Welcome to the Age of Space Tourism

Sky's the limit.

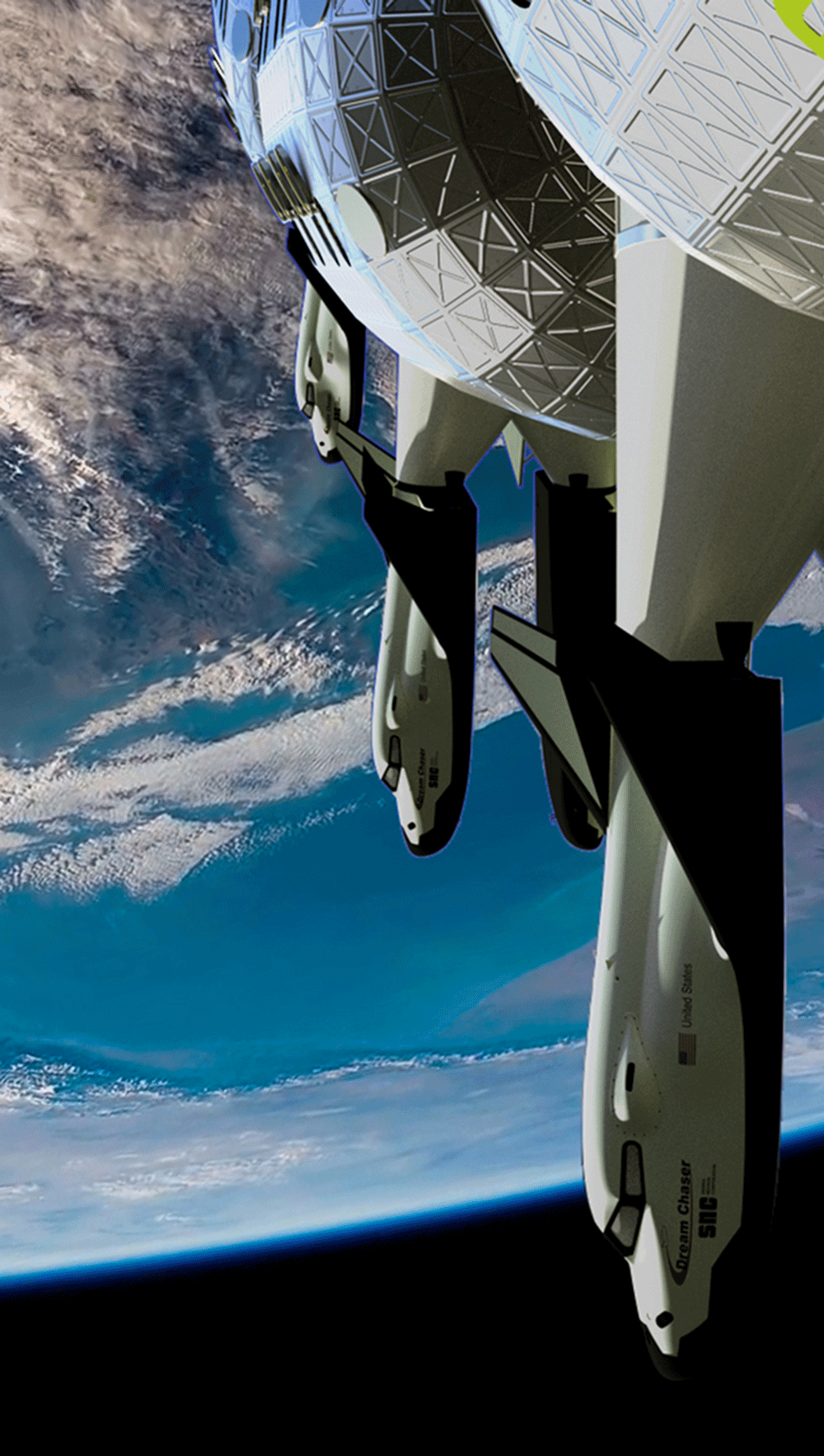

Credit: SpaceX via Pexels.

“Joy” isn’t an easy word to define. But you can see it, right there on Hayley Arceneaux’s face. As the cupola of SpaceX’s Dragon capsule opens to reveal the Blue Marble beneath it, the emotion behind Arceneaux’s smile—that mix of wonder and amazement and marvel and reverence all at the same time—is easy to understand.

After years of testing and prototyping, several companies seem ready to open up the skies to a new form of tourism, ushering in an age in which instead of relaxing on a beach with a pitcher of something fruity for a week, a new generation of wealthy explorers can blast off into the stratosphere and enjoy water and vacuum-sealed rations for a few days.

As vacations go, a holiday in the stars won’t be cheap. Virgin Galactic recently announced it will sell tickets on its VSS Unity space plane for about $450,000 (U.S.). Blue Origin, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, will charge between $200,000 and $250,000. Meanwhile, Houston-based Axiom has inked a deal with Elon Musk’s SpaceX to take visitors on a 10-day mission to the International Space Station for about $55 million apiece. Such prices make for a pretty good business. In fact, a 2017 analysis of the industry by Bank of America Merrill Lynch suggested the industry could exceed $2.7 trillion by 2050. All in all, there’s plenty for billionaire entrepreneurs to get excited about.

