On Beauty and Violence With Dana Claxton

The Hunkpapa Lakota multidisciplinary artist draws from Indigenous histories to consider the contemporary.

“The Lakota have a philosophy,” Dana Claxton tells me: “Everything you need to know is in the sky.” In her hometown of Moose Jaw, the endless expanse of the above, mirrored below by the vast reaches of the Great Plains, is what first prodded at the future artist’s sensibilities. Through the endlessness of Skan—the sky being and spirit giver in Lakota culture—Claxton sensed an infinite potentiality, a source of inspiration that would rouse her own potential as an artist.

In her 30-year career, Claxton has amassed a multidisciplinary body of work as expansive as the sky. Exhibited globally, her art is centred on Indigenous narratives—told through film, photography, performance, and mixed-media installations—to challenge stereotypes and diagnose the symptoms of colonial legacies. “The core themes of my practice rest in ideas of spirit, land, social justice, and representation,” she says. Rooted in imagery of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux band, who followed Sitting Bull to Saskatchewan from the United States and from whom Claxton herself descends, Claxton’s work situates the Indigenous identity within contemporary contexts.

It took years, however, for Claxton to realize her artistic potential. A self-described “late-bloomer” when it comes to art, she says her journey into the field began simply with looking. In understanding the concept of the infinite, be it in the skies or the minutiae of her Euro-Canadian grandmother’s vegetable garden. “I had my first serious camera at 16—a Canon AE-1. I took gads of photos, but it took me awhile to realize I was an artist,” she says.

Perhaps it was when she moved to Vancouver in the mid-eighties and began training at Spirit Song Native Indian Theatre Company that the reality of her artistic identity fully took hold. At the time, Spirit Song was a theatre production training centre for Indigenous youth. “It was a very active place in the eighties and a little bit into the nineties for urban Indians,” Claxton recalls, listing playwright Marie Clements as a past alumnus. “If you had any kind of creative inclination, you would go and study there.”

