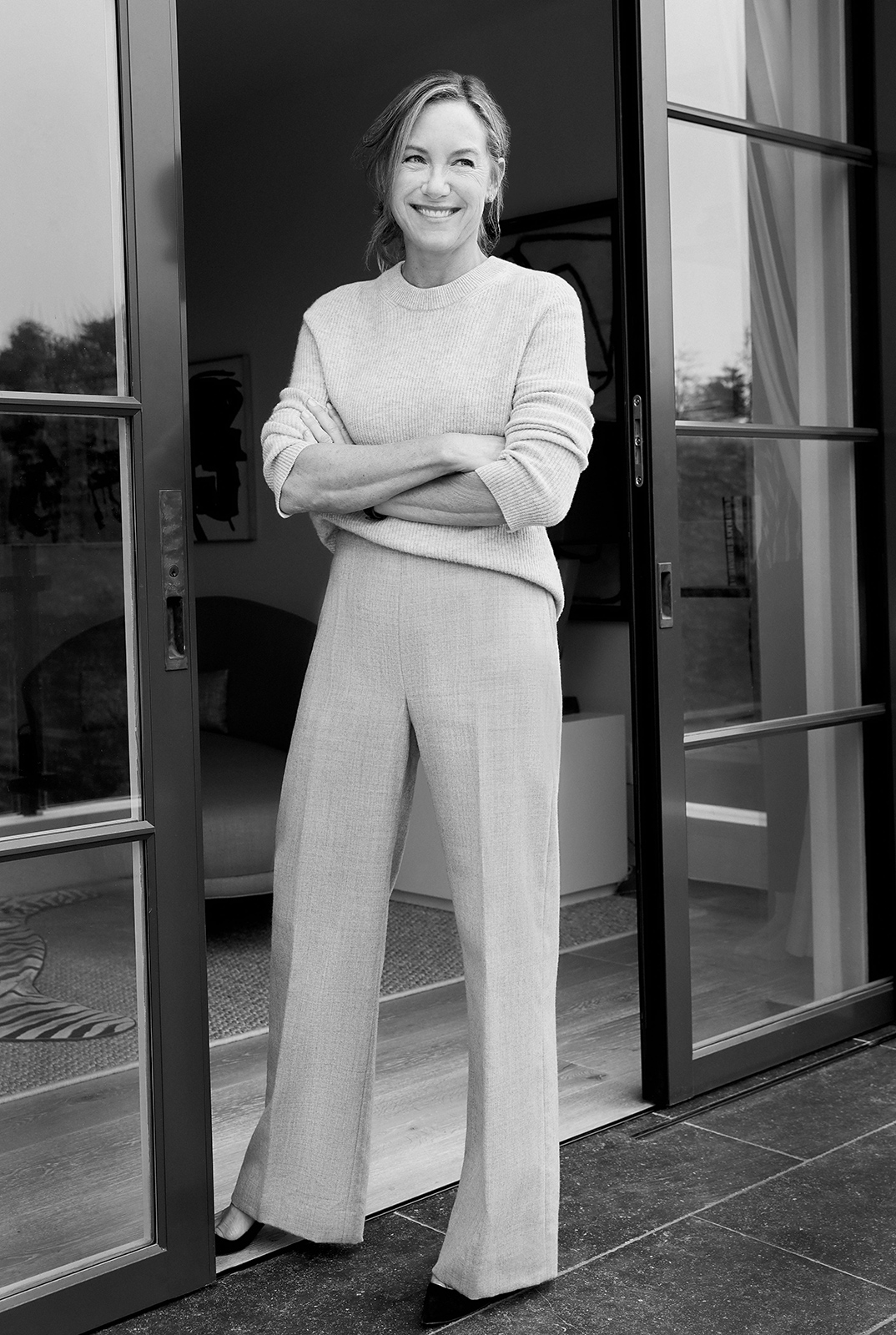

What Comes after Phyllis Ellis’s Documentary Toxic Beauty?

Personal reconciliation.

One tap of a makeup brush, and an amorphous cloud blooms in the air, as gentle as powdered sugar and just as unassuming. We breathe it in, apply it to our skin, let it sit, and move on with our lives, leaving it forgotten. But the body remembers.

The products that we use every day are like ghosts on our skin, and we don’t become aware of their potentially dangerous presence until it may be too late. The delayed reaction makes it near impossible to conclusively and legislatively link beauty and personal care to such health issues as cancer, mesothelioma, or estrogenic diseases, but recent (and not so recent) science suggests that the connection exists. There are many working behind the curtain trying to blow the whistle over the din of the beauty industry’s bright lights and loud voice to show us this link exists.

“Makeup sounds frivolous,” says Phyllis Ellis, a filmmaker, producer, writer, and director of the award-winning documentary Toxic Beauty (2019)—a film that calls into question all previously held beliefs surrounding personal care—and one of the personalities who has successfully cut through the noise. “It seems like it’s outside of what people should take seriously. But when you think about the number of products women are using just to get out the door, it’s significant.” Cosmetics is a $532-billion U.S. industry and is only increasing. The chemicals that enter our body via the use and application of beauty products are flushed by our liver; repeated use of multiple products builds up levels of toxicity in the system that, over time, can lead to serious health concerns.

