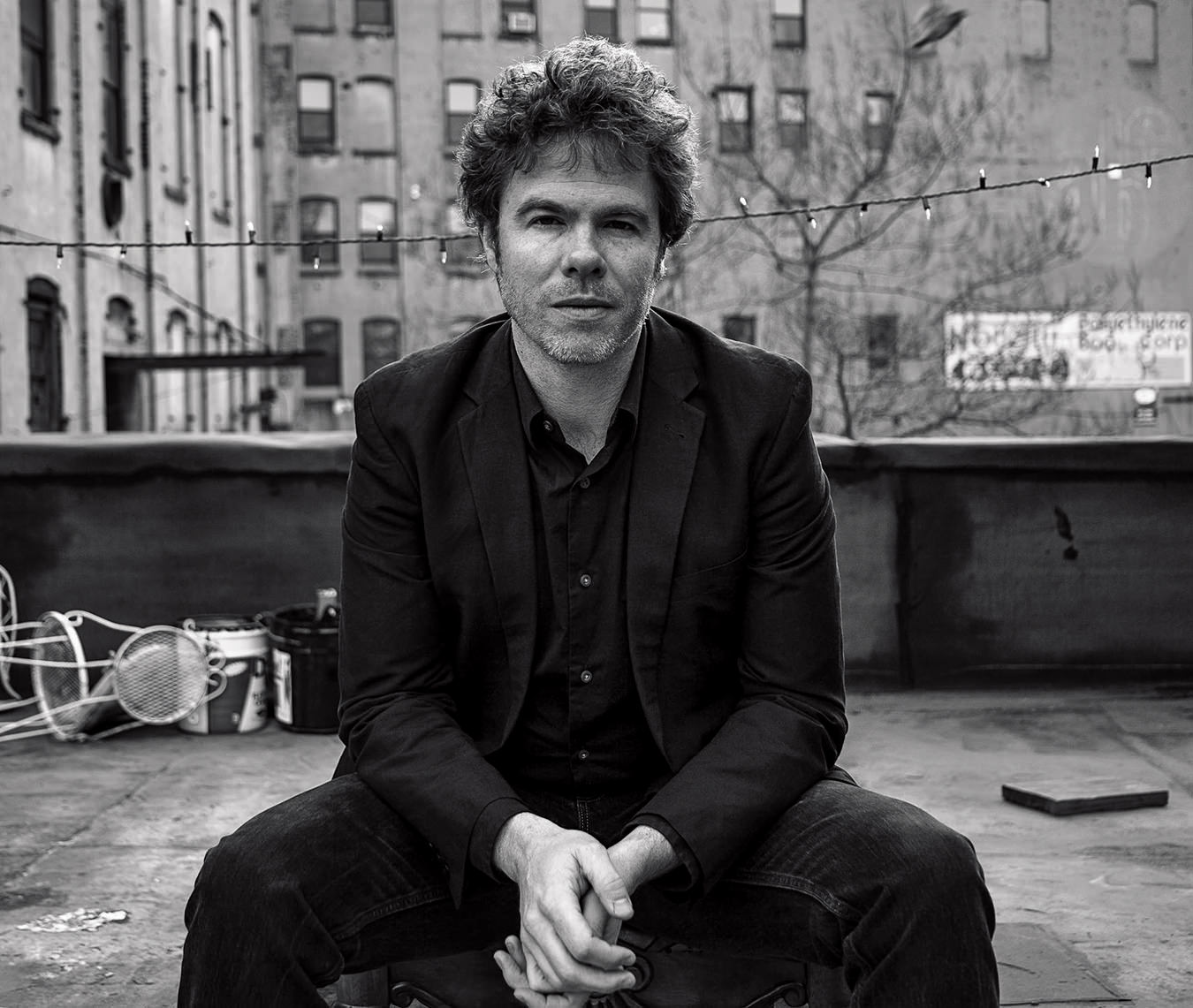

