Errolson Hugh: The Canadian Designer Behind Berlin-based Apparel Brand Acronym

Edge of style.

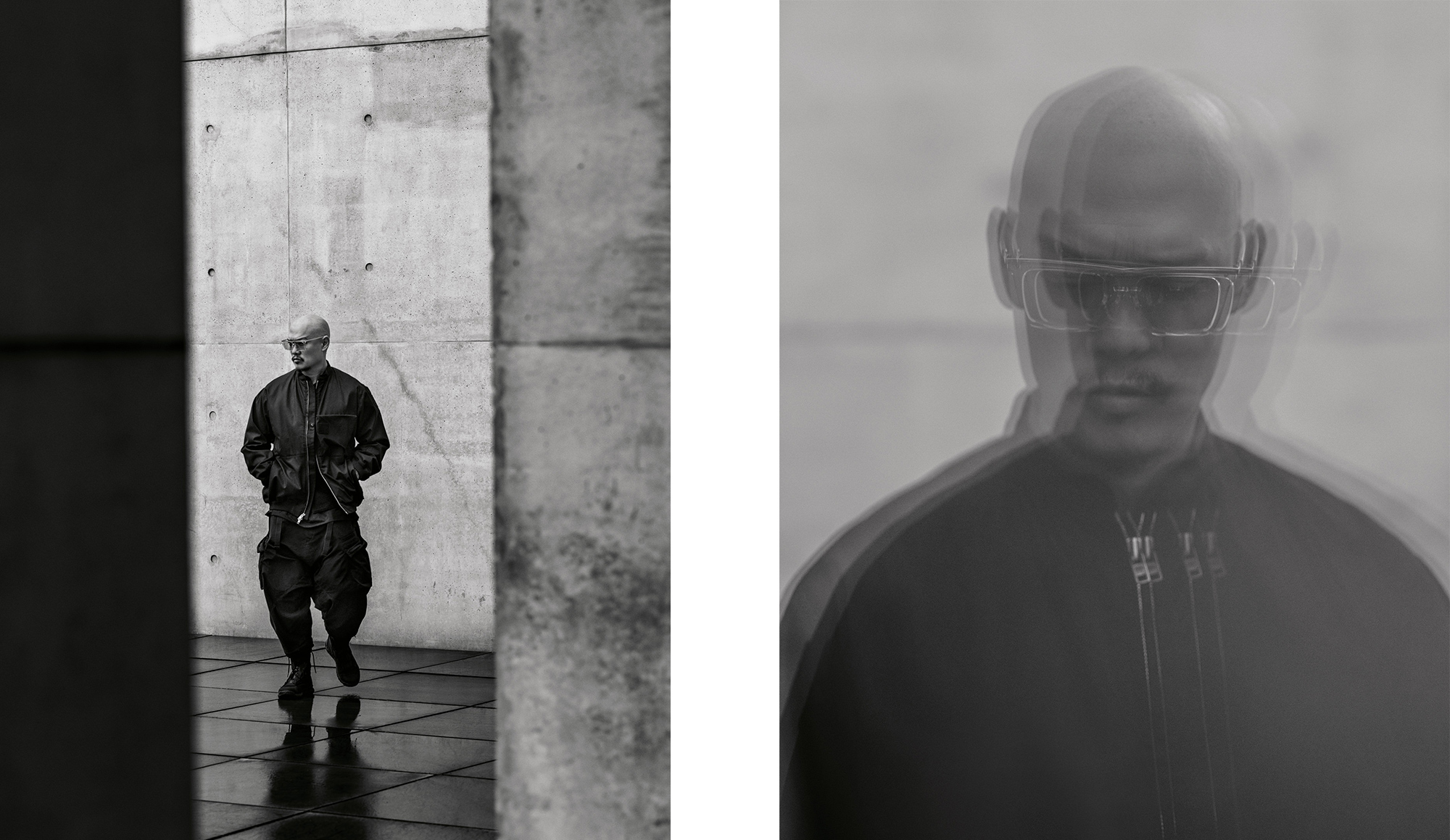

Most of us dress to suit our environs, remaking ourselves in submission to comfort and coherence. Others, like designer Errolson Hugh, trust that their surroundings will accommodate them as they are. Hugh looks more or less the same no matter where you encounter him: wispy goatee, close-shaved head, clothing produced by Acronym, the Berlin-based brand and design consultancy he co-founded in 1994.

Acronym is not a traditional fashion label. It makes what might be the world’s most structurally extreme clothing intended for casual wear. Hugh calls it “inspiration agnostic”, though it leans mostly on cuts and configurations developed for the military or the martial arts. Acronym’s clothing is built for function in the same way as a five-figure hi-fi system—greatly exceeding the requirements of an average user, yet obviously impressive even to those lacking the vocabulary to explain exactly why. Its fabrics repel water and wind, and much of its output works together seamlessly, one grand collection made modular through a suite of design features that recur and interlock. It’s dark and moody, technical and tactical, giving its wearer the air of a black-ops bike courier—words like cyberpunk and dystopian come up often as descriptors. All of which is at odds with the vibe of the upscale West Hollywood hotel where Hugh and I meet. The terrace where we settle, just off an over-scented lobby, is a lush, anodyne non-place.

