A Surreal Day in the Neighbourhood

Do you remember the first time you were traumatized by a cartoon? For me, it was when the evil queen in Disney’s 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs mutated into a gnarled old hag. I found most witches terrifying back then, but now, as an adult, I see them as more than a little misunderstood. Under patriarchy, the natural processes of aging and infertility render older women powerless and invisible. Sure, some of those subjugated witches took their acts of revenge too far, but who wouldn’t feel consumed by righteous anger?

“I was so absolutely into the villains,” says Venezuelan American artist Alex Da Corte, whose exhibition Ear Worm is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto until August 3, in an interview with Apollo. Now based in Philadelphia, as a Catholic schoolboy in New Jersey, the self-proclaimed homebody turned his bedroom into a devotional shrine to all the baddies from Disney movies, painting Cruella De Vil, Scar, Jafar, and other camp misfits directly onto his walls. “It was my version of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel,” he told Interview.

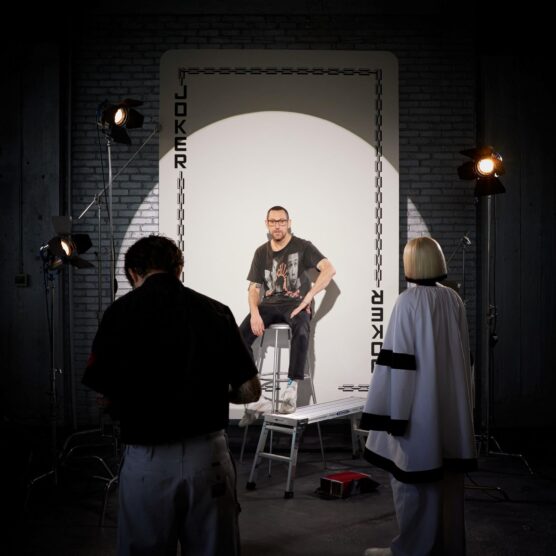

Photo by Natalie Piserchio, courtesy of Alex Da Corte studio.

Now, Da Corte has transformed the second floor of MOCA into a dreamlike space populated by icons of Americana, with plush yellow carpeting underfoot, soft pink and golden light wrapping the space like a weighted blanket, and hypnotic video and audio playing on a slow, never-ending loop.

The work Rubber Pencil Devil, 2018, is a 57-part series of vignettes originally commissioned for the 57th edition of the Carnegie International exhibition in Pittsburgh (it was also part of the official exhibition at the 2019 Venice Biennale). Altogether, the short films span two hours and 40 minutes, and they feature Da Corte and others performing in costume as characters and objects such as Mr. Rogers, Lowly Worm, the Pink Panther, Sylvester the Cat, Oscar the Grouch, Satan, the Statue of Liberty, a bottle of Heinz ketchup, a cigarette, and more. The films are rear-projected onto four giant building blocks painted purple, red, orange, and red again, and a stepped pedestal, curved like a spool of unwound film, serves as seating for visitors to the immersive Gesamtkunstwerk.

“How do I know my life?” Da Corte says in a video made about Rubber Pencil Devil for Art21. “How do I know my politics? How do I know my religion? How do I know my love? I probably learned it from my family, but mostly, I probably learned it from TV.” The artist makes sense of his own identity, and U.S. culture as a whole, through inhabiting and unsettling its national idols and archetypes. With their contexts subverted, these symbols, and the moral codes implicit in their depictions, are opened up for reappraisal.

Adjacent to Rubber Pencil Devil at MOCA is Mouse Museum (Van Gogh Ear), 2022, a cabinet of curiosities shaped like Mickey Mouse’s left ear (a reference to Claes Oldenburg’s Mouse Museum, 1965–77, but spliced in half in homage to the appendage lopped off by Vincent van Gogh). As in Oldenburg’s work, Da Corte displays assorted knick-knacks and studio-made objects he owns, many of them props from Rubber Pencil Devil.

In a video by the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark about the making of the artwork, Da Corte reasons that the “pieces of plastic that you collect” as a child, such as Happy Meal toys or hair clips, become the “stones you leave in the forest as you walk through your life” or the way you mark important occasions and construct narratives about yourself and your place in the world. “These are objects that of course hold meaning to others, but they hold specific meaning to me,” Da Corte says of what he chose to include in his Mouse Museum. “I want to put them in this place because I want to let them go, to maintain that my life is still moving forward, and that these kind of energies that the objects possess stay with me, but their physicality can go. As is with life.”