-

Couture craftsman Joseph Walsh. Photo by Clément Pascal.

-

Magnus Celestii, Joseph Walsh’s largest piece to date, is a sculptural desk with a 25-metre-long wood component that spirals upward.

-

The Enignum canopy bed by Joseph Walsh.

-

Joseph Walsh’s Erosion lll dining table and Enignum IV Copper Chair.

-

Joseph Walsh’s Enignum Lounge Chair.

-

The Lumenoria II Dining Table by Joseph Walsh.

-

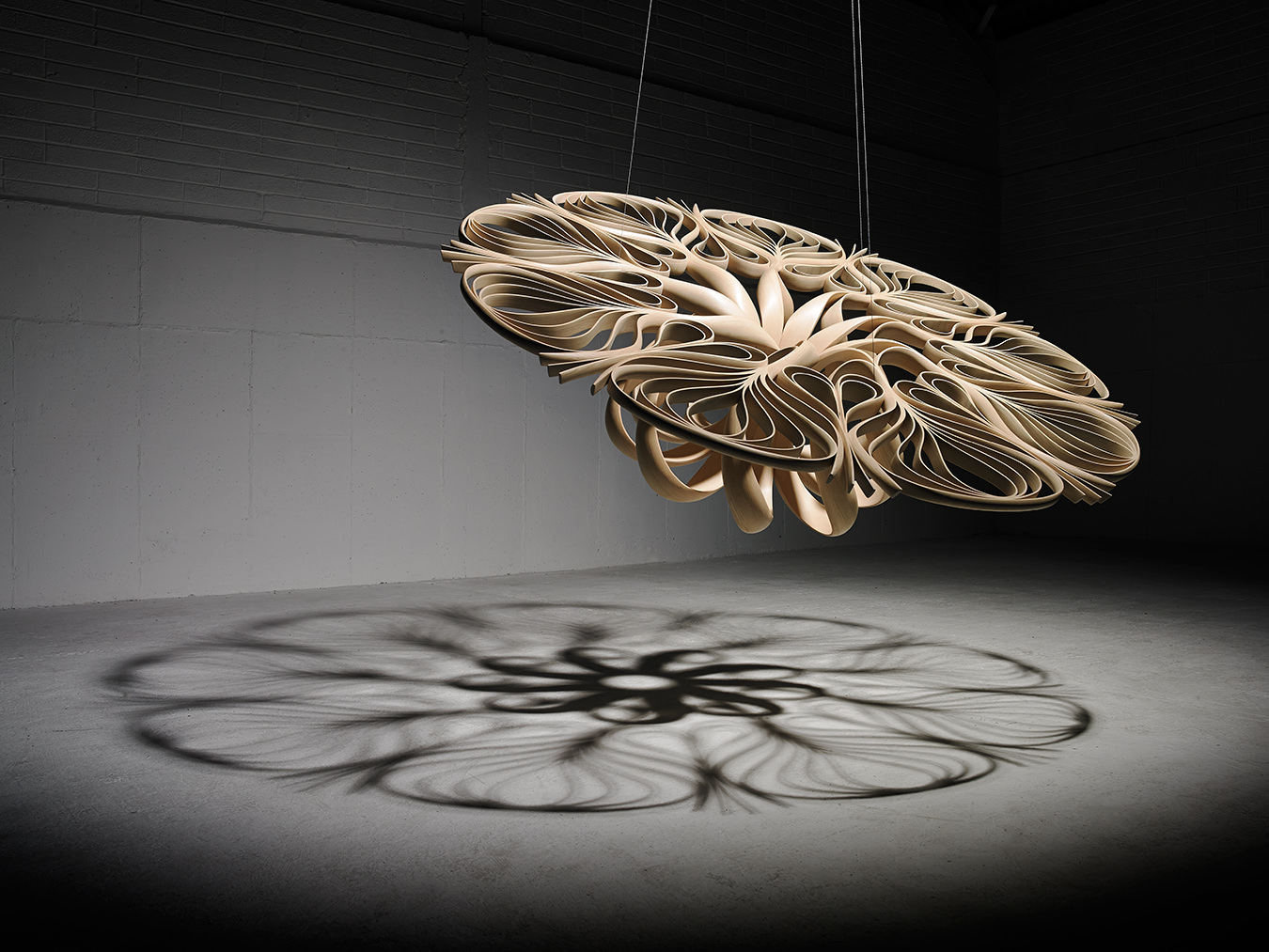

The Lilium II by Joseph Walsh.

-

Joseph Walsh’s Equinox Wall.

Joseph Walsh

A couture craftsman.

By the age of 30, Joseph Walsh was a master craftsman. At the age of eight, he was already busy with fretwork, at 12, copying furniture by sight, and, at 15, accepting commissions. By 19, he had opened his own studio in County Cork, nearly 10 kilometres from where he grew up on the Irish coast and where a carved placard outside his workshop reads: Joseph Walsh Bespoke. Walsh calls himself a designer-maker and maintains a reciprocity between the studio (where ideas are born) and the workshop (where they are tested) that has made his work a constant improvisation. He is also a paradigm of the increasingly emphatic reconciliation of craft, art, and modern design.

