-

The PH1 home, a Wernerfield project, in Preston Hollow, Dallas. Photo by Charles Smith.

-

The main living room houses furnishings by Joe D’Urso for Knoll, Tom Dixon, Mario Bellini for Cassina, Jean Prouvé, and Vincent Van Duysen for B&B Italia. Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

In the family room, a 1970s Richard Young cabinet. Photo by Robert Yu.

-

The exterior of the home was constructed with white stucco and dry-stacked limestone cut from a quarry in Granbury, Texas. Photo by Charles Smith.

-

A vintage teak secretary designed by Peter Hvidt in the entry is accessorized with various vintage collectibles, including a rare painted wood sculpture by C. Jeré. Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

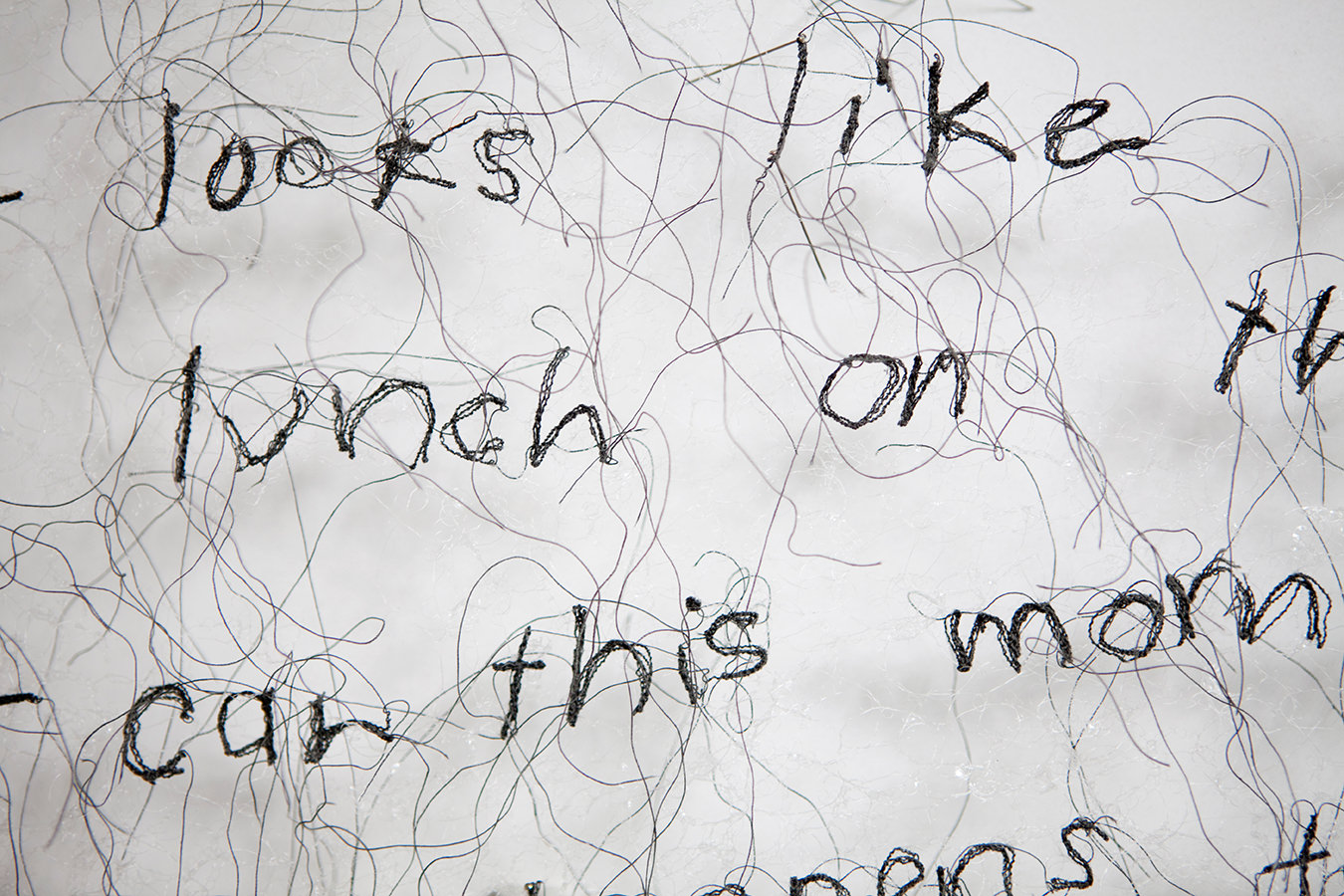

Rebecca Carter’s threaded wall sculpture It happens to all of us (for the stranger). Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

A pair of vintage leather and rosewood 925 chairs by Afra and Tobia Scarpa flank a glazed ceramic side table, with a vintage Arredoluce Triennale floor lamp by Gino Sarfatti behind. Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

Antique Japanese pottery atop of a pair of Hexagon tables designed by Steven Holl. A lounge chair by Vincent Van Duysen sits in the background. Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

The PH1 project features a custom Poliform/Varenna kitchen. A custom reclaimed wood and steel dining table (designed by the architects) sits behind a rare vintage sofa designed by Joseph D’Urso for Knoll in the early 1980s. Photo by Justin Clemens.

-

The living room features a trio of oak and brass Cleat boxes designed by Commune, a Flexform sofa, a vintage Long John bench designed by Edward Wormley for Dunbar, and a set of rare bronze and leather Knoll Brno chairs. Photo by Robert Yu.

-

A pair of sterling silver Polygon vases, designed by Tobia Scarpa for San Lorenzo. Photo by Robert Yu.

-

The intent of the master bedroom was to keep the room serene. The muted colours of the dark wood door and floating side table complement the reclaimed wood siding. Photo by Robert Yu.

PH1 Project Dallas

Mid-century classic.

There are several morals to the story of PH1, a residential project in the Preston Hollow neighbourhood of Dallas, Texas. First, it is a story about the vitality of modern design in Texas and a story about how successful design can be when architects and interior designers work closely together—the warp and the weft of a single fabric. It is also a story about how to connect contemporary and modern design so that not every marriage need crumble under the weight of home renovation and, not least, a story about how complex and rich minimalism can be.

