The Economic and Social Cost of the Panama Papers

Don't follow the money.

Death. Taxes. The endless, seemingly unholy awfulness of the Toronto Maple Leafs. For decades, these were the things Canadians could firmly believe in, the trifecta of issues that neither gods nor masters could hope to affect. But times change. Doctors find life-saving drugs. The Leafs find new management. And the overtaxed—some of them find lawyers.

Expensive ones, most of whom live on exotic islands with an abundance of blue water, white sand, and lax financial regulations. For the right price, you too can hire a gaggle of them to shuffle your money into and out of a web of offshore bank accounts, shell companies, and trusts so that the Canada Revenue Agency will be able to neither follow nor find it.

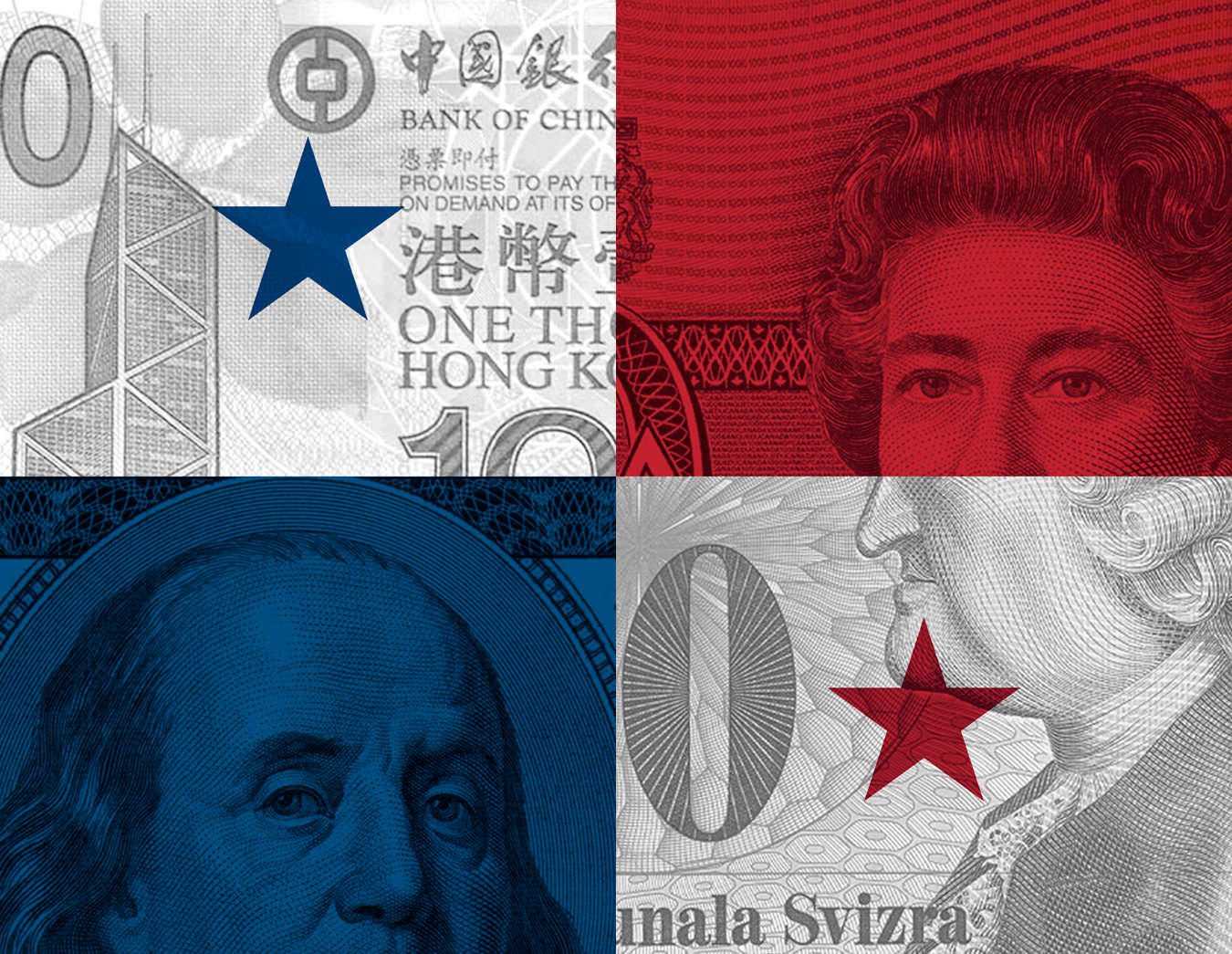

That’s the big take-away from the Panama Papers, a package of over 11 million e-mails, contracts, scanned documents, and other financial files leaked from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca last year. The first news stories were published on April 3, 2016. Taken together, the Papers function as a kind of master class in avoidance and evasion, outlining how some of the world’s wealthiest politicians, entrepreneurs, sports stars, entertainers, and others (including 625 or so Canadians) use the laws of far-off lands to hide hundreds of millions of dollars from ex-spouses, tax authorities, Interpol, or sometimes all of the above.

On one level, this is hardly news. Dodging taxes has been going on since, well, the creation of taxes. And let’s be honest with ourselves: it’s not only the wealthy who are in on the action. For every millionaire stashing his or her cash overseas, there are dozens, perhaps hundreds of Main Street Joes and Janes paying cash for kitchen renos, claiming suits as business expenses, or making that job for so-and-so “disappear” from the annual income statement.

It seems quaint to talk about the right and wrong of sticking it to the taxman—as if discussing morality and money in the same sentence were a conceit as old-fashioned as high tea. Taxes are too high; everybody else is doing it; a few bucks won’t matter; those fools in Ottawa would just waste it anyway; I earned it, so it’s mine—sure, rationalize if you must. But the real reason we might be tempted to perform a little nip and tuck on the annual return has more to do with simple greed than lofty principles.

For every millionaire stashing his or her cash overseas, there are dozens of Main Street Joes and Janes paying cash for kitchen renos.

