Anthony Bourdain

United states of Bourdain.

It’s hard to believe it’s been 16 years since Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain’s gritty account of sex, drugs, and mise en place, was published. The best-selling book catapulted the then-44-year-old journeyman chef onto the public stage. It made his voice, at once profane and poetic, the trusted narrator for the metastasis of food culture that has occurred since 2000. Sixteen years is a long time. It means there are young adults who have grown up in a wholly post–Bourdain world. They are driving automobiles, celebrating quinceañeras, going to college. It means a few dozen pop stars have risen and fallen since Bourdain became Bourdain. And it means that the 60-year-old, who already seemed to have lived enough for a few lifetimes by the time he wrote his first memoir, is no longer the same Bourdain who glared from its cover.

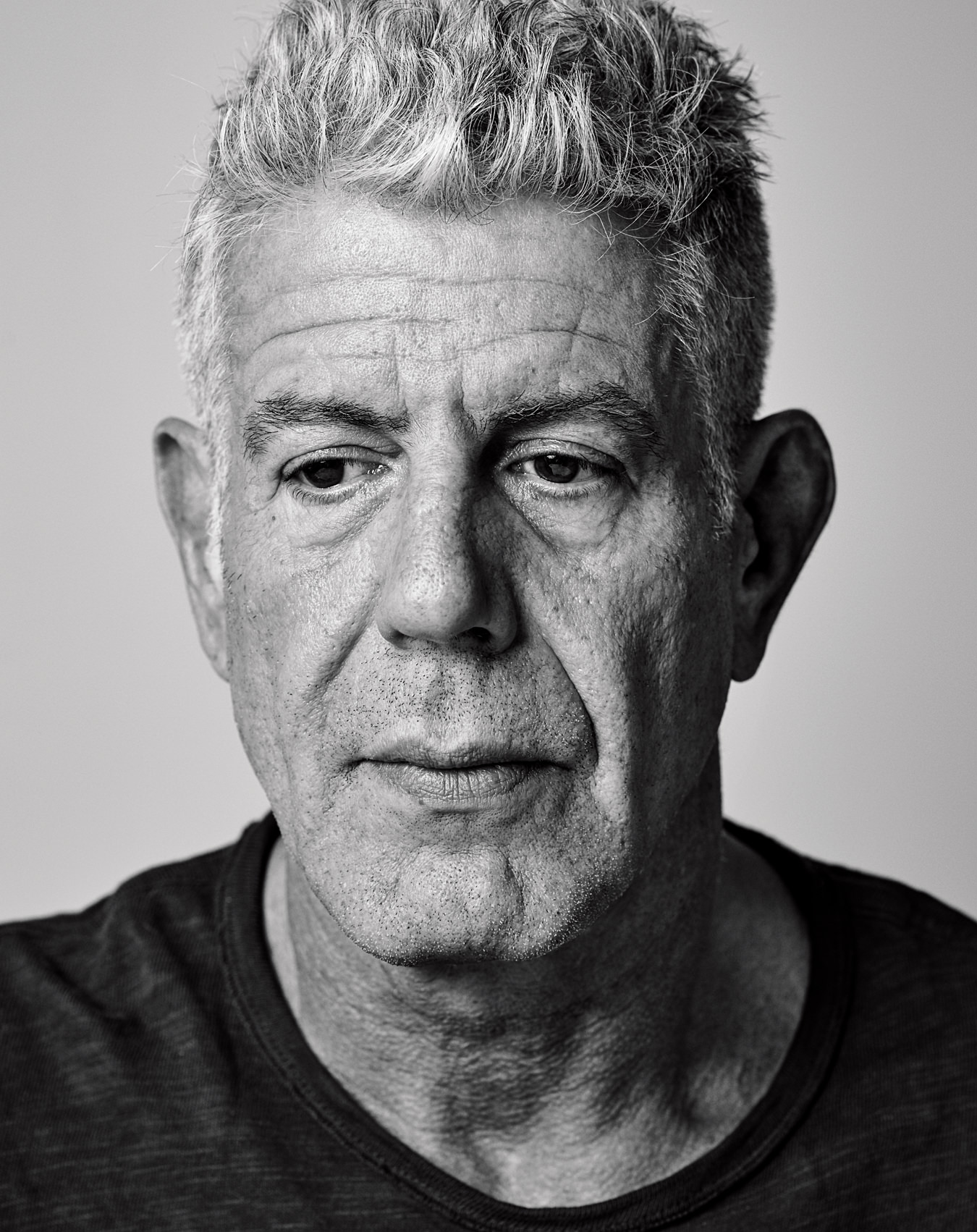

First of all, that mane of black hair and the furrowed, swarthy eyebrows of the young Bourdain, arms crossed on the cover, have greyed into distinguished salt and pepper. His face, as handsome as ever, though now much more ubiquitous, is creased like the pages of a well-read book. And as he settles into a conference room at the New York offices of Zero Point Zero, the production company behind his trail-blazing show No Reservations—and since 2013 the Emmy Award–winning Parts Unknown—he creaks a little, like a comfortable wooden rocker. Now when he moves, he does so with the rambling cadence of an aging cowboy. His loping gait approaches Clint Eastwood badassery, the likes of which I’ve only seen once before. Thomas Keller, chef of the French Laundry, walks this way too. Each step is leisurely and ready for accolade. It is the gait of the adored.

Or perhaps it’s just the walk of the hungover. Though he has certainly mellowed with age, the hard-partying Bourdain will never completely fade to choirboy. “I don’t usually go out,” he admits when I first meet him in the morning, “but my friends were in town.” When pressed, he admits his friends were the Stooges, as in Iggy and the Stooges, one of the most seminal punk bands of all time. Though Iggy Pop, he says, has given up booze for fresh-squeezed juice, the Stooges still throw down. And Bourdain has a reputation to maintain, so it had been, to say the least, a late night.

Alternatively, his slow-moving amble could be the generalized muscle soreness of an athlete. At a time when most people have surrendered or at least strategically retreated from any strenuous physical activity, Bourdain earned his blue belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu last year. (His wife, Ottavia Busia Bourdain, is a jiu-jitsu enthusiast who is working toward becoming an instructor.) At one point, he raises his soft grey T-shirt to polish his reading glasses and reveals a torso that seems transplanted from a man half his age. Those are some calendar-level abs. “I train every day, wherever I am in the world,” he says. “When I’m in New York, I train at the Renzo Gracie Academy, an hour private and then an hour and a half general population. That’s basically Fight Club.”