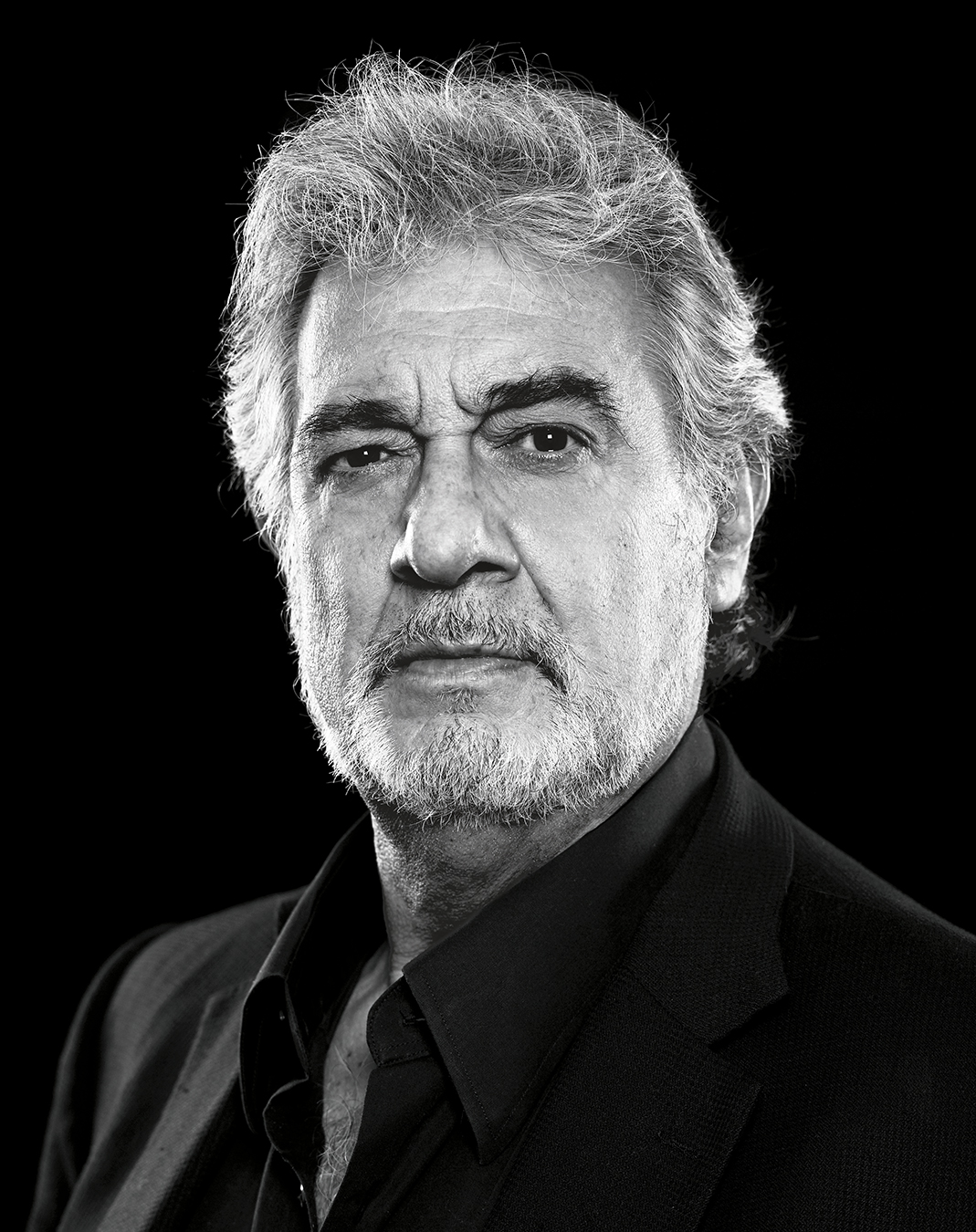

Plácido Domingo

A voice above.

