How Zadie Xa Is Reimagining Identity and Folklore in Contemporary Art

The Korean Canadian artist blends ancestral narratives with experimental media, creating arresting installations that challenge how we see culture and self.

In a cavernous East London studio filled to the gills with treasures, Zadie Xa is preparing for what might be the most significant exhibition of her career to date. Earlier this year, the Vancouver-born artist was selected as one of four nominees for the prestigious Turner Prize, which awards one artist from or primarily working in Britain £25,000—as well as lifelong bragging rights. Named for the radical 19th-century painter J.M.W. Turner, it’s a very British prize (past winners include Damien Hirst, Anish Kapoor, and Steve McQueen), and Xa feels honoured by the acknowledgement but a little uneasy, too.

Xa, who is Korean Canadian, has lived in London for over a decade. She moved to the capital city in 2012 to attend the Royal College of Art. Before that, she studied at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver and lived in Florence and Madrid with her husband and frequent collaborator, artist Benito Mayor Vallejo. She thinks a lot about belonging, with the facets of her identity bound up in entangled feelings of attachment and estrangement. Although she grew up in Vancouver, she had never been formally invited to show in her hometown until recently. And while she feels embraced by the art scene in London, where she is represented by gallery Thaddaeus Ropac, she senses the shadow of far-right nationalism growing across Great Britain since Brexit and COVID-19. As a non-white immigrant, it’s not the friendliest atmosphere to plan her future.

But as her art can attest to, Xa has never been one to shy away from sitting in discomfort or confronting anxiety. Moving fluently across artistic disciplines—including performance, painting, sculpture, textile, and installation—she creates immersive environments thick with saturated colour and sensory overload. Woven into the exuberance, however, is a thread of tension: ecological grief, diasporic dislocation, and the dual role art plays as both a mode of care and a form of complicity. The willingness to hold contradiction is what makes Xa’s practice resonate so widely, and why her most recent institutional accolade feels both affirming and fraught.

The Turner jury nominates artists for an outstanding exhibition or other presentation of their work. Xa is skeptical of this off the bat: “There’s no such thing as the ‘best’ shows,” she insists. “Everything is very organized and curated and gatekept. These things are so subjective.” She was nominated for Moonlit Confessions Across Deep Sea Echoes: Your Ancestors Are Whales, and Earth Remembers Everything, which she showed at the Sharjah Biennial 16 in the United Arab Emirates—another politically fraught country but about as far away as you can get from Bradford, West Yorkshire, where her work is being presented in advance of the prizewinner announcement on December 9. Her exhibition combines vivid large-format paintings of fantastical landscapes with sculpture and sound works.

“The space that I got in Bradford is almost two times bigger than Sharjah,” Xa says. There is clearly some reconfiguring that must be done, as it’s not only a larger space for her to fit her multisensory installation into but also longer and narrower. She sees this as an opportunity for transformation. First, she’s installing gleaming silver floors underfoot to reflect the sunset colours of the painted wall murals and create an otherworldly glow in the room.

Zadie Xa’s works invite viewers into immersive worlds of imagination and reflection. Ghost is a monumental chandelier made up of 652 tiny brass bells suspended in the shape of a turban conch shell.

Photos by Danko Stjepanovic, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery.

Second, she’ll add another shell sculpture to the three she brought to Sharjah. Each of these hangs from the ceiling and has a sound component that relates to the title of the exhibition. When visitors hold the shells to their ears, like telephones, they’ll hear whispered confessions, the music of salpuri, a Korean exorcism dance, mournful whale song, and the staccato clicks of Morse code.

Third, Xa will add a plinth beneath the show’s central sculptural element, Ghost: a monumental chandelier made up of 652 tiny brass bells suspended in the shape of a turban conch shell. For the sculpture to maintain its geometry, each bell must remain calibrated to an exact coordinate—hence the addition of the plinth. “It’s basically a barrier for people,” she explains. “Bells are meant to be shaken,” she says. “There’s this tactile desire to touch, right?”

