Haida Artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas Challenges Conventional Readings of History

In comic-book parlance, the gutter is the blank space between panels: a linear road map that divides a story into neat, discrete compartments. To Vancouver-based Haida artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, who is currently sketching out plans for a two-by-four-metre mural opening in summer 2024 at the Vancouver Art Gallery in his signature Haida manga style, the gutter symbolizes how we box ourselves into states of opposition and isolation by focusing on conflict instead of common ground. Over the course of his more than 50-year career in art and activism, he has championed an expansive approach that seeks to break free from containment and embrace connection.

Born in 1954 and raised in a small fishing village in Haida Gwaii, Yahgulanaas describes himself as Haida by birth and Canadian by decree. With a Scottish father and an Indigenous mother, he embodies two identities often caught in ideological enmity. His maternal ancestors include master carver and painter Charles Edenshaw and revered weavers Isabella Edenshaw and Delores Churchill, so it follows that his aesthetic is firmly rooted in the Northwest Coast tradition of formline art, a pictorial style arranged around continuous curvilinear bands and ovoid shapes.

Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

Charazo Back, watercolour on paper, 22.5 x 18.5”. Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

Yahgulanaas works across sculpture, painting, drawing, and ceramics. His copper car hoods, which reference Haida precious metals traditionally exchanged during potlatches, are part of the permanent collections of the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where he is one of only four contemporary Indigenous artists represented. But he is perhaps best known for inventing Haida manga, a hybrid genre that draws inspiration from a variety of displicines with North Pacific origins, particularly Chinese calligraphy, Japanese anime, and Edo-period ukiyo-e woodcuts.

