Kenneth Cobonpue

Material worth.

Filipino designer Kenneth Cobonpue’s furniture is woven from light and air as much as rattan and steel. His chairs blossom outward, the seats forming supple cascades of petals—seemingly still in the act of growing—that bristle willfully upward. Beds, too, billow as if they belong more properly to the sky. Even a piece inspired by the dim, vaulted domes of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul appears featherweight and latticed with light, while one of the many restaurants and hotel interiors that he has furnished resembles a coral reef or a constellation. His furniture—rich with texture born not of decoration but of the materials and techniques used to make it—tends to make any interior design a showcase for his own designs (for example, the sculpted tropical grotto of Nobu Dubai; the throne-like red chairs of the Blue Monkey restaurant in Amirandes Grecotel Exclusive Resort in Crete, Greece). On his native Cebu, an island in the archipelago that is the Philippines, 45-year-old Cobonpue (pronounced Koh-bahn-pwe) runs two design labels—Kenneth Cobonpue, quite possibly the only global luxury brand made entirely in the Philippines, and Hive, a collective of like-minded Filipino and international designers—predicating both on the use of natural materials, an organic aesthetic, and intense hand-making.

Cobonpue is simultaneously soft-spoken and straight talking. His face shines when he smiles over an obstinate determination, like a reed stretched taut over steel poles. A similar tension exists in the simultaneously porous and sheltering construction of much of his work: the Hagia bed is made from recycled polyethylene wrapped around a powder-coated steel frame and bound with very thin nylon wire, which gives the impression that 1) the arching structure should spring straight again at any moment, but 2) it won’t. “Some of my pieces use the structural principles of tension and compression,” he says. “It’s wonderful to hold something together, not with glue but with the laws of nature. I try to minimize braces or fasteners to allow the individual parts to play their role within the whole and am always fascinated by structure—especially those found in nature, because I believe they contain the solutions to all of our problems.”