In the past several years, Walsh has polished his techniques and clarified his sensibility, making one-offs and limited-edition furniture and art installations from (primarily) wood that appear impossibly fluid. His staff has more than doubled in that time, from six to 15, while his work has been commissioned for embassies, churches, and hotels, and collected by the Museum of Arts and Design in New York and the National Museum of Ireland, by Uruguayan architect Rafael Viñoly, and by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire (who requested a site-specific bed that now stands more than six metres high). The Mint Museum of Craft & Design in North Carolina commissioned his 2010 Enignum Motion console table with storage, which converts into a desk via articulated slats that can be lifted on their hinges to form a cobra’s hood over the work surface. This past winter, he was working on large-scale sculptural shelving for a 15th-century Italian church near Verona.

Walsh’s functional sculpture—his furniture—is “timeless” in the sense that it is suited to every era and none at all: each piece unfurls with the romanticism of a nameless past while having a clarity and a naked discipline that is wholly modern. Today, at the age of 35, Walsh has become a significant innovator at the intersection of the classic and the progressive. He is a couture craftsman who is changing the shape of his craft.

Walsh was born into a large family in 1979, and raised on a farm, where making was joyfully taken for granted. “My mother was constantly creating. She would make her own clothes, keep a kitchen garden, bake, make jams and tapestries—it was all in a day’s work. This culture allowed us to imagine and make without hesitation,” says Walsh, who has the hands of a piano player instead of a farmer and, when his hair isn’t cropped short, an irrepressible curl that falls over his forehead.

As a boy, Walsh cut figures from plywood with a fretsaw. He made cabinets, tables, and a farmhouse kitchen dresser, and then pieces to order, the first being a bay window seat, then a dining room sideboard and cabinets followed by a library. Walsh is entirely self-taught. Illness kept him out of school for a few years in his early teens, and he opted to set up his studio instead of attending university. He may have read “the obvious woodworking books,” he says, visited makers and museums in England, and picked the brain of a local boat builder, but mostly he learned by doing.

Ambitious is a word that even Walsh has used for his work. His laminated and bent wood pieces are viscous and liquid and visually featherweight. Their creation involves a give and take between discovering forms in his materials and generating his own forms in tandem with them. Walsh loves wood for its very nature, but then manipulates it in a way that Nature cannot: the process requires patient domination of the material (a single table can take nine months) and, simultaneously, a collaboration with it. “Maybe it is like dance,” he says. “You have an idea for a piece, a sequence, a movement, a form, but then you have to work with the performers to get the most out of them. You might have to evolve your original idea to suit their characters but, in doing so, achieve much more. This is what we are trying to achieve by working with natural materials. The material speaks in the final work, but in a way you have never seen before.”

These days, Walsh has brought makers into the studio from places as varied as Argentina, Finland, and Western Europe, from the Shinrin Takumi Juku in Japan and local upholstery workshops and sculpture ateliers to the Netherlands’ wholly progressive Design Academy Eindhoven. Even though each person is highly skilled, Walsh developed an in-house training program to establish a common workshop “making language”.

Walsh first exhibited in London in 2002, and, by 2007, had been picked up by Milan’s Nilufar gallery. (It was Nilufar—which would exhibit his work in a 16th-century Milanese palazzo at the Salone Internazionale del Mobile six years later—that made it clear just how thoroughly modern Walsh’s work really is.) Even before that, Irish design and craft curator Brian Kennedy noticed Walsh’s thickly italicized Suaimhneas rocking chair in 2004. “Its sheer elegant simplicity married to technical virtuosity really struck me,” he says, “and I immediately knew that this was a designer to follow.” Walsh emerged before the powerful Celtic Tiger economy went bust, while the Irish cultural scene was still flush with money and confidence. Irish architecture was taking big leaps forward, Kennedy recalls, and it was in this flourishing creative moment that Walsh established his studio and responded to the ambitious nature of Irish architecture with equally ambitious furniture. Kennedy went on to show Suaimhneas at the Sculpture, Objects, and Functional Art exposition (SOFA) in Chicago in 2007, where its iconic image was used to promote the show on ad banners along Michigan Avenue.

In Walsh’s early work, there were explicit seams, wood slats smoothed together, materials mixed and matched—olive ash, oak, burr elm—different tones of blond wood forming stripe-y patterns over sinuous forms. The shapes, patterns, and textures seemed incongruous at times; the lithe forms that he would perfect later on were still slightly chunky (his 2004 Figure of 6 chair anticipated the relentless fluidity of the Enignum chairs five years later). Construction was privileged over expression, carpentry over art. The 2006 Collector’s Cabinet is a cylindrical wooden hinge resting at a tilt on an industrial steel stump. The forms were elastic and sculptural, the compositions daring in their asymmetry, but the ideas were splinters—fractured and unfocused—like texts heavy with too many adjectives.

