Chefs Answer the Common Question: Why Do So Many of Them Have Tattoos?

Knives and needles.

It’s a common stereotype, the chef covered in tattoos. Any look behind the scenes of a busy restaurant will find a confluence of kitchen jargon, flames, and inked skin peeking out from behind chef coats. “The thing about stereotypes is that there are grains of truth to them,” laughs David Zilber, former sous chef at Copenhagen’s Noma. “I started getting tattoos after I started cooking, so I mean, there you go,” continues the chef, currently a food scientist at bioscience company Chr. Hansen. With tattoos scattered along his arms down to his wrists, Zilber looks the part of a chef as much as he does an artist (indeed, he is also a notable photographer). But it’s that indistinction that informs this curious commonality among so many chefs.

“I’ve worked with, like, a whole forgotten caste of society,” Zilber says of his past kitchen mates, referencing ex-cons and people who left school as teenagers. There is no single type of person who becomes a chef, he explains, but the kitchen offers a space for artistic expression. It’s a space of heat, sweat, chaos, and ultimately, creation. A space as fraught with emotion and intensity as an artist’s studio.

Chris Lam of Straight and Marrow. Right arm piece by Andrew Warren. Left arm piece by Mark Ainsworth of Raincity Tattoo.

The late Anthony Bourdain, heavily tattooed himself, found in the kitchen a place for those on the periphery of polite society, the outliers and the outcasts. And within that, an invisible bond became threaded through the intimacy of cooking a meal. When we look closer, the bustle of a kitchen turns into a dance grounded in fast-paced tempo. Deft hands sculpt, twist, and tear at dough; hips sway with the back-and-forth of a wok.

“Cooking is an art form just like tattooing is an art form,” says Isaac Fitzerald, author of Knives & Ink: Chefs and the Stories Behind Their Tattoos. “You create an experience for somebody else.” In Knives & Ink, Fitzgerald interviewed over 65 chefs about their tattoos, garnering a wealth of anecdotal data on why they got inked. In the microcosm of a single kitchen, a larger sense of kinship can be felt. And for many chefs, tattoos are permanent markers of that identity. Through ink, they symbolize both their individual expressionism and a belonging to an outlier community.

Chef Gus Stieffenhofer-Brandson of Published on Main. Side tattoo by Katie Shocrylas.

Entire back by Steve Moore.

Chest piece, left sleeve, and bottom right sleeve by Trish Bee; stomach piece by Karrie Arthurs; side piece by Katie Shocrylas; right sleeve top by Tommy Compton.

