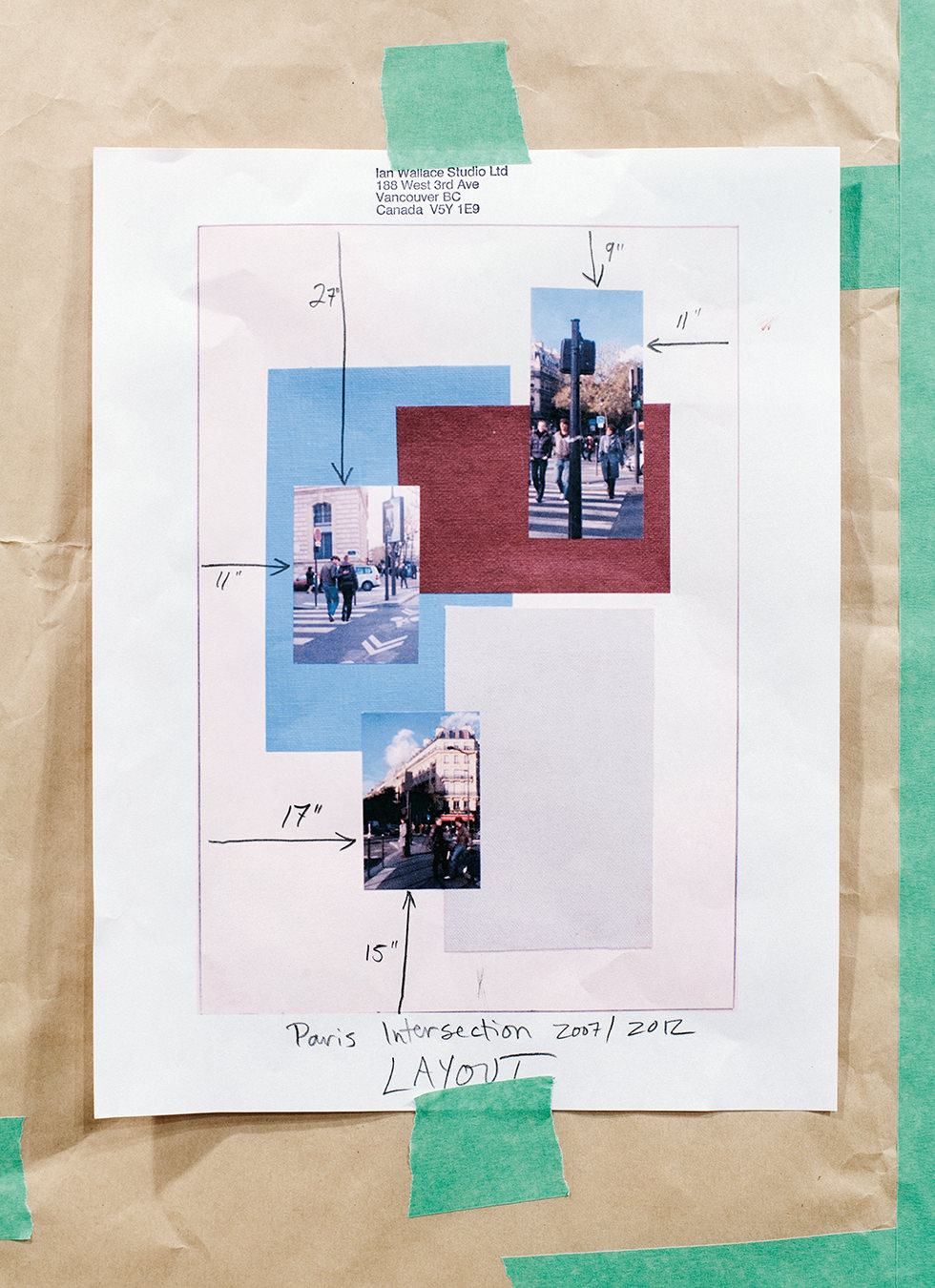

Artist Ian Wallace

World within world.

