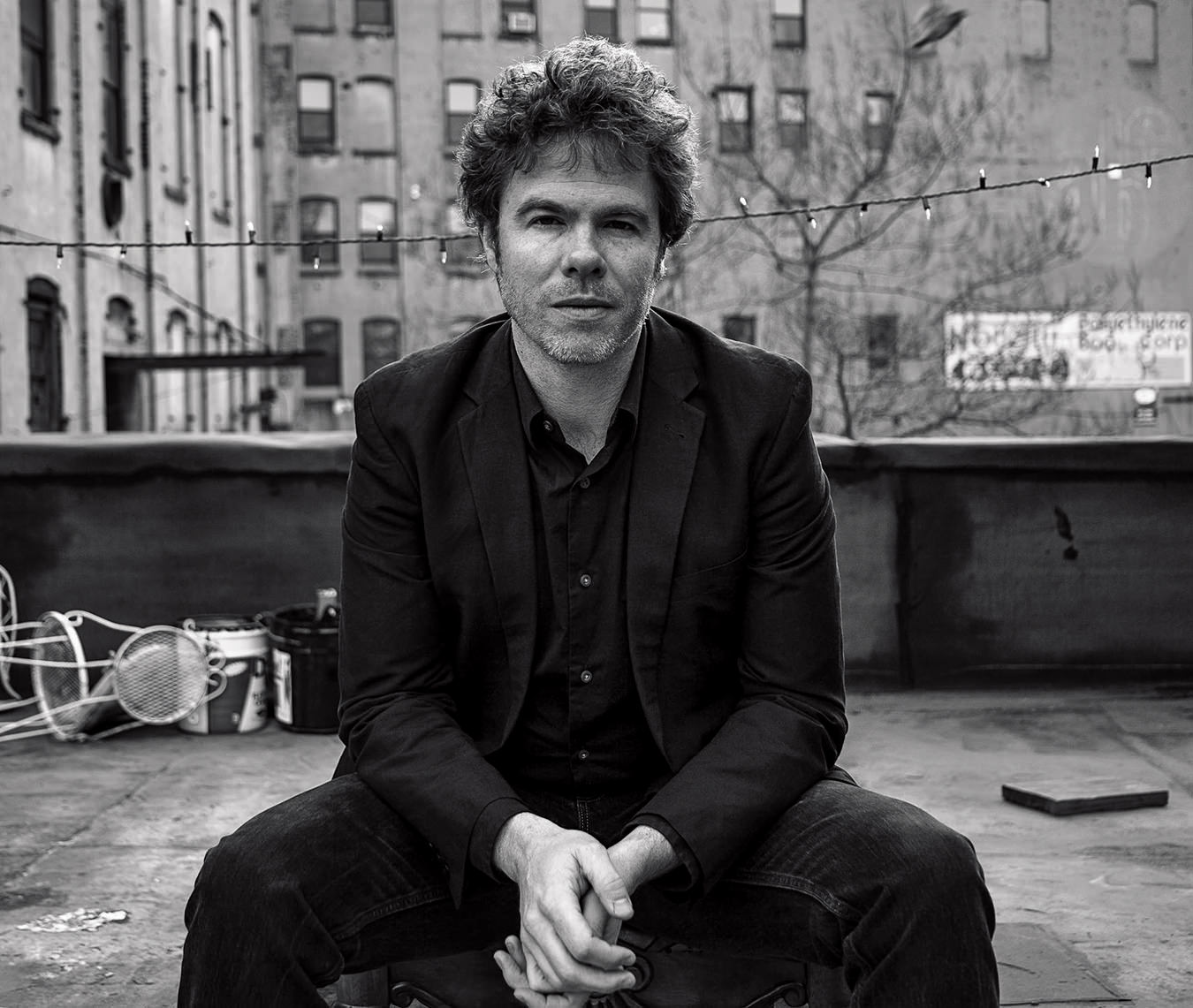

Joseph Shabason Is Happy as Hell

On his latest album, Welcome to Hell, the Toronto musician tackles something new—happiness.

