Apocalypse 101

The guy with the sign reading "The End Is Nigh" just might be right.

“I have very bad news for you. Are you man enough to take it?”

“God, no!” screamed Yossarian. “I’ll go right to pieces.”

—Joseph Heller, Catch-22

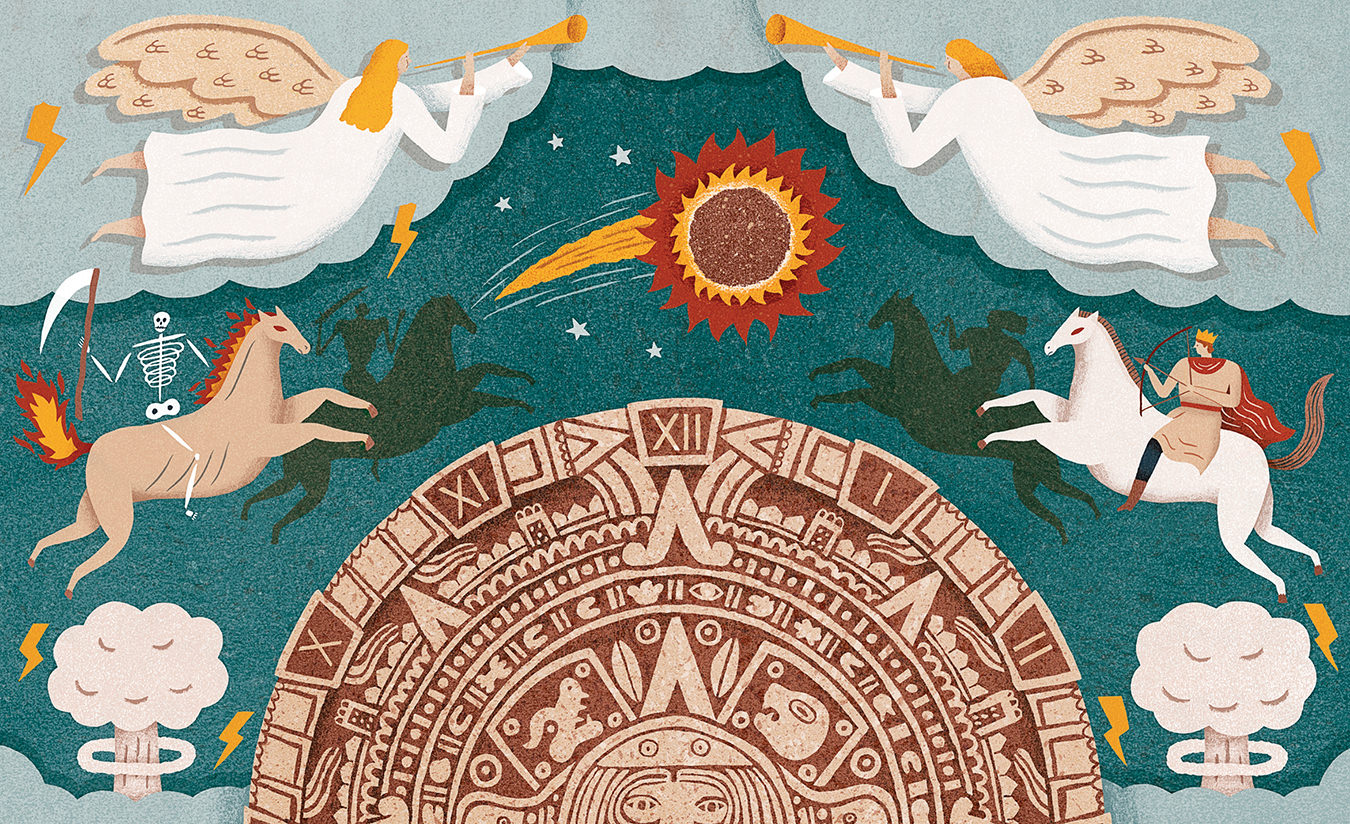

There may be, as the song goes, 50 ways to leave your lover. But it appears there are 100 ways to meet your maker, especially nowadays when hardly a year passes without another troublesome prediction about the end times. Sure, Y2K was a dud, doom-wise. The end of the Mayan calendar passed last December without a single pinata being smashed. And this year’s Atlantic hurricane season will soon be over. But the threat—both real and imagined—of doomsday is the new black. The topic comes up regularly at fashionable cocktail parties and gatherings of pierced and punk bohemians. Decline, drought, dystopia, pandemic, melting ice caps, meteorite impacts, class war, the Second Coming, superstorms, economic chaos… The list is almost endless. Public fascination is insatiable, and the media, following the mentality that “if it bleeds, it leads,” is happy to provide coverage of each prospective threat.