Hugh arrives with his jacket slung across his back, using an internal rigging system standard on Acronym outerwear. He is in Los Angeles for both business and pleasure. After our meeting, he’ll link up with collaborators on a new, technology-based project, due out mid-2020, that is, he says, unlike anything Acronym has attempted. Earlier in the week, he zipped over to Portland for meetings with Nike—evidence of which rests, in prototype form, in his hotel room—and, before that, hopped a ride to Vegas on friend and diehard patron John Mayer’s jet to catch UFC 245, where another Acronym devotee, featherweight fighter Max Holloway, was on the card. This is a typically peripatetic week.

For 25 years, Hugh has been carving out a niche that is part fashion, part industrial design, and a little bit consumer electronics. To understand why Acronym does what it does, it helps to consider the Walkman. The first portable, personal audio playback device to hit the mass market, it fundamentally changed the way our world looks and feels. Suddenly, our lives had soundtracks, and, for the first time, a piece of technology became an accessory important for both its form and function, like a handbag.

“That portable audio playback—that was the smartphone for us,” says Hugh. “This is my portal into my personal universe. Press play and you’re not there. And, in that way, you’re in control of your environment. We have the same impulse when we’re making outerwear.” That impulse still animates Hugh’s work. “In terms of how we approach the product and what we’re trying to make, nothing’s changed,” he tells me. “It’s identical. But the whole market, the world around it, has completely shifted. When we started, nobody wanted to hear from us. It was too complicated, too difficult, too expensive.”

Today, Acronym is one of the fashion industry’s most influential outsiders. Its collections—only about a dozen pieces, released twice yearly—sell out quickly, and tend to hold value or even appreciate on the secondary market. The brand also has long-standing collaborative relationships with Nike and Stone Island—whose founder, the late Massimo Osti, is the closest thing Hugh has to a fashion forebear—and maintains a steady stream of unpredictable one-off gigs. For instance, Acronym contributed costuming to last year’s Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, and loaned Hugh’s likeness to video game auteur Hideo Kojima for his latest opus, Death Stranding.

“We’re still outside the industry,” says Hugh. “But there’s definitely a recognition, I guess, that we’re not crazy.”

Hugh is comfortable being on the outside. He was born in Edmonton in 1971 to Chinese Jamaican parents, immigrants to Canada. His father is an architect, his mother an interior designer. He grew up on the Prairies before moving to Toronto in 1989 to study fashion design at Ryerson. He hated the city—the structure of his studies—and left soon after graduating to Munich, the hometown of Michaela Sachenbacher, Acronym’s co-founder (and Hugh’s former girlfriend). At the time, Hugh spoke no German. In 1994, he and Sachenbacher began consulting as Acronym, honing their craft with snowboarding brands like Burton before landing in Berlin. In 2002, Acronym began releasing product under its own name, dead set on blending the performance of outdoor gear with an aesthetic to suit a city dweller—dark and largely logoless. Acronym’s elaborate debut was called Kit-1, consisting of a jacket, a messenger bag, a soundtrack, and more. It was sold as a package—a comprehensive introduction to the world of Acronym.

“We want to learn something new, and the best way to learn something is to actually try it on the market,” says Hugh. “From the very beginning, the first kit, people were like, ‘Oh, it’s a concept car.’ ” The implication was that Acronym was creating design fiction, imaginative exercises never intended for actual use.

“But it wasn’t a theoretical idea,” Hugh continues. “It pushed the limits of technically achievable right to the edge, but it did come out of the factory, and it is a real thing. There are hundreds of them. It is very rare to have an environment where the mandate is to push the aesthetics and push the functionality as far as they will go, and actually put it on the market. That’s pretty much all we do, which is why we end up with these ridiculous things like 1,400 euro cargo pants.”

That price tag is no exaggeration. The gear is not cheap, but it’s not overpriced either. Acronym is a lean operation, employing around a dozen people and spending nothing on marketing. It runs its own factory in the Czech Republic, with 60 workers focused exclusively on its collections. Acronym’s products are the output of countless hours of research and development, rendered in specialized fabrics, and produced in minuscule runs. As Hugh might put it, the cargo pants cost what the cargo pants cost.

Though few labels have the luxury of Acronym’s environment, it’s not as though Hugh and his team stumbled into it by accident—it took time, effort, and faith to find their audience. Early support from important retailers such as the now-defunct Colette helped, and Acronym’s work with Nike over the past five years has given its profile a significant boost—Hugh finds himself posing for a lot more selfies and signing a lot more sneakers today than he did a decade ago—but it is fundamentally the clarity and consistency of the label’s vision, articulated in its garments, that has done the heavy lifting. “We just let the work do its thing over time,” Hugh says. “I think we’ve won people over almost jacket by jacket. It’s a different thing, and when you understand, and you decide, ‘I get it, this is for me,’ then you’ll never go back. You’ll never go to something else.”