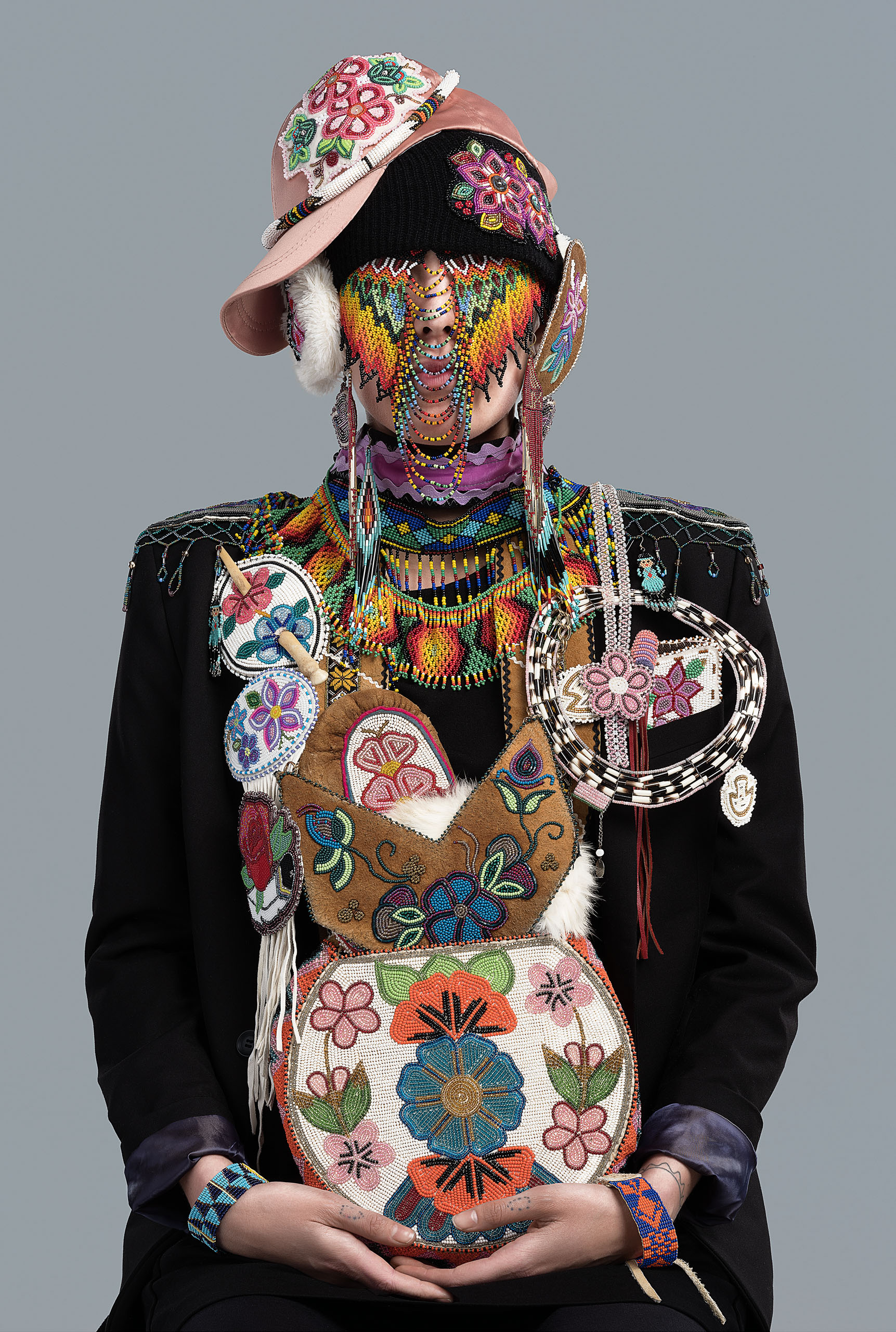

Dana Claxton references historical and contemporary violence in her work. But there is also an imbued sense of beauty throughout. Pieces like Headdress – Jeneen (2018), pictured here, speak to cultural appropriation while honouring the elaborate beauty of beadwork.

With Spirit Song now shut down, I ask Claxton if there are any equivalent spaces today. She tells me about Full Circle, a theatre company run by legendary theatre actress Margo Kane, while emphasizing the importance of having these spaces to foster Indigenous creativity. “The creative and performing arts for youth and adults is imperative to storytelling and ‘storying’ our nations,” she says.

It was at Spirit Song that Claxton developed the skills that would make her the artist she is today; she even took an arts administration course that she would draw from decades later as head of the art history, visual art, and theory department at the University of British Columbia. “I wrote some plays at Spirit Song, then I turned those short plays into short film scripts and made a few short films, and then everything fell into place,” she says.