Chemicals such as parabens (a class of preservatives), phthalates (plasticizers commonly found in fragrances), and other endocrine disruptors are lurking in beauty products. Simon Fraser University (SFU) health sciences professor Dr. Bruce Lanphear and one of the experts interviewed in Toxic Beauty expounds, “despite the fact that we regulate toxic chemicals as though there are safe levels or thresholds, we know that that’s not true.”

The documentary is a spark of change, compiling interviews from scientists, lawyers, and victims of beauty product toxicity, woven alongside footage and audio of courtroom and governmental hearings that contextualize the symptoms of a systemic disease.

Ellis’ Toxic Beauty explores how the health of generations of women has been affected by an idolized standard of beauty that involves a regimented use of products that are littered with toxins. “We have to change these beauty norms so women don’t have to choose between their health and trying to look beautiful based on these arbitrary standards that are all about Eurocentric beauty,” Ellis states. The documentary is a spark of change, compiling interviews from scientists, lawyers, and victims of beauty product toxicity, woven alongside footage and audio of courtroom and governmental hearings that contextualize the symptoms of a systemic disease.

The main thrust of the film is the ongoing class action lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson that alleges the company knew its baby powder contained talc, a clay mineral closely associated with asbestos, which allegedly causes ovarian cancer. In 1982 obstetrician and gynecologist Dr. Daniel W. Cramer published the first study that also linked talc to ovarian cancer. The study found that women who dusted their genitals and/or sanitary napkins with talcum powder were three times as likely to develop cancer as women who did not. At the time, Johnson & Johnson publicly criticized the study, calling the findings “inconclusive,” and the battle has ensued with further studies appearing to support Cramer’s claim.

In May 2019 as a direct result of the lawsuits and mounting pressure after the documentary’s release, Johnson & Johnson pulled its baby powder from shelves in North America but continues to maintain there was no wrongdoing on its part. Ellis believes that, while it was a big win, talc needs to be banned outright. She shares that Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder is marketed as halal and women use it when they visit Mecca to help with the heat. In her research, she also learned that women in developing countries wet baby powder and add their own pigment as an affordable makeup. And while Johnson & Johnson baby powder is the most well known example of a product that contains talc, there are 2,000 products in circulation today that contain it—including dry shampoo, eyeshadow, blush, and setting powder.

Women today wear more makeup and use more products than ever before, and the formulations and level of colour pigmentation have evolved at exponential rates, but so have the necessary chemicals to achieve those effects. In the documentary, 26-year-old Boston University medical student Mymy Nguyen tested her body’s toxicity levels after applying her 27 daily products and found her phthalate levels were five times higher and her paraben levels 35 times higher than when she applied no makeup. These toxins can cause rashes and hormonal imbalances, and destroy women’s cells. Nguyen was also diagnosed with a benign breast tumor while shooting the documentary.

Cosmetics are a spectator of culture, an ever-present accoutrement to cultural expression, and separating it from personal identity is a tall order. “I made the movie and I still have makeup on,” shares Ellis. She is open about her insecurities and complicated relationship with personal care because she knows that it isn’t easy to “shift and bend and let it all go.”

But she also argues that it is crucial for us to find a way to move away from our reliance on cosmetics because, even though it is the responsibility of governing bodies to research, test, and regulate products, the vast majority of chemicals used in cosmetics were grandfathered in because they were considered safe before legislation such as the Canadian Environmental Protection Act was introduced. Moreover, by law any ingredients considered “incidental” do not need to be disclosed to the consumer, and banning certain chemicals doesn’t guarantee that cosmetic companies haven’t found alternatives that are more toxic.

The only reliable solution is to reduce and remove, according to Ellis and Lanphear.

In the last decade, the clean beauty movement has taken root, consisting of products made without ingredients shown or suspected to harm health. But even so, the burgeoning arena of products is murky, as natural ones can also be toxic. Metal elements such as lead and mercury—naturally occurring yet known to be harmful—are contained in some products classified as clean beauty. Other natural ingredients such as tea tree oil and lavender have estrogenic properties that can cause precocious puberty in children and increase the risk of breast cancer in women.

Ellis tells the story of a chemist and formulator for a large cosmetics company who told her, “when something smells like roses, it’s not like we have a big vat of roses and people are stomping on the roses to get the rose oil, but it’s a big vat in Jersey filled with chemicals to make something smell like roses. And the reason why they do that is because the chemicals that they use to preserve things smell like such shit. They have to put something that smells nice on top of it in order for us to buy it.” When a beauty advertisement reads “our cleanest ever formula,” that implies that there was a level of metaphoric dirtiness to begin with, and most likely there still is. The only reliable solution is to reduce and remove, according to Ellis and Lanphear. Over the course of developing Toxic Beauty, Ellis uncovered information that she says will make us think differently about companies we trust. “I didn’t have enough time in the film to tell all the stories,” she says, and she is currently working on another film that will continue to challenge our perceptions of beauty.