So pick your poison. Dig the tornado shelter. Take the Zoloft. Throw the I Ching. Join the NRA. Turn to a suitable Bible passage. Or, alternatively, don’t. Fear mongering is, after all, a multibillion-dollar industry. Stress sells.

When I was once that little kid living in suburban Boston in the 1950s, I was convinced (as millions of other Americans were) that Senator Joe McCarthy was correct—that the commies had the bomb, and they’d use it unless patriotic Yanks took the threat seriously and uncovered the myriad Russian spies in our midst. Junior FBI agent Danny Wood, age seven, grew suspicious of his next-door neighbours, whose rooftop chimney one day sprouted a then-unfamiliar metal object. A transmitter? An antenna? Something connected to a wire; something ominous. Even more worrisome was the flickering bluish light that framed their closed drapes at night. I was certain they were in communication with Moscow.

In school, we practised “duck and cover” beneath our desks in case an atomic bomb hit. And in our family basement, a big closet served the twin purposes of bomb shelter and storeroom for my gourmet-grocer father’s stock of unsold canned goods. It was here, I suspected, we’d spend our last days, breathing through the keyhole and arguing whether rattlesnake pâté or white asparagus spears would be an appropriate dish for the end of the world.

Hysteria does that.

Shift the scene forward 60 years. Add 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the 2008 economic collapse, the relentless news reporting of mundane mayhem and murder, and voila: a widespread suspicion that the universe is not unfolding as it should. More precisely, a sense that doomsday lies just beyond the next Tim Hortons. And that “duck and cover” is for wimps. When it happens, it’s time to say hello to the preppers. I’m not talking about Hollywood-propelled aficionados of zombie attacks, or those responsible for reporting the nearly 2,000 Canadian sightings of UFOs in 2012 (that’s double the previous year). And I’m not talking about Christian radio personality Harold Camping, who predicted the Rapture would occur on May 21, 2011, and when that date passed, said R-Day was postponed until October 21 that year, and later had to admit he wasn’t exactly sure when it would occur. No, I’m talking about the millions of very real North American disaster preppers who believe that a natural calamity or societal breakdown is imminent, and that stockpiling and arming is the best defence against feral neighbours trying to swipe the five-year supply of Kraft Dinner.

The appearance of the preppers is worrisome because they’re symptomatic of a discontent that is metastasizing across North America and Europe. There must be a reason why the reality TV series Doomsday Preppers is the National Geographic Channel’s most popular show ever. Or why a Canadian survivalist company can market a family pack of emergency food—heavy on powdered eggs and cheese, freeze-dried fruit, and an awful lot of beans—to last a year for $8,669.94. Those on the right look at the rise of the BRICS countries, especially China, and the possibility of Western political instability, and see trouble. Those on the left look at climate change, globalization, and youth unemployment, and see trouble, too. They may both be correct.

In fact, history is replete with announcements of the end times and mass apprehension. Assyrian clay tablets dating to 2800 BC reported, “Bribery and corruption are rampant. Children no longer obey their parents. Every man wants to write a book. The end of the world is approaching…” But nothing happened. In 1501, nine years after discovering America, Christopher Columbus—an ardent believer in the Second Coming—calculated there were 155 years left before the world ended. The year 1656 came and went. And nothing happened. In 1910, as Halley’s Comet approached Earth, hysteria swept Europe after a French astronomer predicted global destruction, and thousands purchased “comet pills” and “canned air” as prophylactics against the comet’s presence. Nothing happened (except some charlatans made a quick profit). In fact, in every one of the numerous predictions—many sources cite 150-odd major ones—of the end times across almost 5,000 years of recorded human history, nothing happened.