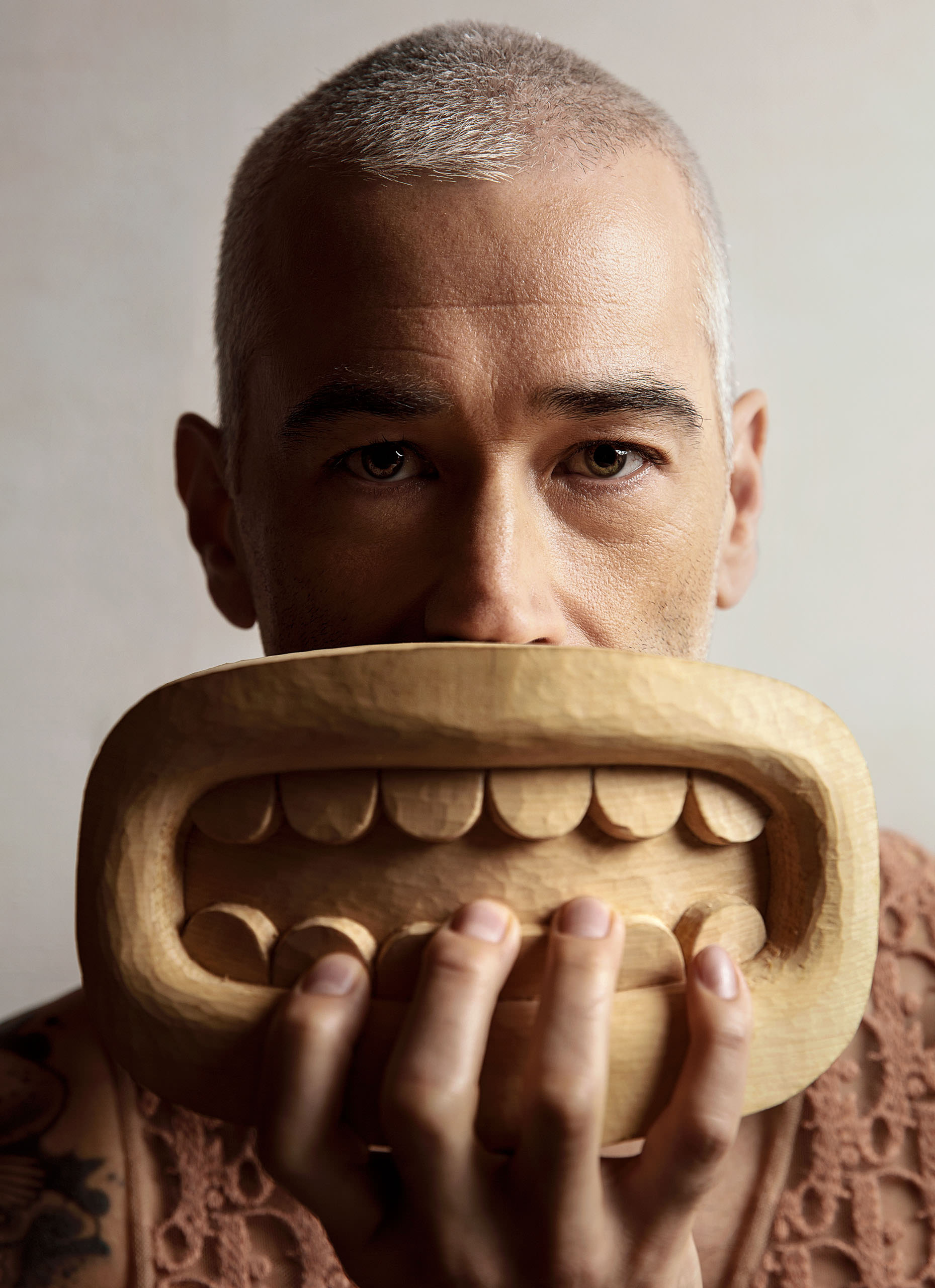

Dana Claxton, photographed at Arts Umbrella in Vancouver wearing silver earrings designed by Morgan Asoyuf.

Claxton’s experimental piece Buffalo Bone China (1997) was the harbinger of her influence within the art world. The 12-minute film is a reckoning of colonial practices and homage to the American bison—a symbol of spiritual significance and source of livelihood for Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains. Colonial policy in the 19th century saw a sweeping and sanctioned near-destruction of the mammal’s population. Buffalo bone was used for a number of purposes for English settlers, including using the ground-up bone to make fine china.

A mix of found footage and performance art, Buffalo Bone China features video of roaming buffalo contrasted with images of the animal’s bleached bones and the smashing of fine china made from buffalo bone. These images, shown in progression, tell a story of twofold massacre: that of the bison and of the First Nations deprived of their means of survival. Smashing the china is a significant revolt, while the opulence of these objects juxtaposed against the violence behind their materials is poignant.

Dana Claxton is self-aware of the inherent political nature of her existence. “The old saying comes to mind: the personal is political,” she says. “I suppose being part of a history that has legally subjugated Indigenous people makes me a political subject—or is it a political object?”