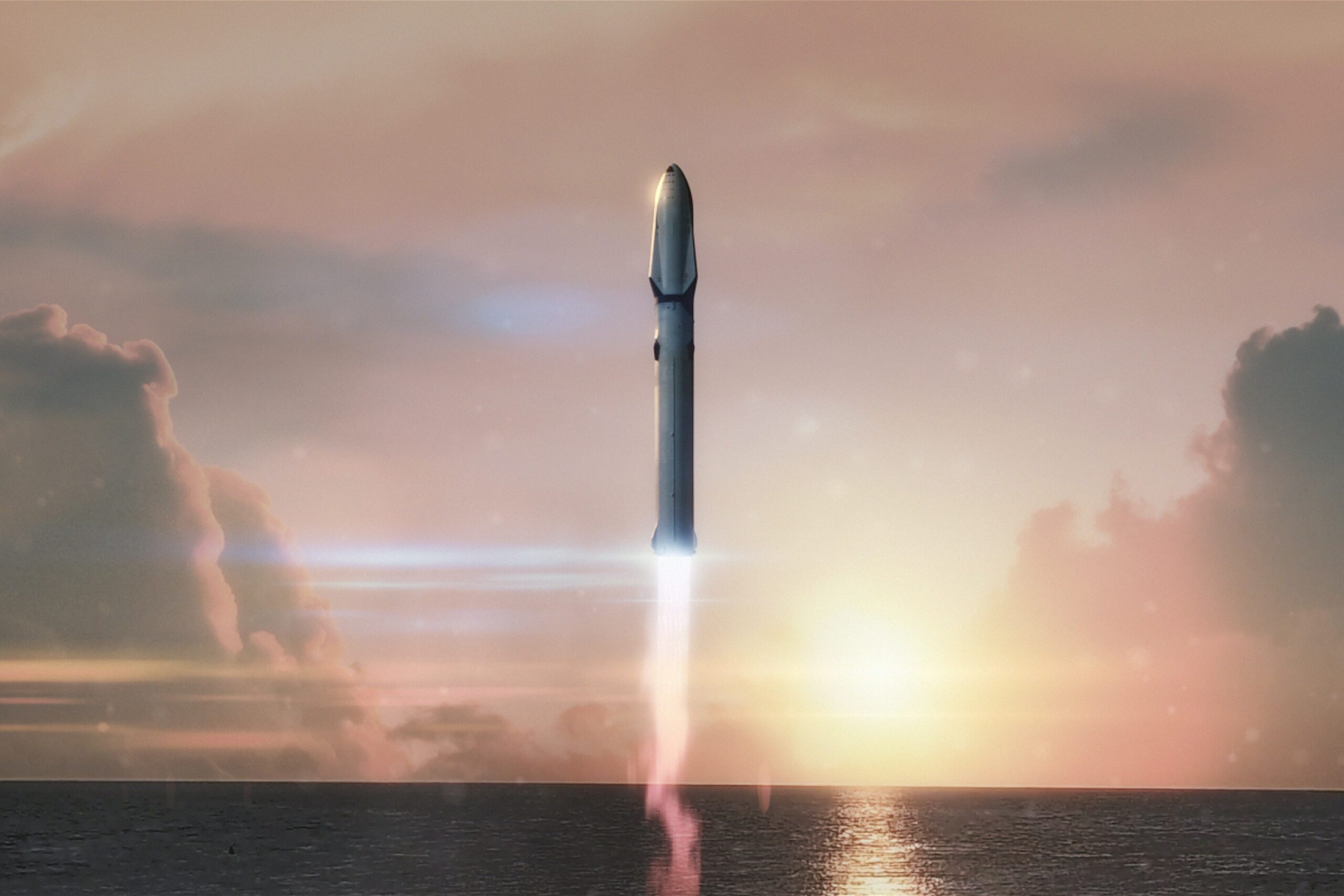

Ticket prices won’t be the only way that space tourism will be expensive. With a single rocket launch releasing between 200 to 300 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere (about the same as over 300 simultaneous transatlantic flights), it’s fair to say that as good as space tourism might be for space, it surely won’t be good for the planet. And all those gases and fumes coming out of the back end of a booster rocket aren’t exactly great either; some scientists suggest they could end up disintegrating the protective layer of ozone that shields us from cosmic rays and other harmful radiation.

With a single rocket launch releasing between 200 to 300 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere (about the same as over 300 simultaneous transatlantic flights), it’s fair to say that as good as space tourism might be for space, it surely won’t be good for the planet.

Such considerations may well take some of the joy out of the enterprise. Instead of intrepid, risk-taking explorers or thrill-

seeking adventurers or wide-eyed sci-fi fanatics, space tourists may end up being nothing more than symbols of the second gilded age: the perfect reminder of the extreme heights the well-to-do have risen above the rest of us—some 408 kilometres above, to be exact. And the burgeoning business of space tourism is a reminder that for most of us, the final frontier may be the biggest glass ceiling of all.