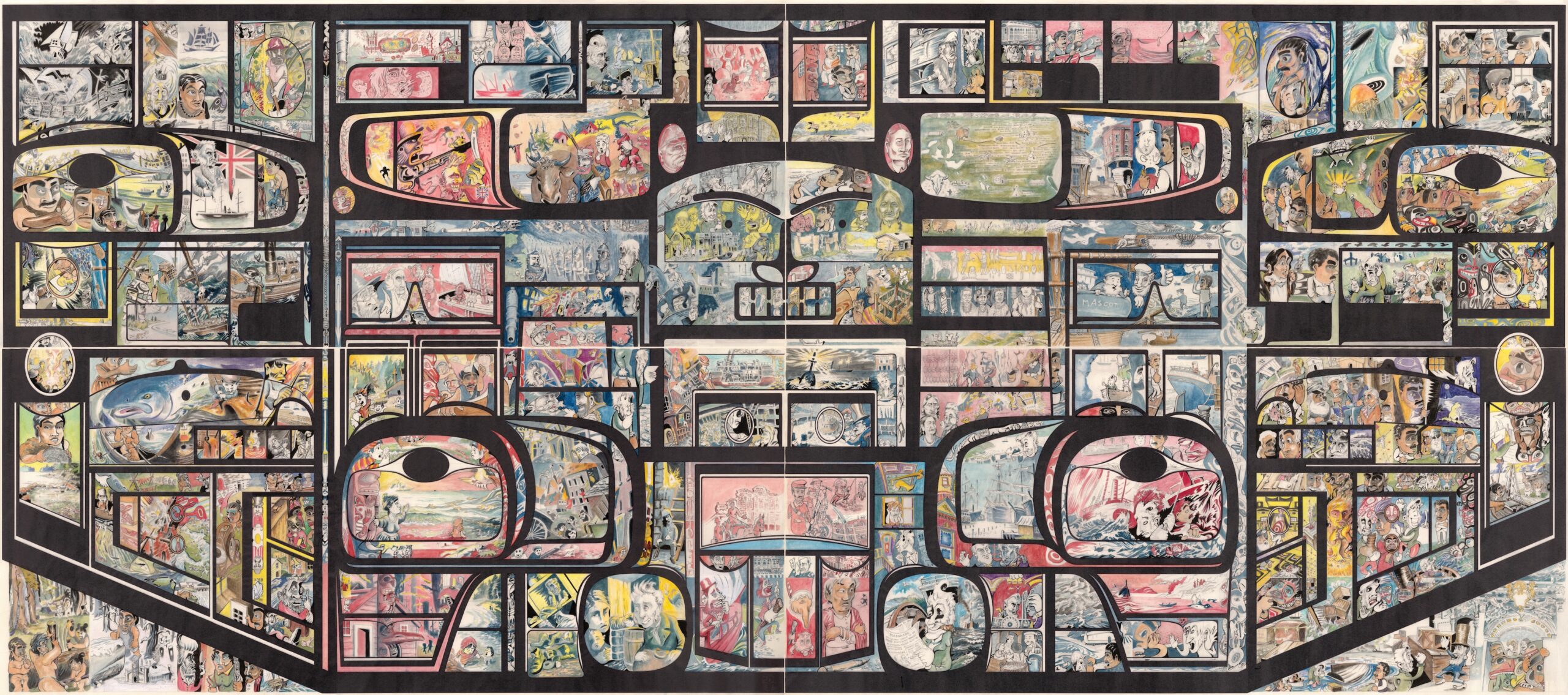

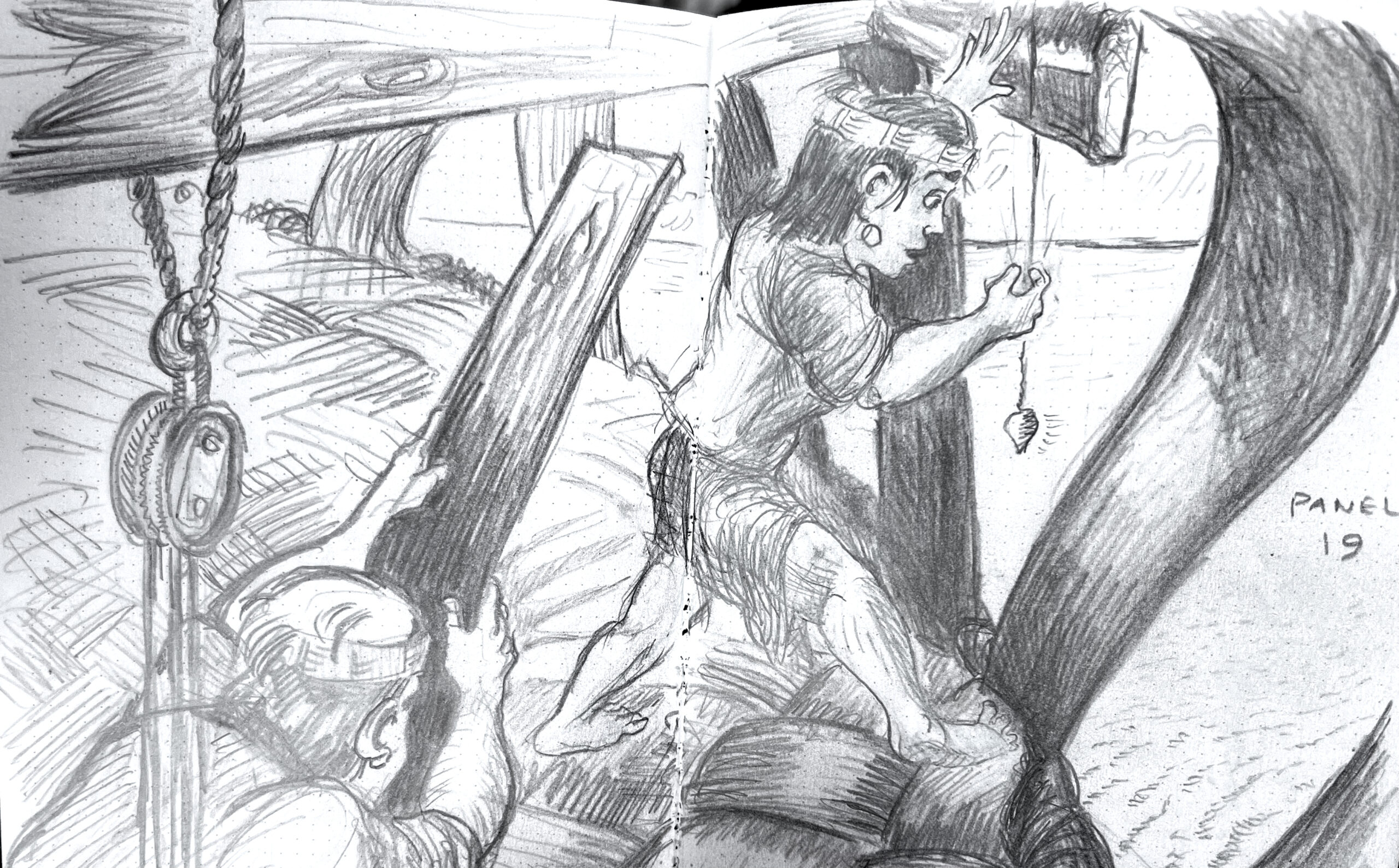

His original art form collapses the grid that has so sternly governed and patrolled the canon of Western art history. In vivid stories based on his own familial or cultural memories, which live in the graphic novels Red (2009), War of the Blink (2017), Carpe Fin (2019), JAJ (2023), and others, Yahgulanaas is guided by an Indigenous cosmology that is incongruent with conventional Western conceptualizations of time, space, or the relationship between the part and the whole.

“Our indulgent fascination with how significantly important humans are to the grand scale of the cosmos is beyond the absurd,” Yahgulanaas says. “This is the shaky foundation to a worldview in which we are always the good force subject to the obsessive focus of some malignant situation. This concept of opposing forces is the essential ingredient to the alarming deterioration of the planet, and if we remain trapped in this illusion, it appears to guarantee the end of the experiment called humans.”

In Haida manga, rectilinear borders are eschewed in favour of bold, undulating lines that can become part of the action, intersecting or melding with characters’ bodies. In using this technique, Yahgulanaas says, he intends to “defy your ability to experience story as a simple progression of events” and encourage readers to abandon the need for a “grand story to be obsessively concerned with the individual self.” Just as terra nullius never applied on the Indigenous land in what is now called Canada, the artist’s inter-panel lacunae do not recede into a vacuous cavity but unify with powerful life force.