Claxton’s work has been described as “political,” a term almost inescapable when considering contemporary Indigenous work from the outside in. And while her later pieces surround Indigenous identity in a postcolonial light, she is self-aware of the inherent political nature of her existence. “The old saying comes to mind: the personal is political,” she says. “I suppose being part of a history that has legally subjugated Indigenous people makes me a political subject—or is it a political object? There are a lot of ghosts haunting the Canadian colonial landscape. The decolonial work is unfolding every day for Indigenous people and settlers’ descendants and newcomers. They need to dig deep to consider what kind of relations they are in with Indigenous people, unpack cultural bias, and look to new understandings.”

Dana wears Wood Mountain moccasins from her home reserve, made by the late Grace Peigan.

Indian Candy, her 2013 series, as one example, considers these long-standing cultural biases with a sly wit and explosion of colour—an idiosyncratic tone Claxton has come to be known for. The series reinvents the “whitewashed” iconography of the Wild West into highly stylized pop art homages. Hollywood-enforced stereotypes are considered in a studio photo of the character Tonto in The Lone Ranger, captioned “Tonto Pray for you” in magenta. Claxton adds neon saturation to archived historical documents, such as ones referencing W.F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody—the infamous American bison hunter who founded his own circus-like Wild West show—and Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux leader who would later appear in Buffalo Bill’s show after failing to resist American expansion.

“You know, sometimes you just need candy. Or something that is delicious, colourful, and shiny,” Claxton says of the series’ title, with an edge of her defining humour. “These works chart official documents of Canadian and American expansion and bring some of those hidden histories forward. The title itself, Indian Candy, is fraught, as the word Indian is so problematic.”

Aside from her work with film and found objects, Claxton’s own photographic pieces have a striking and almost surreal quality. The Mustang Suite, her 2008 collection of photographs depicting a Native American family each with their own version of a mustang (horse, bike, car), contrasts contemporary and traditional imagery. Each member gazes into the camera with a stiffness in their body language reminiscent of a forced family portrait. Claxton makes ample use of the colour red throughout the series, a significant hue in Lakota Sioux culture with powerful Western connotations as well. Her visual language brims with subtle undertones contrasted with stark colours.

“Although inside the frame, I create images that tell a story, I am also pondering what is going on outside the frame. What makes the image what it is includes history and the present. I bring into images this enormous complex history and fold it into almost every image I make.” —Dana Claxton

But, with Claxton’s work, what is not shown is as important as what is shown. “Although inside the frame, I create images that tell a story—sometimes complex, other times less complex—I am also pondering what is going on outside the frame,” she explains. “What makes the image what it is—I suppose the backstory—includes history and the present. I bring into images this enormous complex history and fold it into almost every image I make.”

Folded into her work is also a sense of beauty. For all the historical violence her pieces reference, there is also an imbued beauty in the details. While her Headdress (2018–2019) series, which features five women wearing traditional headdresses, is a commentary on cultural appropriation, the elaborate beadwork pieces shrouding its wearers with its own immensity cannot but otherwise be appreciated for their intricate beauty. “I was considering the fetish for wearing war bonnets,” Claxton says of the series. “War bonnets, a.k.a headdresses, are worn by dignitaries, and, in the case of Lakota culture, they were for battle. These are not fashion items to be worn lightly, and one generally has lived a certain way and performed certain deeds and duties to be honoured and gifted with one.”

For Claxton, beauty is found in the most delicate details and the most abstract qualities: “A decaying painted-blue exterior wall, spring bulbs, the thunder beings, a child’s laughter,” she says. It’s a sensibility that translates to her work, which tenderly lays beauty and violence alongside each other. “I believe in beauty and pleasure, while hoping for critical consciousness for viewers,” she says. “Life is beautiful, even with its devastations.”

Dana wears yellow beaded earrings by Shadae Johnson-Paul.