In the race to find a greener, cleaner power source for our rapidly warming world, hydrogen has thus far been overshadowed by a multitude of other solutions.

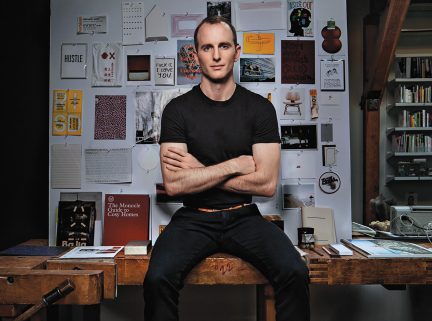

James Dolan

Canada’s Helium Boom: How the Country Is Emerging as a Global Supply Powerhouse

With new reserves, government backing, and rising global demand, the Great White North is positioning itself as one of the world’s most reliable helium suppliers.

Woman’s Brain Health Initiative Wants Us to Rethink Aging

As the Toronto-based organization points out, the gender-related causes of the ailments that interfere with cognition have too often been overlooked, taken for granted, or outright ignored.

Rooms With a Boo

The Fairmont Hotel Vancouver offers guests a supernatural experience.

Rolling With the Punches

Michele Romanow embraces failure on the way to business success.

What Happens When AI Comes for Popular Music?

As the rise of streaming makes it difficult for anyone who strums a guitar to make a living, it was only a matter of time before AI-literate producers found a way to turn artificial music into real profits.

UBC’s New Building for Biomedical Engineering May Spark an Entirely New Industry

Engineering excellence.

Pickleball Joins the Big Leagues

What is all the racket about?

Northern Lights: A New Generation of Airships Could Soon Be Flying in Canada’s Arctic

A look at Canada’s Inuit-owned airline Canadian North.

Are Classroom Cellphone Bans Actually Working?

Phone fight.

Scientists Are Working to Make the Ocean a Quieter Place

The louder things get underwater, the harder it becomes for whales, dolphins, fish, and other species to navigate and communicate with their kind.

Family Fortune

The Great Wealth Transfer will change Canada’s economy. And maybe Canada itself.

Alberta’s Fight Against Rats Holds a Big Lesson for Us All

Over the years, Alberta has achieved the near-complete absence of Rattus norvegicus—the Norway (or brown) rat.

Artificial Intelligence Is Putting Ever-Increasing Demands on Our Resources

Recent estimates suggest a typical query from ChatGPT consumes about the same power as it takes to light a standard seven-watt LED bulb for about 20 minutes—roughly 10 times as much as a Google search.

One of the World’s Most Sustainable Materials May Break Our Addiction to Everything Unsustainable

Cork is now used for everything from home insulation to shoes to floor tiles to engine gaskets to, in at least one instance, postage stamps.

Saving the Earth Starts With Building a Better Battery

Any effort to “electrify” our carbon-addicted world will come down to a technology most of us take for granted: the humble battery.

A New Treatment Cures an Old Disease—and Possibly Many Others

Casgevy is the world’s first government-approved, effective gene-edited cell therapy to treat sickle-cell disease.

High-Tech Wood Skyrises Might Help Heal the Planet

Over the past decade, scientists, engineers, and architects (many of them Canadian) have used advanced technology to challenge wood’s limitations.

The Pioneering Study Solving Jet Lag

Researchers from the University of Sydney and Australian national airline Qantas—which, given its home base, flies plenty of long-haul flights—recently undertook Project Sunrise, an extensive in-air research project that aims to lessen the suffering of the long-distance traveller.

