UBC Researchers May Have Just Made Styrofoam Obsolete

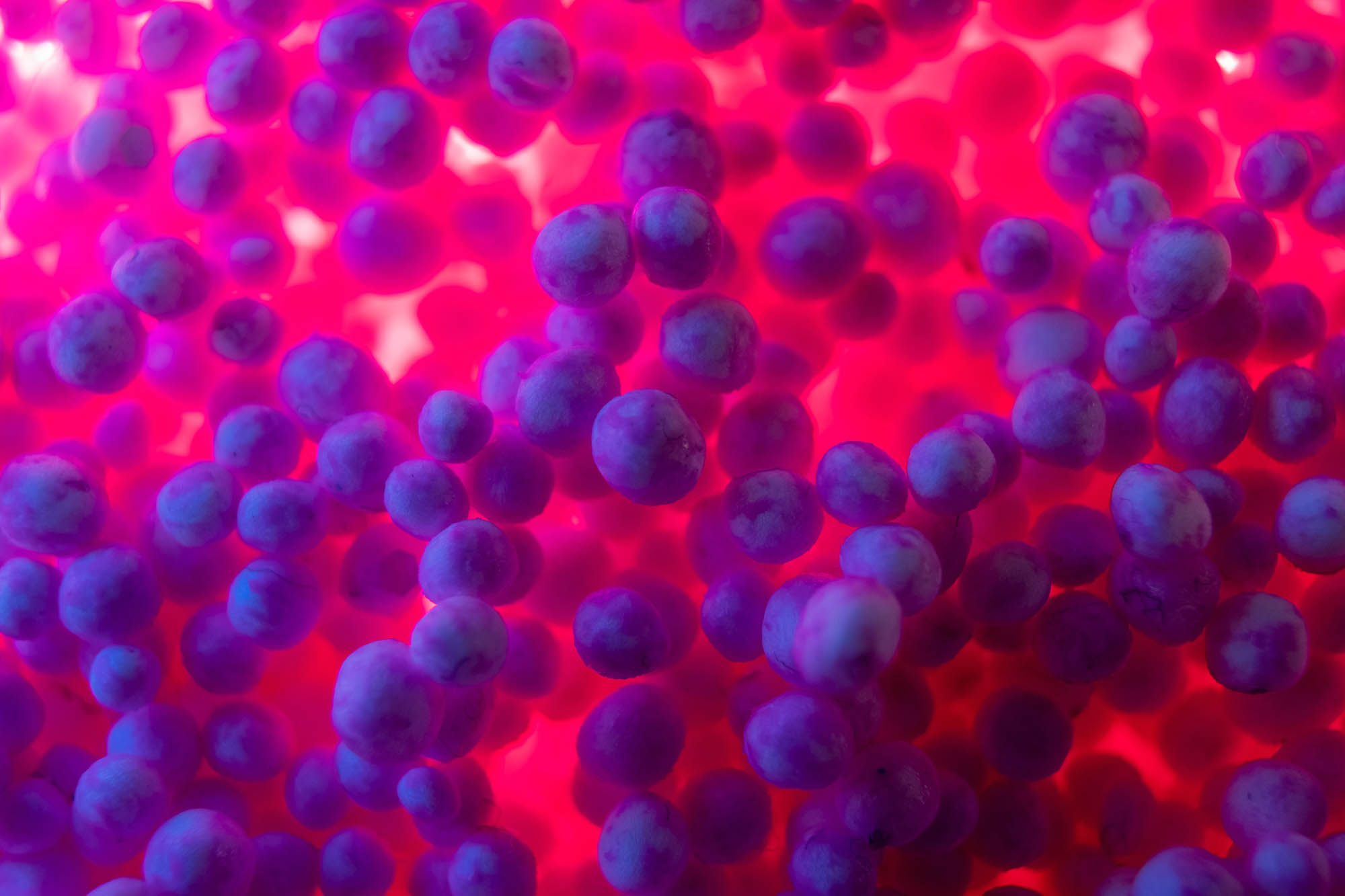

Far from foam.

How problematic is expanded polystyrene, the scientific name for what most of us know as Styrofoam? Let us count the ways.

One: It’s synthetic. All those food trays, coffee cups, and funny peanut-shaped packaging kernels we use require a whole bunch of fossil fuels to produce, along with a fair bit of hydrochlorofluorocarbons, chemicals responsible for punching a hole in the

ozone layer.

Two: We’re stuck with it. Styrofoam can take over 500 years to decompose, leaching a toxic brew of carcinogens all the while.

Three: It’s nearly impossible to recycle. Even in communities where it can be put in the blue bin, any contamination (say, from food or dirt) makes it unusable. As a result, most of it ends up in the landfill. In fact, some estimates suggest Styrofoam accounts for up to 30 per cent of everything buried in the world’s dumps.

Four: It can break down into microparticles that can fly to the ends of the Earth and poison almost every part of our food chain. All in all, there are more than enough reasons to stop using the stuff.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) may have figured out how to help us do that. Partnering with the Wet’suwet’en First Nation in B.C.’s Interior, the scientists have created a new “biofoam” that replaces the long-life synthetic fibres with natural ones from waste wood. Mixed with foaming agents and baked at 80°C for a couple of hours, biofoam is a little darker than its better-known counterpart, but its texture and density are similar, and it can be bent, twisted, and moulded just the same. Like Styrofoam, it’s a great thermal insulator (insulation is one of Styrofoam’s main uses), but unlike the synthetic stuff, the natural fibres decompose in soil in about two months. Production costs are a fraction of the retail price of Styrofoam, giving manufacturers, shippers, and forestry companies plenty of reasons to make the switch.

Best of all, the wood fibre that goes into biofoam is sourced in part from trees killed by the forest pine beetle epidemic of the early 2000s, a blight that destroyed an incredible 731 million cubic metres of marketable pine in British Columbia. In this, biofoam could end up removing a big source of wildfire fuel from the forest—a serious and increasing problem in Wet’suwet’en territory—while recapturing economic value formerly thought lost.

More than enough reasons to make the switch. Not that we’re counting.