In fact, in April, a couple of months shy of his 60th birthday, Bourdain was in his first Brazilian jiu-jitsu competition, at the New York Spring International Open Jiu-Jitsu IBJJF Championship. “I assumed I was going to get the crap kicked out of me. Most people who go to these things compete all the time. It’s terrifying.” However, Bourdain’s crap remained firmly within him and he emerged a champion. There’s an Instagram of Bourdain, in a blue gi and a big smile, on the podium. The caption, perhaps atypically for Bourdain, is understated: “First competition turned out okay!”

In effect, Bourdain has become yet another Bourdain—a Brazilian jiu-jitsu champion Bourdain. And why not? This is just one more manifestation of the ever-evolving man.

The 60-year-old, who already seemed to have lived enough for a few lifetimes by the time he wrote his first memoir, is no longer the same Bourdain who glared from its cover.

Having grown up in the suburbs of Philadelphia in the 1990s, I will always think the Phillies who lost the 1993 World Series and the Legion of Doom Flyers were the greatest teams in that city’s history. It doesn’t matter if they are statistically. To me, they are the definitive Philly teams. The same goes if you came of age in Vancouver in the ’80s: the Canucks of ’82 will always hold a mythic place in your personal Hall of Fame. The memories of these cultural moments are encased in the amber of adolescence, forever suspended in glory.

So it is with Bourdain. For those of us who knew of the man in his early, angry years, when he was the profanity-spewing, cigarette-smoking, anything-but-furry epitome of the bad boy chef, that Bourdain will always be the prototypical Bourdain, the Bourdain against which all other Bourdains are judged.

I was in my early 20s when No Reservations burst onto the Travel Channel like no show anyone had ever seen before. It was the hour-long bastard son of Hunter S. Thompson, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, and a Lonely Planet guide. As Bourdain travelled the globe, he came across as someone who was in control, but sometimes barely. He had lost none of the mercurial edge that had made him such a compelling anti-hero in Kitchen Confidential, and part of that show’s charm was just how extreme Bourdain was willing to be. But it wasn’t just his onscreen persona. The mid-aughts also saw the rise of the current—though now somewhat declining—stable of celebrity chefs. This included Paula Deen, Guy Fieri, Sandra Lee, Rocco DiSpirito, and Rachael Ray. These camera-ready caricatures of chefs proved to be the perfect foils for Bourdain. During those years, not a week went by that he didn’t make headlines by saying something wildly provocative about them. He reserved his most venomous invective for Lee. She is, he wrote, “Pure evil. This frightening Hell Spawn of Kathie Lee and Betty Crocker seems on a mission to kill her fans, one meal at a time.” (Sandra Lee is now the erstwhile First Lady of New York state.) Wild hyperbole, very entertaining, morally outraged. This was Bourdain’s thing back then, and that’s hard to reconcile with the Bourdain of today.