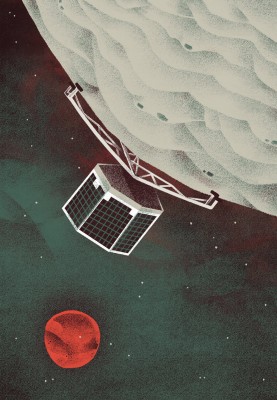

Deep Space Medical-Care Challenge Aims to Make Deep Space Healthier

Ask the rocket man: it’s lonely out in space. Turns out it’s more than a little unhealthy too. It’s not just the difficulty of finding a pharmacy on the International Space Station or a doctor’s office on the moon. Astronauts have to contend with the absence of gravity, the threat of gamma rays, the lack of physical activity, and the mental strain of months away from solid ground. All of it combines to make being a deep space explorer one of the most hazardous jobs on Earth. Or off it.

ChatGPT Attempts to Make Artificial Intelligence Live Up to Its Name

For the record, the sentence you are currently reading was not written by ChatGPT. Nor was anything in the magazine you’re holding. But that newspaper over there, that recipe you downloaded for last night’s dinner, the blurb on the toothpaste package, the radio ad you listened to on the drive home, that essay your neighbour’s son just handed to his prof—well, who knows?

UBC Researchers May Have Just Made Styrofoam Obsolete

How problematic is expanded polystyrene, the scientific name for what most of us know as Styrofoam? Let us count the ways.

The First Energy-Positive Fusion Reaction Sparks a Whole Lotta Hope—and Hype

Finally, we did it. Some 4.6 billion years after the hydrogen molecules first smashed together deep within the sun, scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California succeeded in creating a controlled nuclear fusion reaction that produced more energy than lasers delivered to it.

The Pros and Cons of Carbon Capture Technology

You can see the appeal of the idea: instead of immediately cutting our use of oil, coal, natural gas, and other fossil fuels, we wean ourselves off gradually, stashing their planet-warming CO2 emissions underground until we figure out how to kick our addiction.

Big Countries Are Making Big Moves to Secure a Homemade Supply of Microchips

It’s not every day you see the U.S. Congress playing three-dimensional chess. But that’s a good way to think about the $280-billion CHIPS and Science Act: the latest move in a contest that is highly strategic, deeply considered, and focused on an end-game far from the here and now.

New (and Old) Strategies to Combat One of Humanity’s Oldest Foes

Warming temperatures, ongoing drought, and urban sprawl are forcing the world to confront one of the oldest technologies: fire. In the modern era, instead of trying to understand wildfire, studying our vulnerabilities to it, and changing our behaviour, we have kept doing the same things, assuming water and fire retardant will solve the problem.

Quantum Computing Stands to Change Everything You Know About Technology

Postmodernism. British cuisine. The ongoing popularity of the Real Housewives media empire. There are some things in heaven and earth that are just hard to wrap your head around. Add quantum computing to the list.

The United Nations Tries to Clean Up Plastic Waste

If you’ve been to the beach lately—or gazed at the roadside, walked through a typical downtown, or been pretty much anywhere on the planet—you’ve no doubt noticed the world has a bit of a plastic problem: there’s too much of it. So much so that scientists estimate the mass of all plastic ever produced now surpasses that of all creatures on the planet.

Hackers, Activists, and Entrepreneurs Fight to Keep the Internet On

From the so-called Great Firewall of China to service providers throttling download speeds to Russia’s recent attempt to permanently log itself out of Facebook, Twitter, and other social media, the free, open, and globally accessible World Wide Web isn’t exactly living up to its name.

Biodiversity and Its Implications for Your Morning Latte

You have water shortages to contend with. Soil contamination. Deforestation. There’s coffee rust, a withering fungus that can kill up to 80 per cent of a plant’s leaves. And of course, the growing peril of climate change.

Metaverse: Humanity’s Techno-Evolution

Recently, a bunch of would-be digital land barons have planted their flags on a variety of online spaces, staking ownership to properties in the so-called metaverse before the rest of us are even sure what the word means.

A New Weapon in the Millennia-Old Fight Against Malaria

News flash: malaria is still with us. News flash number two: maybe not for long.

The Whitest Paint Ever Could Be a Useful Tool to Fight Climate Change

Now, in addition to its creative nomenclature, white paint has another thing going for it: it might just slow climate change.