To be one of the greatest opera stars of the day would be enough for most people, but to be simultaneously the world’s reigning tenor, the administrator of two opera companies, and a distinguished conductor, you would have to be Plácido Domingo.

Most singers have a “best-before date” of around 60 years of age, but for Domingo, not the least of his amazing accomplishments is that he continues to dominate the operatic world at the age of 68. As opera houses make contracts for long periods of time, he takes a philosophical view of the future: “Sometimes they take risks with people that simply cancel, or get sick, so they will have to do something if I am not singing.” As to when he himself will decline to make long-term contracts, he gestures vaguely toward his throat and says simply, “I’ll feel it.”

For now, he continues to sing big roles in great theatres. In the current season, he will sing concerts in Mexico and India, and appear in demanding roles such as Parsifal, and Siegmund in Die Wälkure—both heavy parts in works by Wagner. He will also perform the title role in the seldom heard Cyrano de Bergerac by Franco Alfano, and in the hardly more often performed Iphigénie en Tauride, an opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck, Mozart’s great contemporary. He still often sings some of the heroic roles in Italian opera, and two seasons ago he expanded his repertoire with the title role in The First Emperor, the new opera by Chinese composer Tan Dun.

But there is more to being a force on the operatic stage than just singing. Domingo is a compellingly handsome man whose ability to fill out a role makes him as powerful an actor as he is a singer. Musing on one of the characters that he has sung most often, Cavaradossi, the hero of Puccini’s Tosca, Domingo, who knows in his imagination all about Cavaradossi’s pre-opera life, says, “I see him studying painting, being very much involved in politics. At the same time he is a cavaliere, so very much having this kind of presence, a figure, among his family. And then he goes to the painting school, he starts to hear all these political ideas, and he turns into quite a different character.” None of this is explained on stage, but when Cavaradossi/Domingo enters in the first scene of Tosca, he already has a life from which the stage action flows. Neither Cavaradossi nor any other character Domingo portrays is just a two-dimensional stage figure, but someone with a past and a personality.

In the end, though, it is the singing that knocks out the audience. Domingo began his vocal life as a baritone. He is not the only tenor to have done so, but that baritone quality has never left his voice, and it has contributed to the characteristic richness of his sound. The ringing high C is part of his tenor arsenal, but it is not what audiences go to hear, nor is it what distinguishes him. The dark, velvety sound that is so ravishing is what listeners have enthusiastically responded to for more than 40 years.

Plácido Domingo was born in Madrid, Spain, on January 21, 1941. His parents, both singers, were the directors of a zarzuela company. (Zarzuela is a style of popular musical theatre that originated in Spain; although performed in other Spanish-speaking countries, it has not thrived outside of Spain.) The Domingos took their company on a tour of Latin America, and settled in Mexico City, where Plácido and his sister Mari Pepa joined their parents.

In Mexico, Domingo had the kind of jack of all trades experience that proved invaluable for his future career: he sang supporting roles in musicals and operas, sang and conducted with his parents’ troupe, acted on television in small roles and was the pianist-arranger of excerpts from opera, operetta and zarzuela for Mexican television. The future Otello and Parsifal even sang 185 performances, as a baritone, in My Fair Lady.

In 1962, he joined the opera company in Tel Aviv, Israel. The city isn’t one of the world’s great operatic centres, but allowed Domingo to perform major roles away from the international operatic spotlight. Tel Aviv had two other advantages: the baritone Franco Iglesias, and the soprano Marta Ornelas, whom Domingo married. Both Iglesias and Ornelas became the young tenor’s de facto teachers, and he left Tel Aviv a better singer than when he arrived. Marta eventually abandoned singing and developed a career as a stage director of operas.

Most singers have a “best-before date” of around 60 years of age. but for Plácido Domingo, not the least of his amazing accomplishments is that, at the age of 68, he continues to dominate the operatic world.