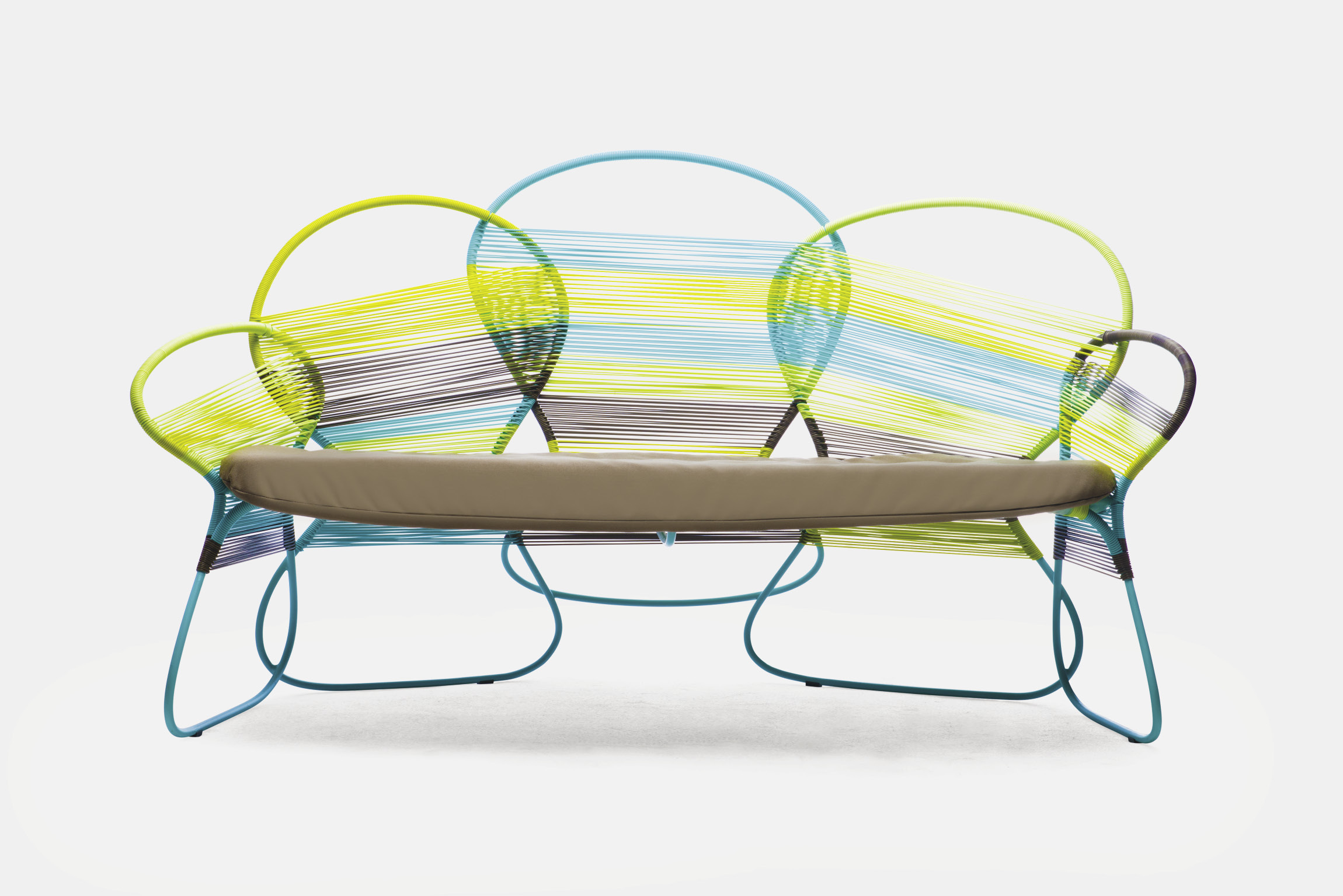

The Trame loveseat is a modern interpretation of the traditional art of weaving: five interlocking asymmetrical loops create the structural frame.

Cobonpue’s mother, Betty, was a designer, maker, and innovator who looked for new solutions and used natural materials; she started her business, Interior Crafts of the Islands, in the family’s backyard, exploring ways to work with rattan until she patented her own process in 1983. This consisted of laminating finely cut pieces of rattan vine and using glue and fine nails to shape them over a mould, giving objects a sculptural quality. “Rattan furniture in the eighties was either very structural, using thick poles lashed together with leather, or woven like wicker,” says Cobonpue. “My mother took fine rattan vines that were used for basket framing and created a fabric-like skin by joining them side by side. The furniture she made looked very soft, sensuous, and sculptural.” While all the other furniture companies in Cebu were doing reproductions for export under someone else’s brand name, she was designing original furniture born from her material experiments and developing her garden workshop into a factory. Her son took her example to heart; even in the fallow first few years when he could sell nothing—not even the now widely recognized La Luna chair or the boxy yet barely there Yin & Yang, a lounge chair through which light flows freely (and which his mother helped him to conceptualize in 1997)—he refused to sell to buyers who would not acknowledge a designer’s authorship or that the pieces were produced in the Philippines. On this, Cobonpue was unyielding. But during the first Movement 8 Filipino trade fair exhibition in 1999 with seven other designers, including Milo Naval and Tes Pasola, the market began to yield to him instead.

Since then, Cobonpue has been lauded and urged on by the likes of Ross Lovegrove and Marcel Wanders, and his work collected by Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, as well as Queen Rania Al Abdullah of Jordan, and the sultan of Brunei. Aside from the furniture and hospitality interiors, he also worked as the concept designer on Manila’s long-delayed Ninoy Aquino International Airport, and is developing an electric car (with E-Motors) and an electric tricycle that will be mass-produced to replace one of the biggest contributors to smog in Southeast Asia, the three-wheeled tuk-tuk. “The challenge to build a unique, affordable, durable, and sustainable design is formidable,” he admits, although responsible design, manufacturing, and waste management are standard practice at both KC and Hive. The wood comes from certified mills and local green plantations; the abaca, buri, rattan, and bamboo, all renewable natural fibres, are being planted in tandem with wood reforestation programs; and all the emphasis on hand making means that the heavy energy consumption of machine production is eliminated.

Kenneth Cobonpue’s furniture—rich with texture born not of decoration but of the materials and techniques used to make it—tends to make any interior design a showcase for his own designs.

Cobonpue is clearly in tune with what the world market wants. Aside from sustainability, he has also been riding the leading edge of a Western wave buoying the production of hybrid indoor-outdoor furnishings. Living on a tropical island has long inspired him to work with natural materials, but “over the years, the distinction between indoor and outdoor living has blurred, and people now entertain more and more outside,” Cobonpue says. “The need for furniture that can withstand the elements was apparent, and so I began to replace the natural fibres with recyclable polyethylene while keeping the same aesthetics.” Today, the outdoor market represents about half of the designer’s business.