Welcome to the Age of Space Tourism

Ticket prices won’t be the only way that space tourism will be expensive.

News Parody Sites Remind Us of What’s “Really” Important in a Post-Truth Age

But—must reading the front page make us want to toss the newspaper away and cover our head with a soft blanket?

The Art and Economics of NFTs, Non-Fungible Tokens

On some level, this fetish of authenticity is difficult to fathom.

Some Technological Challenges, Solutions, and Implications of Vaccine Passports

After 18 months of lockdowns, work stoppages, and stay-at-home orders, you knew that sooner or later you’d actually have to prove that yes, you actually have been vaccinated against COVID-19.

Coinbase, the World’s Premiere Cryptocurrency Exchange, Faces Contradictions Since Going Public

For all these services, Coinbase charges a variety of commissions, functioning as the classic “toll booth” on the trading superhighway it built.

Why European Football’s Not So Super League Got Ejected Before It Even Started

Why Europe’s fans rejected this new league and what that means for the sport in general.

Telling the Story of Gamestop: One of History’s Most Infamous Short Squeezes

GameStop stock’s meteoric rise (up 2,500 per cent in two weeks) has become an example of everything wrong (or right) with the economy.

How Regenerative Agriculture Will Change the Way We Eat for the Better and Help the Planet

In a lot of ways, regenerative agriculture is less of a new idea than it is a return to age-old farming techniques.

How Lockdowns and Stay-at-Home Orders Have Focused Our Attention on the Noise of the City

The culture of modern life usually considers silence to be a lack: a deficiency or void in the action and energy that is civilization’s natural state.

Low-Carbon Cement Makes a Dent in Climate Change, One Slab at a Time

It’s probably been awhile since you thought about cement. And by “awhile” I mean, well, ever.

A New Weapon In The War Against Cancer

Researchers at the University of Glasgow have developed a new weapon in humanity’s ongoing war against cancer.

The Challenges of Getting Physical Exercise in an Age of Physical Distance

It’s funny—it has taken restrictions to highlight an essential truism about any workout routine: that the first and most important exercise takes place in the mind.

Sports Is Dead. Long Live E-sports.

Since COVID sent the world’s professional sports leagues into a months-long time out, broadcasters have been scrambling to fill the time.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Gets a Little Smaller

We now interrupt your regularly-scheduled panic about burning forests, melting sea ice, and smog-choked air with a bit of good environmental news: the ocean will soon be a little cleaner.

Can We Save the Banana from Extinction?

There’s a problem over in the produce aisle: they’re running out of bananas.

The Evolution of Your Liquor Collection

If you want to know someone, ask them about their politics. But if your goal is to understand someone—how they think, what they value, how they view the task of moving through this life—ask them what’s in their liquor cabinet.

Why Adults are Reading (and Rereading) Young Adult Fiction

News flash: all those people ripping through the pages of the Harry Potter novels, the Divergent series, and the Hunger Games trilogy—on their lunch break, on the train home, during that layover at Pearson—not all of them were teenagers.

Is Geoengineering the Answer to Climate Change?

Climate changing a little too fast? No problem: just change it back. That’s the basic idea behind geoengineering.

Porsche’s 2020 Taycan Makes an Electrifying Statement

Porsche would like to set the record straight on a couple of things. Number one: it makes the best cars on the planet. Number two: don’t you ever forget number one.

When Words Fail: The Emoji Era

Since their emergence on Japanese cellphones some 19 years ago, emoji have become a standard feature of conversation in the digital age.

High Tech, Higher Purpose

Earlier this year, a group of 21 prominent universities united to form the Public Interest Technology University Network, a group putting forward a collaborative, open-source approach that views high tech through the lens of social, ethical, legal, and public policy implications.

The Universal Disdain for Comic Sans

Understanding the woefully inartistic and ridiculously misused typeface: Comic Sans.

