-

Rod Arad.

-

Ron Arad with the varied iterations of his “Big Easy” chair.

-

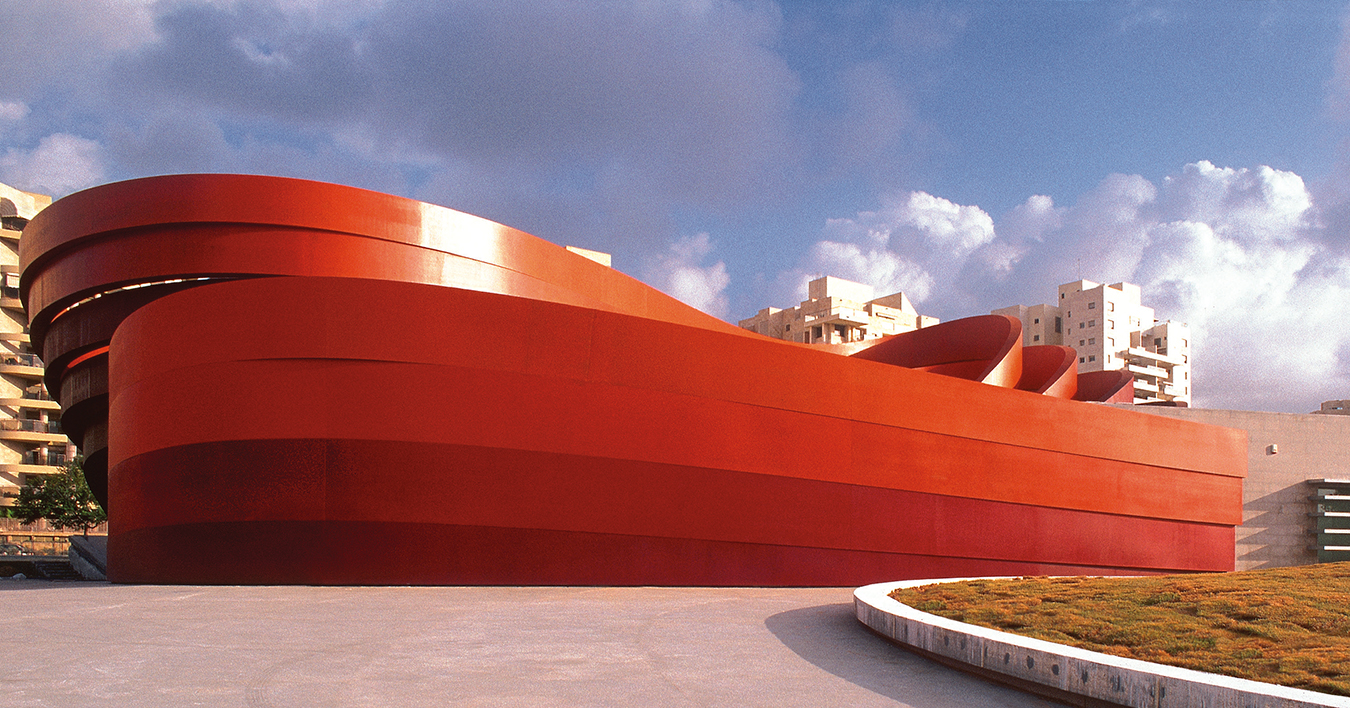

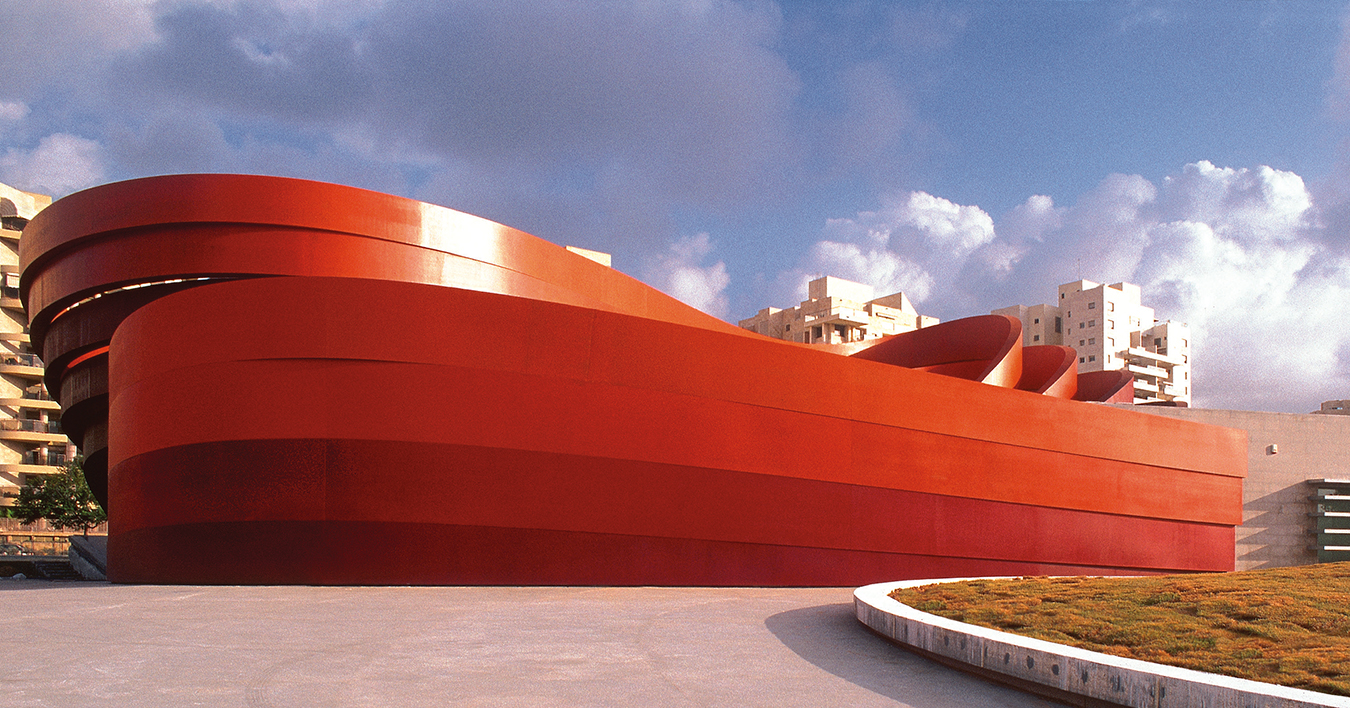

Ron Arad’s Design Museum Holon in Israel. Photo by Yael Pincus.

-

Ron Arad’s Design Museum Holon in Israel. Photo by Yael Pincus.

Ron Arad

Design daredevil.

In the early 1970s, Ron Arad moved to England to attend architecture school. He had previously studied at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, and London, says Arad, “seemed like an exotic place to go to. In contrast to all the Hollywood films I used to watch, whenever you saw a film that came from England, it seemed like culture. As a young person, almost every film that came from England was poetry and literature, especially films like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment. Also, London was nearer where I was than New York—swinging London and the Swinging Sixties.”

The son of a Bulgarian-born mother who was a painter and a Russian-born father who was a sculptor and photographer, Arad studied at the Architectural Association School of Architecture from 1974 to 1979. He describes his admission interview in vintage Ron Arad fashion: cheeky, sly, and fearless. “I joined the queue for the interview … I didn’t have a portfolio,” he explains. “I walked into the room and they asked me, ‘Why do you want to be an architect?’ And I said, ‘I don’t want to be an architect. My mother wants me to be an architect.’ Which was true, because she was worried that I might want to be an artist instead, and an architect is more respectable and safer. ‘Let’s see your portfolio.’ I said, ‘I don’t have one, but I have a pencil here. What do you want me to do?’ I was cocky and stupid.”

Ron Arad’s Design Museum Holon in Israel. Photo by Yael Pincus.

After working—unhappily—for an architectural practice in Hampstead after graduation, Arad went out for lunch one day and never returned. He started a design studio in Covent Garden in 1981, coyly naming it One Off. It was here that he made a sale that put him on the road to design-world stardom.

Arad was inspired by Picasso’s sculpture Head of a Bull, which incorporated a bicycle seat and handlebars, and went to a junkyard to find a car seat to turn into a chair. “I had my criteria: it had to be leather, and it had to be easy to mount on a frame,” he says. “I had the idea to make the frame using Kee Klamps, which are cast-iron fittings that were designed in the 1930s for cowsheds and milking parlours, a scaffolding system to put tubes together. And I found someone to bend tube into semicircle for me. There wasn’t any labour pain for this.”

