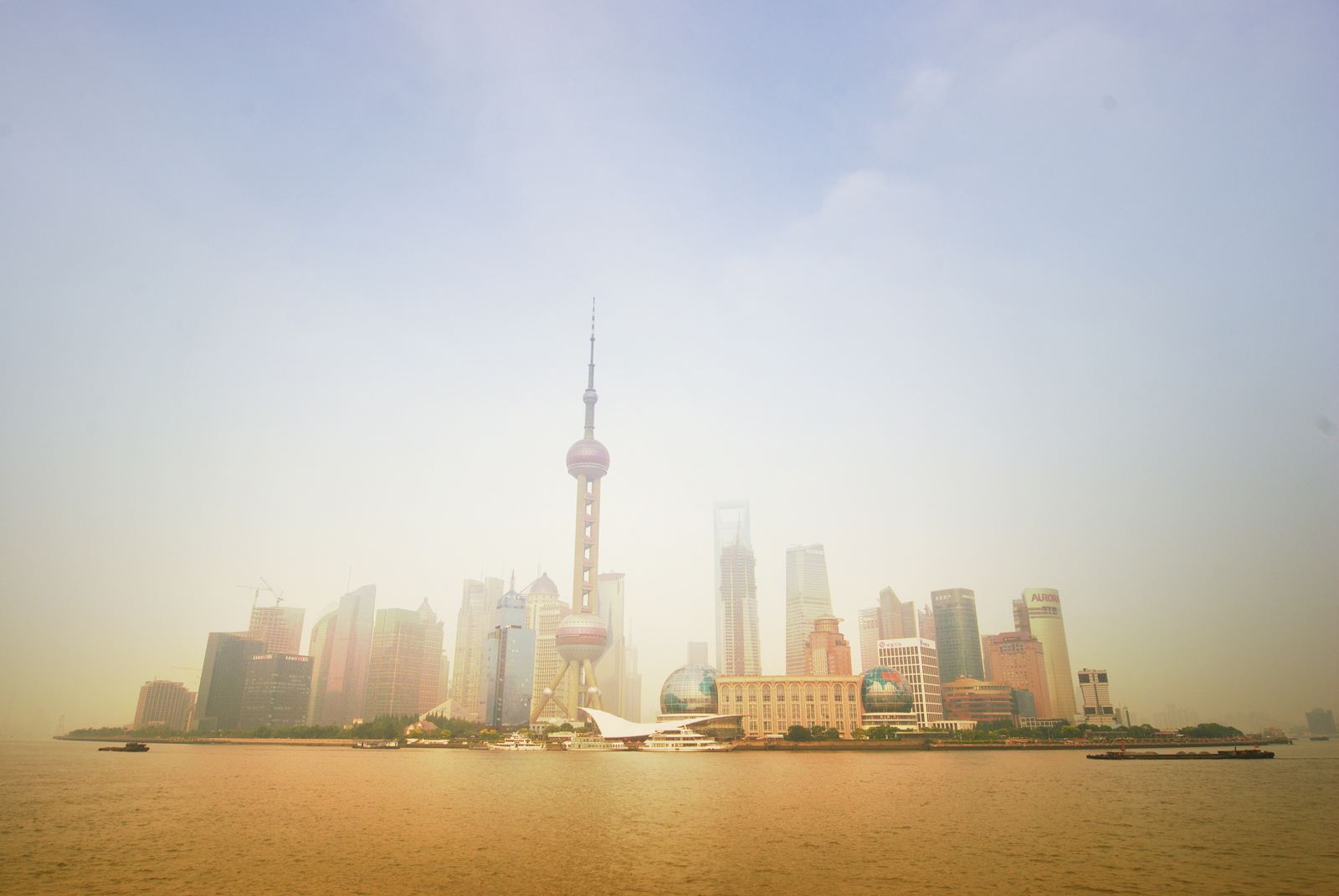

The Chinese Economy

Growing pains.

Let’s be clear about one thing: the explosion was real. Fully 173 people lost their lives; a further eight remain unaccounted for. The blast—equivalent to a magnitude 2.9 earthquake—levelled the commercial heart of the city, damaging 17,000 homes and destroying 3,000 vehicles.

It’s hard not to read the disaster at the Port of Tianjin figuratively—the fury of the blast serving as a fitting trope for what happened to the Chinese economy this past summer, and the stunned shock of the city’s residents an appropriate stand-in for what investors are feeling right now.

Economists and pundits have been predicting financial disaster of some form or another in China for some time. But after years of double-digit growth, no one much believed them. Stories of “ghost cities”; a multi-trillion-dollar “shadow banking” system; questionable bailouts of state-run enterprises; boundless corruption—none of it seemed to matter much as long as the factories kept humming, the money kept flowing, and the stocks kept climbing.

Rumblings that Chinese GDP growth had moderated from its typical pace drove panic selling on the Shanghai exchange. Then, out of the blue, the mandarins at the People’s Bank of China decided to devalue the Chinese yuan by 2 per cent—a small move, but more than enough to make traders jittery about a possible currency war. Next, in late August, China’s Manufacturing PMI (a key indicator of activity in the all-important manufacturing sector) fell to a 78-month low. Taken together, it all seemed to confirm investors’ worst fears: that business is anything but usual in the Middle Kingdom.

Of course, clarity remains elusive in China. Despite its size ($7.3-trillion; second only to the United States), the Chinese economy remains a closed one, and the connection between officially sanctioned data and life-on-the-street reality remains an open question. Even now, Beijing insists annual GDP growth will come in at 7 per cent. Investors remain skeptical, as evidenced by the mass dumping not only of Chinese equities but of any multinational damaged by weaker Chinese demand for raw materials or luxury goods.

In Tianjin, the rebuilding has begun. But here too the news can be read as metaphor. No one knows exactly what went wrong down at the port. Or how much was lost. Or how long it’s going to take to clean it all up. Neither do investors.