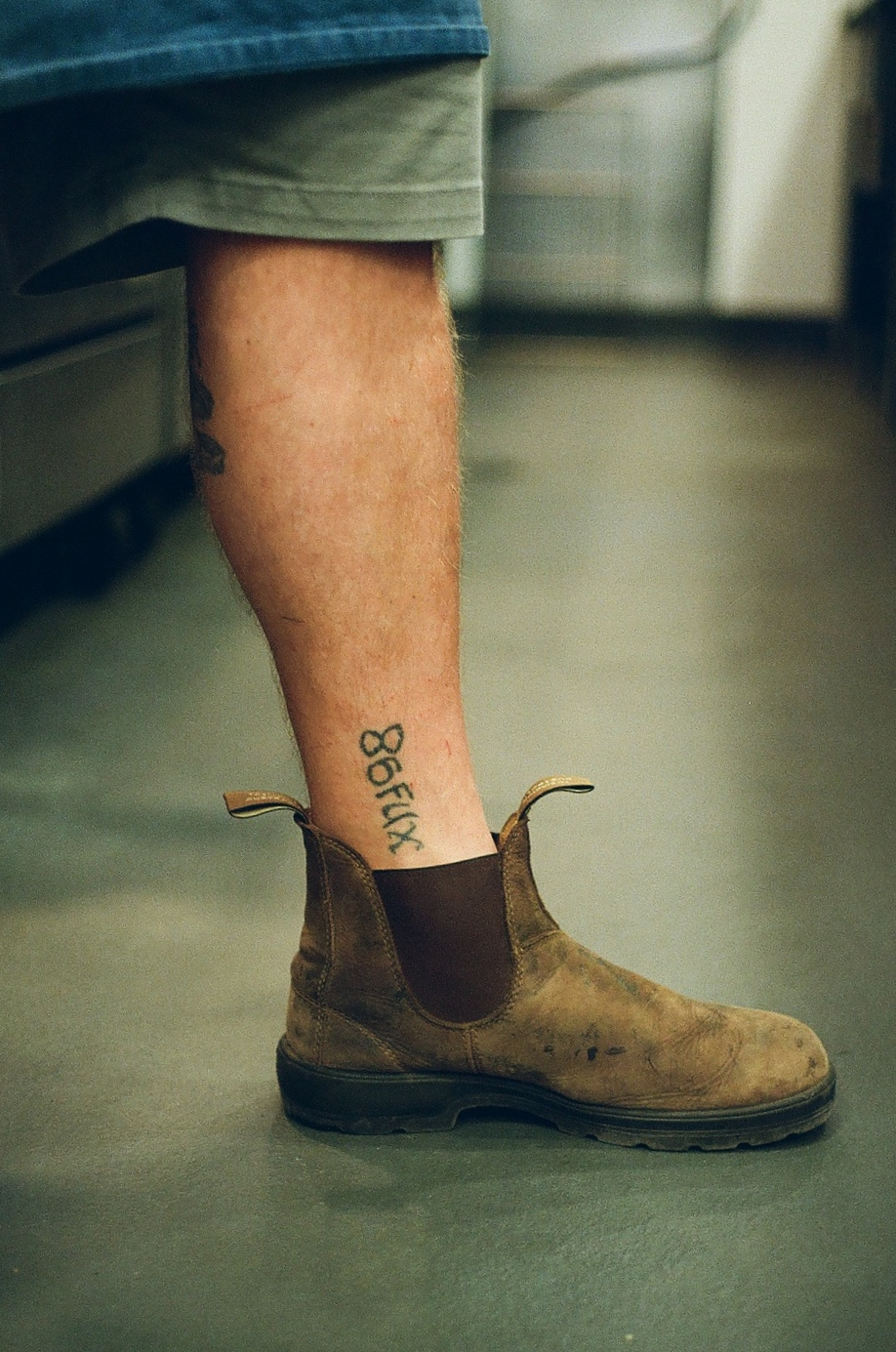

Stick n poke ankle tattoo “86fux” done by a fellow chef is a reference to the temperature for cooked meat.

For some chefs, tattoos are also a vessel for showing their dedication to the trade. “The one thing I heard over and over again [in my interviews] was, ‘By getting this tattoo, I knew it would be harder for me to go out and get that nine-to-five. It made me commit to sticking with the kitchen because this is actually the life that I love,’ ” Fitzgerald recalls. Getting a tattoo in highly visible areas, like the neck or back of the hands, indicates a sort of extreme edge of personality: a dive into the deep end sort of character. Like art, cooking is a life calling, and the ink seals fate.

James Frost of Livia Bakery. Left arm includes: rose dagger by Ali Bruce; small flowers by Ariane Lapointe of Bebop Ink; crybaby by Vanessa Taylor of Bebop Ink; elbow flower by Emily Chou of Grapevine Tattoo. Right arm includes: crying woman by Rose Wild; colorful panther head by Mike Campetelli of Supercat Tattoo.

Right arm snake by Ariane Lapointe at Bebop Ink. Left arm forearm piece by Katrina Rowsell of Desperado Tattoo.

Still, tattoos—even in highly visible spots—are much more normalized in all areas of society compared to a few years ago, even in corporate spaces. “We’re kind of like the tattoo generation. I think everybody has, like, one, you know,” says Chris Lam, chef and owner of Vancouver’s Straight and Marrow, who has full sleeves on both arms. On the more practical side, Lam explains how chefs often get inked to cover their frequent burn marks and scars. “It’s a nice way to turn your burn into something beautiful,” he says.

For Lam, tattoos are also often an indication of industry culture in general. “You have to have a certain personality to be able to survive and thrive in the restaurant industry. Most of us [chefs] are pretty rebellious in nature, and a lot are very creative,” he says.

It’s a commonality Fitzgerald, who used to work at a dive bar in San Francisco, discovered as well. “Tattoo parlours can have almost that same communal vibe that a restaurant or a bar can have,” he says.

“That kind of freedom of expression is what allows people to thrive in kitchens,” Zilber says. “It allows you to think outside the box. It’s a freedom to be yourself and put your ideas through the lens of a culinary translation.”

Wesley Dennis of Sandbar.

Both arms by Jay Doherty of Millenium Ink, North Vancouver.

Chef Cameron Barker of Honey Salt. Black tattoos by Luke Satoru of Black Pig Tattoo, Bangkok.

Photos by Ayesha Habib.