in 2011, Reader’s Digest called him the “most trusted Canadian.” A couple of years later, in an Angus Reid poll, he was voted this country’s most admired citizen.

Still, he’s not “Saint Suzuki” (as one critic called him) to everyone. If Peter Mansbridge, Rex Murphy, and Amanda Lang got censured by the CBC for using their positions for personal gain, and Evan Solomon got sacked, what about Suzuki? Hasn’t he parlayed CBC-based fame into $30,000 speaking gigs? (He himself—not the foundation—pays his assistant and his office expenses, and for every paid speech, he gives six or eight unpaid ones.)

Right-wingers are not his only critics. Some young activists are ambivalent. “Yes, of course, he’s done good things in terms of awareness,” says someone who works in clean energy and spoke frankly so long as he went unnamed. “But as long as we see things like climate change as an environmental issue, not an economic and political one, it falls off the list of voter priorities, which lets the politicians kick it down the road. My work involves not talking about the environment as such, but about public policy and economic development. That’s the discussion we need now. I’m not sure Suzuki gets that.”

Perhaps so, although Suzuki’s “Blue Dot” campaign, launched in 2014, suggests otherwise. It seeks to amend the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to include a healthy environment as a fundamental human right. Suzuki calls it “my last big push,” though Deanna Bayne says: “I don’t think he’ll ever stop. His work isn’t just his work—it’s his life.” Indeed, he soldiers on with the energy of one half his age. Last year he attended the Kinder Morgan protest at Burnaby Mountain to denounce government support of fossil fuel, calling opposition to the pipeline “a clash between two world views.”

When I met him for lunch in July 2015, after his book tour, Suzuki recounted his attempt to persuade Justin Trudeau to strike a deal with the NDP, in a few key ridings, to defeat Harper in the October election. The next day he was off to Toronto, to join the likes of Jane Fonda, Bill McKibben, and Naomi Klein in the March for Jobs, Justice, and the Climate, and then on to Fort St. John, B.C., to protest the Christy Clark Liberal government’s approval of the Site C dam.

“You know the First Nations story of the hummingbird flying through the forest?” says Suzuki, finishing his cappuccino and, in his usual shorts and sandals, heading back to his office. “The forest is on fire, and the hummingbird keeps getting a drop of water from the pond to put on the flames. The other animals ask him, ‘What are you doing? You’re crazy. That’s not going to stop the fire.’

“The hummingbird says, ‘I’m doing all that I can.’”

This story was originally published in Autumn 2015.