“I mean, look at it.”

I’m looking. “Yeah.”

“No. Really look at it.”

I’m not quite sure that I know how. But the man sitting on the sofa beside me—genial, soft-spoken, even decorous with his brand new Order of Canada pin on the jacket lapel—is the revered artist Ian Wallace, and so the pressure’s on. I dodge with questions. “Were those shots taken in Paris?”

“Yes,” he says, nodding. They’re photos snapped in his regular room at the Hôtel de Nice. A table in the foreground is strewn with pieces of paper, abstractly arranged. The photos themselves only take up a portion of the larger canvases, though, and all around those photos are larger blocks of monochrome colour, which repeat the shapes that appear on that desk. It’s a hall of mirrors, with the undefined qualities of solid paint reflecting the journalistic reporting of photography. “I wanted to make a work about making a work,” he says.

It’s hard to talk about art with Ian Wallace. Now 69, the man is a legendary figure in the galleries of Canada (and, indeed, the world). He’s often cited as the godfather of photoconceptualism, which is one of the more daunting, intellectual, and exacting territories of the art world. He is often lauded, too, for being a mentor to other “conceptual” greats like Rodney Graham and, most notably, Jeff Wall (“who taught me more than I ever taught him,” says Wallace). To view Wallace’s work is to invite an examination of one’s own understanding, alongside any examination of the artwork’s merit.

Since I’m worried about failing in Wallace’s estimation, I ask, “How do you feel about failure?” He seems to like the question.

“I wouldn’t say I’m afraid of failing,” he says. “What I worry about is embarrassment. That’s the only thing I fear.” He’s still looking forward at the three canvases showing that Parisian hotel room. “These are good. I think these are quite good. If I put out work that’s not good enough, that I can’t stand behind, that would be terrible. But it’s okay to fail, as long as I see the failure myself and stop the work from being completed. At this point in my career, I’m pretty good at spotting failures. And these,” he waves at the trio of canvases, “aren’t.”

The Paris pieces—which employ a Wallace hallmark in their juxtaposition of photographs and planes of monochrome paint—are his most recent work. So recent, in fact, they couldn’t be included in the two-floor retrospective that dominated the Vancouver Art Gallery this winter.

The VAG exhibit, Ian Wallace: At the Intersection of Painting and Photography, surprised me deeply. Like many, I had thought of Wallace’s work as being mostly quotidian portraits of street life—pedestrian in a literal sense, almost aggressively so, with slightly bored people navigating sidewalks in Vancouver, Los Angeles, Paris, or New York. But the show introduced me to earlier works that spilled over with romance and drama. An Attack on Literature I & II (1975) is a massive and moody installation of photographs that tell a story of a man and a woman, a writer and his muse, casting a kind of incantation on a stubbornly mute typewriter. Poverty (1980) is cinematic in the extreme, even operatic, made up of black-and-white photographs of downtrodden protagonists—they could be stills from the early days of cinema. And At Work (1983) took the romantic notion of the labouring artist to the nth degree when Wallace sat himself in the front window of the Or Gallery and read Søren Kierkegaard’s book The Concept of Irony while passersby looked in.

Ian Hugh Wallace, the eldest of four boys, was born (in 1943) in Shoreham, England—to Canadian parents. The family moved, when their son was only one year old, to the Okanagan region in the interior of British Columbia, and thence to North Vancouver, in 1952. Even as a boy, Wallace had some sense that a fellow could make a living in the art world: he painted portraits of kids in the neighbourhood and then sold them to beaming parents. But it would be many more years before his trajectory became established. “I did go into art classes in high school,” he says. “But they were pretty lame—the point was more that all the good-looking girls took art.”

Wallace’s art, like a confident stranger, doesn’t fall over itself to win approval while shaking hands, but it becomes a great companion on closer acquaintance.

