Steinway & Sons’ Bespoke Pianos

Play me a memory.

Wiebke Wunstorf listens very carefully. Working in absolute silence, she isolates the strings on a brand-new grand piano using rubber blocks, then strikes the same one or two keys over and over again. She may take a piece of sandpaper and gently abrade the surface of the felt on one of the hammers. Then she starts over, working through all 88 piano keys. With the support of three colleagues, Wunstorf perfects the sound of every single piano that leaves the factory where she works.

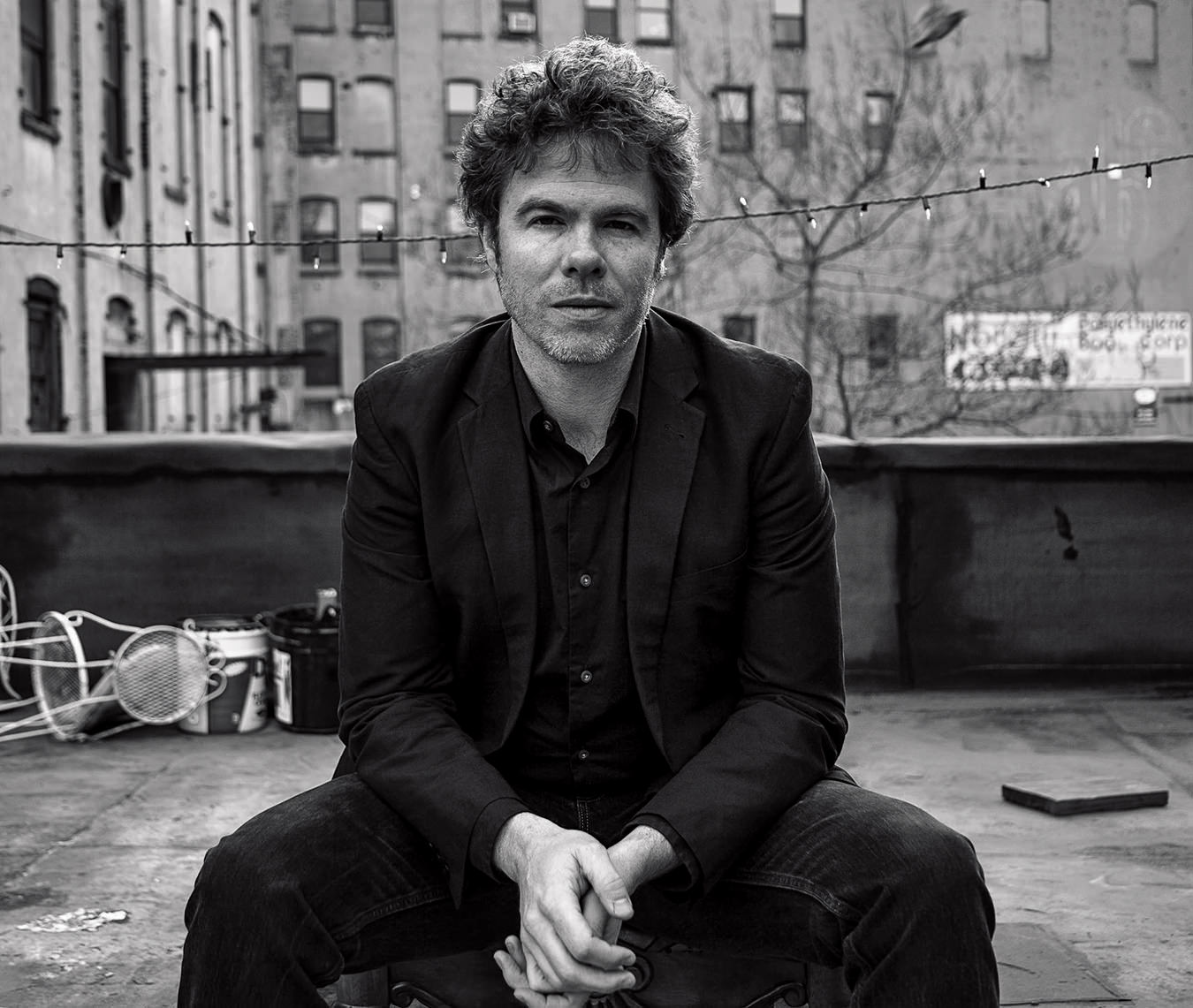

Wunstorf is the “chief voicer” at Steinway & Sons in Hamburg, Germany—maker of what are arguably the finest pianos in the world—and she has worked there for 39 years. Steinway was the piano of choice of Liszt and Rachmaninov, and is the choice of Billy Joel and Randy Newman, not to mention most professional classical players, many of whom insist on having a Steinway shipped to wherever they play. Wunstorf is the one who gives each new piano its distinct “colour”, as she calls it. She speaks of sharpness and cleanliness, fullness and power—and says that achieving this is “an emotional job.”

Wunstorf’s work is also the very last step in a process that involves the hand assembly of some 12,000 parts—case and strings, pedals and hammers, each requiring their own expertise—to produce an instrument that will cost €100,000-plus ($151,000 Canadian). So intricate is the handiwork that only around 3,000 pianos are made each year (the company has factories in New York and Hamburg). “We make tiny changes to perfect the process,” says Guido Zimmermann, president of Steinway & Sons Europe, who joined the company last year after working for pen maker Montblanc, located just down the road from Steinway headquarters in Hamburg. “But the piano is not an easy instrument to evolve.”