In 2008, Walsh had a major show in New York at the American Irish Historical Society. It was widely praised, but he felt suddenly disappointed with all of it. Walsh recalls having a conversation around that time with the American textile designer and promoter of contemporary crafts Jack Lenor Larsen, who wrote to Walsh praising his work. “But he suggested that I had not yet found what I was searching for as a designer. He suggested that even a blind man should be able to appreciate sitting in one of my chairs, and encouraged me to look at the delicacy of bird bones,” Walsh remembers. “That was a turning point.”

Walsh’s furniture is “timeless” in the sense that it is suited to every era and none at all. Pieces unfurl with the romanticism of a nameless past.

At that point, Walsh had begun to untether himself from cabinet making, per se, and to establish his own art, systems, and techniques. The titles of his pieces began to signal that the work had found its roots in prolonged studies of abstract natural concepts. Erosion was the inspiration for the Formations series: he carved away parts of slatted screens so that walking past the piece makes its whole topography seem to shift. He defined the form of a coiled bench and tabletop by its voids. From 2009 on, titles were usually a Latin-sounding compound—Enignum, Equinox, Exilumen—like a botanist’s categorization by genus and species, suggesting a tribute to Nature, which inspired them, and to the human capacity to assert them.

And so, ironically, the work, having found its focus in the natural world, became otherworldly. Quirky dissolved and resolved itself into a purity of form. The material palette became more sophisticated as he simplified it. His pieces were no longer disconnected formal and material experiments, and suddenly they didn’t feel constructed at all. They became investigations into ideas as much as things: Equinox is an exploration of layers in the natural world, the cambium layer and the rings of trees, the way in which these layers have measured and recorded time and how time has, in turn, shaped them.

In the Enignum I series of wooden chairs, canopy beds, sofas, and shelving that resemble pulled taffy and have the delicacy of, yes, bird’s bones, Walsh stripped wood into thin layers and then manipulated these layers into free-form compositions. The title Enignum refers to the “enigma” of the form, which is informed by the material properties of the “lignum”, the tree’s woody flesh. The shelf seems to issue, like sap, from the wall. The Enignum chairs shed their weight and their edges. He crafted the Enignum pieces in ash, the colour, weight, and texture in keeping with his goal to focus on the expressive sculptural intention rather than to play with detail, colour, or tones. “When I started the Enignum series, I really wanted to create pieces that were an expression for me, with an energy that represented me,” Walsh says. “I wanted a material honesty, a purity whereby there was no decoration or application, just something pure and raw.” The Enignum V and VI canopy beds, made in 2013, are deeply romantic objects that, by contradicting Walsh’s conspicuous reserve, suggest that something else may lie beneath the public face of the maker and that Walsh may have achieved his goal in a powerful way.

Though much of his career has involved laminating wood to wood, hand-shaping, sculpting, and carving it, the apotheosis of this language can be seen in Enignum and in his largest piece to date, the Magnus Celestii—a sculptural desk with a 25-metre-long wood component that spirals upward and outward—which was installed (from May to October of last year) in the New Art Centre, an art gallery and sculpture park located in a 19th-century English house in Salisbury, U.K. It generated a gentle maelstrom as it streamed around the perimeter of the room, ascending to the ceiling, while being anchored humbly at its foot by a simple desktop and shelf, making it a scaled-up evolution of the Enignum XIII shelves. But whereas the Enignum chairs used 20 square metres of wood, Magnus Celestii used 700, making the piece lightly immersive: “I wanted to bring the user inside the Enignum forms and yet retain a purposeful function,” Walsh explains, “so the user could live within this dreamy sculptural object that then becomes a part of the user’s reality”—a transporting experience that becomes part of the every day.

Three years in the making, Lumenoria and Exilumen, shown in November 2014 at New York’s The Salon: Art + Design, are a picture of the fully matured studio vernacular being rendered only partly in wood—Lumenoria tables consist of amber resin poured over sculpted wooden bases—and then, withExilumen I, in entirely different materials altogether. Walsh was drawn to Irish green marble, but he didn’t want to just carve into it. The resulting piece generates a certain amount of tension because it appears to float a massive slab of Irish green marble over nothing.

Craft demands an emotional and manual intelligence of the highest order. That is the essence of what is expressed through the maker’s hands and the quality to which viewers and consumers immediately respond. Walsh has this intelligence in spades, and it makes the experience of his work as emotional as it is visual, as much about spirit as it is about (wood) flesh. “The fact that Joseph’s pieces are made rather than manufactured is hugely important to today’s audience,” says Brian Kennedy. “In an era when more and more work is designed digitally and virtually, there is an increased need for people to identify with the maker, the producer, the artist. They want to see the hand within the work and a thinking through the material.”

Product photos provided by Joseph Walsh Studio.