His focus in high school, and later while he studied at the University of British Columbia, was always literature and poetry (today we see text, the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé, for example, incorporated into his canvases). And even when Wallace finally turned the lamp of his attention onto the art world, it was art history that held his gaze. After his marriage to Coleene Youche when he was 20, and the arrival of a son, Cameron, when Wallace was 21, his arrival at UBC’s graduate program in art history in 1966 was the manoeuvring of a serious young academic as much as a serious young artist, and both personalities were intent on making their mark. Indeed, the 23-year-old had seen his work exhibited at the VAG once already, and at the Victoria Art Gallery, too.

Before he’d even completed his master’s degree, Wallace was hired as an instructor of art history at UBC. And almost immediately, Wallace saw his interests clash with the academic majority. “Art historians then—and sometime still now—simply weren’t on the same track as the artists themselves,” he says. “They had a separate academic set of criteria for what could be talked about.” Fortunately for Wallace, the visionary modernist B.C. Binning happened to run the department back then, and he was happy to let this ambitious prodigy produce a new program that specifically taught contemporary art. Only because of that happenstance did Wallace’s young students become exposed to a breadth of new work. In a pre-Internet world, a worldly professor that could tie far-flung Vancouver to the wider world was invaluable. “I kept on flying here or there and would bring back slides, so they always knew what was going on.”

In 1972, Wallace took the post that would define his teaching career, at Emily Carr University of Art + Design (then the Vancouver School of Art), where he would teach art history for the following 26 years. The early career was punctuated by time abroad in London, a road trip circumnavigating North America, and a stint to Los Angeles managed entirely via hitchhiking. Just as Wallace is both a man of his time and one hovering in a far larger art-history context, he has also remained a happy Vancouverite while maintaining a global purview.

Perhaps maintaining a tandem between the local and the global, the immediate and the historical, is as good a way as any to look at Wallace’s work. The later pieces, which felt cold to me before, begin to warm up in context. Wallace’s art, like a confident stranger, doesn’t fall over itself to win approval while shaking hands, but it becomes a great companion on closer acquaintance. Certainly, one of the fires that conceptual work like his has kindled is the critical rage to bestow meaning through intricate analysis and historical comparison, rather than relying on gut reactions alone.

Then does the viewer—used to instant gratification—have a responsibility to do some homework before he or she comes to the gallery? “Actually, no,” he says. “I mean, anyone can take something from it. I think there’s a rigour, a conceptual rigour, in my work. Sometimes it can be difficult, but there’s also an openness in the imagery. I always want there to be several levels of interest. So: Is it pretty, do you like it, is it decorative? But also, what’s going on? What is underneath?” No schooling required, then? “The viewer only has to have the interest, I think. The art is a gift, not a responsibility.”

That gift can, perhaps, best be understood by a series of Wallace canvases that give the reader some insight, some access, into the world where the artist lives—the viewer is given, in many Wallace pieces, a backstage pass.

The artist at work in his studio was a major theme in the VAG retrospective. For decades now, Wallace has been documenting the process of his own art making in meta artworks that aren’t mere studies or sketches, but full-fledged offerings that fall in line with a long tradition in which artists have “caught” themselves at work—think of Vermeer painting himself as he paints another’s portrait, or Goya, who painted himself smiling around his canvas, into a mirror.

The 1979 Wallace work In the Studio is built of three photographs: there’s the cluttered, well-used bookshelf (teeming evidence of mental activity); then the Spartan desk and chair, with a couple of splayed books, abandoned mid-read; and (between those two) a shot of Wallace, himself. This middle image is both romantic and unexpected. Wallace is not splattered with paint, nor hunkering behind a camera lens. He is fiddling with papers, shifting things around on a desk full of words and images.

This new idea of what an artist looks like “at work” (sans smock, sans paintbrush, sans brooding brow, too) is exemplified in the 2008 reiteration of At Work. Although Wallace sat in the Or Gallery window for the 1983 version, the 21st-century take is a massive series of canvases picturing Wallace preparing in his studio. In a series of diptychs, Wallace is accompanied by a plain white desk, a photo of a street scene unscrolled on the concrete floor, a trio of blank canvases against the wall, and a bright yellow ladder that reaches forever out of frame. We see Wallace at his laptop, or reading from papers. In one image, he simply stands, arms akimbo, and stares at the unyielding white of those empty canvases. The important thing is the moment before creation, the gathering of thought. Though most of us think we’re being clever by measuring twice and cutting once, Wallace is a man who measures a hundred times (and then measures the measurements).