JAJ, watercolour on mulberry paper, 2 meters x 8 meters (Mural for the Humboldt Centre in Berlin, Germany). Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

Best of Us, watercolour on paper, 21 x 17”. Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

When ripped out of their bindings and rearranged, the pages of Yahgulanaas’s pages jigsaw to create a larger composition resembling traditional formline art. This is also the configuration of his large-scale murals. Zooming out to the big picture reveals a beautiful interconnectedness that flows between all things, so completely omnipresent that it almost becomes invisible.

The Vancouver Art Gallery mural currently in development, titled Clan Hat, is the first of a trilogy. It will become part of the museum’s permanent collection and the opening chapter of a forthcoming 324-page publication. Yahgulanaas first began playing with the idea of this futuristic tale two decades ago. “This is a story of my entire fabrication, and considers the range and quality of relationships that individuals build to create functioning societies and how these structures respond to external challenges,” he says. “A hat is a good prop to consider that so many of our challenges and better possibilities are all within our heads.”

The adoptive homes of the next two murals in the series will require some looking toward the stars. With characteristic trickster eloquence, the nearly septuagenarian Yahgulanaas explains, “The production time is delayed as I am calibrating my advancing years while waiting for astrophysicists to develop some more coherent or at least comprehensible theories around black holes and time. Time distortion is a central element of the Clan Hat narrative.”