Patkau Architects

Material considerations.

Touring the world, you might be tempted to conclude that cities are just abstractions of international finance—we build what the market demands. But when you encounter the work of John and Patricia Patkau, you realize there are still artists’ hands at work. The two artist-architects, who are based in condo-crazed Vancouver, have been steadily working for four decades, as though immune to market pressures.

The Patkaus are giants in the Canadian architectural world—their work is studied in universities around the globe—but they do not use their heft to produce 80-storey towers punctuating urban centres. Nor do they concoct megalithic headquarters to express some corporate ego. Instead, quietly, as though divorced from the entire red-faced game that city building can be, the Patkaus focus on ideas: the pure, unembarrassed inquiry that precedes and infuses all truly great designs.

Consider this assignment from 2010. The foundation that oversees the property surrounding Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary Fallingwater house invited a select group of architects to submit proposals for a series of artist-residence cottages to be built nearby. Dozens of heavyweight firms laboured over their submissions. The Patkaus ousted them all. Their winning design was the polar opposite of a showpiece: the cottages slip under the hillocks that wave across the 5,000 acres of Pennsylvania grassland surrounding Fallingwater. Where others tried for modernist jewel boxes or Gehry-esque fantasias, the Patkaus produced Hobbit-hole-like habitations, complete with curved, cocoon-like interiors. By nearly disappearing into the landscape, their cottages would make residents, quite literally, at home in the natural world. And, in doing so, they’d remain true to a core idea of Wright’s: the late master wrote in his autobiography, “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.” The Patkaus took him at his word. And then they sought to bring that word to life.

The Audain Art Museum in Whistler, B.C. Photo by James Dow/Patkau Architects.

The cottages were designed to be serene spaces, positioned in a high meadow with a view of that leaf-peeping mecca, the Laurel Highlands; they were to be a marvellous addition to North America’s architectural landscape and a careful adjunct to perhaps the single greatest house in this hemisphere. But they were never built. Much of the Patkaus’ work seems to live in their heads, in a landscape of experiment and philosophy rather than brick and mortar. I once asked The Globe and Mail’s architecture critic at the time, Lisa Rochon, what it was that made the Patkaus so different from others in their field. She summed it up perfectly: “Most build, they sculpt.”

I’m meeting the pair at the Polygon Gallery, which they designed, on the shore in North Vancouver next to Lonsdale Quay. Twenty-five thousand square feet of industrial grating and glass enrobe two storeys of gallery space, all perched on the water’s edge. The building’s façade is made of the same textured gangways used in marinas, but the second-floor gallery, where we meet, boasts an enormous wall of retractable windows that breaks through the cladding, inviting views of the harbour and downtown Vancouver beyond. Against the distant cityscape, the room is spacious, empty, refined.

Upon my arrival, the Patkaus arrange a couple of benches I hadn’t noticed at first, and we sit facing each other with an absurd amount of breathing space. It’s like arriving for a formal dinner at the centre of an empty gymnasium. Patricia and John are dressed in their customary black (never have I seen either wearing a colour), but their shared demeanour is warmer than their outfits. Patricia is soft spoken, with friendly owlish eyes and a tendency to chuckle after strong statements. John is more hawkish and he does not veer from pronouncements. In conversation they appear to be co-equal parts of a single intelligence: a dynamic of the circuitous and the direct, rumination and decision. Patricia and John Patkau have a tendency to finish each other’s sentences, to embroider upon each other’s ideas. It’s tempting to think of their entire practice as a brilliant dinner table conversation that never quite ended.

Hadaway house in Whistler, B.C. Photo by James Dow/Patkau Architects.

That conversation is propelled by a shared love of research. Beginning a decade ago, the Patkaus made that passion official by devising a series of research projects that could feed their curiosity. Patricia had taught at the University of British Columbia for 20 years (and UCLA before). When she retired from campus life, the pair found that the academic ingredient was greatly missed; professorial work had fed their practice with fresh ideas in a way that mere commissions never could. “Teaching made me curiouser and curiouser,” says Patricia. “I wanted something that brought back that joy.” And so, their studio began assigning itself homework—the Patkaus became both professors and students. All that research may or may not result in actual building elements (some research projects gestate for years without revealing any utility). But it always focuses on the nature of some building material—so there’s always the potential for practical application.