An Era of De-cycling

For years, recycling in the Western world has been based on the idea that we can simply stuff our dirty plastic, obsolete electronics, and broken toys into a shipping container, and send it to the other side of the world. Until now.

Google Street View in Canada’s North

Google loans its iconic 360-degree trekker camera to Parks Canada as part of an ongoing push to bring the whole country to Street View.

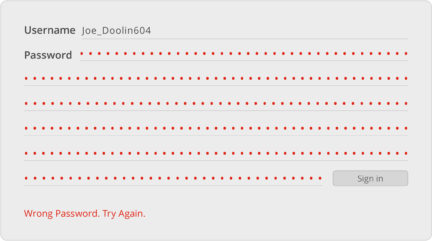

The Folly and Frustration of Creating Passwords

A look at the worlds most common passwords—ranging from sequential numbers to the word ‘password’ itself—bring to light a new age of digital apathy, where our most personal information is thinly blocked by our most lacklustre passwords.

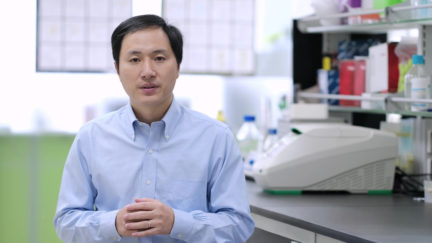

The New Generation of Gene-Editing Technology

Biophysicist He Jiankui navigates the delicate science of gene-editing, but how much of a reality is the complex process for the next generation?

Unlocking the Luxury Lifestyle with Keyyes

Sarment, a Singapore-based tech start-up, wants to make the process of getting in on a good thing a little less difficult.

The Economics of Celebrity Endorsements

These days, the endorsement game faces a challenge: the erosion of the aura that surrounds fame.

How High Tech Tackles the Problem of Food Waste

From waste monitoring apps to smart packaging to new ways of harvesting bioenergy from old food, tech start-ups are focusing on solving the problem of food waste.

When There’s A Will

A rite of passage, a lesson in wisdom, an essential reminder.

Cape Town’s Water Crisis

Cape Town, the second largest city in South Africa, has a bit of a problem: it’s running out of water.

The Graphic Novel Gets Political

Graphic novels have quickly become a favourite means of conveying under-represented, non-privileged viewpoints.

The Bitcoin Hype

Developed in 2009 as an unregulated, decentralized payment system that bypasses banks and other middlemen, bitcoin has become perhaps the definitive example of financial speculation.

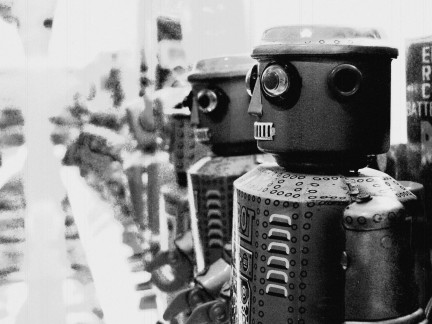

Men (Not) at Work

Robots are expanding past their home on the factory floor and starting to threaten human employment in a variety of professions.

A First Look Inside Parq, Vancouver’s Destination Resort

Situated just south of BC Place Stadium, Parq is the largest private development in the province and a stunning example of how a new crop of architecture seeks to transform Canada’s City of Glass.

Concussion Diagnosis

A new app puts professional-level concussion diagnosis in the hands of amateur coaches and officials, parents, or anyone with a smartphone.

Toronto’s Guerrilla Archivists

Instead of donning Guy Fawkes masks, a group of Toronto-based online activists are fighting the power by playing librarian.

Wells Fargo: Good Bank, Gone Bad

Why open accounts for people who don’t want them? Simple: survival.

The World’s First Cybathlon

The Cybathlon is a different sort of competition, in which performance enhancement is not only perfectly acceptable, it’s actively encouraged.

Hyperloop Transportation System

A super-speed levitated transportation system that uses magnetic accelerators to transports passengers at a projected top speed of around 1,200 km/h.

