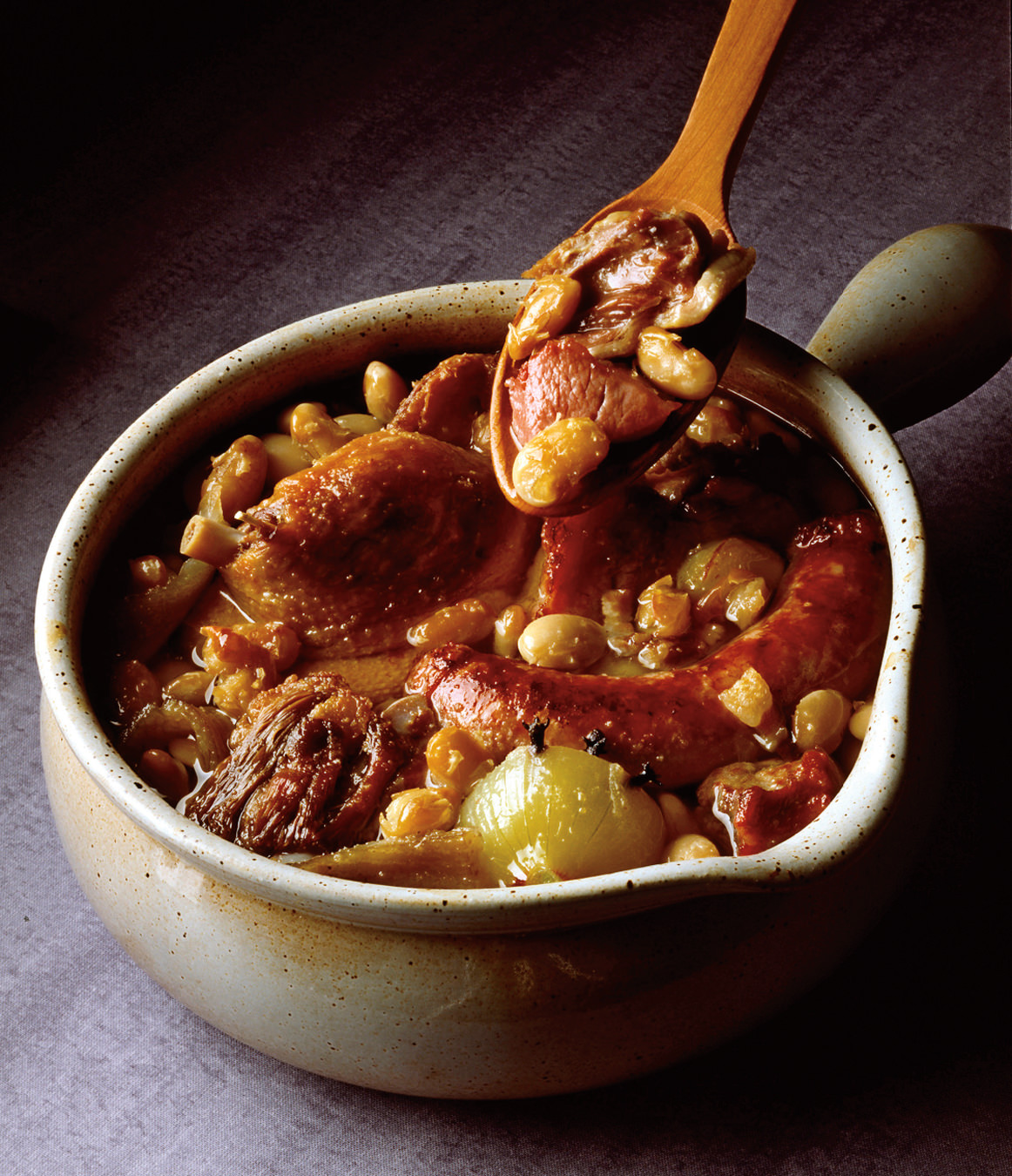

Cassoulet

The hearty, slow-simmered dish.

“We would prefer not to serve cassoulet,” said legendary winemaker Alain Brumont over lunch at his club-like restaurant, La Table de Bouscassé in Madiran, France. “First of all this isn’t the right city for cassoulet. But more importantly, here in the southwest, we are trying to escape the clichés. We are far more interested in serving specialties of the region that are being revived, like caviar by the house Prunier, Noir de Bigorre cured ham, and the famous Tarbais beans.”

I nodded, sipping Brumont’s tannat-based wine, and tried in vain to hide my disappointment at the missing dish. Yes, the caviar was fabulous and the ham was on a par with the renowned Spanish pata negra. But the creamy and velvety-textured Tarbais beans made me long for cassoulet, a cliché, perhaps, but also the signature dish of the French southwest.