In 1965, Domingo accepted a contract at the New York City Opera. Debuts soon followed at the Hamburg State Opera, the Vienna State Opera, the Metropolitan in New York and the Royal Opera at Covent Garden in London. The world was his stage. He has appeared in operas and in concerts almost everywhere. He performed a duet with the Chinese singer Song Zuying at the closing ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. As one of the Three Tenors along with his friends José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti, he has consolidated his international fame in concerts, recordings and television broadcasts.

But what about Domingo’s other careers? Remarkably, he has emerged as an important conductor, and he is unique as a singer who has undertaken large-scale conducting duties and at the same time continues to sing.

It might look to the audience as if the conductor doesn’t do much more than swing his or her arms around, start up the ensemble and give a few cues, but in fact it is a demanding job, most of all when conducting an opera. In the orchestra pit of a theatre, a conductor can barely be seen by the audience, so there is not any temptation to show off. And where a symphonic conductor only has to concentrate on the orchestra, an opera conductor has to coordinate stage and pit, exercise authority over both instrumentalists and soloists, and control the chorus. It is not a job for the feeble, or the inexperienced.

Domingo’s conducting interests go back to his earliest musical experiences. His activities in his parents’ zarzuela company included conducting. He recalls observing some classes by the great conductor Igor Markevich in Mexico City, and he developed a close and lasting friendship with fellow student Eduardo Mata, who became a notable conductor. Later, in Vienna, Domingo took lessons from one of the most brilliant teachers of conducting: “I went to Maestro [Hans] Swarowsky—many of the great conductors, they studied with him.” With this kind of background, he came to professional conducting well prepared, but also brought with him a typical Domingo modesty that won over notoriously antagonistic performers. As he says even now, every performance is a learning experience: “Every day, I feel more comfortable.”

In 1973, Julius Rudel, the director of the New York City Opera, let Domingo conduct some performances of La Traviata, one of the works that he knew and sang often. Then, almost surreptitiously, he directed Johann Strauss’s classic Die Fledermaus in Frankfurt and Munich, and then in Vienna, the heartland of operetta. With this same work, in which he had never sung, he made his conducting debut at Covent Garden in London in 1983, securing his international career as a conductor. Domingo mostly conducts opera, but he has ventured into the symphonic world where, not surprisingly, he has shown the same qualities that have made him a great singer. When he conducted the Montreal Symphony Orchestra in the fall of 2005, the Gazette’s Arthur Kaptainis wrote of Domingo’s “long-lined and lyrical approach to Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4”. He has now racked up about 400 performances as a conductor.

Then there is his career as administrator. He has been associated with the Los Angeles Opera since its founding in 1984, and with the Washington National Opera since 1996. He became director of both companies in 2003. Never content to just be a figurehead, Domingo has taken an active part in the operations of the two companies, as an administrator, a singer and a conductor.

Administrator and musician merged in Operalia, an opera competition he established in 1993. Operalia 2008 took place in Quebec City in conjunction with the 400th anniversary of the founding of that city. Operalia is a class act: prizes totalled $175,000 (U.S.) and also included two Rolex watches (Rolex has been the chief sponsor since the beginning), and the 13 jury members included the directors of opera theatres in Paris, London, Lyon, Vienna, Barcelona, Madrid and Quebec City, among others. Although Domingo’s name and patronage would be sufficient to invest the competition with great prestige, he does not just lend his name. He conducts the orchestra for the contestants, as well as the closing concert with the finalists. The 41 contestants from around the world, whether winners or not, will remember the association with one of the greatest, most professional and kindest artists now before the public.

In 2000, the winner at Operalia was the Canadian soprano Isabel Bayrakdarian. She recalls a man who, despite his fame, was “always down-to-earth”; she also remembers the thrill of singing a duet with him, the great artist and the young singer at the beginning of her career performing as artistic equals. If she has one word for Domingo, it is humility.

Domingo remains a force of nature, albeit a relaxed and affable force. Genial, kind, altruistic and a most consummate artist, sustained, as he says of Gluck’s Iphigénie, “by the power of the music”.