“It’s fucking disgusting out there,” Joseph Shabason says as he closes the door to his studio, a musician’s playhouse littered with instruments in the repurposed garage behind his Toronto home. It’s an uncharacteristically hot September day, and the raucous din of cicadas, broken up only by the small sounds of Shabason’s wife and children, is audible even after the door shuts behind him. After pouring two much-needed glasses of water and sitting down by his computer, the 41-year-old musician immediately starts playing with his camouflage-patterned Crocs, his busily fidgeting arms cluttered with wounds from recent skateboarding accidents. Although not inhospitable, it’s apparent he would rather be working on his music. Shabason has ADHD, and his self-proclaimed workaholism—evident in his prolific musical output—is one of the outlets through which he is able to channel his abundant energy.

When he was growing up in Bolton, Ontario, a town of just over 25,000 located 45 minutes northwest of Toronto, Shabason’s childhood was informed by his parents’ artistic proclivities. His father, an accomplished jazz pianist, and his mother, a visual artist whose medium switched from ceramics to papier mâché to painting, instilled in the adolescent Shabason a love for the arts, music especially. Eventually, he left Bolton to study jazz performance at the University of Toronto. When there, he immersed himself in the oft-competing worlds of the big city’s various underground scenes and the rigorous academics of his jazz studies, and eventually became disillusioned with the latter’s dogmatic approach to composition. After graduating, apart from some gigs and menial commercial work to pay the bills, Shabason more or less abandoned the saxophone for a spell.

Like many of today’s most talented jazz and ambient musicians, Shabason is far from a household name. But between featuring on albums by, and touring with, the Dan Bejar–led Vancouver art-rock outfit Destroyer, and spots on albums by The War on Drugs, Austra, and Born Ruffians, among many others, there stands a good chance you’ve heard him play without knowing it. Along with when he gleefully shows off his Akai EWI4000S, an electronic wind instrument/midi controller, Shabason becomes most animated when discussing his musical collaborators.

Shabason nearly jumps out of his seat when his friend and frequent collaborator, Vancouver-musician Nicholas Krgovich, is brought up, but he then instead begins to thoughtfully dissect how their styles complement each other’s. “Recording with Nick is such a trip, because he approaches music from a way different place. The way he thinks about music is way different from me. He can seem easy breezy, which he is. But also, he’s fucking ruthless when it comes to editing. He’s always right. There’s been maybe a couple of times where I’ve pushed back, but for the most part he’s always right.” And while talking about André Ethier, his partner in the band Fresh Pepper, Shabason grins and points to the back wall of the studio, where Ethier’s paintings, many of which serve as cover art for Shabason’s albums, provide a hint of colour to the space’s otherwise muted palette.

Shabason’s recording studio is in a former garage behind his Toronto home.

It was on Destroyer’s 2011 Polaris Music Prize–shortlisted Kaputt that Shabason rediscovered his groove on the sax, and where he started making a name for himself with his free-flowing, throwback style. As with many of his collaborations, Shabason’s involvement on Kaputt—which eventually extended into recording saxophone, flute, and effects parts for Destroyer’s two following albums, 2015’s Poison Season and 2017’s Ken—began as a purely social relationship. While visiting his then-girlfriend, now-wife, in Vancouver when she was studying journalism at the University of British Columbia, Shabason decided to reach out to Bejar to see if he wanted to hang out and play some music casually. The result of the relationship was no more than some of the most acclaimed and memorable saxophone parts of recent memory, relaxed stylings that are almost imperceptible throughout Shabason’s solo catalogue.

On his 2017 full-length debut, Aytche (pronounced like the letter h), Shabason’s tranquil ambient melodies are contrasted against manic, arrhythmic synths on “Smokestack” and, jarringly, an archival BBC recording of a man describing his Holocaust survivor father’s wartime experiences and eventual suicide on “Westmeath.” On Anne, named for Shabason’s mother, steady, bell-heavy soundscapes and sparse saxophone riffs are overlaid with candid discussions between mother and son about intergenerational trauma and her Parkinson’s diagnosis. And on The Fellowship, Shabason—who is culturally and ethnically Jewish but was also raised in “the fellowship,” an esoteric Muslim group led by Sufi sheik Bawa Muhaiyaddeen—tracks his disenchantment with and eventual parting from organized religion over seven unsettlingly discordant songs before a well-harmonized breath of fresh air comes on the album’s closer, “So Long.”