Heinrich Steinweg, a German immigrant who founded the company in New York City in 1853 (and changed his named to Steinway while there), discovered that a piano’s sound could be enhanced by using certain kinds of wood for each of its components: close-grained Sitka spruce is used for the soundboards, strong maple and mahogany for the rims, and whitewood for the top and music desk. Only half of the wood the company buys, which is left to mature for two years, is deemed good enough to be used in a piano. The company opened up a European factory and offices in Germany in 1880, and would eventually gain nearly 130 patents. Today, the only truly secret part of the process is the construction of the diaphragmatic soundboard, the sonic heart of the instrument. “It’s incredible that the manufacturing process has been largely unchanged for a century,” says Zimmermann.

However, the time for change arrived in the form of Spirio, the brand’s high-resolution player piano, which launched in 2015 after a decade of development. Spirio has turned Steinway, at least in part, into a tech company. Self-playing pianos have been around for over 100 years, but Steinway’s is considered the world’s most advanced player piano, with a library (wireless connection via tablet) that is 3,000 recordings strong—and growing. The system’s software—developed by an American company, which Steinway acquired—has analyzed and recreated the performances of some of the instrument’s masters, from Vladimir Horowitz to Thelonious Monk and Art Tatum. “So,” Zimmermann says, “you can have the greatest pianists playing almost live in your living room.”