In Korean shamanism, however, which Xa often references in her work, the ringing of bells is employed with ritualistic significance to invoke the supernatural or exorcize evil spirits. Hanging silently out of reach, Xa’s bells tremble with the tension of latent possibility. “This is almost like use in case of emergency, when you break something in order to grab the axe that you need,” she says of the look-but-don’t-touch sculpture. “You need to damage it in order for it to fulfil its function.”

___

Moving fluently across artistic disciplines—including painting, sculpture, textile, and installation—Zadie Xa creates immersive environments thick with saturated colour and sensory overload.

Another recurring theme in Xa’s work is marine life: the dolphins, humpback whales, and orcas native to the Pacific Northwest. They’re “kind of the canaries in the coal mine in terms of feeling the effects of ecological destruction,” she explains of her beloved cetaceans. By depicting specific creatures in her paintings, such as Helen, a Pacific white-sided dolphin who was held in captivity in San Antonio, Texas, for decades before she died recently, or Sweet Girl, a humpback whale killed by a boat strike in French Polynesia, she ties planetary collapse to intimate, embodied stories. Her artworks become offerings and memorials for lives cut short.

“The past two and a half years now, it’s been very hard to make art,” Xa admits. Every day, she feels bombarded by imagery of violence and destruction, with social media supplying a constant stream of bite-sized videos in dazzling 4K that show people being pulled out of rubble in Gaza or majestic wildlife being mutilated by humans. By processing her grief and outrage through painting, she says, “I was really going through the motions of shock.”

Xa is candid about the contradictions of making art in a time of climate crisis and political upheaval. “Being an artist, in many ways, is quite antithetical to that,” she says, referring to ecological survival. “You’re using chemicals and materials, and you’re just creating more stuff. It ends up feeling like a narcissistic pursuit, and there’s so many things about the art industry that are problematic.”

La Danse Macabre, oil and oil bar on machine-stitched washed linen and canvas. 280 x 640 cm. Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery. All images © Zadie Xa.

Handled responsibly, however, art can serve as an effective agent of attention. It can hold grief without numbing it, and keep audiences present rather than distracted. “Maybe this is why I’ve leaned heavier into what I would call sensorial colours and images and textures in a way where, maybe before, I was leaning more on research and concept,” Xa says of how her recent work differs from her earlier output. “This time, I’ve been much more emotionally led in terms of wanting to create enveloped spaces with colour.”

To enter one of Xa’s exhibitions is to be wrapped in colour, sound, and texture but also to be unsettled. Like fish hooked by tantalizing bait, visitors are initially lured by beauty, then abruptly destabilized by the sting of grief. The tension is deliberate. Her work resists the easy consumption of crisis as spectacle, instead asking viewers to slow down and engage in more attentive looking and listening. And once viewers are immersed in her world of abundance tempered with anxiety, they are rewarded with the ability to decipher hidden messages.

Xa is fascinated with coded communication. “I’m interested in using embedded semiotics within my work,” she says. Take her patchwork paintings for example. Early in her career, she says she “hated” modernist American abstraction, associating it with elitism and exclusion. Over time, however, she came to see the visual language already embedded in undervalued practices such as Korean bojagi, which were traditionally made by women sewing together scraps to make wrapping cloths, or African American quilting patterns, which some historians believe signalled safe routes to people escaping slavery.

Both textile traditions are forms of communal labour, rooted in the everyday and beauty, dismissed historically as craft but in fact, as Xa says, “works of genius abstraction.” She notes, “I’m very attracted to folk traditions globally, primarily because it’s the cultural language of the working classes.” While her paintings trace a direct lineage to the works made by these unnamed matriarchs, Xa has since warmed to artists in the Western canon. “Now I have a real appreciation for Paul Klee, and I really love Sonia Delaunay,” she says.