Between going to synagogue on Saturdays and attending Muslim fellowship prayer meetings on Sundays, Shabason developed a singular relationship with religion during childhood. It provided him with twofold answers for ethical questions, two perspectives on life’s meaning and salvation, and most importantly, a large like-minded community, something he found sorely lacking in the period immediately following his double apostasy. Since then, Shabason has found comfort in, and in some ways fulfilled the role of religion through, his sizable musical community. “When the floor fell out from under me with religion, and I was unbelievably lost in terms of having a true-north moral compass to fall back on and live my life by, what was left, what never changed, was my musical community,” he says. “As I became more confident in who I was without religion, who I wanted to be and what was important to me going forward, I think that, purely subconsciously, my community of friends became truly everything to me. I wouldn’t say it’s a direct replacement or correction from religion, but I would say they filled that void completely.”

If his musical community is the way Shabason found direction after abandoning religion, then skateboarding is how he explored those alternative forms of community while still in it. Along with music, skateboarding informed much of who Shabason is today, and he still skates at parks throughout Toronto a few times a week.

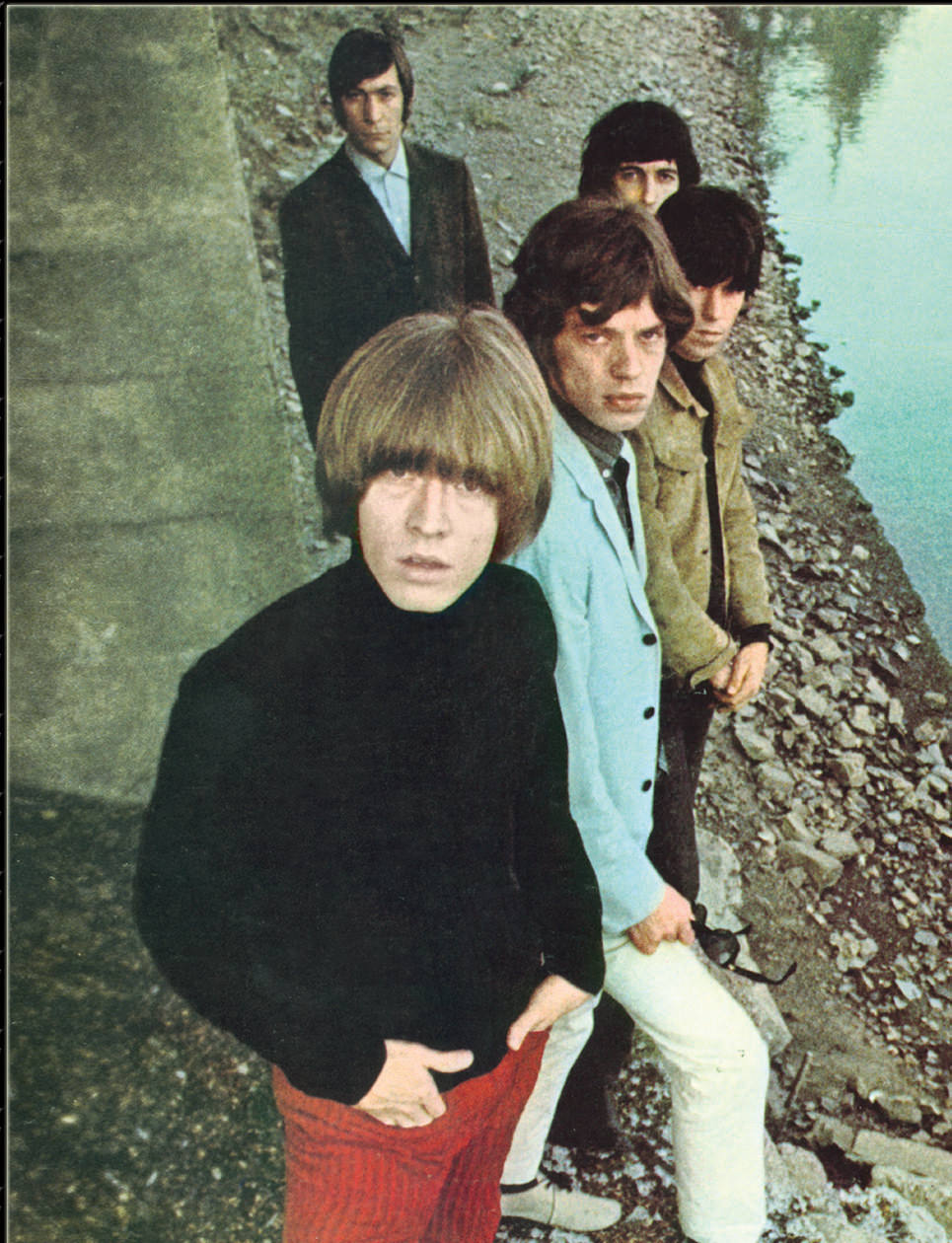

On his newest album, Welcome to Hell, the unexpectedly joyous project released last month via Western Vinyl, Shabason veers from abstract explorations of his deeply personal problems in favour of something more conceptual, a reinterpretation of the soundtrack of the seminal 1996 video put out by the skateboard brand Toy Machine, also titled Welcome to Hell. The 10-track record marks a stark departure from his previous work both philosophically and technically. Whereas on his first three albums Shabason explored his trauma via unnerving ambient melodies (not dissimilar from the ethereal horror of Angelo Badalamenti’s compositions for David Lynch’s Twin Peaks) on Welcome to Hell, joyous choral arrangements glide across funky bass lines, hi-hats, and saxophone riffs that sound and feel like a majorly abstracted score from a 1980s or early ’90s sitcom.