PH1’s mid-century modern–inflected architecture was designed by Dallas firm Wernerfield, while the interiors, by Joshua Rice, also a local, were carefully curated and cleanly composed without looking starchy or uninviting. Initially, Wernerfield was commissioned to remodel a sixties Texas ranchburger-style home, but it was later decided that a new build in the same spirit (situated on a different part of the one-acre lot, away from the street with better views onto a pond) would yield better results.

Certain elements of the new 4,800-square-foot single-storey home were incorporated expressly to bridge the divergent tastes of the clients: while the husband liked modern design, the wife preferred a more traditional look. By using reclaimed wood and exposing ceiling beams, the architects “softened the palette” of the house. Corten steel and dry-stacked stone also helped to reconcile the couple’s sensibilities, lending a rustic character that is both up-to-date and warm.

Privacy was important to the clients, but they also wanted plenty of glass, light, and views, so the architects used the stone walls, a window cut very low into the dining room wall, and a C-shaped courtyard to maintain views from all parts of the house while blocking those from the street. “We always try to create a strong connection between the interior and exterior,” architect Paul Field explains. “The challenge with this transparency is to have large expanses of glass without the homeowner feeling as though they are living in a fishbowl.”

Field hails from Peterborough, Ontario, and earned his architectural degree in Ottawa in 1999 before moving to Dallas to work with local architect Gary Cunningham in 2000. He met his future business partner, Dallas native Braxton Werner, in Cunningham’s office and by 2006 they had struck out on their own. “Dallas has changed tremendously in the last 14 years,” Field says. “It has a reputation of being very conservative as far as politics and most fashion and design goes, yet it has had a strong tradition of modern architecture since the fifties.” Native Texan architects such as O’Neil Ford were pioneers of the modern movement, and during the seventies and eighties icons like I. M. Pei and Philip Johnson built important large-scale projects there. Since then, modern design has continued to grow in popularity. To wit: the recent completion of the massive Dallas Arts District and urban park development, which includes buildings by Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas, and Allied Works Architecture. There is even a bridge over the Trinity River by the poet of water-span engineering, Santiago Calatrava.