First they explored bendy-ply—an open-grained plywood that revealed new possibilities of form. (It was bendy-ply that was meant to be used in the curved interiors of those Hobbit-hole-like homes at Fallingwater.) Their second experiment tackled sheets of stainless steel. Their third looked at beams of two-by-six lumber. No material is beyond their interrogation: they’ve even devoted time to studying pantyhose. Around 15 of these projects can be described in practical terms; dozens of others haven’t gone anywhere yet—they float in a stew of the Patkaus’ curiosity.

With each experiment, force is applied to materials so that new possibilities can emerge. What happens when this block of wood or this slab of quartz is pressurized, hammered, snapped? How do different materials yield in different ways? John summarizes their approach: “Material plus force equals form.”

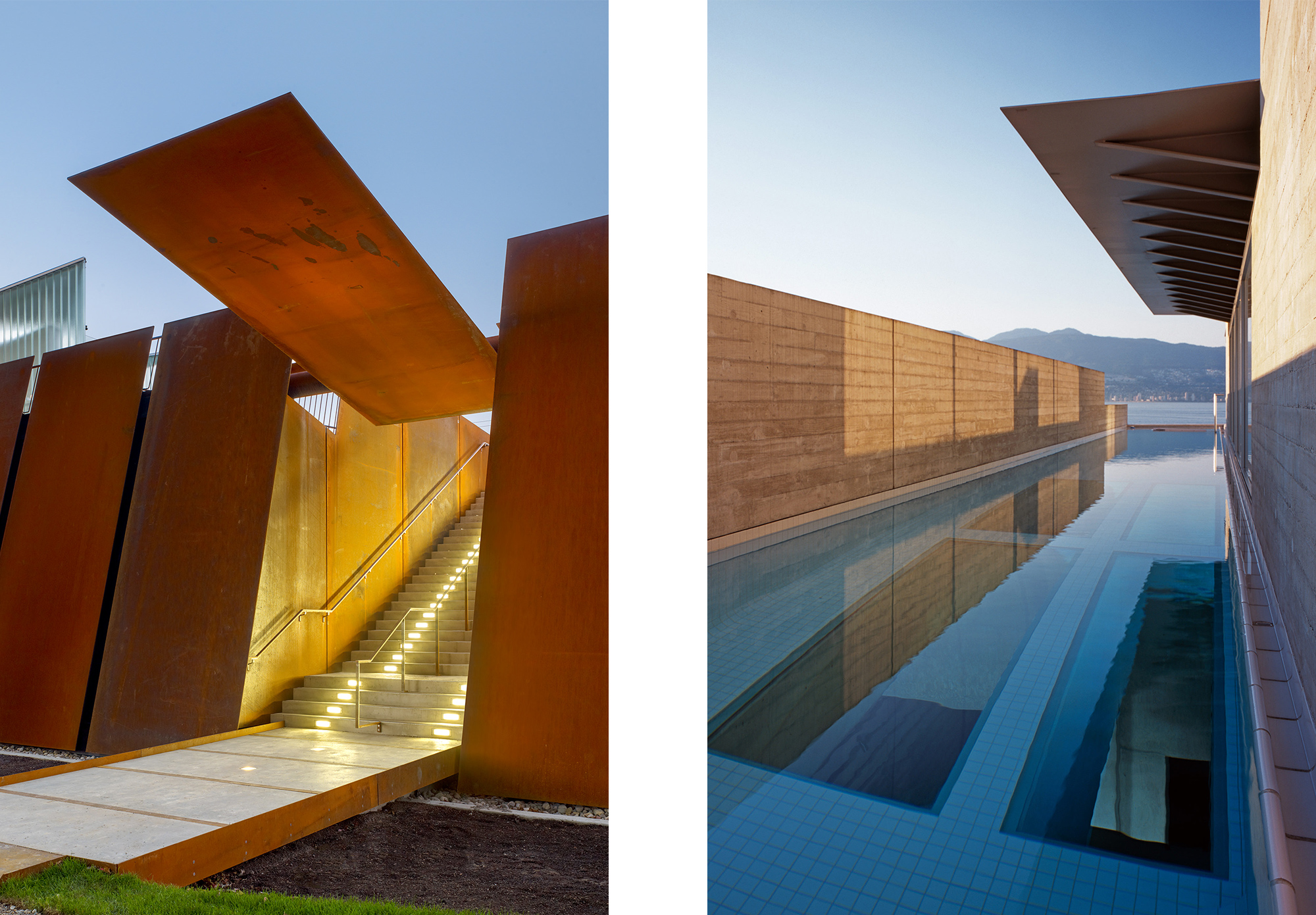

Left: Fort York National Historic Site Visitors Centre in Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban. Right: Shaw House in Vancouver’s English Bay. Photo by Paul Warchol.