The conceptual artist at work, then, looks a lot like a philosopher at work, or a poet. One is reminded—considering the focus Wallace gives to preparatory moments, moments of becoming—of so-called horizontal writers like Truman Capote who claimed to do the bulk of their “work” while smoking on a sofa or drinking tea in bed.

There are, though, Mardi Gras moments to lend some relief. While Wallace and I talk on the sofa, he gestures over to a set of drums in the corner of the studio (a drum set I recognize from its appearance in a 2010 work of his called Work in Progress). “Some of us will jam over there in the evenings,” he says. “But, you know, it’s entirely improv. We don’t have set pieces. Someone will just start and the others have to join in and make it work. We’re just amateur.” The drums are the exception, then, that proves the rule around this studio, where nothing much is left to chance.

“I think there’s a rigour, a conceptual rigour, in my work,” says wallace. “sometimes it can be difficult. but there’s also an openness in the imagery.”

Not that Wallace’s studio could be called a stressful place, either. Far from it. Tucked amongst the light industrial buildings of Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant, it’s a world of chamomile tea, ample space, and unhurried conversation. Here and there, there’s a bottle of something to warm you up on long nights. Past a short row of computers staffed by assistants, there’s a den, a real cave, where the walls are made of bookshelves and Wallace can marinate in his thoughts by lamplight. It’s the sort of mental retreat that writers dream about possessing.

But I realize, talking with him, that I’m sidestepping the finished works in the studio; if a painting is “about” process, that doesn’t mean that the trappings of process are the work. (When Wallace shows me a photo of a stepladder that he works with, I ask whether the stepladder itself would ever appear in a gallery, and he shakes his head: that would never occur.) There is the studio and there is the gallery, and even these works that play with the difference do respect the border. A person can get trapped by the finality of a show, of course. “I’m a little wary of the way people might think of that VAG show,” says Wallace, smiling. “I mean, I hope they don’t think it’s a complete vision of a life’s work.” He straightens himself on his cushion. “I have 20 more years of work, I think.”

Like I said before, it’s hard to talk about art with Ian Wallace. But only at first. Then you realize it isn’t a test; he isn’t asking for a recitation of ornate theories, he isn’t waiting to see if you catch the references to the poetry of Mallarmé and bill bissett. He’s just asking you to look at the canvas on the wall. No. Really look at it.

And then be honest about what you see. Wallace may be one of Canada’s greatest art teachers—he is legend at Emily Carr, where he essentially invented their art history program and spent most of his teaching life—but he himself never went to art school. And having grown up with 1960s student politics, he’s soundly disinterested in the rage for credentials that dominates contemporary education. “If you’re looking for real credentials, the best come from one’s own autodidactic approach,” he says.

Inspiration comes, in the end, from the wide world, not ivory towers. One of the most memorable pieces at the VAG show was called, simply enough, Magazine Piece (1969/2012). The pages of a November 18, 1969, issue of Look Magazine were unbound and mounted in a strip that crawls around the room, surrounding the viewer on three sides with a continuing banner of lifestyle stories and glossy advertisements. A simple piece of masking tape held the pages together and to the wall. It almost seems a kind of joke; insert one comma and the magazine’s title becomes a command, a directive: “Look, Magazine.”

Like all great artists, Wallace invites (or cajoles) us to look and look hard. Not just at gallery walls, but at the magazine in our lap, the faces of strangers, the whole messy, in-progress world. From the vantage of his studio, the world outside feels very present and very distant at once.

When it’s time to leave, Wallace shakes hands again—very warmly—and, pointing at a labyrinth of storage, asks me, “Can you find your way out?”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.