Data After Death

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Derek Miller is dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that—because Miller himself told us. His final words, uploaded posthumously by a close friend on May 4, 2011, were both pithy and poignant: “Here it is. I’m dead, and this is the last post to my blog.” He was 41.

The Economic and Social Cost of the Panama Papers

The Panama Papers are less about rich vs. poor, haves vs. have-nots, and more about all-in-this-together vs. every-man-for-himself.

Brexit Stage Left

Dramatic. Momentous. Revolutionary. Earth-shattering. Such peacockery has typically been confined to Hollywood puff pieces and high-tech product launches, until now.

Joe Gebbia of Airbnb

To co-founder Joe Gebbia, what Airbnb is actually selling is a kind of antidote to a peculiar sense of 20th century alienation.

Proof for Gravitational Waves

Did you feel that? That little stretch as your legs pulled away from your body, that little squeeze as your sides squished together for a fraction of a moment?

Brazil’s Recession Troubles

The most depressing part of the story: it’s the same old story.

Wheels Up

Wheels Up isn’t the only company offering private aviation. But they do business differently, functioning more like a private club than an ownership group.

Battle of the Bytes

The script reads like something Spielberg would have cooked up back in the eighties: a nefarious group of black-hooded malcontents arise from the desert, hell-bent on burning Western civilization to the ground.

Bang Goes the Buck

China fired first. Maybe it was Brazil. It could have been Mexico. Or perhaps Japan. Whoever pulled the trigger, one thing is certain: the currency war is on. And the one who can debase their money furthest, and fastest, wins.

Car Hacking

You’re behind the wheel when suddenly the radio starts blaring—strange, because you just shut it off. Then the turn signal turns on. Your pulse picks up; you wonder what the heck is going on—and that’s when the engine cuts out.

Stanford Scientists Create Artificial Skin

Robot? Pshaw. Anyone can build one of those. But how about one that can feel?

SecuriPhone

When hackers bust into your phone, you could go after the hackers. Or, you could go after the phone—by building a new one. At least, that’s what the mandarins in the People’s Republic have decided to do.

Everything Was Awesome

Down in the basement there’s a box. The box is a bit of a contradiction, made of ordinary cardboard, but filled with the most extraordinary things: houses and castles, cars and trucks, monsters and machines both real and fantastic, all crafted from a wonder-filled geometry of multi-coloured bricks.

The Chinese Economy

Let’s be clear about one thing: the explosion was real. Fully 173 people lost their lives; a further eight remain unaccounted for. The blast levelled the commercial heart of the city, damaging 17,000 homes and destroying 3,000 vehicles.

The Doctor Is In

Thirteen years, three billion dollars. That’s the size of the investment made to map the human genome in its entirety, give or take a few months and a few million. While scientists completed the effort over a decade ago, we’re only starting to reap the returns.

Greek Tragedy

Odysseus had Scylla and Charybdis; in the present day, Greeks have been forced to choose between austerity and bankruptcy. The devil and the deep blue sea—either way, the chances of coming out in one piece are pretty slim.

The Art of the Deal

He is an imposing figure, this walking man: fully six feet tall, naked, his stick-thin limbs disproportionately long, his metallic skin clearly showing the rough handiwork of his creator.

The Darknet Side

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Ross William Ulbricht is in jail. And if the FBI has its way, he’ll be there for quite some time. The charges: drug trafficking, money laundering, computer hacking, and ordering a hit on a resident of White Rock, B.C., who had piqued his ire.

The Auto-Automobile

On the road of life, there are passengers and there are drivers. At least, there used to be.

Oil’s Big Collapse

It’s the way you feel after downing one too many Singapore Slings the night before: after years of binging on high oil prices, Canada’s energy sector is experiencing the mother of all hangovers.

Clearing the Air

And now for some good news: the ozone layer might actually be repairing itself.

A Cosmic Rendezvous

Small step or giant leap—call it what you will, it was historic.