History is replete with announcements of the end times and mass apprehension. In fact, in every one of the numerous predictions of the end times across 5,000 years of recorded human history, nothing happened.

Today, however, when a meteor explodes over Russia, or a hurricane heads toward New Jersey, everyone knows about it. Modern 24/7 news and the voyeuristic social media make anxiety much more likely. Millions of people share the vicarious thrill of watching events unfold in real time (not merely reading some obscure Assyrian clay tablets 5,000 years later). Over the course of the Earth’s last half-billion years, there have been five great extinction events during which most of the planet’s creatures abruptly died. The best-known was the impact of a 10-kilometre-wide meteorite into the Yucatán Peninsula 65 million years ago. The explosion, one billion times greater than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, wiped more than half of the world’s species, including the dinosaurs. Today, many scientists agree that we’ve entered a new geologic period, called the Anthropocene, when human-produced calamity may do to the Earth what nature alone has done in the distant past. As CO2 levels rise, dramatic climate change is under way. Oceans are warming and becoming acidified. Species are going extinct. The human population is booming, and consumption is outstripping planetary resources. Under these circumstances, panics and pandemics are increasingly possible.

Add to this equation the spread of global terrorism, serious economic crises among many wealthy nations, a rising worldwide unemployment level, and a suspicion that governments are incapable of halting these trends, and the possibility of doomsday—once limited to atomic warfare—is no longer irrational.

A few weeks ago, I got into a conversation with famed Canadian historian and writer Ronald Wright about how civilizations come to an end. It was the subject of his bestselling, ironically titled 2005 book, A Short History of Progress. He explained to me that, while wandering amid the Guatemalan ruins of the Mayan capital of Tikal, he asked himself: What are the patterns of decline and doom? How is it that the Mayan civilization, which thrived in Central America for over 2,000 years, suddenly ceased to exist during a few decades in the middle of the ninth century AD? Could the forest-enshrouded stone towers at Tikal be a preview of Manhattan or Toronto in 100 years? Throughout history, he told me, the patterns of decline are almost the same. Rome, Sumer, the Maya, Easter Island: each civilization faced an ever-widening gap between a fortified oligarchy and the restive poor, each came to require obedient and expensive military or priestly legions, each depleted its natural resources in end-time frenzies of consumption, each ignored the clear environmental warnings, each tried to forestall trouble with public festivities, and each collapsed amid civil strife. Wright looked at me and said nothing, letting me make the connection between then and now.

In Rome, as the collapse approached, the poor were invited to gladiatorial spectacles within the Colosseum, and received free bread on their departure. The Maya are believed to have publicly sacrificed slaves atop their pyramids, offering still-beating human hearts in order to appease the gods. During the depths of the Dirty Thirties, there was Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers tap dancing, and endurance pole-sitting contests, and running-backward marathons; today there’s Black Friday shopping mayhem at Walmart, reruns of The Real Housewives’ cat fights, and Legends Football League (formerly called Lingerie Football League) games on TV. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

But amid all the possibilities of 21st-century calamity, the planet is about to get a very real and dramatic glimpse of the dangers ahead. If astronomers are correct, appearing in late-November skies this year, and reaching its brightest in early December, will be five-kilometre-wide Comet ISON. First spotted a year ago by Russian scientists, this gigantic snowball—like the thing that wiped out the dinosaurs—is incoming from deep space at over 80,000 kilometres an hour. Experts speculate that it will, fortunately, miss the Earth, but pass very close to the sun, producing a celestial event (if current projections remain accurate) almost unparalleled in human history. Visible during daylight, and possibly brighter than the full moon at night, the comet will serve as an exclamation that we occupy a vulnerable little corner of the universe. Some will feel apprehension. In some places, people will beat pots and pans to drive off the intruder. Others will look for omens, announce prophecies, and inevitably see the comet as a sign of the approaching end times. Some, however, will feel awe and cosmic insignificance. They’ll tell themselves that, statistically, the chance of a mass worldwide extinction by way of meteorite sometime in the 21st century is only about one in a million, and conclude the odds are good. And life will go on. But the comet’s arrival will remind humankind that attention must still be paid. Nothing is certain. The dangers ahead are real. Change, not apocalypse, is in the air.