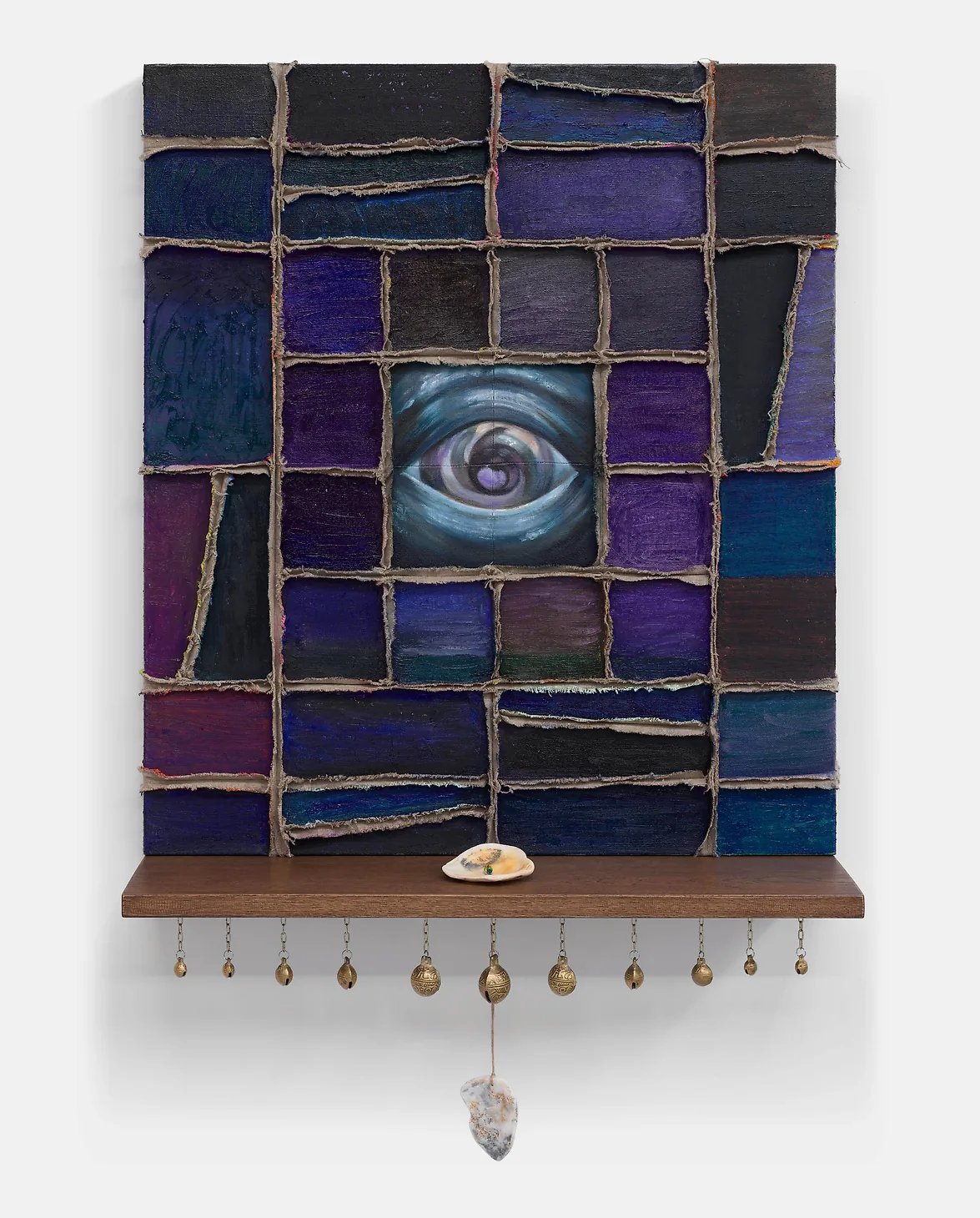

Vigil for Sweet Girl, 2024. Oak, sea shell, beads, oil and oil bar on machine-stitched washed linen. 83 x 70 x 28 cm. Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery. All images © Zadie Xa.