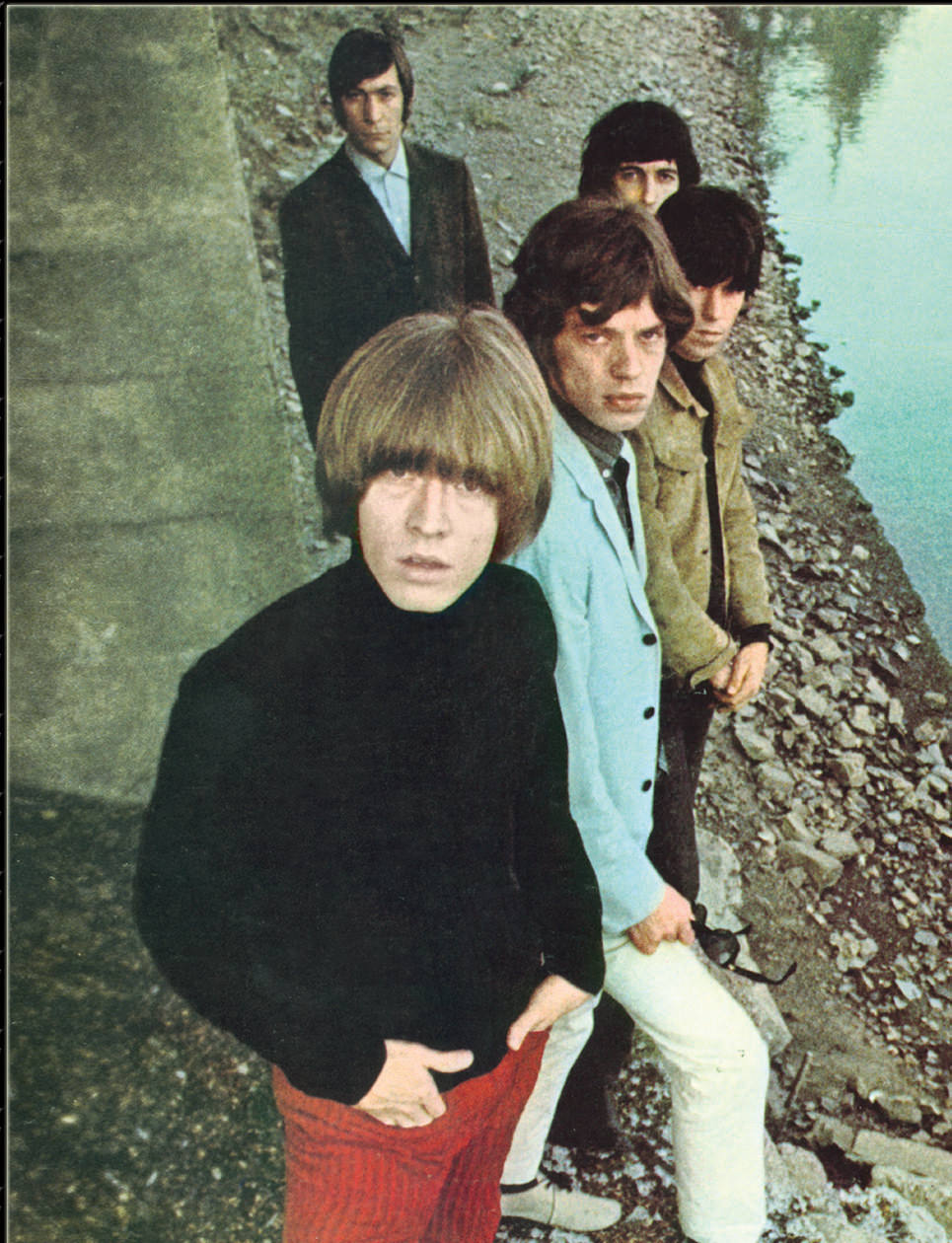

“The piano is every bit an instrument of pop and rock. Pianos belong at home as much as they do in a concert hall.”

Some Steinways are bought by people who have no intention of tickling the ivories—(ivory is no longer used for the keys; instead, a special resin first developed by the company is used). Some buy a Steinway for status, others as an investment. (On the secondary market, Steinways in good condition can be sold for 25 per cent more than the purchase price.) The company was caught somewhat off-guard by demand for Spirio: almost half of its sales are now for the player piano, and demand may increase when new features for pro players are introduced next year.

“There are lots of people out there with the means to buy a Steinway, but who see it as not fitting their needs, because they see it as a piano only for serious pianists,” explains Zimmermann. “As a company, we could survive selling just to professional classical players, especially since the piano market is increasingly splitting into two: entry-level products, which are often electronic now, and the very top end, supplying professionals. But we’d be missing a huge opportunity. The piano is every bit an instrument of pop and rock. Pianos belong at home as much as they do in a concert hall.”

Earlier this year, the company launched its first Sunburst edition piano, in which the standard “piano black” lacquer is given a glowing orange effect akin to that found on the electric guitar of the same name. Future plans include setting up pop-ups and launching Steinway jazz and rock festivals globally that support young, non-classical players. These could be boom times for the piano as an instrument, as much as for Steinway as a brand. Last year, the company created a subsidiary in China to cater to what can only be described as an obsession in that country with the piano, in part down to the celebrity status of Lang Lang and Yuja Wang. There are presently an estimated 40 million piano students in China.

“But we can’t rush,” warns Zimmermann. “There are only so many pianos we can make and we can only increase capacity very slowly, not least because of the challenge of finding and training the craftspeople. A piano technician is a very rare species. When I joined the company, I looked at the manufacturing here and I thought, ‘My God, can’t all this be realized in a more modern way?’ Well, I’ve spent 18 months studying it now, and the answer is no. The feeling the craftspeople bring to the pianos really matters. You can hear it when you play.” He adds, “It’s not a very rational thing for an engineer to say, I know, but it’s all about those positive vibrations.”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.