Rice, who grew up in Oklahoma and studied interior design in Texas, helped with the renovation of some of the area’s many modernist houses (designed by the likes of Edward Durell Stone, Edward Larrabee Barnes, Richard Meier, and others) after joining the Dallas firm Bodron + Fruit in 2000 and prior to opening his own practice in 2007. Rice began observing the PH1 architecture during construction and came on board. He says: “I was given carte blanche, keeping in mind that the stylistic preferences of the family were defined during the architecture phase and successfully executed. The interiors and art were just a holistic continuation of these predefined preferences.”

Rice was asked to accommodate only two existing items: the dining table, designed by the architects using the same reclaimed wood and steel that runs through the house, and, above it, the Jurgen Bey Light Shade Shade pendant lamp (which nests a glass chandelier in a mirrored modern shade) for Dutch label Moooi. Rice combined these with vintage Chinese Chairs designed in the 1940s by Hans Wegner and produced by Denmark’s PP Møbler.

“I am a huge fan of minimalism, but as a designer, I’m fully aware that it is a hard sell to most clients,” Rice admits. “It just isn’t practical, especially for a family with children. I do, however, try to use these minimalist leanings as a starting point. I start with the idea of a John Pawson–esque level of minimalism and slowly add to it until I achieve a livable, comfortable balance.”

Rice believes that interiors should complement the architecture (if it has any merit). “This project was a huge relief,” he says, “because it required absolutely no backtracking. There were no spaces that needed to be fixed or adjusted to accommodate a successful, holistic design, and that enabled me to concentrate fully on the interiors and art.”

Rice first developed a “dynamic and logical” furniture plan, while creating a schematic list of furnishings and decorative objects appropriate for each space. When selecting items, he has a punch list of important functional and aesthetic features. Craftsmanship and pedigree are more important than provenance, for example. “I back into the final selection that way,” he explains, “rather than just saying, ‘Oh, I like that chair.’ ”

Rice worked with the clients to elucidate the quality and collectability of the design work, helping them to curate a collection of high-quality, important pieces, much as an art consultant would help a client create an art collection that represents their tastes while being a good investment. In this case, the warm minimalism of the house blended well with the Danish modern style, but “to avoid predictability,” Rice says, he included American and Italian classics as well. In the living room, the Long John bench with bentwood legs was designed in the 1950s by Edward Wormley for Dunbar in the U.S., while the two rosewood and saddle leather chairs, called 925, were designed in the 1960s by Tobia and Afra Scarpa for Italian furniture label Cassina. Gino Sarfatti made the 1950s Italian brass lamp, Triennale, for Arredoluce. In a single room, he dovetails mid-century European, Scandinavian, and American pieces with anonymous vintage finds and up-to-the-moment work by, say, Tom Dixon, Barber Osgerby, or relative youngster Mathias Hahn.

This mix of geographies and periods feels seamless and calm; each piece, in its new context, finds some affinity for the others: “I look all over the world for the things I use,” says Rice, who also looks locally, at mid-century dealers Sputnik Modern and Collage, as well as contemporary dealers Smink and Scott + Cooner. “I am a collector to a fault. I own more pieces of rare furniture and design than I can fit in my home or use in my projects.”

On the art side, Rice opted to draw in as much local talent as possible from sources like the RE Gallery, which represents emerging talent, and the Barry Whistler Gallery, for established talent. In one hallway, there is a thread text by Rebecca Carter. In the living room, a canvas by Lorraine Tady hangs over the fireplace. The architects developed a detail put to good use by the interior designer: they embedded pocket tracks in the walls into which art can be mounted and slid into place. In the living and family rooms, tracked panels of salvaged wood planks hide recessed TVs instead of art. Thing is: the worn old wood looks, for the world, like an artwork itself.