In Xa’s own work, symbols are layered to mean different things depending on who encounters them. Art is not about singular interpretation but rather plurality and hospitality. Viewers are encouraged to bring their own cultural memories and readings to her works. “As I get older, I’m less interested in myself and more in connecting with other people,” she says. “When there are artists who come from minority backgrounds, who otherwise are not told to celebrate where their family comes from, especially in a climate like we’re living in now, that’s the thing that really excites me.” She recalls leading a tutorial in which a student placed images of Xa’s work on a mood board alongside Nigerian ritualistic performance. “I just thought that was the whole point of it, because she could see herself through the work,” she says. “And that was most important thing for me.”

For Xa, success is not when audiences decode every reference, but when her work sparks recognition in unexpected places. “Something that most excites me is when people find a point of pride and curiosity in the culture that they come from,” she says. “You’re very much directed towards what should be interesting, and I think we often overlook things that are in our backyard.”

___

“Much of my work actually is very much rooted in what I think about on a day-to-day basis.” —Zadie Xa

Collaboration is another constant in her practice, and the people she teams up with are often from her inner circle. Since 2016, her husband has been closely involved, designing masks, sculptural elements, and most recently, the chandelier of bells. Their working relationship is less about hierarchy than it is about dialogue. Even though “it’s under the umbrella of my work,” Xa says, “he always has a really integral role.” Her refusal of the myth of the lone genius is both ethical and political. She is clear about the art world’s long history of obscuring the labour of collaborators behind the singular figure of the artist. By foregrounding Vallejo’s role, she redistributes authorship, insisting that creation is rarely solitary.

Xa’s commitment to sharing responsibility extends to her relationship with her audience. She taps into the personal to access the universal, and by telling her own story with vulnerability and authenticity, helps others discover their own meaning. In building her exhibitions, she is constructing parallel worlds that mirror our own, the way we use dreams as tools to understand our subconscious fears and desires about reality. All of her disparate references are stitched together, like bojagi, to form a new whole. Familiar figures are able to transcend their mediums and voyage between exhibitions, connecting across far-flung geographies and nonlinear time, but they experience the same whiplash as everyday people, between violence and wonder, and abundance and loss.

The blunt edges of a blade will still cut flesh (self portrait at 40), 2024. Oil and oil bar on washed and machine stitched linen 200 x 180 cm. Photo by Eva Herzog, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery. All images © Zadie Xa.

For Xa, Earth itself is the ultimate archive of these collisions. The last part of her exhibition title, Earth Remembers Everything, comes from the name of a book published in 2012 by Canadian author Adrienne Fitzpatrick. Reading it made Xa think about “the history of violence that’s embedded within the substrate of the world.” She grew up Catholic and says that religion imprinted upon her a punishing fear of always being watched and judged by a higher being—only now, she doesn’t think of that higher power as God but animals. “Other beings who live on this planet are very aware of what we do here and how we behave and how it impacts them,” she says, noting that the genesis of her exhibition was imagining how climate devastation might look from the perspective of an animal or the spirit of an animal mediated by a shaman.

“Mediums or people that have access to the underworld across cultures is really fascinating, because this is basically someone who has access to personal and collective histories that we otherwise might not have,” she says. It might sound mystical, but Xa’s ambitions are firmly grounded. “Much of my work actually is very much rooted in what I think about on a day-to-day basis,” she says, explaining that for herself and others, she hopes spending time with her art leads to a more fulsome understanding of how to live in the world with care.

Perhaps this is what underpins Xa’s mixed feelings around being recognized for the Turner Prize—she can’t connect in earnest with an award for a contribution to one nation when her artwork responds to planetary concerns. No matter the outcome of the Turner Prize, Xa’s career continues to accelerate. In 2026, she will debut new work alongside existing pieces at the Esker Foundation in Calgary and Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto and mount an ambitious exhibition of entirely new art at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. “I’m very competitive with myself,” she says, but she feels more fulfilled working in communion with others than by entering into rivalry. From her perspective, that will surely deliver more rewarding gains.