When the Patkaus became interested in steel, for example, they took heavy sheets of it—three-eighths of an inch thick—and cut into them, carving lines and shapes. Then they took the sheets to a steelyard, where they used a crane to pull on them with 20,000 pounds of force—until the perforated steel popped, revealing startling new shapes. The sheets became organic bodies, objects of strange beauty. “Some of these projects lead to architecture quite easily,” says Patricia, “and others lead into art.” The categories are equally valuable and the Patkaus are in no rush to make any experiment “useful”.

In scientific fields the most profound breakthroughs emerge from what’s called “pure science”—that is, research free from practical considerations, research that’s allowed to meander. The Patkaus engage in a similarly pure research. By taking the longer, more curious road, they arrive at unexpected destinations. “Architects are trained to draw first and then figure out how it works,” John notes. “But we’ve moved that conversation earlier so it informs the initial conception.” By inquiring into the fundamental nature of materials and the forms that those materials naturally produce, the Patkaus allow the unexpected foibles of nature to guide their artistic vision.

So, it should surprise no one that the latest Patkau project pushes a material to its limit. The Patkaus pair (in partnership with Toronto’s MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects) are designing an 80-metre wooden tower that, when it’s completed in 2020, will be the tallest wood structure in North America. The tower will be located on the University of Toronto’s downtown campus, and will contain classrooms and academic offices in a shell of cross-laminated timber. CLT—a relatively new material—allows larger, stronger pieces of wood to be used in construction, upsizing the potential scale of a building. “Plyscrapers”, as they’re sometimes called, are being erected by developers around the world. The continent’s current tallest CLT structure, at the University of British Columbia, stands 53 metres tall, two-thirds the height of the Patkaus’ vision.

Linear House on Salt Spring Island, B.C. Photo by James Dow/Patkau Architects.

Of course, the Patkaus don’t need to measure their worth by the metre. Their firm has received 18 Governor General’s Awards and eight Lieutenant Governor’s Awards; their work is constantly winning design competitions and filling the pages of magazines and journals. They’ve given us libraries, houses, schools, and enviable private residences. In just the past few years, they produced the Audain Art Museum in Whistler, a gallery space that brings together B.C.’s natural environment and art inspired by it. They also produced the Temple of Light in Kootenay Bay, which opens gorgeous, shell-like segments of roof to the heavens. On Salt Spring Island, they produced Linear House, whose modernist lines and generous banks of windows make up one of the finest homes yet built in Canada.

Of course, they’ve also produced the Polygon Gallery, where we’ve been sitting. It occurs to me, as our interview comes to a close, that we are speaking inside another Patkau experiment, a material manifestation of their curiosity. There’s peace of mind in the wide and gentle steps approaching this room, a marriage of common sense and ingenuity in the sawtooth roof that directs natural light from the north, just so.

I’ve interviewed many architects over the years—often inside their creations—and they usually race around the building, listing details as though running down a spec sheet. Not so with the Patkaus. Only when interviewing contemplative masters like Arthur Erickson or Bing Thom have I encountered such quietude. Theirs is a personal, intimate, life-long inquiry into building materials and light-flooded space. And one would expect no less from a firm whose primary partners are partners in life as well. Once, when we were all sitting at their nondescript offices on West 6th Avenue, John Patkau was describing the moment when they arrived in Vancouver (from Alberta) in 1984: “The first thing we did is we built a house for ourselves; we had no other jobs. We bought half an acre of land in West Vancouver for $89,000.” Patricia added, “We still live there and we’re still finishing it.”

And then John held out a hand as though to say, You must understand this. “The difference, of course, between building a house for yourself and building it for customers is that you never stop working on the house you build for yourself.”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.