Even so, it’s hard to read about the Panama Papers without feeling a little disheartened by the cynicism and entitlement on display. No, not all the activity therein is illegal. Nevertheless, there’s something about the secrecy and subterfuge of hoarding one’s savings in a confidential account in a lawyer’s desk somewhere in the Third World that doesn’t sit quite right: it may not violate the letter of the law, but surely it chafes against its spirit.

And then there’s the cost. Globally, governments lose an estimated $200-billion a year to the kind of financial engineering seen in the Panama Papers. Obviously, such actions have a staggering economic cost: $200-billion could build a lot of roads, schools, and hospitals; pay for an army of construction workers, teachers, or doctors; or seed a world-changing wave of high-tech innovation, industrial growth, or scientific research.

There is a social cost as well, for every society must be bound together in some way: shared culture, shared history, shared language(s), shared obligation for the maintenance of society itself. In this respect, taxes are part of the glue that holds a nation together. No taxation without representation, yes. But it works the other way too: without taxation, without an ownership stake in the country itself, how can you represent yourself as a citizen, a member of a larger whole sharing a common purpose with your neighbours?

Viewed in this way, the Panama Papers are less about rich vs. poor, haves vs. have-nots, and more about all-in-this-together vs. every-man-for-himself. Yes, we all have something to say about taxes, about how much to pay and what we pay for. But whatever our net worth, let us at least agree that to refuse to pay at all—to shirk one’s responsibility for the cost of civilization, all the while enjoying the most lavish of its benefits—this is a sign of privilege gone too far.

“Only the little people pay taxes,” Leona Helmsley reportedly said. The 1980s billionaire hotel heiress was infamous for both petty cruelty and large-scale tax evasion. Aye, there’s the rub: not the “pay” part, but the idea of there being “little people”. When we see a ring of misers play by different rules because they believe the rest of us (whether moneyed or not) too small willed or small witted to stop them, that is the point at which the social contract breaks down. The point at which anger drowns out discourse, and tribe trumps nation. The point at which the little people round Line 150 down by a few bucks, a few hundred, a few thousand. Because there’s no longer a reason not to.