What does a guy who made his name being unhappy do when happiness descends upon him like a plague?

This October, Bourdain will release his first cookbook in over a decade, following 2004’s Anthony Bourdain’s Les Halles Cookbook. The book, co-written with Laurie Woolever, is called Appetites, and though there are the trappings of the craven excess of his single years—the cover is by Ralph Steadman, who illustrated Hunter S. Thompson’s masterwork Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The opening layout, a debauched tableau, features a decapitated boar’s head wearing novelty glasses and Bourdain, mid-bite with his tie undone; his wife, face full of chicken, is wearing a rash guard. As well, there’s a mystery man in a Bruce Lee T-shirt and a duck mask—chef Eric Ripert of Le Bernardin caught in the unflattering act of spitting wine out before a table laden with a bacchanalian spread—the book is, in essence, a feel-good family affair. The epigraph is the first half of Leo Tolstoy’s famous opening line, “All happy families are alike.” Tellingly, he leaves out the much darker second half: “Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

For Bourdain’s family life is, in fact, happy. Strange, but happy. “I have an unconventional family,” he admits. “But who has a conventional family? My house generally is my nine-year-old daughter, Ariane; my wife, Ottavia, in a rash guard, if she’s home at all because she’s usually training for fighting all the time; and this extended family of Filipinos, friends of my daughter, who’ve become family too.”

“Everyone lies in cookbooks. That’s why they’re generally so frustrating.”

The recipes in these pages are what Bourdain cooks for his loved ones: scrambled eggs, roast chicken with lemon and thyme, a turkey at Thanksgiving. The concept of cooking for loved ones is a relatively new experience for the man. “As somebody who cooked professionally for 30 years,” he says, “I only saw the normal world as dark silhouettes in the dining room. I was never home. I had no idea what people did on weekends or what it’s like to have a family.”

Now he knows, and he’s quite smitten. “When I get to be a stay-at-home dad for a week here, a month there, I really take to it,” he gushes. “It’s an exotic activity for me, so I enjoy it probably much more than is healthy.” Bourdain being Bourdain, he brings the same sort of intensity to preparing his daughter’s lunches as he did working the line. Whether it’s food to send to school or what’s eaten on family vacations, he still prepares cycle menus. “My meal plans are mapped out Monday through Sunday, with interrelated lunches and dinners,” he explains, reverting to the tone a chef uses when talking shop.

Within the pages of Appetites and in conversation with Bourdain, there are still hints of latent anger. Mostly this is manifest in the frequent and indiscriminate use of the word fuck. The recipe for steak appears on a bloody page with a headline that reads Big Fucking Steak. Similarly, the first line of the dessert section is “Fuck desserts,” though the next line is, “OK. I don’t mean that.” His opinions are still emphatically delivered. There are some things Bourdain strongly opposes. The third slice of bread in the club sandwich. The brioche bun on the hamburger. Toasting the muffin on only one side when you make eggs Benedict. To him, “These are terrible food crimes!”

But the tough talk of the book is meant not to discourage his readers, but to quiet their insecurity in the kitchen. “Everyone lies in cookbooks,” he complains. “That’s why they’re generally so frustrating. Nobody ever tells you, for instance, that you’re going to screw up hollandaise. It’s not gonna happen for you the first time. It takes professionals many repeated times.”

The recipes in Appetites are what Bourdain cooks for his loved ones, but the concept of cooking for loved ones is a relatively new experience for the man.

So what does a guy who made his name being unhappy do when happiness descends upon him like a plague? If you’re Bourdain, you roll with it. If you watch Parts Unknown now, he spends a lot more time listening than he does talking. Part of this openness, he says, is the result of becoming a father. “When you have a child, you’re no longer the star of the movie. Right away, the whole universe shifts to the right or the left. That’s a huge relief, frankly, and a joy.”

In the streets of Tbilisi or Addis Ababa, he walks slowly perhaps not from creaking bones but to actually see. “When I ask simple questions like, ‘What do you like to eat,’ people all of a sudden start telling you the most extraordinary things.”

It’s hard to imagine what the strung-out, high-strung Bourdain of 16 years ago would think of Instagram activity posted of himself and President Obama sharing a $6 bun cha dinner at a hole in the wall in Hanoi. He might have been too busy being outrageous to notice. But the Bourdain of today is having a blast. Whether packing his daughter’s school lunches or dining with the president, he is guided by the same simple philosophy: “You want to be at your own party.”