The designer found abandoned seats from a Rover, a car made by a now-defunct British auto manufacturer, which he recycled into “ready-made” chairs à la Marcel Duchamp. These sat in his Covent Garden studio until “a very nice French guy” whom Arad didn’t recognize knocked on the door and bought six of the Rover chairs. The buyer was none other than designer Jean Paul Gaultier.

Arad calls the purchase a “very, very, very private affair, for his private home” and says that Gaultier “had a nose for what’s to come.” The Rover chair subsequently became hugely popular, and helped establish Arad as a creative force to be reckoned with.

In 1989, Arad moved his architecture and design practice, now called Ron Arad Associates, to a warehouse in Chalk Farm in north London. Today, it employs 20 people—half of them architects, half designers. “Everyone is good at what they’re doing,” says Arad. “We work on, say, 25 projects at a time, and everyone’s concentrating on a project or two. I just run around between the tables, and then take [the projects] to my desk. And there’s a ping-pong table in the courtyard, and people love working there.”

Play is, in fact, central to Arad’s work ethic. “I consider myself very privileged because, ever since I was a little child, I play and I make things, and at a certain time in my life, I started making a living out of it,” he explains. “But it is the same sort of playfulness and the same curiosity to do something that wasn’t done before, or to do something that only I can make.”

This playfulness and curiosity have indeed stimulated Arad’s creativity, inspiring him to work in a wide variety of media on a wide variety of projects; the unbridled nature of his creativity is undoubtedly one reason his recent retrospective was called “No Discipline” (which showed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and at the Centre Pompidou in Paris). “I have a studio that is not an exclusive member of any one discipline—it’s not an architecture studio, it’s not an artist’s studio, it’s not an industrial design studio,” he explains. “It is all of them, with no passport between one place and the other.” The exhibit’s name, he adds, could also describe “my temperament a little bit, because I’m not a very disciplined person.”

“I have a studio that is not an exclusive member of any one discipline—it’s not an architecture studio, it’s not an artist’s studio, it’s not an industrial design studio,” Arad explains. “It is all of them, with no passport between one place and the other.”

Among his many diverse and highly acclaimed projects is “Concrete Stereo” (1983), an iconic early Arad design that consists of a turntable, an amplifier, and speakers embedded in concrete. “For some reason, this was written about as ruinism, post-Holocaust design, all sorts of things that were very far away from my intentions,” he says. “But you can never argue with interpretations, because if someone sees it, it’s there.”

Arad’s move into a new home in London inspired the creation of the “Bookworm” (1993) bookshelves, a system of swirling strips of shelving that has been a best seller for Italian manufacturer Kartell. First devised from leftover sheets of sprung stainless steel, today the shelves are made from injection-molded PVC plastic. “I remember sitting in my empty, new house and I needed some shelves. And I sort of closed one eye, and with my index finger marked like a big S shape on the wall, an imagined S shape,” he recalls.

The “Bookworm” subsequently spawned more bookshelves, including “This Mortal Coil” (1993), a snail-shaped version in tempered steel whose name Arad stole from Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy, and “Oh, the farmer & the cowman should be friends” (2009), a mammoth bookshelf—named after a song from the musical Oklahoma!—made of Corten steel (a material popularized by the sculptor Richard Serra) and stainless steel, and shaped like a map of the United States.

Arad’s “Big Easy” chair, a large, hollow armchair with ballooning arms reminiscent of Mickey Mouse’s ears, was first created in 1988 using welded steel. The design has since been made in many other versions, the newest of which is a pair of stunning stainless steel chairs called “Even the Odd Balls?” (2008–2009) with the shape of 200 balls laser-cut into (or out of) each.

Asked if chairs are his specialty, Arad replies in his typically cryptic, somewhat sarcastic fashion. “I can’t deny that I made a lot of chairs,” he says. “I don’t have any contract with chairs. I did too many of them, and I apologize for that. If someone observes that chairs are my specialty, who am I to contradict?”

Other recent designs include the “PizzaKobra” (2008), a lamp packaged by iGuzzini of Italy in a pizza box, whose metal coil can be twisted into a sinuous, snake-like shape, lit by six LEDs that can be oriented in any direction; and the “Lolita” chandelier (2004), commissioned by Swarovski, which consists of 2,100 crystals and 1,050 white LEDs morphed into a flat, corkscrew-shaped ribbon that contains 31 processors that can display text messages sent to the chandelier’s cell phone number.

His exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) this past autumn contained 140 objects and architectural models along with 60 videos, most of them displayed in a monumental, curving grid of Corten and stainless steel created by Arad. Called “Cage sans Frontières (Cage without Borders)” (2009), the structure was five metres tall and 38.5 metres long, spanning the length of the museum’s International Council Gallery.

“I’m a sixties child—there’s no escaping that,” says the 58-year-old, when asked about his influences. “I grew up in the periphery, I grew up in the Middle East, so things that happened in Greenwich Village, in Piccadilly Circus, have a lot more significance when you’re far away than when you’re right there, and everything is important. Everything that happened until yesterday is a legitimate influence—coming and spending a week in New York influences you. As a young person, I was moved by the work of Marcel Duchamp, and I love Brancusi and Giacometti, I love artists like Tom Friedman. I admire Prouvé, I admire Castiglione.”

Of Duchamp, Arad says, “Almost everything that happens in contemporary art today somehow refers to Duchamp—he was the one not to take anything for granted.” Giacometti is “the opposite of me. He did one thing again and again and again and again and again, and I tend to jump from one thing to another,” he explains. Prouvé, according to Arad, “allowed the beauty of engineering to appear in design like no one else before him,” while he calls Castiglione “an amazing industrial designer.”

A sense of playfulness and curiosity have indeed stimulated Arad’s creativity, inspiring him to work in a wide variety of media on a vast number of projects.

Although Arad currently calls London home, he travels frequently for work. He and his wife, Alma, a psychologist, have two daughters: Dara, a student, and Lail, a singer and songwriter. To unwind, Arad plays ping-pong, reads, listens to music, and plays the guitar.

The new decade might well mark a new professional chapter for the designer. Significantly, Arad has given up his teaching post and department chair at the Royal College of Art in London, where he began teaching furniture design in 1996. In 1997, he combined that course and industrial design into one department of design products, which he ran until last year. “The course deserved to have someone new, someone that wakes up in the morning and thinks about the course. I didn’t—I’m more interested in my own work. Also, I did all the changes I wanted to at the Royal College,” he says.

Ron Arad’s Design Museum Holon in Israel. Photo by Yael Pincus.

This spring, he will have a three-decade retrospective aptly called “Ron Arad: Restless” at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. (A new show will be on display at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2011.) According to the designer, the Barbican exhibit will contain “a lot of the stuff that was on display at MoMA, and some stuff that was done after the MoMA show. Everything will be in movement, including rocking chairs that will rock with some mechanisms. And each gallery will have a screen, 3.5 metres by six metres, with great, big, moving images.”

Typically chameleon-like, Arad has also dipped his toes into the sea of fashion, a somewhat ironic move in light of his sartorial choices. He is known for always wearing a hat and for being casually—some might say too casually—dressed. (In New York during the opening of his MoMA exhibit, his attire often consisted of Crocs, a T-shirt, and what appeared to be pyjama bottoms.) To that end, Arad designed a black unisex wool felt hat called “Cappello”, manufactured by Alessi, in a limited edition in 2000; MoMA reissued it last year in honour of his retrospective.

“Some people have very good hair, some people have very good hats. I wish I belonged to the first group—unfortunately, I belong to the second,” he says, tongue-in-cheek.

This past January marked the opening of Arad’s Design Museum Holon, in the city south of Tel Aviv, in his homeland. His first free-standing public building, the museum has two concrete boxes of galleries that Arad describes as “curator-friendly”; everything is wrapped in ribbons of varying shades of rusting Corten. “The brief I was given was, ‘Can you do us a building that we’ll be very proud to put on a postage stamp?’ ” recalls Arad, speaking recently at the 92nd Street Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association in New York. “Every little city in the world is jealous of Bilbao in Spain—Frank Gehry’s [Guggenheim Museum] really put Bilbao on the map.”

Uncharacteristically modest, Arad admits he turned down the Design Museum Holon’s request to be the subject of its opening exhibit. “I didn’t think it was appropriate that I would do the first show there. For me, the show is the building,” he explains.

Architecture critics and lovers no doubt will soon decide whether Arad’s Holon museum is as revolutionary and influential as Gehry’s building in Bilbao. But it is unlikely that Arad will care, or that critical praise—or pans—will stop him, as he continues to work, and play, with no discipline but with intriguing possibilities.