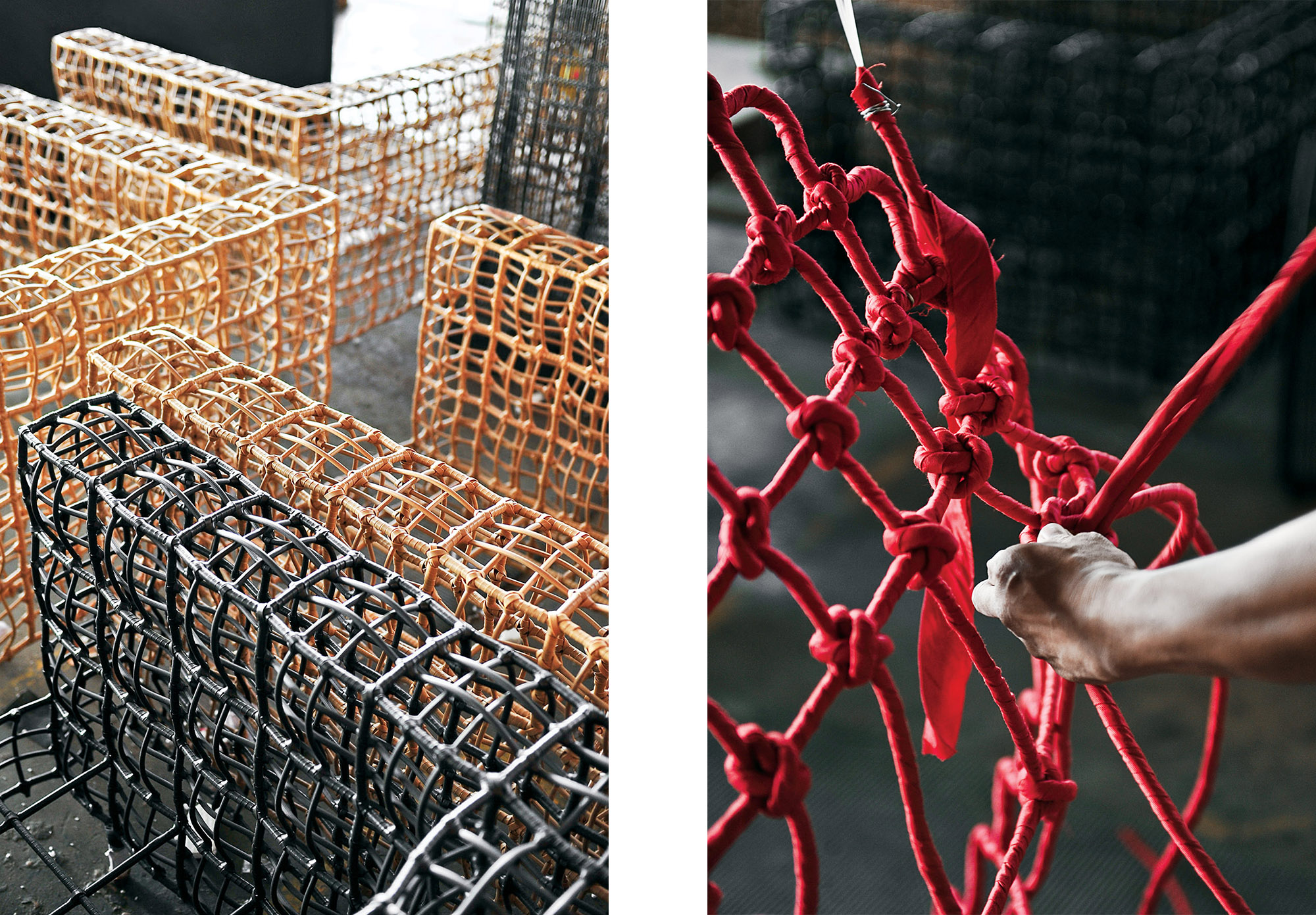

Furniture in progress at the factory in Cebu, Philippines, where the hands of 300 craftspeople materialize Kenneth Cobonpue designs. A craftsperson works on a knotted pattern at Kenneth Cobonpue’s factory in Cebu, Philippines.

To understand how the rest of the world lives, and to get a glimpse of the world market for which he would be designing, Cobonpue left the Philippines in 1987 to live abroad for nine years. While attending business school upon his father’s urging, at the University of the Philippines Diliman campus, Cobonpue found himself failing to balance the financial statements on an exam, so after two years, he transferred into a design program instead. But he couldn’t draw very well either, and he went on to fail a drawing exam that would have gotten him into art school proper. Undiscouraged, Cobonpue took a year off to learn how to draw with local Cebuano artists. Finally, his skills much improved, and he moved to New York to earn his industrial design degree with honours at the Pratt Institute. Today, he uses the computer only to document a piece after it’s built and ready to be introduced. “I use drawing as a tool for the exploration of ideas,” he says. “I don’t use a computer at all during my design process. I visualize the form in my mind and use drawing to translate it onto paper. I always go back to what feels natural and instinctive, which means picking up a pen and drawing what immediately comes to mind.”