Hugh tells me about some tweaks they’ve made to a jacket model first introduced in 2011. “For this new version, we spent three months changing the way the pocket opens, and the shape of the pocket bag, and on a bunch of these little, invisible details that changed the practical usage of the item, in our opinion, for the better. But if you look at that first and you look at the one now, they look almost identical.” I’ve heard people in the fashion industry complain that the work looks too similar season to season, which misses the point. Acronym’s output is like a really good, long-running serialized space opera: the structure is consistent episode to episode, but the execution is beyond reproach. If you like it, you probably like it a lot.

Beyond the devoted customers, the marketplace itself bears evidence of Acronym’s influence and prescience. Other labels have since grown into the space it opened. Outdoor performance brand Arc’teryx’s fashion-forward sub-label Veilance might be the best example, and Hugh was a consultant on the project during its inception. Even some mass market brands are catching on to similar ideas—many of Uniqlo’s most popular products, such as its Heattech and Airism lines of innerwear, or its Blocktech parkas, are marketed as technology as much as clothing. Hugh attributes consumer fixation on function to a cultural shift kicked into gear by the rise of the smartphone.

“I think what changed is people expect the things they buy to do things for them,” he says. “Now you’re spending money on technological things that are representative of who you are. It’s not just jewellery or a handbag—your phone and your laptop say just as much about you. And those things are performance items—they enable you to do certain things. So, that mindset has shifted.”

The other design trend Acronym predicted is consolidation, also neatly represented by the smartphone. I might once have packed a camera, a map, a notebook, and a novel for a day trip—today, that’s all covered by a pocket-sized device I have on me regardless. Similarly, an Acronym garment meets as many needs as possible, weatherproof and capaciously pocketed.

What’s interesting, and a little counterintuitive, about Acronym’s appeal is that, just as few of us really deploy the full computing power of a brand new iPhone, the average Acronym wearer will probably never push their jacket to its performance limits. The appeal is less about what wearers are actually doing in the clothes and more about what the clothes make them feel capable of doing. Do I really need to be cloaked in a triple-layered Gore-Tex shell to spend a day walking around Tokyo? No, but it feels a hell of a lot cooler than carrying an umbrella.

“We look at clothing as an interface to your environment,” Hugh says. “The most important one because it’s your identity. But it shouldn’t just be aesthetic. The physics of it should allow you to do things you can’t do when you’re not wearing it. Our whole practice the entire time has been about exploring that idea. That control—you, an autonomous being, in an environment that is potentially hostile, definitely changing, giving you as much agency as possible. That’s the whole idea behind Acronym.”

Here, Hugh sounds like Yohji Yamamoto explaining how he wants the women wearing his clothing to feel powerful, strong, and safe. By pushing function to its extreme, Acronym creates an emotional response in those tuned to its frequency. This is the part often left out of the discussion around Acronym, and the way in which it most resembles a traditional fashion brand, sparking desire by creating an unquantifiable aura. These are clothes that stimulate the imagination, that the wearer can pour themselves into, can dream on, that take on narrative and transmit it in equal measures. For most Acronym devotees, the difference between want and need is irrelevant.

“People will email us like, ‘You’ve gotta help me—my favourite jacket finally gave out,’ ” Hugh tells me. “We’ll get a jacket and see that this guy has his keys in his right pocket every day, this guy wears his shoulder straps on the left side. People wear these things every single day. They don’t feel balanced without them. Then you know you’ve done something good—it’s part of that person’s life, and it has way more history and narrative than we could ever give it artificially. This stuff comes pristine and you destroy it. That’s the idea.”

I had woken up the morning I met Hugh blocks away from the Bradbury Building. A Renaissance Revival–style building plunked in downtown L.A., it was one of the locations used to film Blade Runner—set, fittingly, in Los Angeles, 2019. The 1982 film depicted a grimy, saturnine, neo-noir future of flying cars and rogue automatons. It is very Acronym. I ask Hugh if he can recall whether he imagined what the future would be like when he was a child, and he explains the surreality of growing up during the Cold War. “You’d go down to the gym and have the assembly where they’d show the movie where it’s 28 minutes after they pushed the button. We’ve all got to be in the bunkers, and then there’s nuclear winter. And then you go outside, and it’s recess, and it’s sunny. It’s this weird double life that you had.”

And here Hugh and I are, in what feels like paradise. Clear sky, soft breeze, sparkling water, baby kale salads topped with yuzu and crab on the way. Of course, if you read the news, you know that could all change. So you stay as ready as you can—you keep designing better pockets.

Errolson Hugh wears Acronym throughout.

Errolson Hugh wears Acronym throughout.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.