Dubbed “the god” of southern French cuisine by none other than chef, author, and gastronome Prosper Montagné, cassoulet is, in its most basic incarnation, a bean stew. And even the choice of beans is up for debate. But the version of cassoulet that made this dish world famous is not simply a bean stew, but a lush ragout of braised beans enriched primarily with duck or goose confit, pork parts, and Toulouse or andouillette sausages. Mutton is common in more northern recipes and the inclusion of gizzards and pork skin points to cassoulet’s humble origins. Cassoulet can have a toasted crumb crust, or not. Some are tinged with tomato, while others are enriched with duck stock, or an alarming amount of pig fat. Don’t be surprised to find pig’s ears, partridge, and/or duck testicles in this, the epitome of French comfort food.

The cities most famous for cassoulet are Toulouse, Carcassonne, and a village by the name of Castelnaudary. No surprise, each location lays claim to the original recipe, though Castelnaudary is generally acknowledged as the birthplace of the dish. Named for the squat clay pot in which it is baked, a cassole, cassoulet can now be found the world over on practically any ambitious bistro menu.

Brumont was right, though. Cassoulet may be ubiquitous in the bistros of North America, but in the southwest of France, from Bordeaux to Toulouse, you’ll find more duck magret and côte de boeuf than cassoulet. When you do find it, depending where you are, the composition can be quite different. And as the rules for cassoulets become looser, the once-small chance of coming across a lousy version has grown a little larger.

As they make up the majority of the dish, beans are the key to a successful cassoulet. A 1966 decree drawn up by the États Généraux de la Gastronomie Française states that a cassoulet should be comprised of 30 per cent pork or other meat, and 70 per cent beans, stock, and seasonings. Ideally the beans should be simmered, holding their shape just until the moment they hit tongue and teeth. As for the taste, long braising in garlic-hued juices ensures their gentle earthiness will be well infused with their surrounding meats and fats.

Cassoulet, a cliché, perhaps, but the signature dish of the French southwest.

The ne plus ultra are Brumont’s beloved Tarbais beans (the same variety grown in California is often known as a “cassoulet bean”), but any large white bean, such as lingot or the larger cannellini, can make for a great cassoulet. A version found in The Cooking of Southwest France, by author and cassoulet expert Paula Wolfert, calls for fava beans, and the person behind that addition is none other than the New York–based French chef André Daguin, whose daughter, Ariane, supplies Americans with the finest meat and cassoulet kits, D’Artagnan.

Cassoulet is best served in cold weather, though I do recall a chef telling me that he and his brother had a ritual of devouring plates of cassoulet in Toulouse each summer, sweating profusely, wearing only their underwear. A French friend used to receive care packages from his mother that contained a dozen cans of William Saurin cassoulet that he cracked open whenever he was homesick.

Canned cassoulet is omnipresent and should not always be shunned. You can find authentic French cassoulet (the best hailing from Castelnaudary) with either pork, duck, or goose confit for about $5 a can at many French gourmet shops. Pop open a half dozen cans, pour into an earthenware pot, cover with toasted breadcrumbs, bake until golden and bubbling, serve with a southwestern French wine and you’ve got yourself a terrific emergency dinner-party feast. Making cassoulet from scratch will take you a full day. And do not expect your first try to be a success. The first time I made one, my beans were undercooked. The second time, my sauce was underseasoned. And the third time, when I finally got it right, my dinner party guests couldn’t manage more than a few spoonfuls. (Be warned: a good cassoulet can wreak havoc on even the best digestive systems, so keep a stash of Pepto-Bismol on hand for the unavoidable goose-fat hangover the next day.) But if the canned version is too gauche and the idea of patiently assembling a cassoulet makes you quiver, consider, perhaps, ordering one from your favourite local bistro. Cassoulet reheats very well and is actually better the day after—or several days after—it is made.

In Quebec, the best cassoulet I have tasted comes not from Montreal or even Quebec City, but farther north, in Jonquière, where chef Daniel Pachon has become the reference for this beloved bean and meat stew. Carcassonne-born, Pachon is the owner of the Auberge Villa Pachon Restaurant, which not only serves a sublime cassoulet but also ships his specialty throughout the province. He recalls his mother and grandmother’s versions containing all the scraps and leftovers in the refrigerator. But for the restaurant, Pachon’s cassoulet is made with pork shoulder, hock, and shank, as well as homemade Toulouse-style sausage and duck confit. As for tomato? Just a touch. Says Pachon: “Cassoulet is a family dish, a dish of the people, and, originally, poor people. It was a nourishing dinner for peasants who worked the fields. Today, we have refined it. It’s not a luxury, yet it is wildly popular—but only when made with love. In the best cassoulets, you can always taste the passion.”

Originally published January 1, 2016.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.

See more of NUVO’s fabled food stories.