The designer augmented his classroom learning with an apprenticeship at a leather workshop in Val d’Arno, Tuscany, and in 1994, on a state scholarship, he studied furniture marketing and production in Munich and Beverungen, Germany. Cobonpue, who learned to speak both Italian and German, says, “In Germany, they build furniture like they manufacture automobiles. I also learned the most about modern design there because many German homes actually look as if they came out of the pages of Italian furniture catalogues.” Germany was also where he fell in love with his wife, Susan Wild, with whom he has two teenage boys, Julian and Andre. Wild oversees the production operation of the company, provides order and systems where needed, and, according to Cobonpue, is his “sweetest critic”.

In 1997, following the death of his father, Cobonpue returned home for good at the age of 28. His father had left a number of businesses in operation. “My idea of running a business was shaped by what my father used to say, that business was common sense,” says Cobonpue. “Back then, my father—a quintessential Chinese trader—had a car dealership, a realty firm, a travel agency, an office equipment depot, and a lending company. I wanted to find something that I had a passion for, so when he passed away, I closed his other businesses even at the risk of financial failure.” (Cobonpue shut most of them down except for the travel agency, which his sister runs, and the realty firm.)

Kenneth Cobonpue’s factory is located in five old warehouses partitioned according to the expertise of the craftspeople who make the products. A weaver works on an intricate project in the factory’s weaving area.

After living abroad, he was also seeing his country with fresh eyes. “When I finally came home, what really surprised me was how slow things are in the Philippines. It takes so long to accomplish even a single task, so it focused me on the importance of efficiency and planning,” he explains. “Most disconcerting, though, was when I realized that I couldn’t actually apply what I had learned by studying industrial design—to mass-produce objects using machines wasn’t applicable, because most of the work in the Philippines was done by hand. But this reality gave me a renewed appreciation for the things I had taken for granted growing up, one being the skill and dexterity of my countrymen when it came to making and improvising things in the absence of machines.”

Today, the factory is located in five old warehouses partitioned according to the expertise—ranging from weaving and upholstering to metalworking—of the 300 craftspeople who make his products. Weavers work on individual mats in the weaving area; there is a full woodworking facility; and the finishing area looks industrial, with spray booths and work tables for each artisan. A new, separate, and eco-conscious building contains special projects; here the finest craftsmen conduct research, make samples, and build prototypes and installations. They are developing the electric tricycle, repairing company cars, and sometimes restoring vintage, handcrafted sports cars from Cobonpue’s own collection, including a Jaguar E-Type, a Ferrari Dino, and a Porsche 356 convertible (mostly Italian and British design icons from the sixties and early seventies). In a second facility, another 100 artisans handcraft the Hive lighting and accessories by local and international designers—among them Holland-born, Hong Kong–based Danny Fang; Harry Allen from New York; Francis Dravigny from Lyon, France; Lilianna Manahan from Manila; and Australian-born, Singapore-based Jarrod Lim.

Cobonpue and his design team usually create small three-dimensional models and develop a dozen swatches before building actual models from basic materials. “A lot of experimentation and exploration of materials take place before we even try to build a single piece,” he says. “But because the process is very three-dimensional, my designs have a sculptural and spatial feel. I think they would turn out very differently if I only worked on a computer or on paper.” It takes roughly eight months to a year to develop a new product, although it can take longer; the aptly named Bloom collection, for instance, took almost three years from concept to final prototype, partly because the search for materials that behaved exactly the way the designer wanted them to was exhaustive. “It takes a lot of teamwork for a single piece of furniture to unfold, from conceptualization to production. I’m not able to build any of my designs by myself. It would be impossible and, frankly, frightening if a single person could build my designs,” Cobonpue says. “That would put me out of business.”

The Voyage bed is constructed of abaca for indoor use and polyethylene for the outdoor version.

Long ago, Cobonpue learned the lessons of his mother, a model from which he has both expanded and deviated. She taught him that originality, superb craftsmanship, and following his heart are worth the greatest of risks. Cobonpue once said that “ideas are infinite”—a person, a brand, even a design is a story told over and over again in many different ways. He asks himself time and again, why must it exist? To be different.

Cobonpue recalls that when he was little, playing in the lush garden workshop of his mother, he built many things, things that rolled and things that crawled and things that flew, and always his mother was there, urging him to imagine something different. “That is very nice,” she’d say when Cobonpue brought her something copied from a book, “but you can do something different.”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.