“When I first started this record in my mind, what I thought it was going to be was me and a trumpet player playing these big, long, through-composed melodies. I started doing it, and it just sounded like shit,” Shabason says of his initial attempts. “I was so certain that was going to be the sound, and as soon as I started doing it I was like ‘no, this is not right.’ Then it became about experimenting with different ensemble sounds that would do the compositions justice.” Recording with upward of nine musicians at one time, Welcome to Hell was both challenging and freeing for Shabason. “Before, it was all about being economical, what’s the least you can do to convey the song and give it space. And with this, I was still approaching it with a bit of that mindset. But I also wanted there to be a bit of bombast, because these skate parts are so aggressive and iconic in the way that they changed things, and I wanted it to feel like moving forward and forward and forward.”

Welcome to Hell is the first album where Shabason has unabashedly celebrated the levity of his youth. “I was ready to do something more fun,” he says. “I think that I recognized that my other albums had been kind of heavy, and I wanted something that was markedly different from what I had done. So to lean into something that was a bit more jazzy for me felt really fun, because, you know, I grew up playing that music. And as soon as we starting playing to picture, I said, ‘yeah, this feels right.’”

___

“I wanted something that was markedly different from what I had done. So to lean into something that was a bit more jazzy for me felt really fun.” —Joseph Shabason

Sitting in Shabason’s studio, it’s easy to imagine what the space looked like as he was recording, the former one-car garage filled with his friends and collaborators, Welcome to Hell’s grinds, jumps, and crashes playing on the projector on the wall behind his computer. All around us, the sounds of what is most important to Shabason—music, friends, skateboarding, his wife, and children—reverberate a joy that is palpable on Welcome to Hell. As Shabason opens the door to walk me out of the studio, a wall of hot air and insect song hits us, breaking the magical, hermetic seal where the music is made. Turning to me as he leads the way through his backyard, he grins from ear to ear and remarks, “Jesus Christ, it’s fucking disgusting out here.”